Carolyn Wakeman

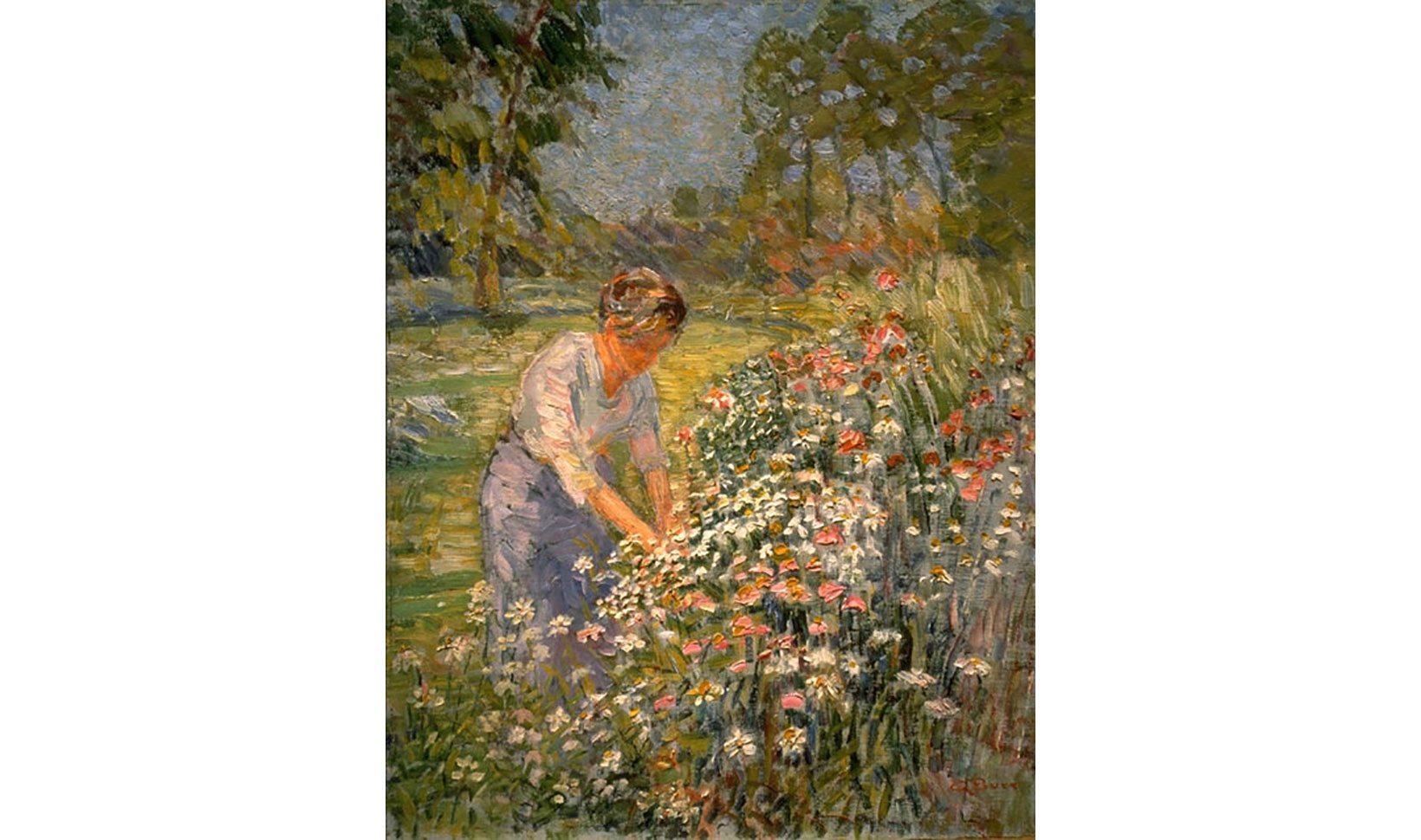

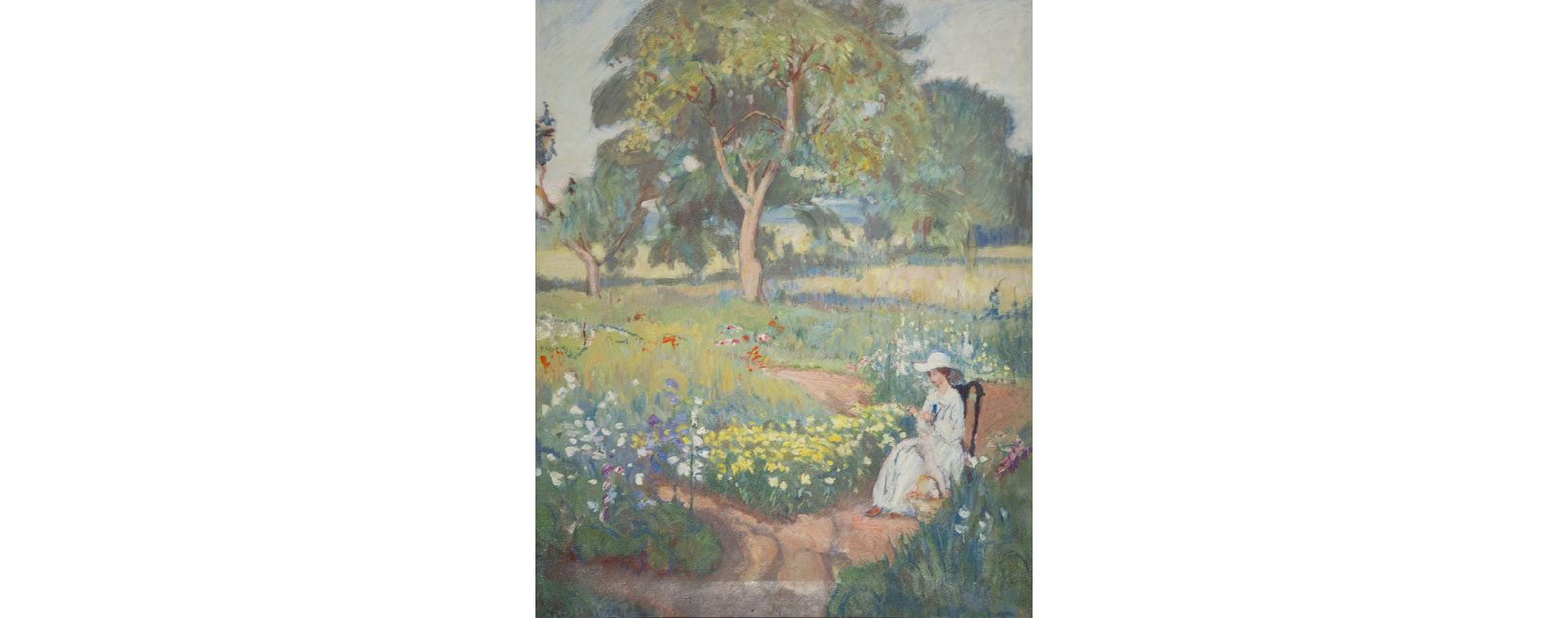

Featured Photo (above): Lucien Abrams, Garden on the Ledge, 1932. Tempera on canvas. Private collection

In the cultivated wildness of their flower gardens, local artists showcased their delight in color, pattern, and form. According to The Hartford Courant in 1931, Lucien Abrams, whose paintings are lavishly displayed in the Florence Griswold Museum’s spring exhibition Lucien Abrams: A Cosmopolitan in Connecticut, was one of several Lyme painters known as much “for their wonderful flowers and the studied care of their houses and grounds as for their pictures.” [1]

Village Gardens

The earliest ornamental gardens in Lyme appeared in village settings. Behind the late federal-style mansion of Richard Sill Griswold, Jr. (1845–1904), the Gothic cottage of John Peck Van Bergen (1821–1908), and the neo-colonial summer home of Charles H. Ludington (1825–1910), landscaped grounds before the turn of the 20th century featured manicured lawns, trimmed boxwood hedges, and geometric flowerbeds. But garden tastes had changed by the time Lucien Abrams (1870–1941) purchased property near the top of Meetinghouse Hill in 1915. Like other art colony members, he intruded dazzling summer flowers into previously undecorated terrain.

Lucien Abrams, In the Garden, 1915. Oil on canvas. Private collection

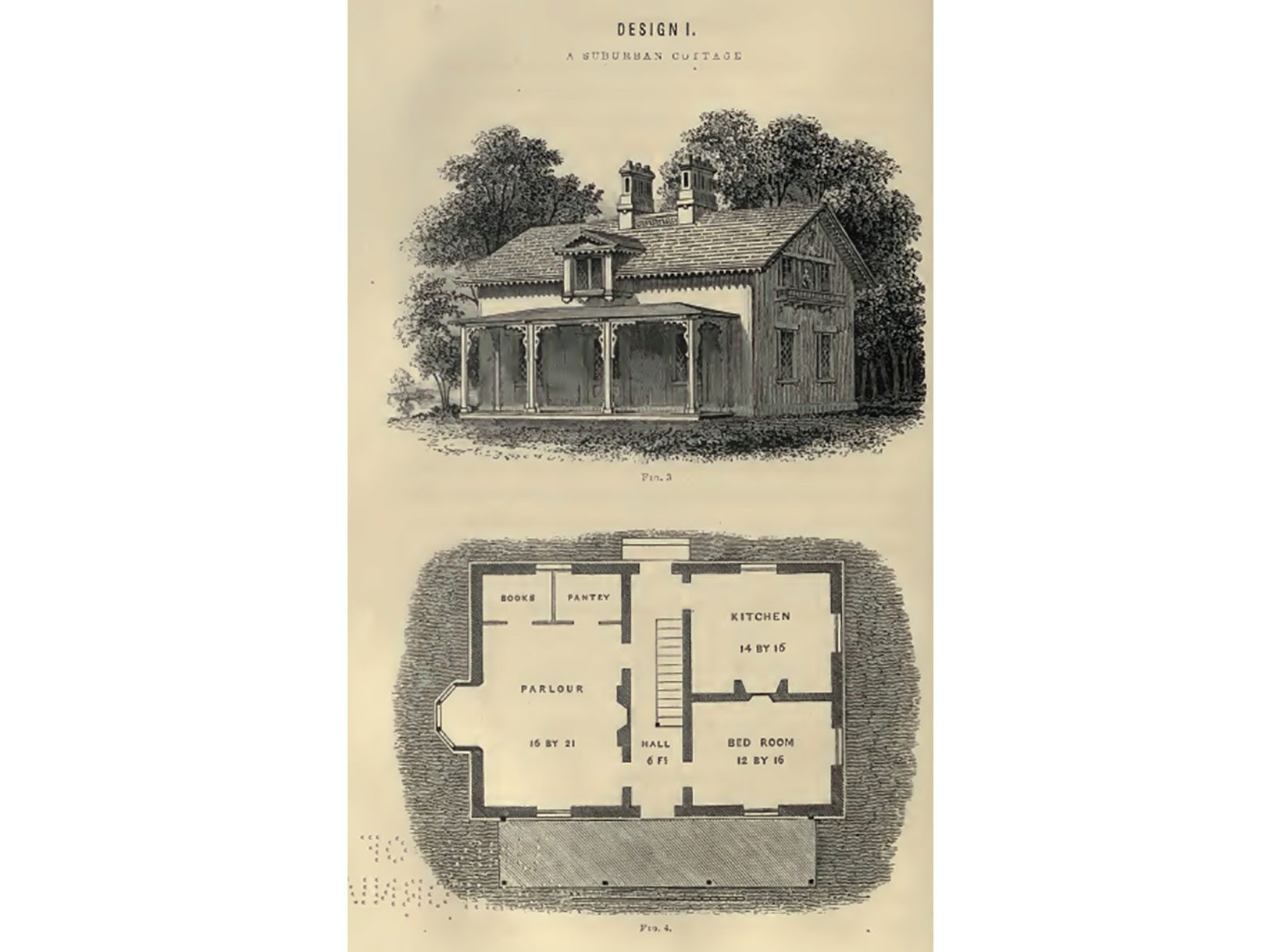

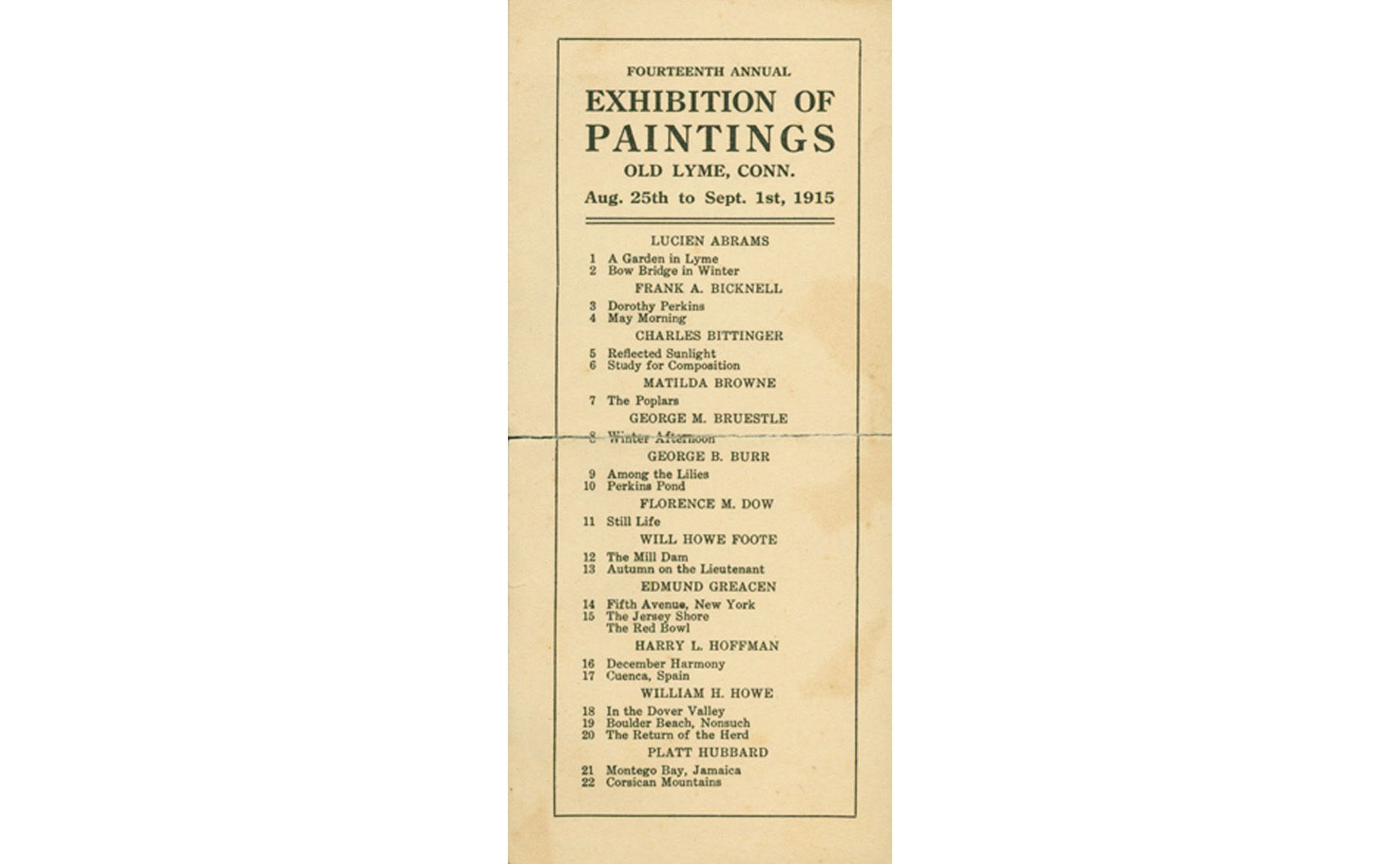

The New York Times described Abrams as a “newcomer” in 1915 when he contributed a painting of a much-admired village garden to the annual end-of-summer exhibition held in the public library.[2] Six years earlier artist George B. Burr (1876–1939) had bought the picturesque house and grounds on Lyme Street that previous owner J. P. Van Bergen named “Cricket Lawn.” Built in 1844 for local physician Dr. Shubael Bartlett (1811–1849), the house followed a design in Andrew J. Downing’s influential book of architectural plans called Cottage Residences (1842). Set back from the road with a broad veranda and south-facing upper balcony, the Bartlett residence contrasted boldly with nearby dwellings and at the time seemed startlingly modern.

Photograph from Lucien Abrams’s album showing George Burr’s house with south-facing balcony, 1924. Family of Lucien Abrams

Cottage design from Alexander J. Downing’s Cottage Residences (1842).

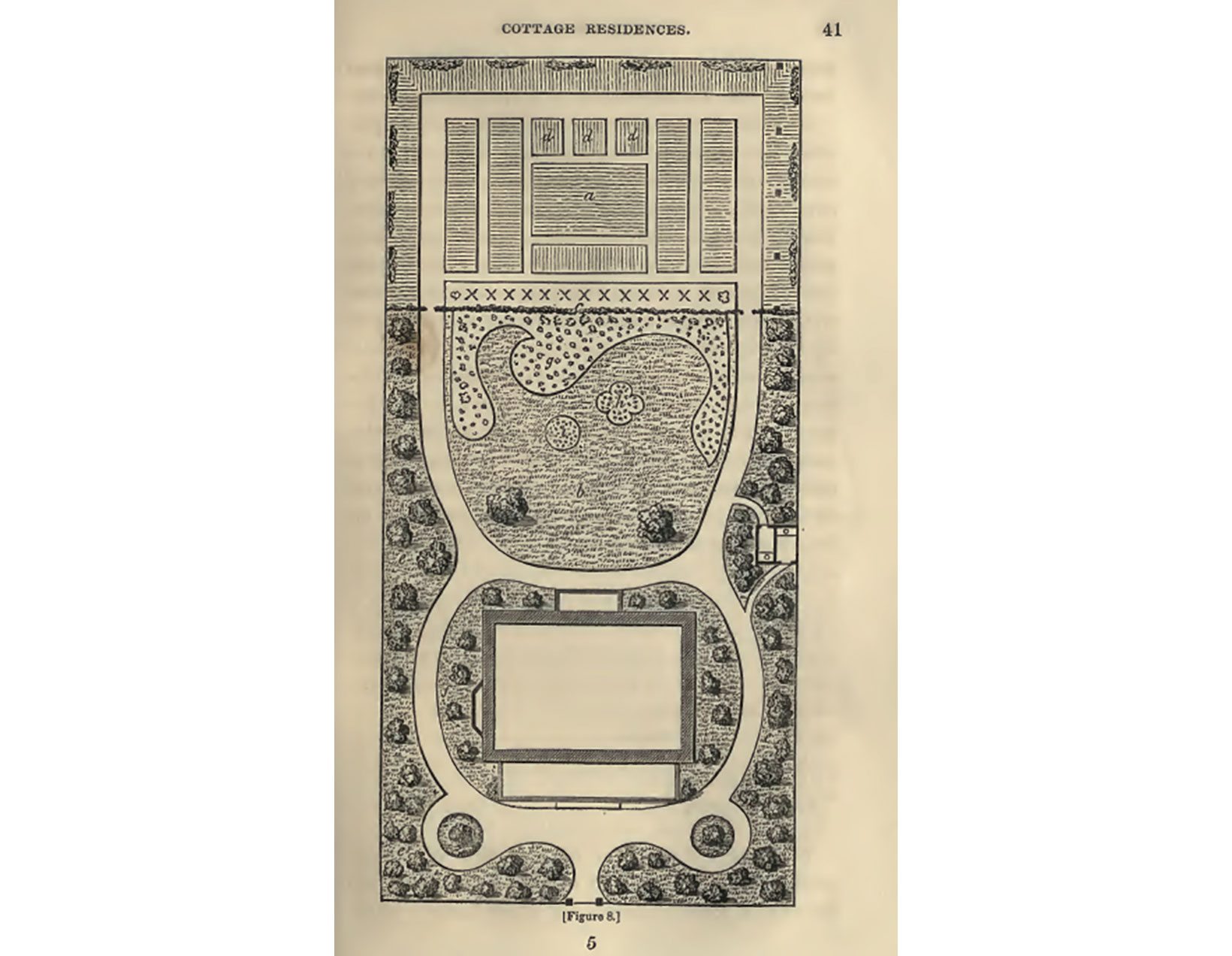

Suggested landscape layout from Alexander J. Downing’s Cottage Residences (1842)

Home of John Peck Van Bergen, called “Cricket Lawn,” ca. 1880. LHSA

When a reporter for Country Life magazine described Cricket Lawn in a feature article about Lyme artists’ residences in 1914, he remarked on its seventy-five year old boxwoods and square flowerbeds. “Roses fill the right square,” he wrote, “and the other is massed with such perennials as foxglove, peach bell, galliardia, and coreopsis, as well as some annuals.”[3] Burr had already painted his perennials in full summer bloom, and in 1915 Abrams offered a similar view of the long-established village garden.

George B. Burr, Old Lyme Garden, ca. 1913. Oil on panel. FGM, Gift of Mrs. Patricia Burr Bott, X1972.210

While obscuring the flowerbeds’ geometric shape, Abrams draws the viewer’s gaze to a garden path where a women in white sits in a decorative side chair, her knitting basket at her feet. Vivid colors and short brush strokes blend the rear meadow grasses and shade trees with the planted landscape. The New York Times’ reviewer commented that Abrams had seen an old New England garden “with the eyes of modern France” and observed how the “tangle of unconsidered yellows and reds and blues and purples in the garden bloom gains by the stylistic treatment.”[4]

George B. Burr, Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, ca. 1914. Oil on masonite. FGM, Gift of Mrs. Patricia Burr Bott, 1979.8

George Burr painting in rear garden, showing arbor with blossoming vines, ca. 1915. LHSA

Edmund Greacen, The Old Garden, ca. 1912. FGM, Gift of Mrs. Edmund Greacen, Jr., 1974.1

Over the decades Cricket Lawn invited multiple artistic treatments. When Burr painted his own flowerbeds again around 1915, he removed the delineating paths and allowed the floral display with its gently curving outer border to fill much of the canvas. His focus in Portrait of the Artist’s Wife is a woman dressed in lavender and white who seems almost to merge with the sun-drenched perennials as she works among the blossoms.

14th Annual Exhibition of Paintings, Old Lyme, 1915. Courtesy Carolyn Wakeman

Mahonri Young, The George Burr House in Winter, 1942. FGM, Gift of Daniel J. and Gertrude W. Tucker, 1984.24

But Edmund Greacen (1877–1949) eliminated both paths and human figures from his impression of the same landscape. A blurred expanse flowers, shrubs, shade trees, and meadow immerses the viewer directly in the garden setting.

It was not summer flowers but a pallid winter landscape that Mahonri Young (1857-1957) portrayed while visiting his sister-in-law next door in February 1942. The George Burr House in Winter shows the north side of the neighboring cottage from artist Caro Weir Ely’s (1884–1974) side porch. A tangle of bare branches and an expanse of snow-covered lawns and shrubs surround Cricket Lawn at a moment of wintry solitude.

Flowering Riverbank

By 1914 at least fourteen artists had purchased homes in Lyme, drawn by the varied beauty of the landscape and the companionship of other painters gathered at Florence Griswold’s boarding house. Old-fashioned flowerbeds behind her barn offered inspiration for their own gardens, and Miss Florence provided both seeds and advice to encourage their landscaping efforts. One of the first art colony members to purchase property away from the village was Clark Voorhees, whose gardening transformed a riverbank.

Clark Voorhees’s house before garden installation, 1907. LHSA

Clark Voorhees’s house showing Calves Island Sound, 1907. LHSA

For almost two centuries his gambrel-roofed colonial house squeezed between the Neck Road and the Connecticut River had overlooked a working waterfront. Capt. Joseph Higgins (1690–1783), who acquired the house from Richard Mather in 1740, built a wharf and warehouse to support his activities in the West Indies trade. But even from the time of the early settlement, farmers had landed barges of salt hay and fishermen had barreled shad along that protected shoreline. Clark Voorhees was the first to envision the riverbank across from Calves Island as an ornamental setting.

In 1914 the wharf still served as a coal dock when Voorhees and fellow artist Matilda Browne both painted the swath of perennials blossoming on the terraced bank and the stone steps leading to an upper lawn. Each composition includes a child in white who visually connects the lower gardens with the white house sheltered by shrubs, vines, and overhanging branches. The Country Life writer who visited the gardens that year noted the “artemesias on each side of the door and also some hardy primulas that Mrs. Voorhees dug up in Italy and brought to Lyme.”

Matilda Browne, In Voorhees’s Garden, 1914. FGM, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company

Clark Voorhees, My Garden, 1914. Private Collection

Matilda Browne, Clark Voorhees’s House, ca. 1914. FGM, X1972.219

Matilda Browne captured both the intimacy of the dooryard and the expansive view across the salt meadows to the Essex shoreline when she painted the Voorhees house again, perhaps in the same year. A green chair and a hanging birdcage along with potted peonies, climbing vines, and a boxwood topiary decorate the side porch and convey a feeling of welcome, comfort, and domesticity.

Landscaped Ledge

In generations past Lucien Abrams’ property on Meetinghouse Hill would also have been considered an inhospitable spot for ornamental gardening. Lyme’s early residents had gathered across the road at three successive meetinghouses to attend town meetings and Sabbath sermons, and sheep had long grazed amid the granite outcroppings. But by 1929 Abrams had installed perennial beds, roses, pergolas, grape arbors, and a rock-rimmed goldfish pool on his scenic grounds.

Lucien Abrams’s garden, with stone terracing and goldfish pond, 1929. Family of Lucien Abrams

Lucien Abrams’s garden, 1929. Family of Lucien Abrams.

Lucien Abrams’s house, with rose garden, 1929. Family of Lucien Abrams

He had also transformed the gambrel-roofed dwelling once owned by Thaddeus P. Fanning (1815–1863), who operated a blacksmith shop on the premises.[5] Abrams’ photograph albums document both the creation of the gardens and the multiple additions that expanded a modest colonial home. An undated engraving by Bertha H. Dougherty (1883–1969), used later by Gina Abrams as a Christmas card, shows the gracious south-facing front entryway and the artist’s studio.

Abrams’ Garden on the Ledge, exhibited at the Lyme Art Association in 1932 and priced at $1,200, offers a vividly colored impression of his Meetinghouse Hill setting. In this sweeping view of the grounds in full summer bloom, creamy white yucca blossoms with spiky green leaves lead to a line of boulders sketched in orange, yellow, and green and dotted with poppies and irises. A solitary red cedar draws attention to a distant lighthouse.

Lucien Abrams’s hillside, with granite ledge and yucca plants, 1929. Family of Lucien Abrams

Bertha H. Dougherty, Lucien Abrams’s Studio, n.d. Private collection

Abrams seems to have taken liberties when depicting his landscape. Even without the tree cover now concealing the Connecticut River, it is difficult to discover a vantage point from which he could see simultaneously the line of flowering ledge, a wing of the house, and a glimpse of Saybrook Point. His painting likely offers a composite vision. Just as he augmented the shapes and colors of boulders, flowers, and trees, so he may also have adjusted the perspective to draw together the scenic features of his grounds. He had already remarked the previous year that the intention of his landscapes was not to copy nature but to interpret it.[6]

Today changing tastes and lifestyles have diminished the gardens that Abrams and other Lyme art colony members created a century ago in sometimes unexpected settings. Without their paintings and photographs the spectacular flowering landscapes that they designed, planted, and maintained would have disappeared from view.

[1] Special thanks to Amy Kurtz Lansing and David Dangremond for generous assistance. See The Hartford Courant (August 30, 1931).

[2] The New York Times (August 29, 1915).

[3] H. S. Adams, “Lyme—A Country Life Community,” Country Life in America (April 1914), Vol. 3, p. 94.

[4] The New York Times (August 29, 1915).

[5] Old Lyme Land Records, 1:318.

[6] Artists’ files, Florence Griswold Museum.