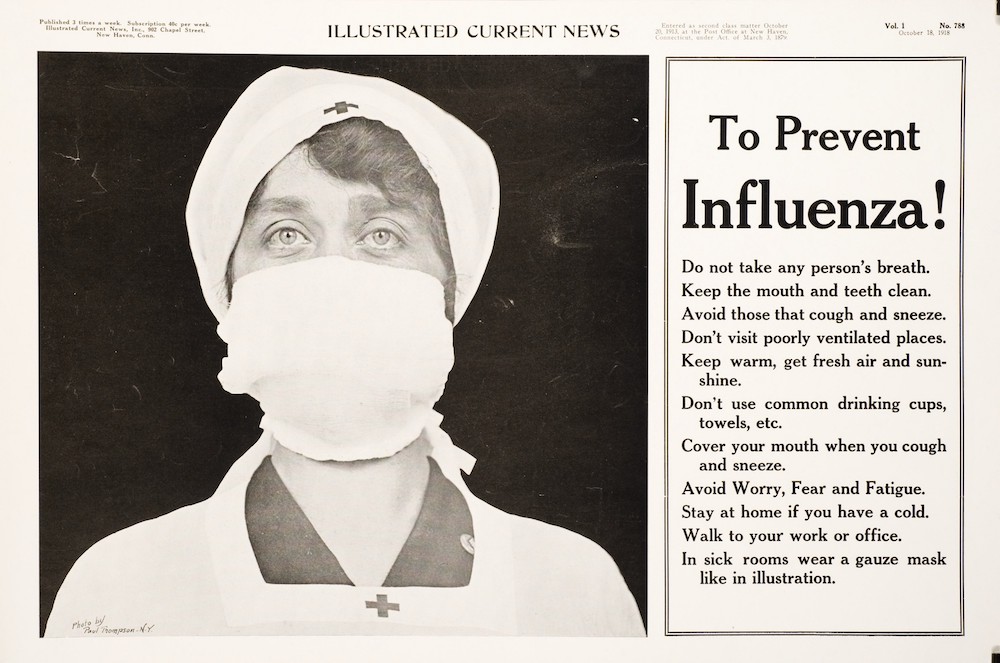

As Connecticut battles a deadly pandemic in 2020, with 36,703 cases and 3,339 deaths reported as of May 16, we remember that communities like Old Lyme faced an even graver threat from influenza a century ago, when illness struck during the First World War.

By Carolyn Wakeman

Featured Image: Paul Thompson (photographer), “To Prevent Influenza!” Illustrated Daily News, New Haven (October 1918)

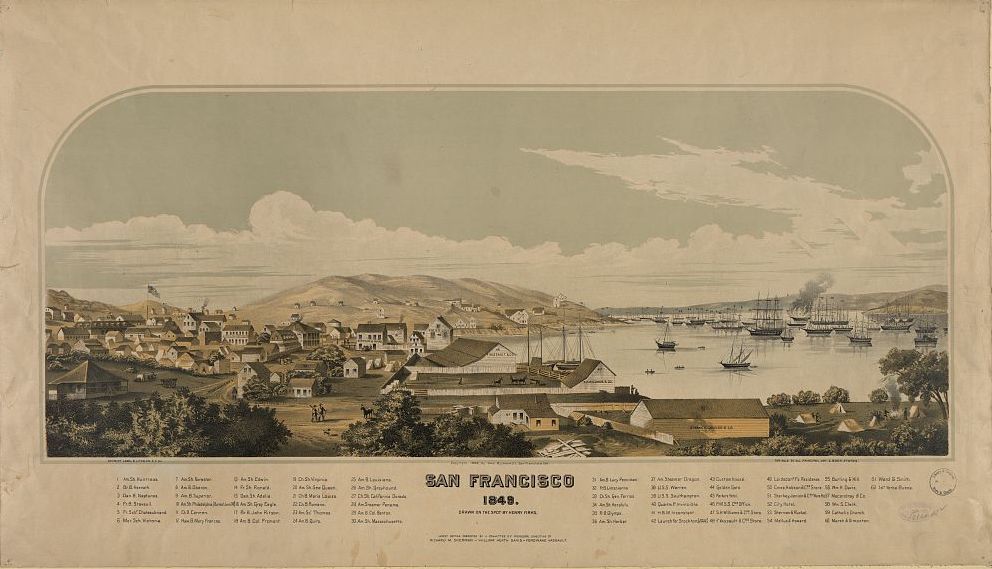

An estimated 675,000 people died in the United States when a raging viral illness swept through the country during World War I, spiking again in early 1919 after fighting had ended. In Connecticut, where 8,500 people died, “the epidemic of influenza was a blasting thing, many times more devastating than the war,” the Connecticut Health Bulletin reported. Military bases, crowded with recruits preparing for deployment in Europe, became early breeding grounds for influenza. The first cases in Connecticut appeared at the Naval Hospital in New London in early September 1918, and infection spread rapidly among the civilian population. When the epidemic “overran the State” in October, Connecticut’s State Council of Defense issued thirty thousand posters giving “rules for avoiding influenza.”[1]

Town of Old Lyme, Financial Report, 1919, Old Lyme Town Reports, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum.

“So serious was the epidemic,” Old Lyme’s health officer noted in the town’s Financial Report, “that the Federal Government took control of New London County, and all Health officers were placed under Federal Health supervision and detailed reports of each case, its location, sanitary conditions and other important data was reported to the Federal Health Board every twenty-four hours.” The severity of the health threat in New London had not at first been recognized, and the Norwich Bulletin, reporting on the outbreak nearby, used a familiar term for a common illness, stating on September 14 that an “Epidemic of Grip Strikes the City.” Two weeks later more than 600 cases of influenza had been reported in New London, and sixteen servicemen along with eight civilians had died. On September 27 the city’s board of health ordered the closing of theaters, churches, schools, dance halls, and “meeting places of all kinds except saloons.”[2]

“For Grip and colds that develop into Pneumonia,” advertisement, Norwich Bulletin (October 3, 1918)

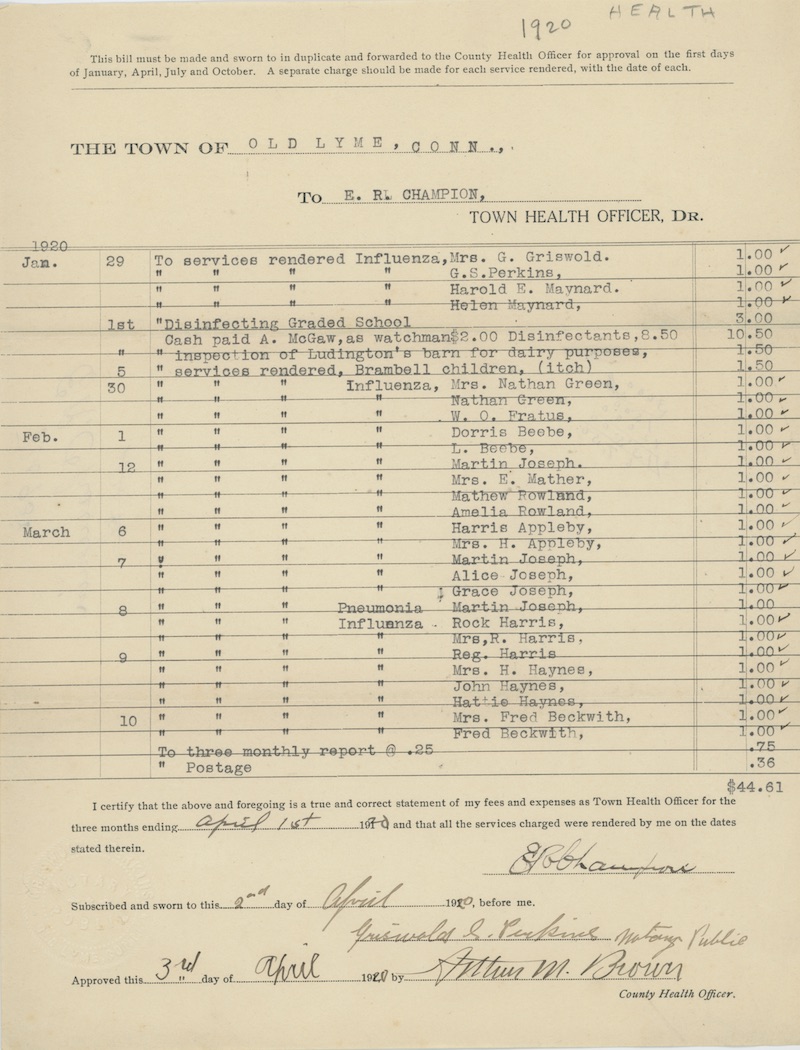

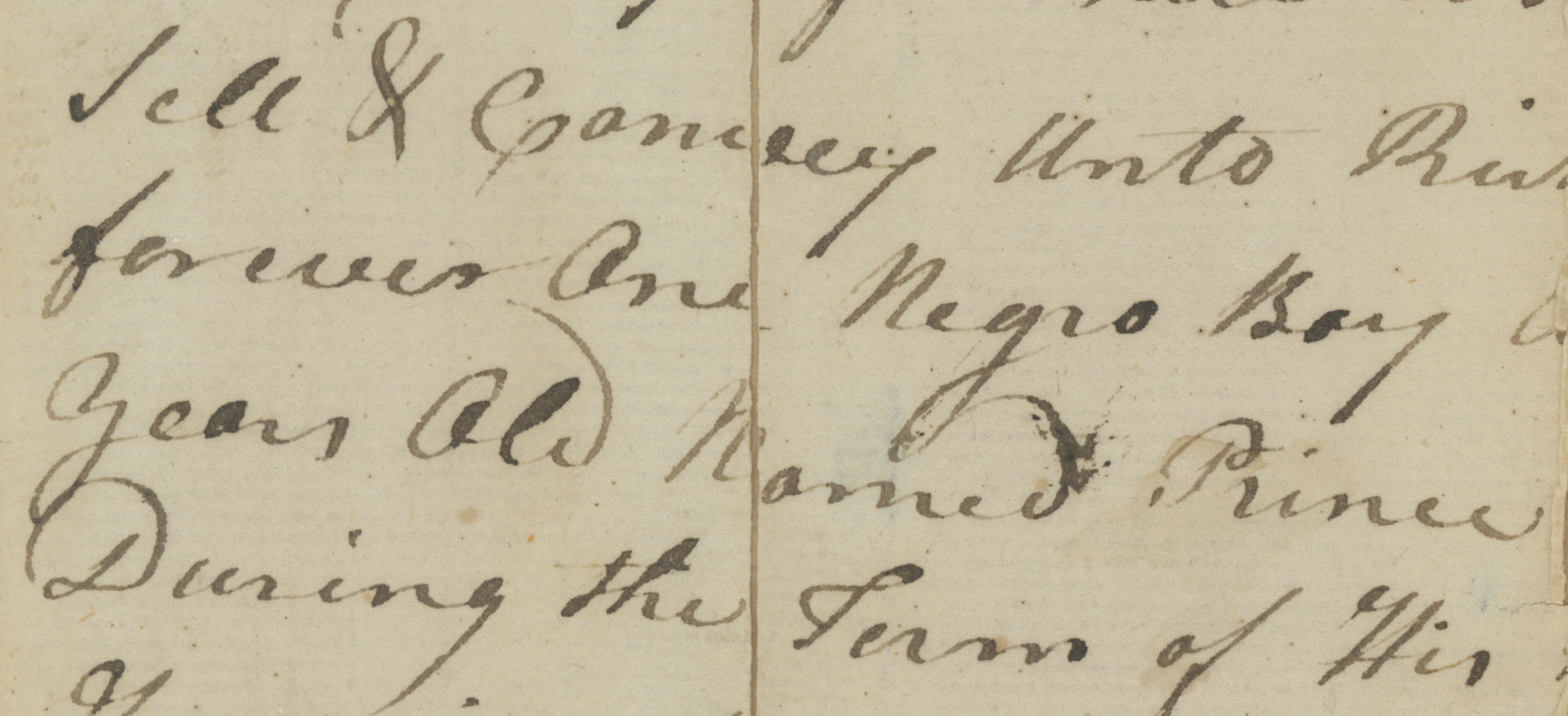

In a report to Old Lyme’s Board of Selectmen for the year ending August 1919, Edgar R. Champion (1872–1930), the town’s pharmacist and its health officer, outlined the scope of the local epidemic. “In the early part of September, this town passed through one of the most serious times in its existence health-wise,” he stated. “An epidemic of influenza result[ed] in one hundred and forty-eight reported cases, in which five deaths occurred either from this epidemic or the resulting pneumonia.” The town’s Board of Health stated an even higher number, reporting 174 influenza cases during that twelve-month period. In the 1920 federal census, Old Lyme’s population would be listed as 946.[3]

E. R. Champion, Charges for Influenza Services, January-March, 1919, Old Lyme Town Papers, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

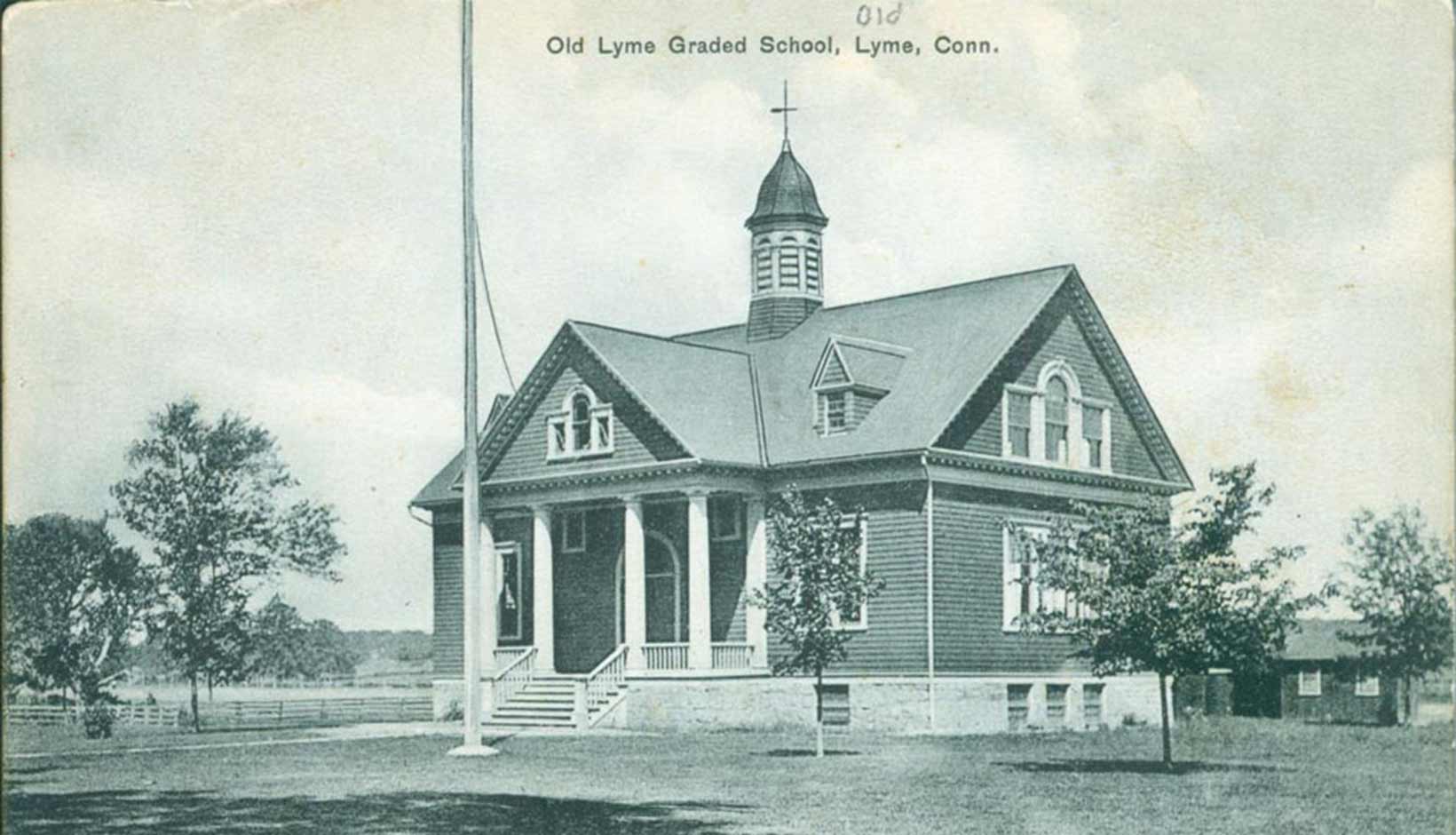

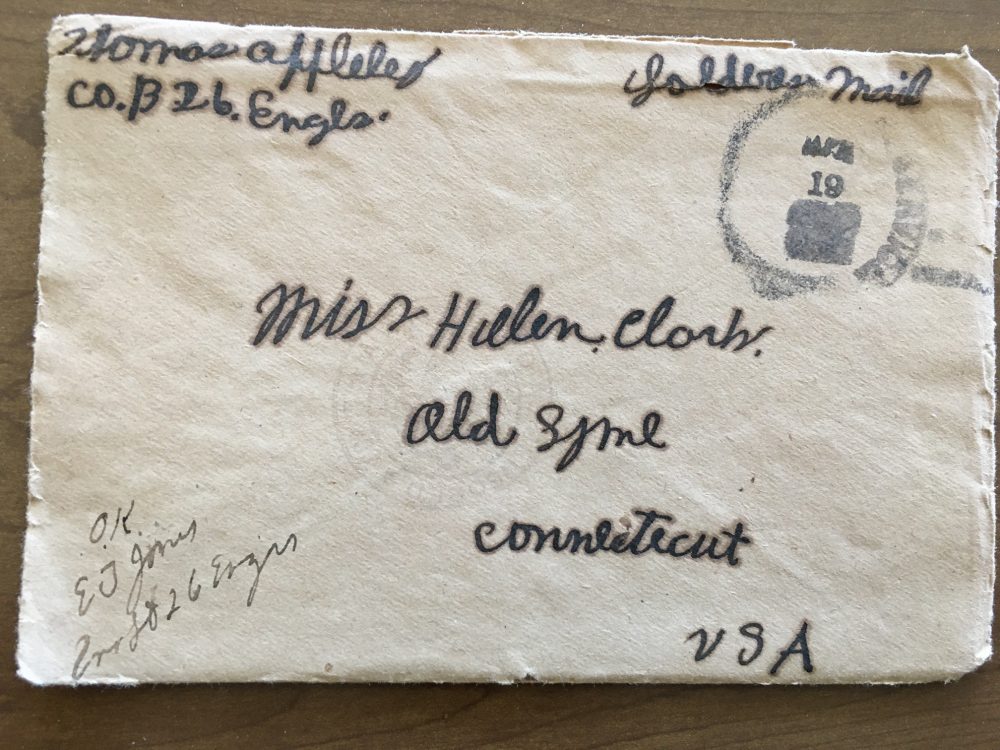

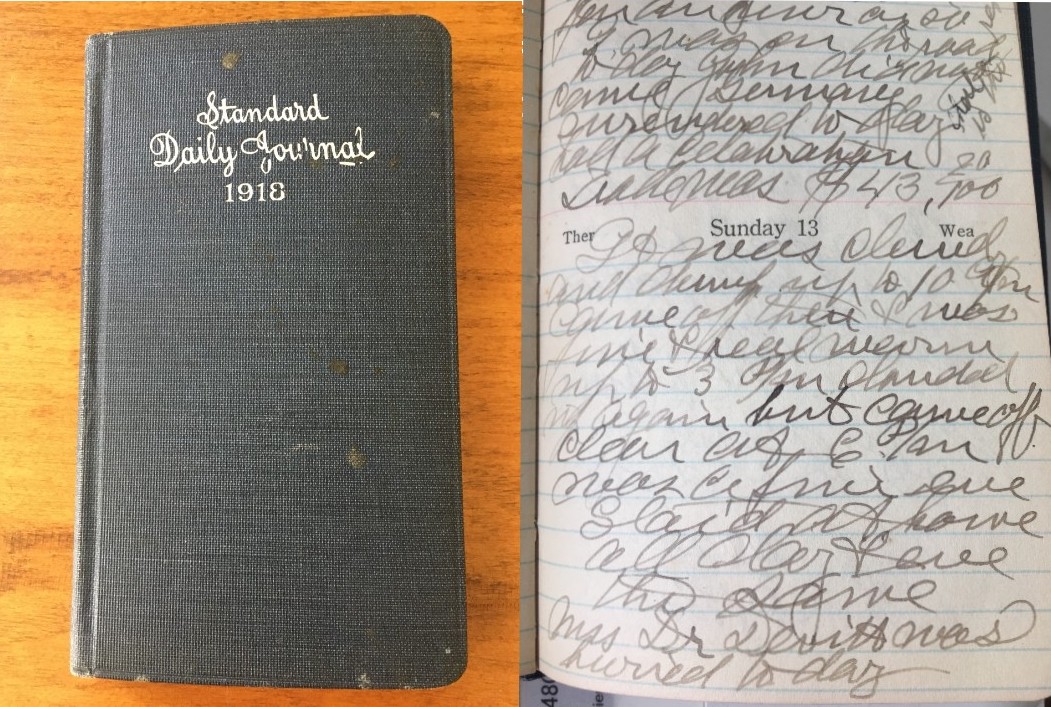

Family letters, a diary, a notebook, and a local newspaper offer glimpses of the epidemic’s impact in Old Lyme. Postmaster W. F. Clark (1850–1927) noted in his daily journal on September 28, 1918: “Everything shut up on account of the grip.” A month later the Deep River New Era reported: “Health Officer Champion lifted the quarantine in Old Lyme Tuesday morning.” At a November meeting the local Red Cross chapter expressed thanks to the school board for keeping the building heated when the school was “closed by the influenza,” allowing the women’s sewing work for war relief to continue. When the epidemic surged again in the spring, Mr. Clark named in his diary five people who died over four days in a single week in mid-April. “So many deaths just now,” he noted.[4]

Old Lyme Graded School, Lyme, Connecticut. Postcard. Collection of Carolyn Wakeman

W. F. Clark, ca. 1910. Courtesy Carolyn Wakeman

His daughter Helen Clark (1892–1988) worried not only about those stricken with influenza at home but also about those serving with the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe during what was a global pandemic that killed over 50 million people worldwide. While waiting anxiously for her future husband Jack Speirs (1890–1984) to return from France, she learned of the death in January of their friend Tom Appleby (1890–1919) at a military hospital near Bordeaux. After the armistice in November had ended fighting in Europe, the two soldiers from Old Lyme, who served together in an engineering battalion, had been assigned to a crowded debarkation camp to await passage home.

Tom Appleby to Helen Clark, Carte Postale with embroidered handkerchief, mailed from France (April 15, 1918). Janet Speirs York collection

“I am wondering if you got to the hospital to see Tom,” Helen asked in a letter to Jack in early February. “I suppose, like all the recent pneumonia cases, his illness was short.” Her reference to recent cases recalled the sudden death from influenza a month earlier in New Haven of Jack’s younger sister Janet Speirs Walker (1892–1918), who was 26 and pregnant with twins. “It is dreadful to be held, waiting for transport so long,” Helen added. “I wouldn’t mind waiting as much, if I only knew you were keeping well. But now-a-days sickness and death come so quickly!”[5]

Thomas Appleby, 1918. Connecticut WWI Military Questionnaires, 1919–1920. Connecticut State Library, Hartford, Connecticut, accessed via Ancestry.com

Thomas Appleby, 1918. Connecticut WWI Military Questionnaires, 1919–1920. Connecticut State Library, Hartford, Connecticut, accessed via Ancestry.com

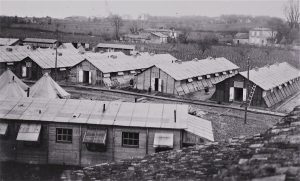

Camp hospital 2, Bordeaux, 1919

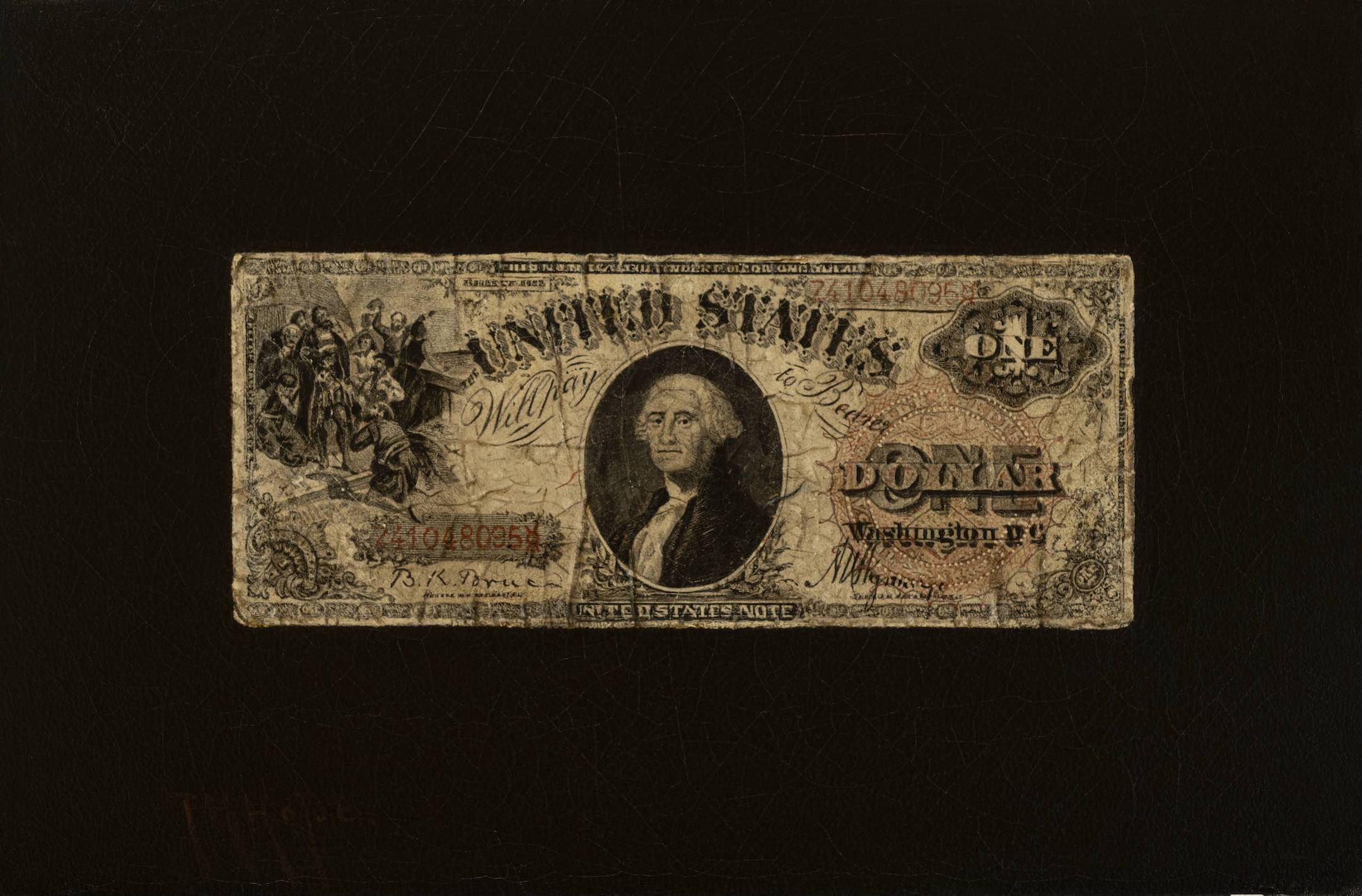

War and illness entwined in the lives of Old Lyme’s residents. During the early months of 1919 when Pharmacist Champion provided influenza services for those stricken in town, his son also waited in a debarkation camp to return from France. Edgar W. Champion (1894–1979) sailed from Brest to Boston on a troop transport on March 31. His father, who opened a pharmacy in his family’s “Corner Store” after graduating from the Columbia College of Pharmacy in New York, had assumed the role of public health officer when the town’s doctor Ellis K. Devitt (1880–1958) enlisted in the Medical Reserve Corp. A week after Dr. Devitt reported to a hastily built tank training school at Camp Polk in Raleigh, N.C, on October 3, 1918, his wife Carman Davis Devitt (1892–1918), age 26 and a former telephone operator, died of influenza at her parents’ home in New London. “Mrs. Dr. Devitt was buried today,” W. F. Clark noted in his diary on October 13.[6] The New Era reported that her sudden death “was a severe shock to her many friends and to all in the company who knew her.”[7]

Diary entry, W. F. Clark, Standard Daily Journal (October 13, 1918), courtesy Carolyn Wakeman

The influenza epidemic also affected Old Lyme’s artists, who had viewed the town as a scenic refuge from the social ills of crowded and industrializing cities. One of the earliest impressionist painters to gather at Florence Griswold’s boarding house, Clark Voorhees (1871–1933), purchased a home on Neck Road in 1903 but left town with his family after the influenza outbreak in the autumn of 1918. The decision to spend the winter months in Bermuda, he said, was made partly so he could paint and partly to escape the flu epidemic.[8]

Clark G. Voorhees, Landscape by Moonlight, Bermuda, ca. 1919. Oil on canvas, 28 x 36 in. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. James B. Murphy II, 1988.9

William Henry Howe (1846–1929) had summered in Old Lyme since 1900 and often stayed with his wife Julia Clark Howe (d. 1937) at Miss Florence’s boarding house. After returning to his home in Bronxville, New York, in October 1918, he wrote to let her know that they had “reached home all OK,” but that the epidemic there was “fearful.” The hospital was full, he noted, and the “Episcopal Parish house [had] turned into a Hospital—40 beds and all full.” A friend’s son-in-law “was taken and dead within a week leaving two little children,” and “many deaths have been here especially among the servants.” Howe mentioned that “two sisters that were with one of our friends for years dies [sic] within two days of each other,” and that he was trying to rent their house for a year so they could “get out—god knows where.” He closed his letter to Miss Florence with concern for her health: “Hope you will keep from it.”

William Henry Howe, Pasture, 1904. Oil on panel, 11 7/8 x 16 in. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Ethelinda Griswold Rice Free, 1985.31.2

[1] Special thanks to Amy Kurtz Lansing and Mell Scalzi for research assistance. John T. Black, “The Epidemic of Influenza in Connecticut,” Connecticut Health Bulletin (April 1919), p. 10; Report of the Connecticut State Council of Defense (December 1918), pp. 46, 86; John Ruddy, “Life and death in the great 1918 influenza pandemic,” New London Day (March 15, 2020); Carol R. Byerly, “The U.S. Military and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919,” Public Health Reports (2010), pp. 82-91.

[2] Norwich Bulletin (September 14, 1918; September 27, 1918).

[3] Financial Report, Town of Old Lyme, year ending August 31, 1919, p. 34, LHSA. The Public Documents of the State of Connecticut (Hartford, 1921), pp. 48, 54, record 105,056 cases of influenza in New London County in 1918, with 1,777 cases and 212 deaths in New London, 715 cases and 209 deaths in Norwich, 204 cases and 8 deaths in East Lyme. Salem and Lyme each had 10 cases of influenza in 1918 and no deaths.

[4] W. F. Clark, Standard Daily Journal (September 28, 1918, April 24, 1919), Janet Speirs York collection; Deep River New Era (October 25, 1918); Old Lyme Red Cross notebook, 1918-1919 (November 30, 1918), LHSA.

[5] Helen Clark to John J. Speirs (February 8, 1919, February 18, 1919), Janet Speirs York collection.

[6] U. S., Army Transport Services, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939; Carolyn Wakeman, The Charm of the Place: Old Lyme in the 1920s (Old Lyme, 2011), p. 54; Norwich Bulletin (October 14, 1918); Clark, Journal (October 13, 1918).

[7]“Tribute to Mrs. Devitt,” New Era (Deep River, CT), December 13, 1918.

[8] Barbara J. MacAdam, “Clark G. Voorhees, 1871–1933,” in Clark G. Voorhees, 1871 – 1933 (Old Lyme, Conn.: Florence Griswold Museum, 1981).