By Patty Devoe

Featured Image: Lieutenant William Platt Hubbard, American Red Cross, Paris, November 18, 1918. Platt Hubbard Papers, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

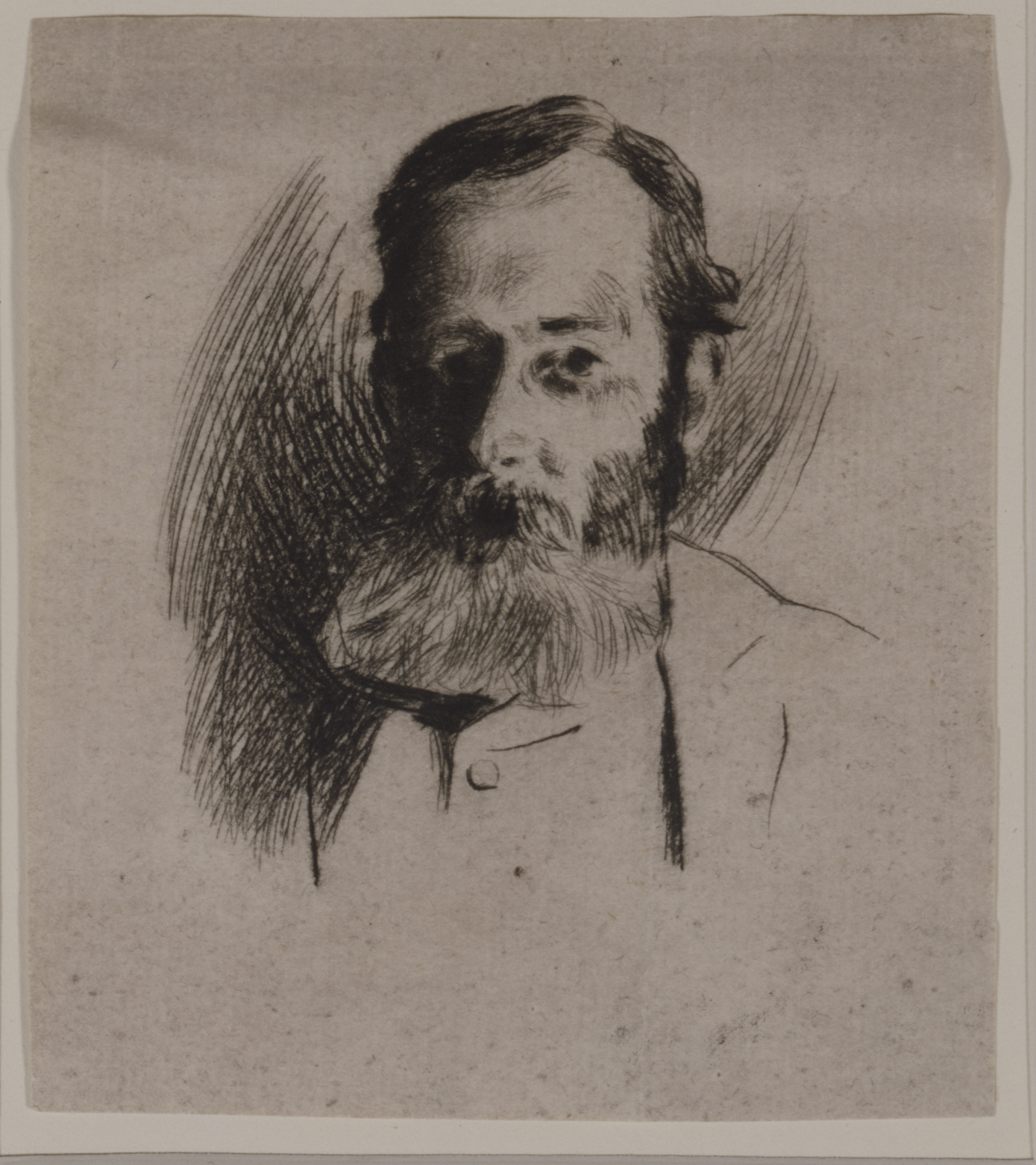

In 1914 Robert Elmer Booraem (1858-1918) wrote from his home in New York to (William) Platt Hubbard (1889-1946) at his Paris apartment. Booraem was a descendent of original 17th century Dutch settlers and amassed a fortune in mining. Platt Hubbard, a painter and etcher and member of the Lyme Art Colony, maintained a studio apartment in the vibrantly creative Latin Quarter of Paris for 20 years (1911-1932). The letter, a pleasant and seemingly solicitous one, included a photo of a nude male as well as Booraem’s personal “Cable Code.”

Robert E. Booraem, Union Club, New York. Cable Code, 1911. Platt Hubbard Papers, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

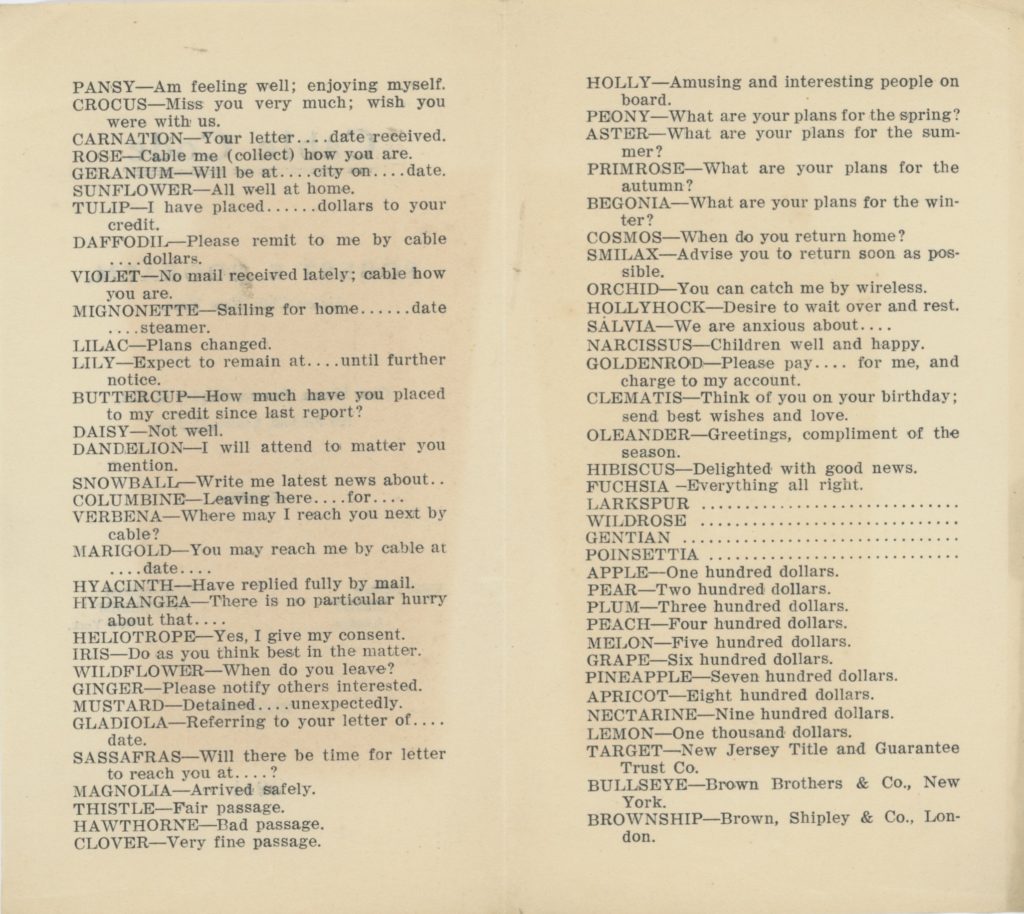

Cable codes were published directories of words that would be used in cables or telegrams and understood by the reader to represent something more than what was literally written. How else could one send private and discreet telegraph messages to one another, messages that would be read by operators on both the sending and receiving ends without using some sort of obfuscation. For example, a telegram using Booraem’s cable code might read: “MUSTARD GERANIUM PARIS RITZ SIXTEENTH,” which meant “Detained unexpectedly. Plans changed. Will be at Paris Ritz on the 16.”

Robert E. Booraem, Union Club, New York. Cable Code, 1911. Platt Hubbard Papers, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

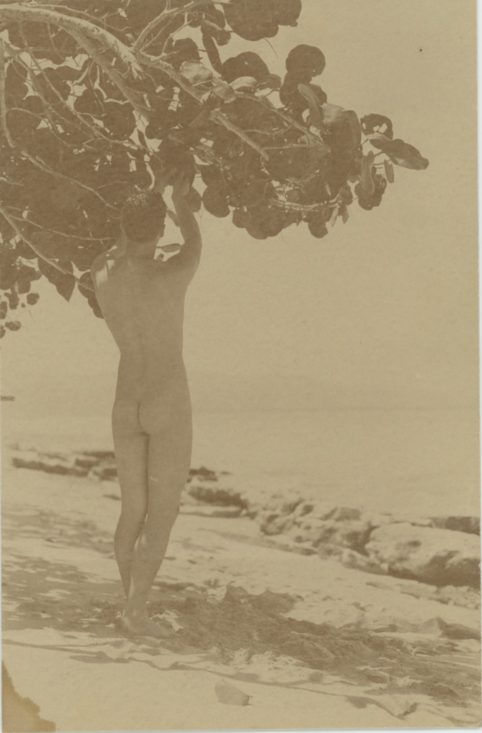

The cable code enclosure Platt Hubbard received would seem to invite him to be in touch in a most secure and private manner, and the accompanying letter described, in a flirtatious way, a trip Booraem had taken with a young Chicagoan. Booraem wrote, “He has many accomplishments in way of personal beauty, a figure art would do well to perpetuate: maybe he’ll pose for you one of these days.” The letter continued, “Your own nature surpasses his in some important ways and you can easily hold your own. I wish I were with you to illustrate what I mean.”

Photograph of unidentified nude male figure sent to Platt Hubbard by Robert Booraem, ca. 1914. Platt Hubbard Papers, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

Booraem chose the wording of his letter carefully, reflecting the caution required in 1914 by a man sending another man a nude photo and suggestive commentary by post. While homosexuality was not illegal in Paris, where Platt received his mail, under New York law such conduct was a felony, even if private and consensual.[1] The Comstock Act of 1873 also outlawed the dissemination through the mail of material deemed obscene or immoral. Booraem’s understated language and sharing of the cable codes were precautions for both men, since the meaning of any further communications would not be apparent to those without the key. The floral words that make up Booraem’s cable code also offer a twist on the sentimental “language of flowers,” in which blossoms were associated with feelings as a way of expressing love and romance throughout the nineteenth century.

In addition to personal cable codes, commercial code books, such as the Acme Commodity and Phrase Code (1923), were published as early as the 1870’s and as late as the 1950’s. Presumably the telegraph operators were not privy to these publications. Privacy was an important benefit of cable codes, but they were also used as a cost saving measure. As one cable code word represented an entire phrase, use of cable codes, commercial or private, shortened the length of a message, which would be priced according to the number of words it contained. The personal cable code that Robert Booraem sent to Platt Hubbard reflects the prominent New Yorker’s importance in business and social circles but also gave cover to pursuits in his personal life.

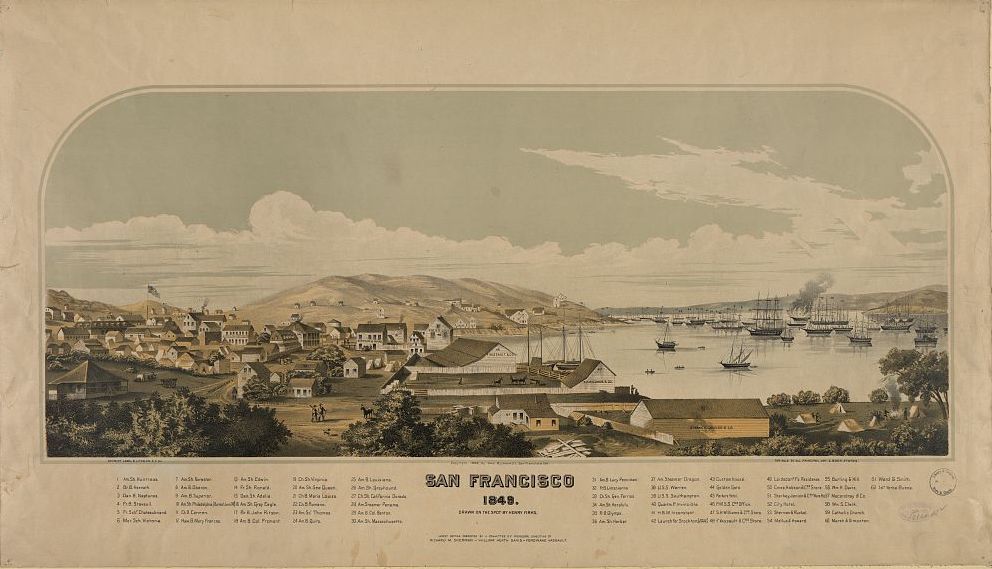

Booraem’s friendship with Hubbard would continue at least for the next several years. The Museum’s archive of Hubbard’s correspondence includes both communication with and mentions of Booraem. Booraem telegraphed Hubbard in San Francisco in 1916 with an invitation to join him at Ocean Park, in Santa Monica. The artist’s mother, Susan Platt Hubbard, offers a portrait of Booraem in a letter she wrote to her son’s partner Walter Magee in 1917, while mother and son were at a hotel in New York City:

Soon after you left the telephone rang and it was Booream and he came up & was so nice. I felt a piece of Fifth Avenue had walked into the room as he had the silk hat and all. He was chatty & amusing & helped.

Booraem passed away in Bronxville, New York, in September 1918, following a long illness. His obituary mentioned that he never married.[2]

Special thanks to Roberta Muñoz, Librarian at the Union Club of the City of New York, for her generous research support.

See Robert E. Booraem to William Platt Hubbard (July 27,1914). Platt Hubbard Collection, File Number 150-130; Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum.

For more information about Robert Elmer Booraem, see The Anaconda Standard (October 20, 1918), p, 3; Prominent Families of New York (New York, 1898), pp. 71-72.

For more information on cable codes, see https://jmcvey.net/cable/intro.htm; Steven M. Bellovin, “Compression, Correction, Confidentiality and Comprehension: A Look at Telegraph Codes” (Columbia University, July 27, 2011 (https://www.cs.columbia.edu/~smb/papers/codebooks.pdf).

[1] Act of Mar. 3, 1886, ch. 31, sec. 6, § 301, 1886 N.Y. Laws 39, 41. Thanks to John Noyes for this research and citation, and to Amy Kurtz Lansing for contributing contextual passages for this blog.

[2] Obituary, New York Herald, September 23, 1918, p. 4.