Exhibition Notes

Exhibition Note: Morrison R. Waite and “Great” Supreme Court Justices

ON April 18, 2019

By John E. Noyes

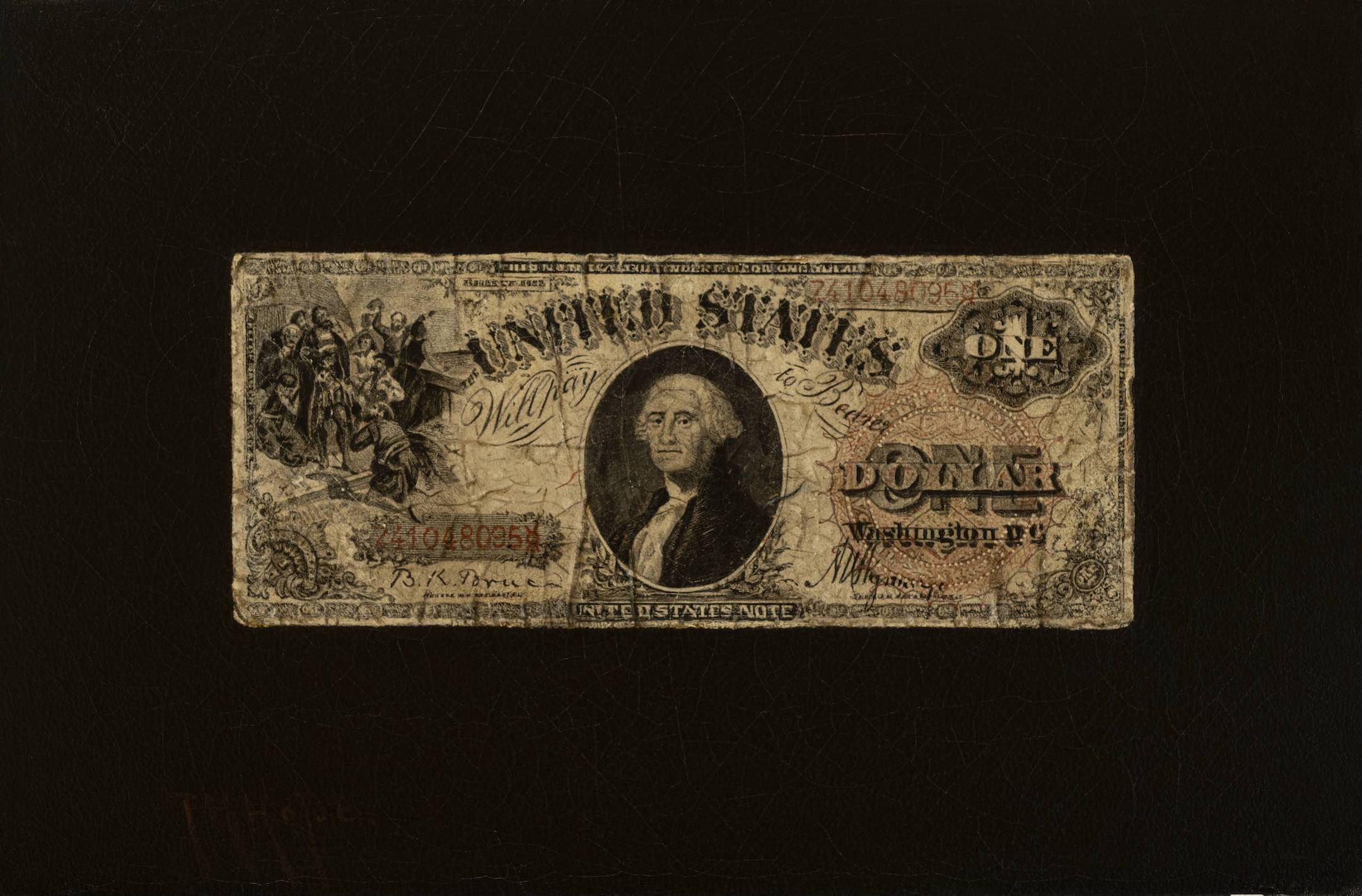

Featured Image: Attributed to Thomas LeClear, Morrison R. Waite. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1876.

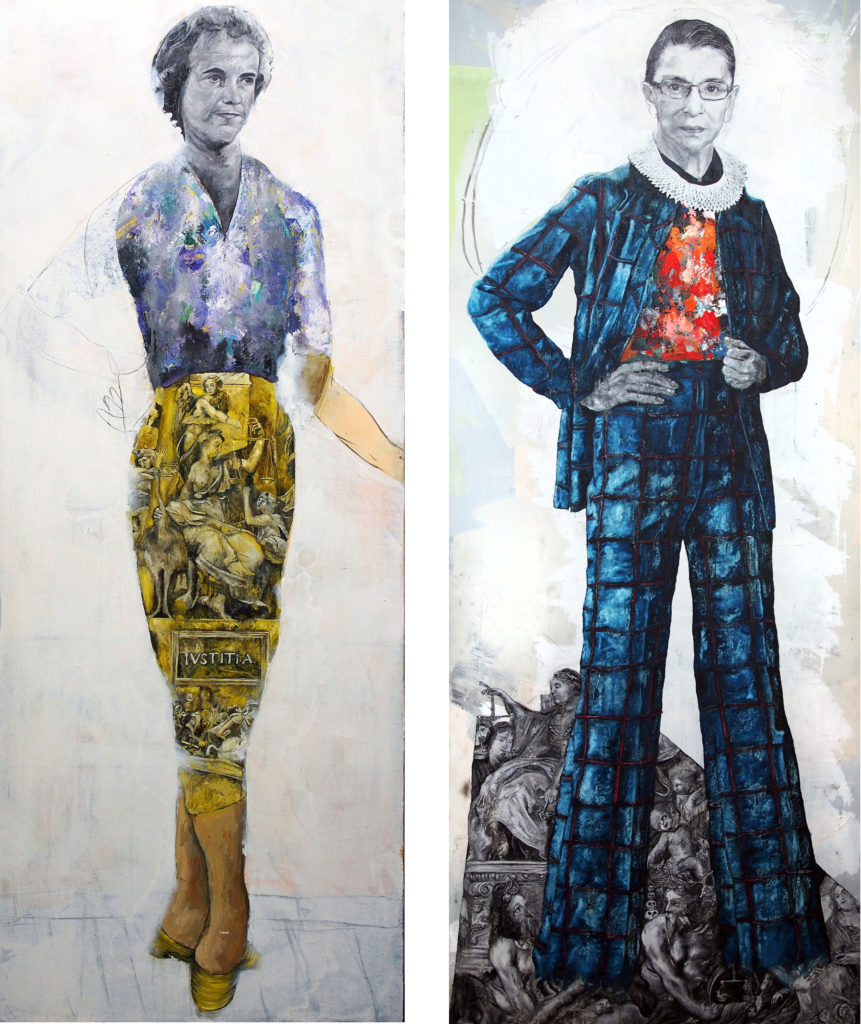

The Great Americans exhibition at the Florence Griswold Museum featuring paintings by Jac Lahav prompts us to think about how historical and social contexts shape our notions of greatness. Lahav’s two portraits of U.S. Supreme Court Justices – Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg – evoke their pioneering work and struggles as women lawyers and jurists. Their compelling life stories, perhaps even more than their contributions to the Court’s jurisprudence, have captured popular and media attention.

[L] Jac Lahav, Sandra Day O’Connor: Justice, 2018. Courtesy of the Artist, [R] Jac Lahav, Ruth Bader Ginsburg: Justice, 2018. Courtesy of the Artist.

Most lawyers and historians would count John Marshall, the nation’s first Supreme Court Chief Justice, as a “great American,” and many would accord the same status to Chief Justice Earl Warren, who led the Court during the 20th century’s civil rights reforms. Both served during turbulent times and shaped constitutional limits on governmental actions.

Few people today have heard of Morrison Remick Waite (1816-1888), Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1874-1888 and a native of Old Lyme. Was he ever considered a “great American”? Do notions of greatness vary from region to region or town to town? Does geographical proximity contribute to perceptions about greatness? In the last quarter of the 19th century, Old Lyme, if not the nation at large, deemed Waite to be great. Town residents claimed Waite as their own, admired his professional accomplishments, and praised his character. Waite’s connections to Lyme and Old Lyme (incorporated as a separate town in 1855) endured throughout his life, even though he spent most of his legal career in Ohio and Washington, DC.

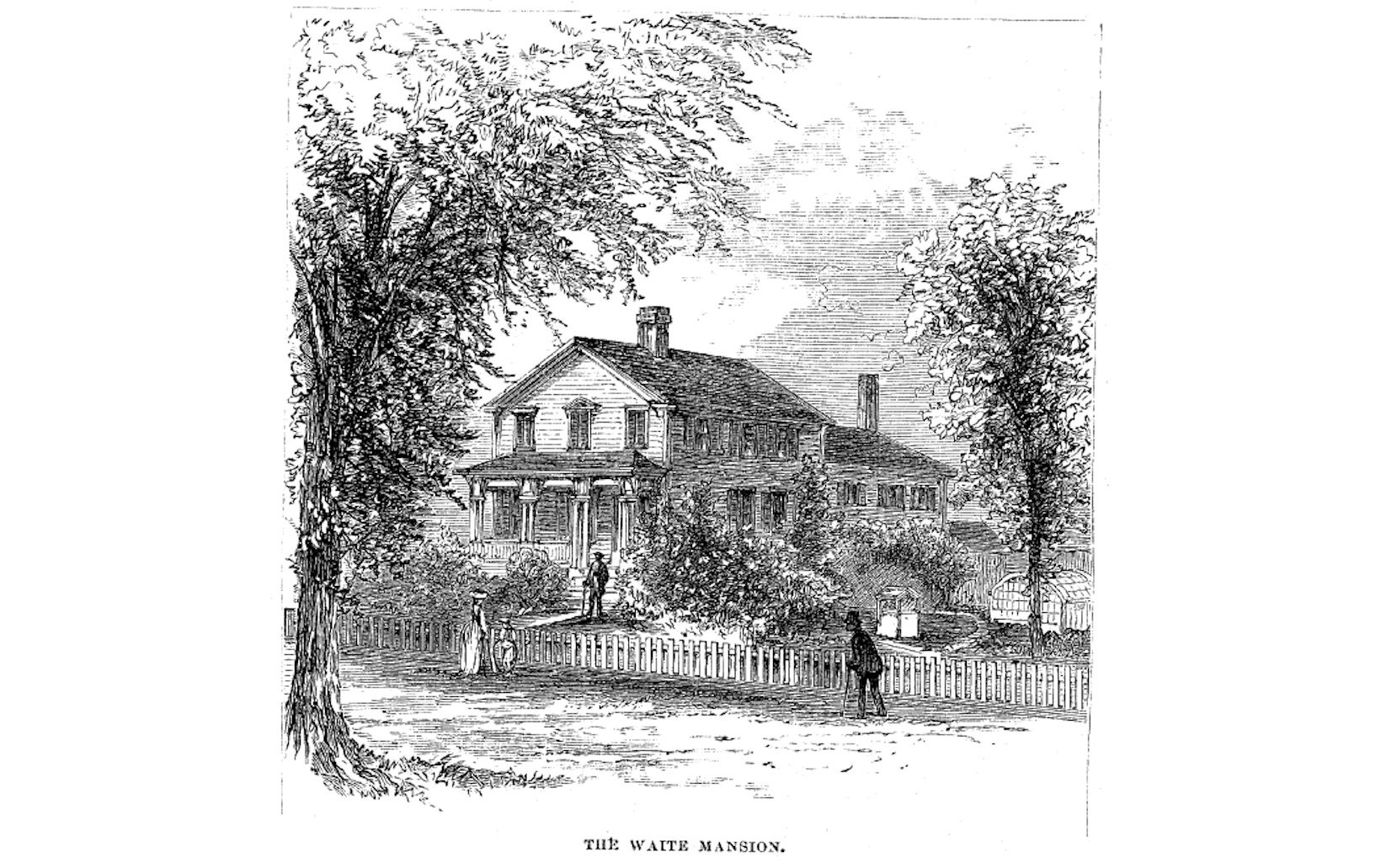

Attributed to Charles Parsons, The Waite Mansion. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1876.

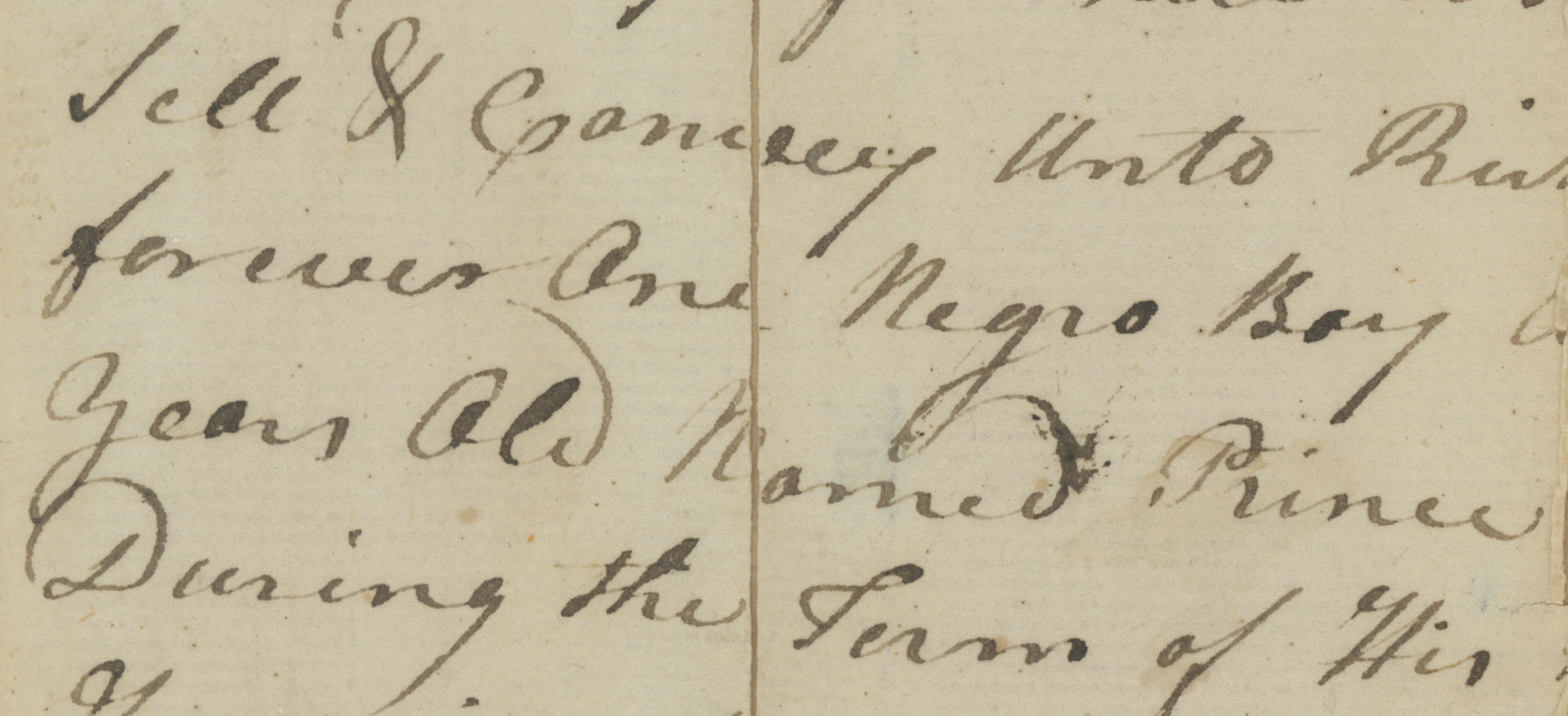

Morrison Waite was born in Lyme on November 29, 1816, the first of eight children of Maria Selden and Henry Matson Waite, who served as Chief Justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court from 1854-1857. Morrison spent much of his boyhood in the Waite home on Lyme Street, situated just north of the present-day Cooley Gallery, a house that today has been rebuilt and moved back from the road. He attended Bacon Academy in Colchester and then Yale, graduating in 1837 and returning to Lyme to study law under the tutelage of his father.[1] In 1838, however, Waite left town to pursue legal opportunities on the Ohio frontier, where an uncle and many Connecticut residents had relocated. Waite nevertheless maintained his Connecticut ties, marrying his second cousin, Amelia C. Warner of Lyme, in 1840[2] and spending summers in Old Lyme during his years as Chief Justice.

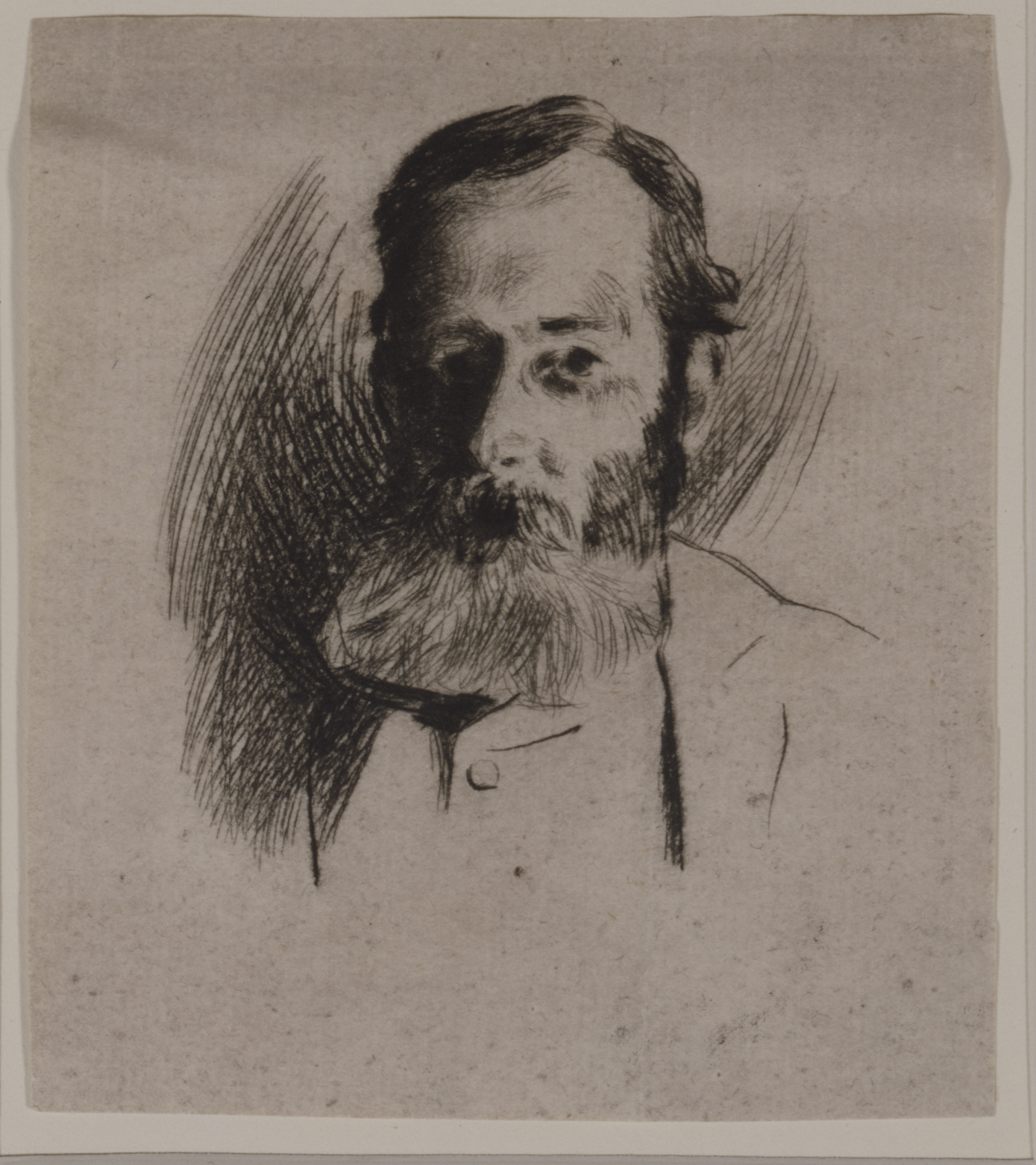

Morrison Waite. Noyes-Ely Collection, Lyme Historical Society Archives

Waite did not seek political fame, devoting most of his career to building a successful commercial law practice in Ohio. He did achieve some public recognition there by serving for a term in the state legislature, working for Whig political causes, and, during 1873-1874, presiding over Ohio’s Constitutional Convention. Waite gained national prominence in 1871 when President Ulysses S. Grant named him one of the three U.S. counselors in the Alabama Claims arbitration in Geneva, Switzerland, which ruled against the United Kingdom for violating neutrality rules during the U.S. Civil War. The U.K. honored the arbitral tribunal’s award, paying the United States the full amount due of $15,500,000 – about five percent of Britain’s annual national budget at the time – and the result energized the popular pro-arbitration movement in the United States. Grant, encouraged by the outcome, foresaw “an epoch when a court recognized by all nations will settle international differences” instead of countries “keeping large standing armies.”[3]

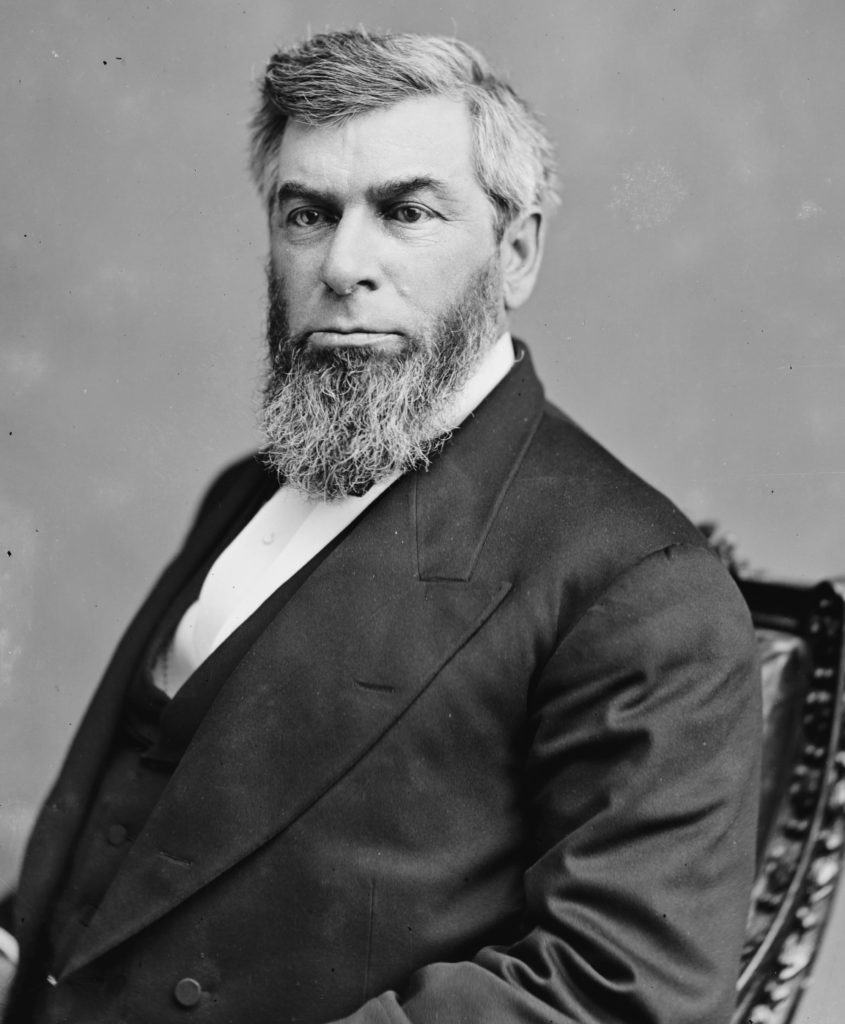

Grant nominated Waite to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court on January 19, 1874, and the Senate approved his appointment two days later by a vote of 63-0. As Chief Justice, Waite balanced long-standing principles of federalism with the mandates of post-Civil War constitutional amendments and civil rights legislation. According to one scholar, Waite’s leadership skills as Chief Justice and his moderate judicial approach during the challenges of Reconstruction and a period of great industrial growth reflected “the work of a judicial statesman in the tradition of other great chief justices such as John Marshall and Earl Warren.”[4]

Matthew Brady, Chief Justice Morrison R. Waite. U.S. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

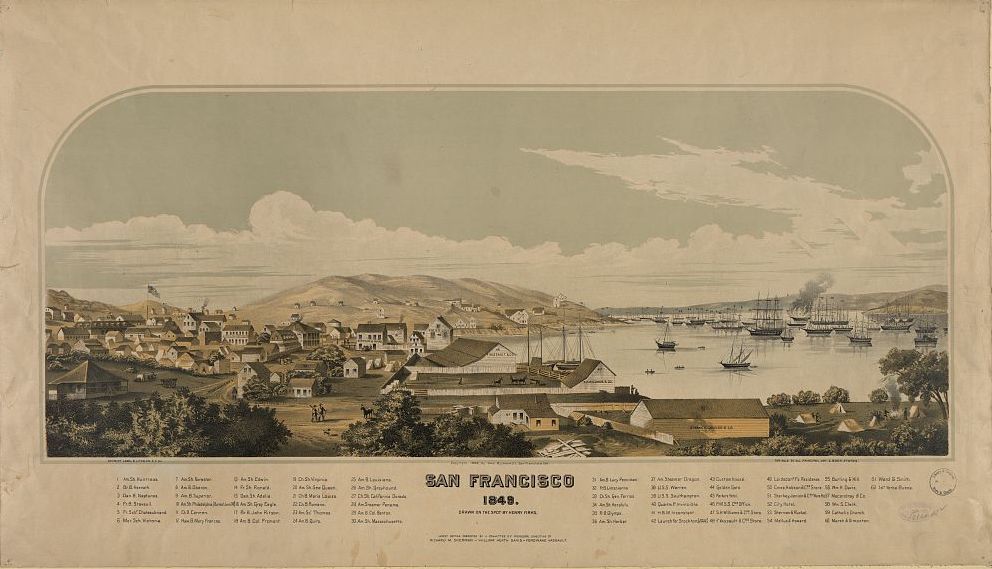

Old Lyme gained in national recognition and stature once Waite became Chief Justice. The historian Martha Lamb introduced her flattering portrait of Old Lyme society in the February 1876 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine by discussing Waite’s elevation to the position of Chief Justice and then devoted several pages of her article to Waite and his family. Newspapers recorded Waite’s summer visits to Old Lyme, where the Chief Justice, along with his wife Amelia and their daughter Mary, stayed at the Noyes-Beckwith House on Lyme Street or, on at least one occasion, at the Pierrepont Hotel on Ferry Road.[5] “Chief Justice Waite and family are settled for the summer at their native place, Lyme, Conn.,” read one newspaper account, “where they have invited ex-President and Mrs. Hayes to join them. If they come they will be entertained at the fine old house of the late Captain Robert H. Griswold, which is opened this summer for boarders.”[6] Although it is unclear whether former President Hayes, in fact, made the trip to Old Lyme or was ever entertained at the Griswold House, it is clear that Waite brought attention to the town.

Pierpont House Hotel, Ferry Road. LHSA

While in Old Lyme, the Chief Justice took part in local events. His social activities included a Salisbury family tea honoring the historian Martha Lamb and a lavish party at the home of John van Bergen, known as Cricket Lawn.[7] Daughter Mary also enjoyed Old Lyme festivities, joining “in the concerts, tableaux, plays, and other entertainments of the young people.”[8] In July 1878 Waite participated in the local Ely family reunion, a major event that drew over 500 people from some 16 states and Canada, though a telegram concerning a matter of “imperative necessity” called him out of town before he could deliver his scheduled reunion address.[9] Waite also attended an 1887 ceremony rededicating the Old Lyme Congregational Church after it had been extensively renovated. Rev. Benjamin Bacon noted Waite’s efforts, probably aided by Amelia, in “ministering to the poor” and extending hospitality “to the needy and the sick.”[10]

Old Lyme honored Waite’s personal qualities. Lamb praised Waite’s “acute sense of justice, strong opinions, sound judgment, and … spotless personal record.”[11] Edward and Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury wrote: “from personal knowledge of his most friendly disposition, his entire freedom from all pretentiousness, his frank cordiality, and his warm interest in the welfare of his birth-place.”[12] Both colleagues and Old Lyme residents noted Waite’s strong work ethic and sense of professional obligation. After he died on March 23, 1888, of pneumonia – likely related to exhaustion from overwork – Rev. Bacon, officiating at a memorial gathering in Old Lyme, emphasized that Waite’s personal qualities and “faithfulness to duty” gave “his career the truest title to greatness.”[13]

Thanks to Cheryl Kozdrey, Amy Kurtz Lansing, and Carolyn Wakeman for their assistance.

[1] C. Peter Magrath’s well-researched biography, Morrison R. Waite: The Triumph of Character (1963), includes some background about Waite’s early years in Lyme and his time at Yale.

[2] Waite’s marriage to Amelia Warner on September 21, 1840, at a ceremony officiated by Frederick Gridley, the pastor of the East Lyme Congregational Church, is recorded at page 176 of Vital Records of Lyme, Connecticut, 1665-1850 (1976).

[3] President Grant’s reaction to the Alabama Claims arbitration is quoted in Mark Weston Janis, America and the Law of Nations, 1776-1939 (2010), p. 134. Janis explores the social, religious, and legal context of the arbitration movement in the United States. For more on the Alabama Claims arbitration and its significance, see Tom Bingham, “The Alabama Claims Arbitration,” International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 54, pp. 1-25.

[4] Robert M. Goldman, “Waite, Morrison Remick,” in Biographical Encyclopedia of the Supreme Court (Melvin I. Urofsky ed., 2006), p. 576. For a more modest appraisal of Waite’s talents as a leader, see D. Grier Stephenson Jr., “The Chief Justice as Leader: The Case of Morrison Remick Waite,” William & Mary Law Review, Vol. 14 (1973), pp. 899-927. For a detailed and nuanced study of the jurisprudence of the Waite Court, see Paul Kens, The Supreme Court under Morrison R. Waite, 1874-1888 (2010).

[5] For the summer residences of the Waite family in Old Lyme, see Old Houses of Connecticut (Bertha Chadwick Trowbridge ed., 1923), p. 114, and “A Pleasant Shore Resort,” Sept. 1887, a news clipping pasted at p. 119 of a bound volume in the Clippings (Scrapbooks) file, Lyme Historical Society Archives [hereafter LHSA Scrapbook].

[6] “At Lyme,” [undated], LHSA Scrapbook, p. 41.

[7] For accounts of Waite’s summer activities and visits to Old Lyme, see Magrath, pp. 307-309, and newspaper clippings in LHSA Scrapbook.

[8] LHSA Scrapbook, p. 91.

[9] For Waite’s involvement with the Ely reunion, see History of the Ely Re-Union Held at Lyme, Conn., July 10th, 1878, pp. 9, 15, 71, 92, and 151.

[10] Quoted in Edward Elbridge Salisbury & Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury, Family-Histories and Genealogies, Vol. 1 (1892), p. 358.

[11] Martha J. Lamb, “Lyme: A Chapter of American Genealogy,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 52 (Feb. 1876), p. 313. Lamb, who knew Waite when he practiced law in Maumee, Ohio, provided additional assessments of his character in “Chief Justice Morrison Remick Waite – His Home in Washington,” Magazine of American History, Vol. 20 (July 1888), pp. 1-16.

[12] Family-Histories and Genealogies, Vol. 1, p. 357.

[13] Quoted in Family-Histories and Genealogies, Vol. 1, p. 358.