by Carolyn Wakeman

Witness Stones alongside the front walkway to the Florence Griswold Museum, a former site of enslavement, commemorate Harry Freeman, Temperance Freeman, and Crusa.

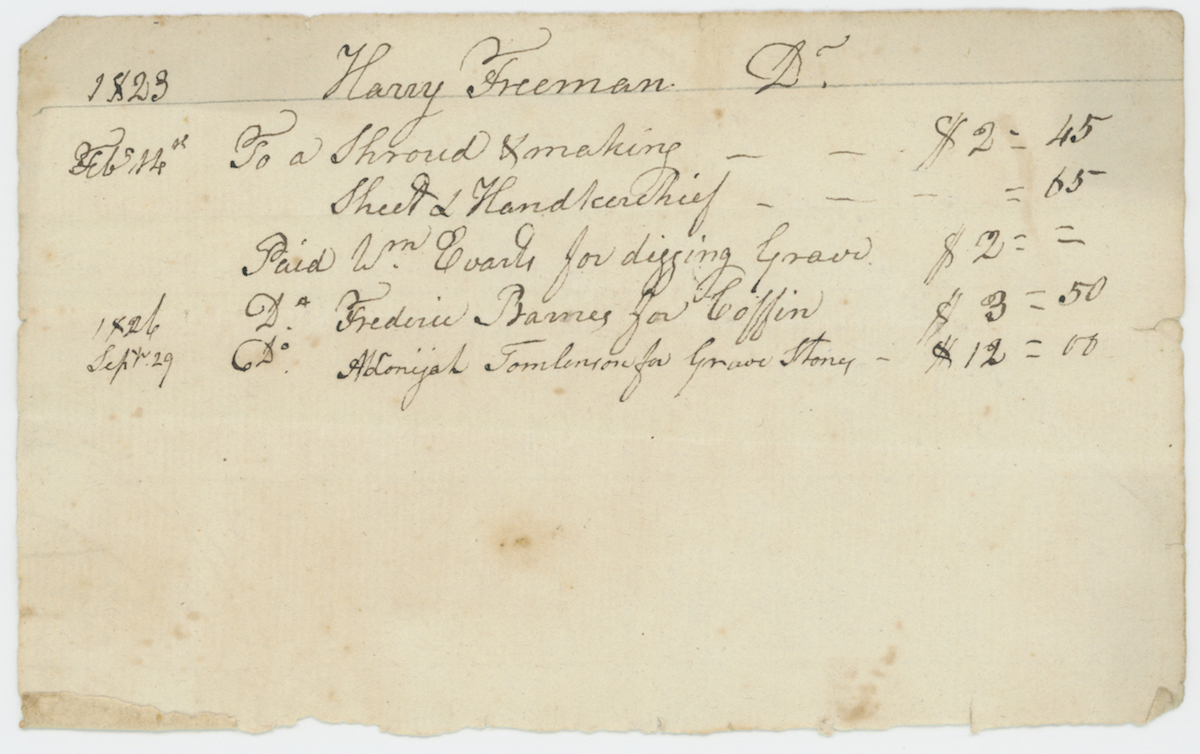

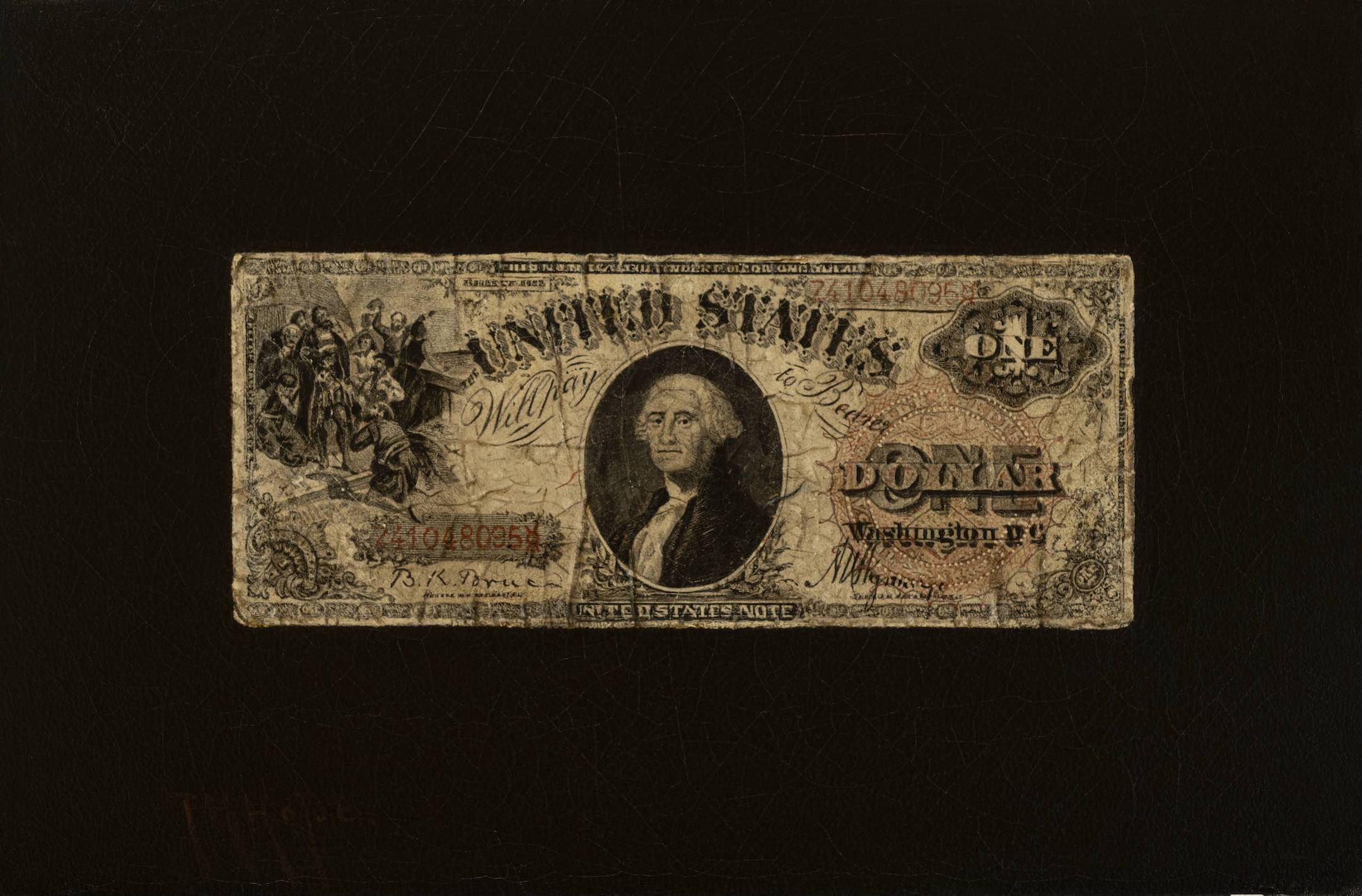

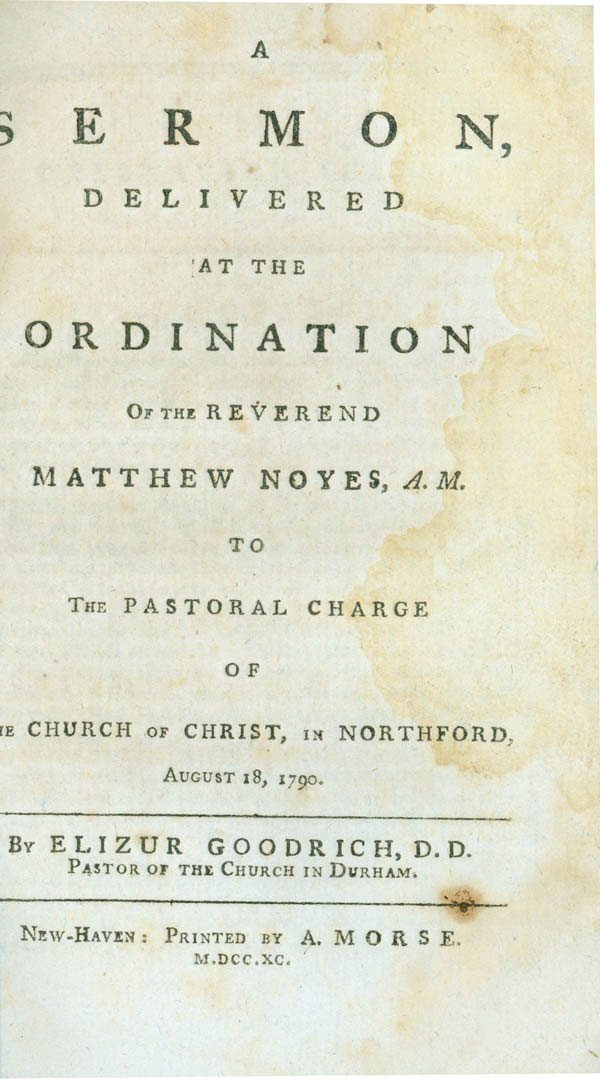

A small sheet of yellowed paper discovered in the archives at the Florence Griswold Museum provides a glimpse of how children born enslaved in Lyme were distributed. The papers of Rev. Matthew Noyes (1764–1839), ordained in 1790 as minister in Northford (today’s North Branford), include a list of burial costs for Harry Freeman. Almost two centuries ago on February 14, 1823, the minister paid $2.45 for “a Shroud & making,” 65 cents for a “sheet & Handkerchief,” and $3.50 for a coffin. Three years later he purchased a gravestone from Adonijah Tomlinson for $12.00.

Henry Freeman burial costs, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

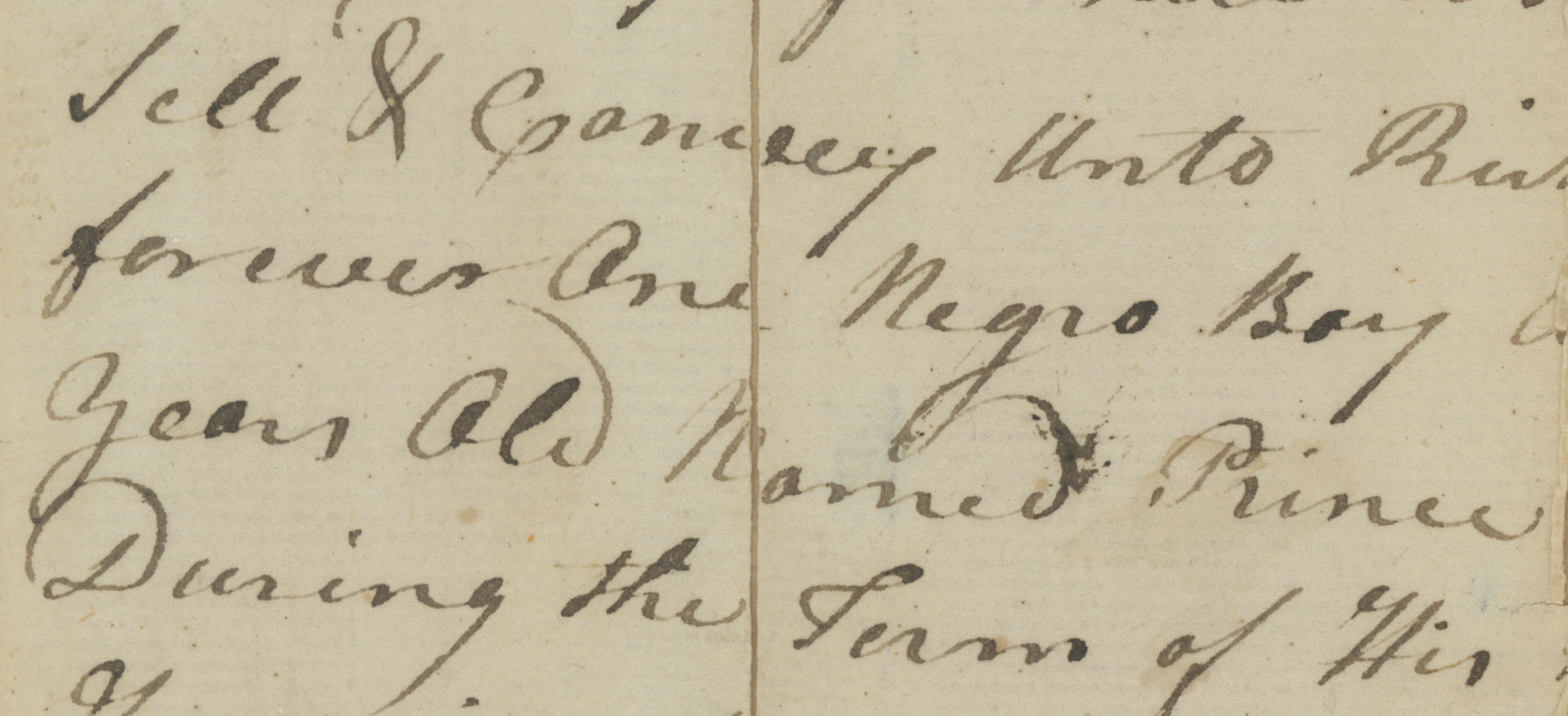

Other documents shed additional light on Harry Freeman’s life. Lyme’s vital records state that on July 23, 1791, William Noyes (1716–1807) personally appeared before justice of the peace Seth Ely to report the birth on December 3, 1790, of “My Negro boy Harry.” A 19th-century scrapbook page listing those whom Judge William Noyes enslaved provides brief notes about Harry and other members of his family. Those entries strongly suggest that he was Nancy’s son; Jordan, Sabina, and Isaac’s brother; Jenny and Prince’s grandson; and Prince, Pompey, Crusa, and Temperance’s nephew.[1]

Noyes family scrapbook, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

Harry’s father was likely Jordan Freeman, for whom Nancy’s oldest son was named. Birth records specify that Nancy and Jordan Freeman had a son Isaac Freeman on May 17, 1812, and a notice that Jordan Freeman posted five years later in the Connecticut Gazette on December 31, 1817, announced Nancy’s departure from his house. The published notice that she had “eloped” from his bed and board ended his obligation to provide his estranged wife with financial support.

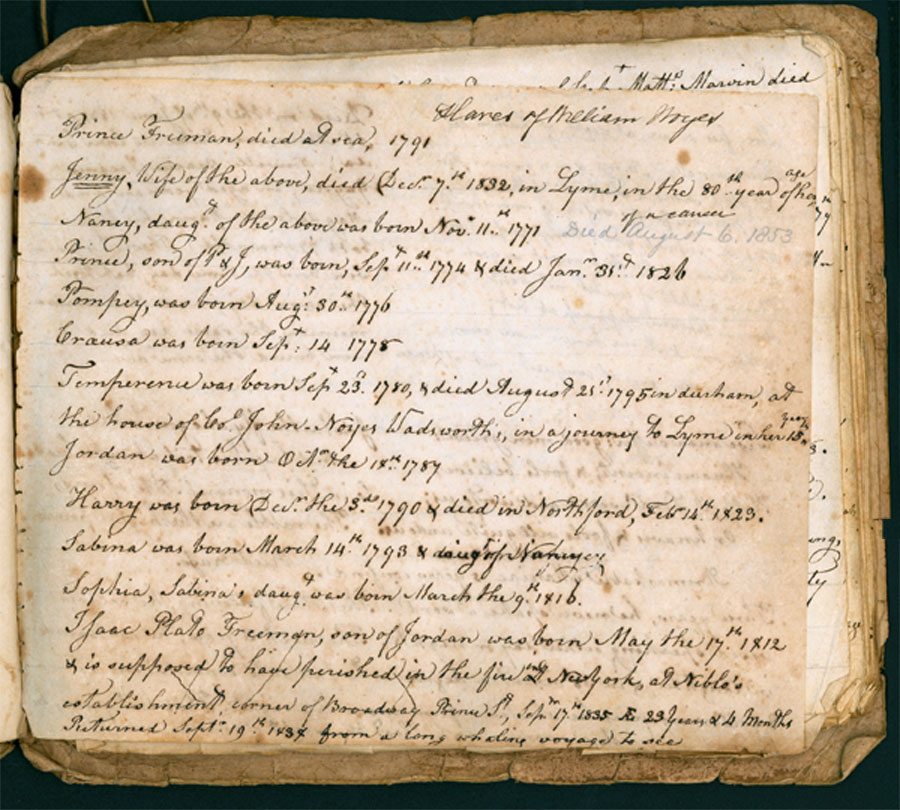

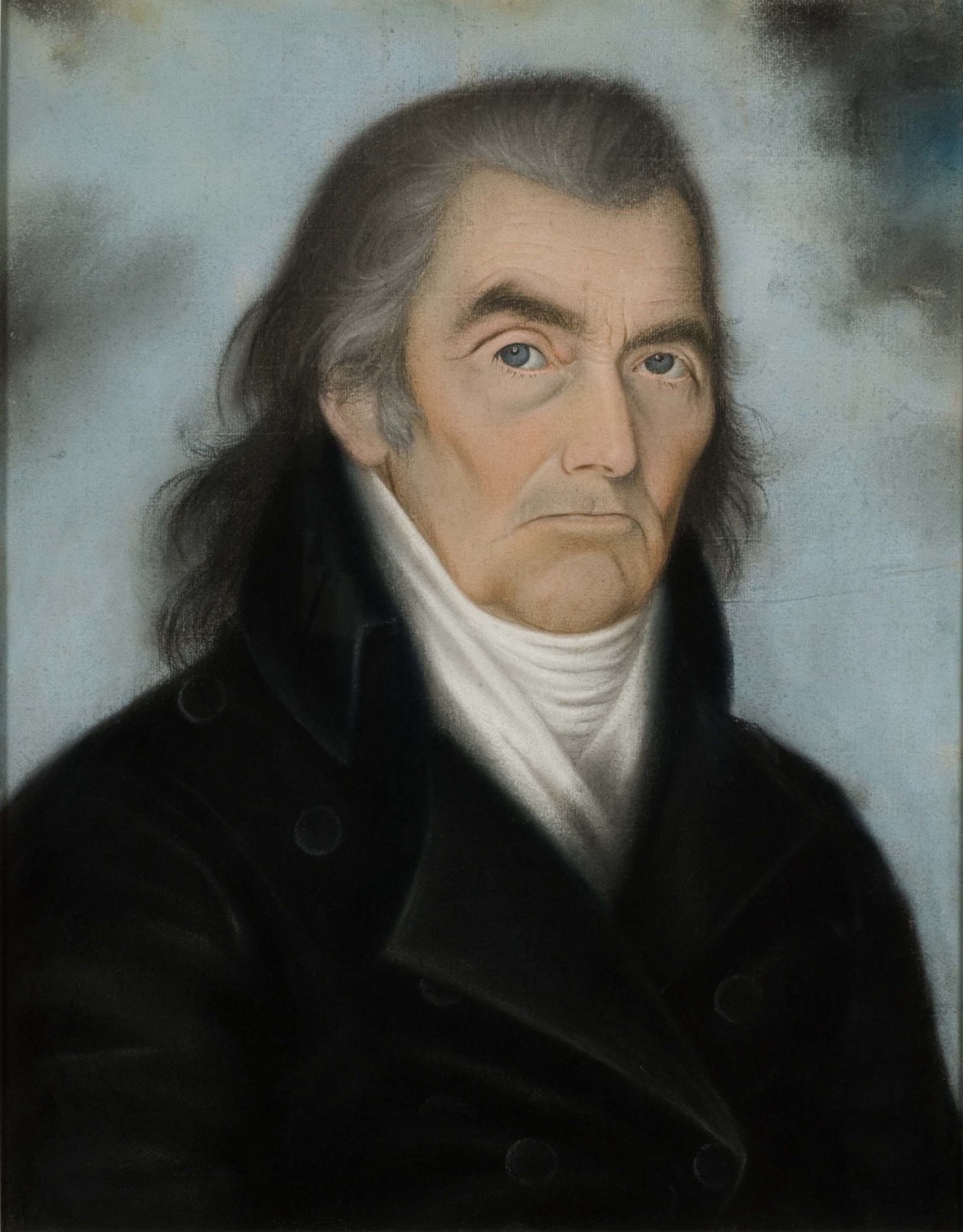

Matthew Noyes had grown up with the African-descended family held in bondage by his father on today’s Lyme Street during the tumultuous years of Revolution. Matthew was seven when Nancy was born into hereditary slavery in 1771, he was a student at Yale when her first son Jordan was born in 1787, and he had been recently ordained in Northford when her second son Harry was born in 1790. A month before Harry’s birth, Rev. Noyes married Mary Ann Johnson, daughter of Lyme’s celebrated wartime minister Stephen Johnson (1724–1784). A history of Northford’s church states that Rev. Matthew Noyes was Connecticut’s wealthiest clergyman.[2]

Matthew Noyes ordination sermon, Northford, August 18, 1790

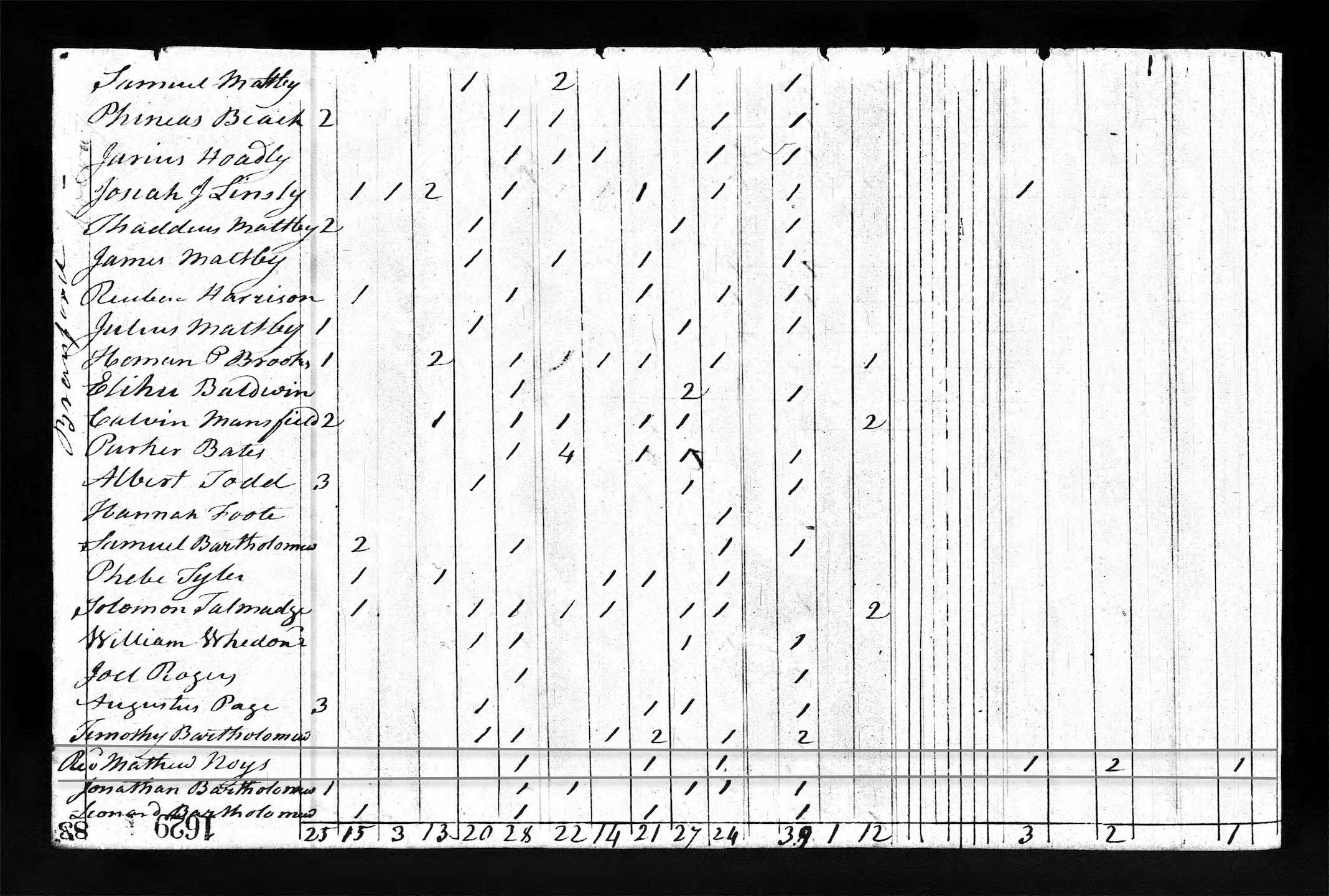

The distribution of enslaved persons within slave-holding families was common among Lyme’s prominent landowners, but such transfers were rarely documented.[3] Harry’s age when he moved to Northford is not known, but census records list one enslaved person in Matthew Noyes’s household in 1800, two free non-white persons in 1810, and four “Free Colored Persons” in 1820–a boy under 14, a young woman between ages 14 and 25, and two adult men between ages 26 and 44. One of the adult men was likely Harry, who in 1820 could well have had a wife and son.

Fourth United States Census, 1820, with Rev. Matthew Noyes household underlined

No emancipation certificate has been found for Harry Freeman, but Connecticut’s gradual emancipation law provided that any person born into slavery after March 1, 1784, would become “free” at age 25. Harry’s 25th birthday was December 3, 1815. Like his relatives in Lyme, he took, or was assigned, the surname “Freeman” to signal his changed status. Northford’s church records tell us that Rev. Matthew Noyes baptized Harry Freeman and admitted him to communion on December 1, 1816.

Harry was not the first enslaved youth that Judge William Noyes sent from Lyme to Northford. On August 21, 1795, Rev. Matthew Noyes listed the death in Northford of “Tempy, my Negro servant.”[4] No one knows at what age Temperance, Nancy’s youngest sister, left her family, but the Noyes scrapbook notes that Tempy died in Durham at age 15 while on a journey to Lyme. Presumably she planned to visit her mother Jenny, her four siblings, her nephews Jordan and Harry, and her niece Sabina, Nancy’s daughter, born in 1793.

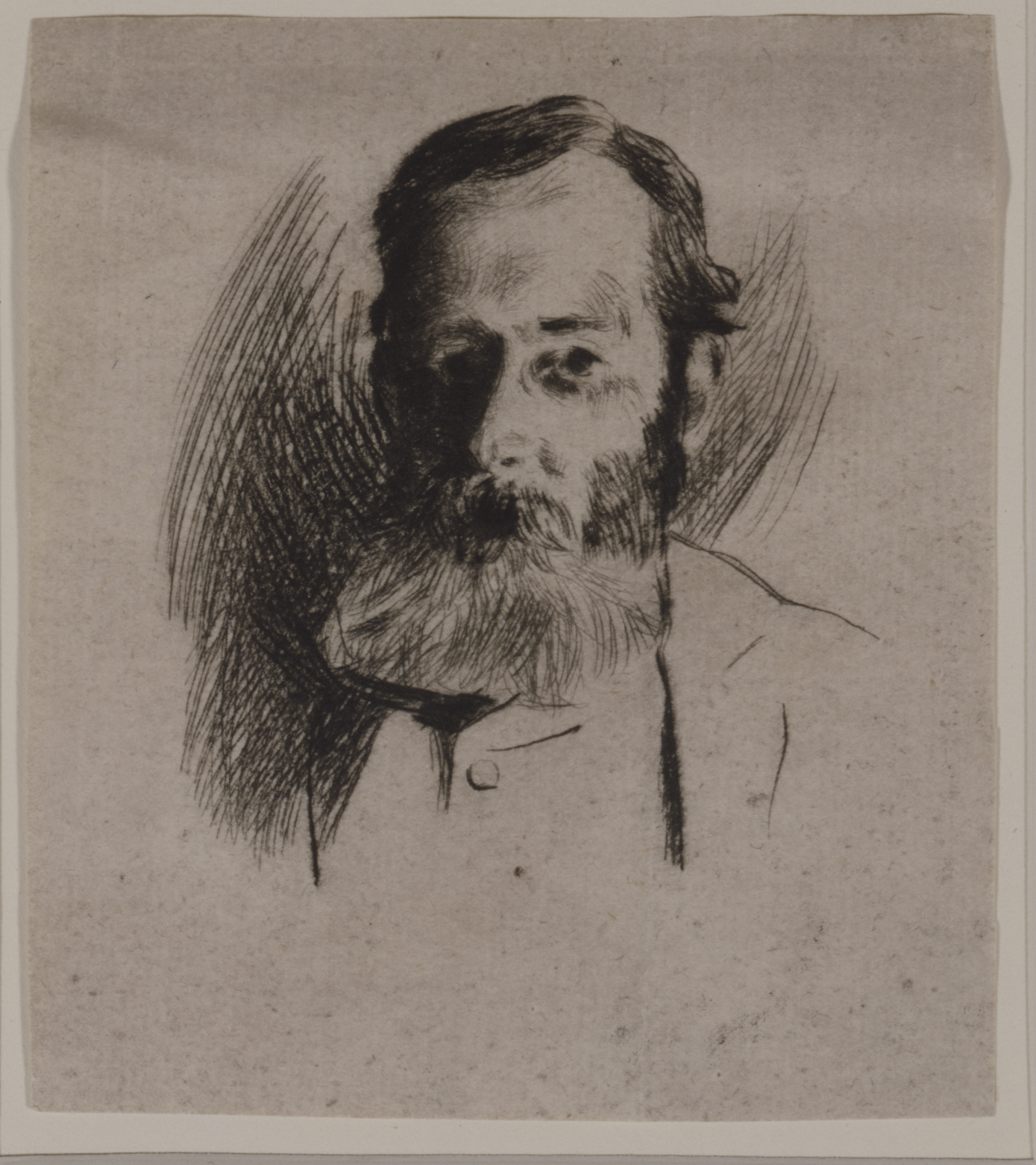

James Martin, Judge William Noyes, ca. 1798. Pastel on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, Purchase with contributions from Geoffrey Paul, David Dangremond, John & Werneth Noyes, and Gay Myers

For reasons unknown Tempy did not survive that journey. She died at the house of Col. John Noyes Wadsworth (1758–1814), Matthew Noyes’s cousin, who is listed in the 1790 census as owning two slaves. Why Tempy traveled via Durham to Lyme in the summer of 1795, whether she stopped at Col. Wadsworth’s house because she was ill, whether she journeyed on foot and alone are not known. Tempy Freeman’s name and date of death are inscribed on a gravestone in Durham’s old cemetery.[5]

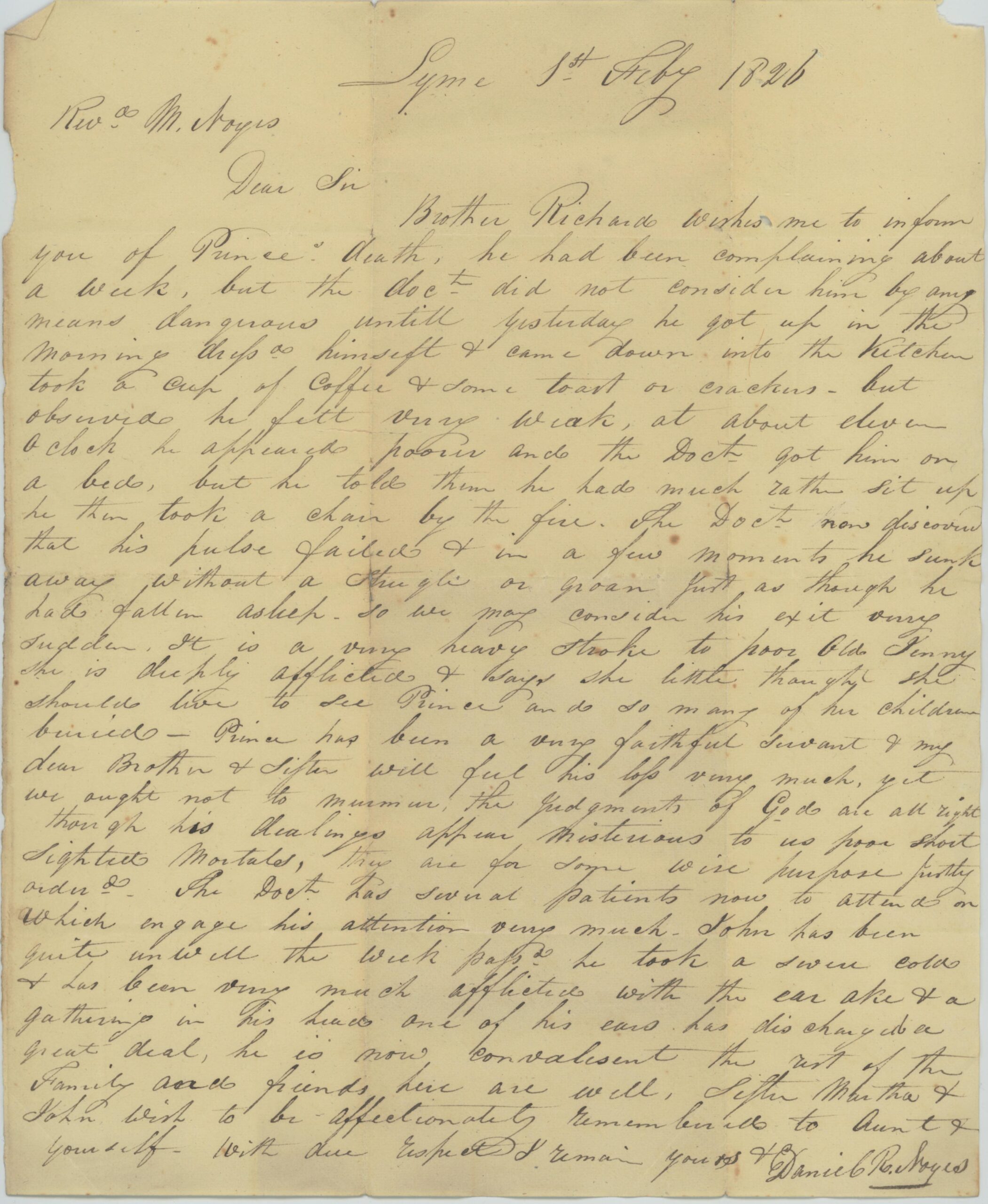

Harry Freeman was 32 when he died in Northford in 1823. Like his aunt Tempy, he was among the children whose early deaths his grandmother Jenny Freeman mourned in 1832 after her son Prince died in Lyme. “Poor Old Jenny,” Daniel Rogers Noyes (1793–1877) remarked when informing his cousin Matthew Noyes about the death of the family’s “very faithful servant.” The letter describes Jenny as “deeply afflicted” and notes that “she little thought she should live to see Prince and so many of her children buried.”

Daniel Rogers Noyes, letter to Rev. Matthew Noyes

Pompey Freeman, Prince Freeman, Jenny Freeman, Nancy Freeman grave markers, Duck River Cemetery, Old Lyme

Gravestones in Old Lyme’s Duck River Cemetery mark the passing of Jenny and her children Pompey, Prince, and Nancy. The grave marker that Matthew Noyes purchased for Harry Freeman in 1826 was placed in Northford.[6] Along with the gravestone commemorating Tempy Freeman in Durham, it documents the dispersal of children born into hereditary slavery in Lyme.

[1] Verne M. Hall & Elizabeth B. Plimpton, ed., Vital Records of Lyme, Connecticut, to the End of the Year 1850 (Heritage Books, 1990), p. 70; Noyes family scrapbook, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum.

[2] History of the Northford Congregational Church, 1750-1986, p. 5.

[3] Rev. John Ballantine of Westfield, MA, observed in 1768 that “Masters of Negroes. . .have an arbitrary power, they may correct them at pleasure, may separate them from their children, may send them out of the Country.” Cited in Joseph Carvalho III, “Black Families in Hampden County, Massachusetts, 1650-1865,” in Historical Journal of Massachusetts40 (Summer 2012), p. 64.

[4] Theodore Groom, “Remembering Gad Asher,” Totoket Historical Society (October 2013), p. 7.

[5] See Henry Greenleaf Pearson, James S. Wadsworth of Genesco (New York, 1913), p. 1. The gravestone for Temy [sic] Freeman, August 1795, is listed in the Old Durham Cemetery on Find a Grave.

[6] Charles R. Hale Record of Connecticut Headstone Inscriptions, Old Northford Cemetery, Section A #50.