By George Willauer

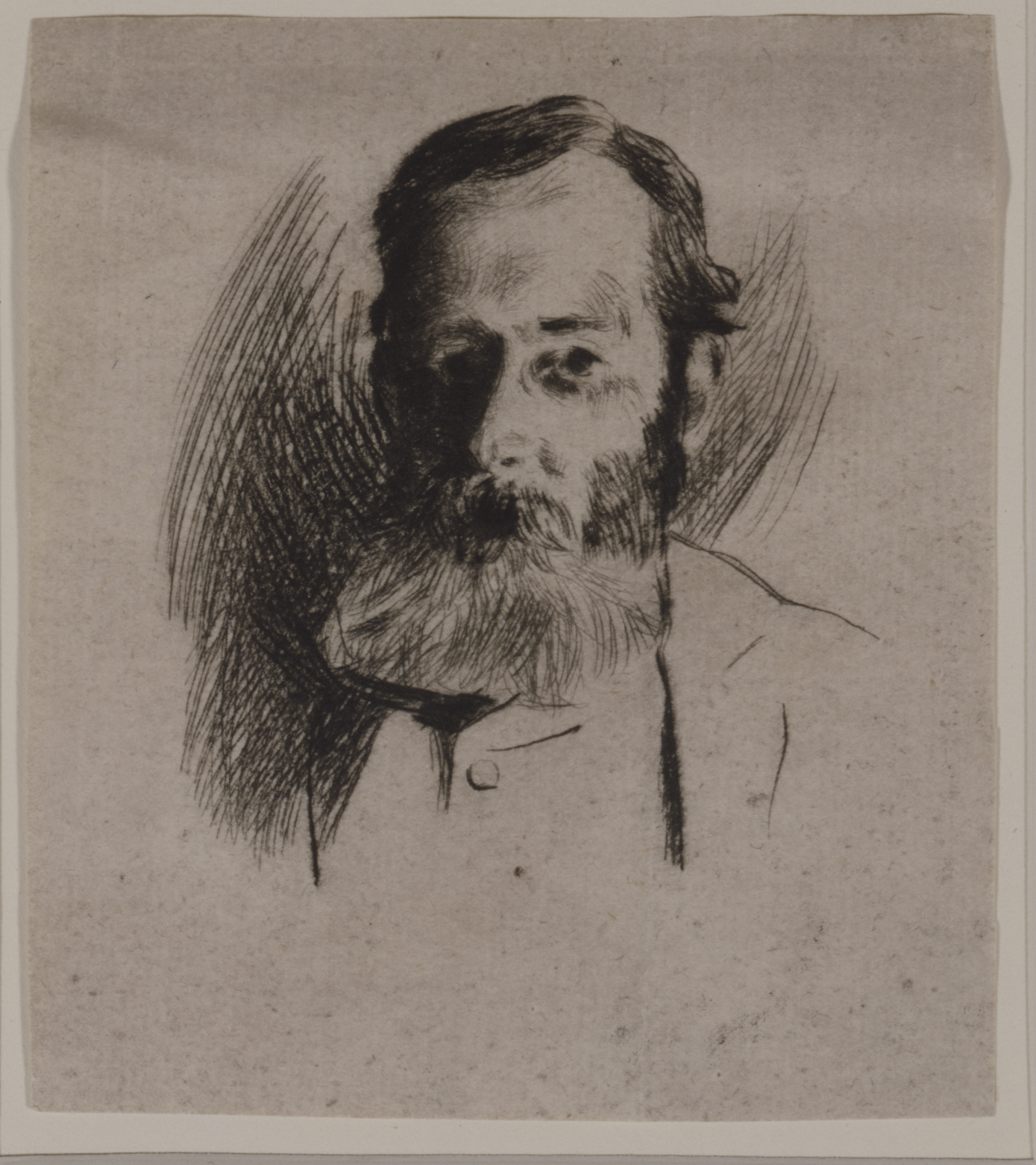

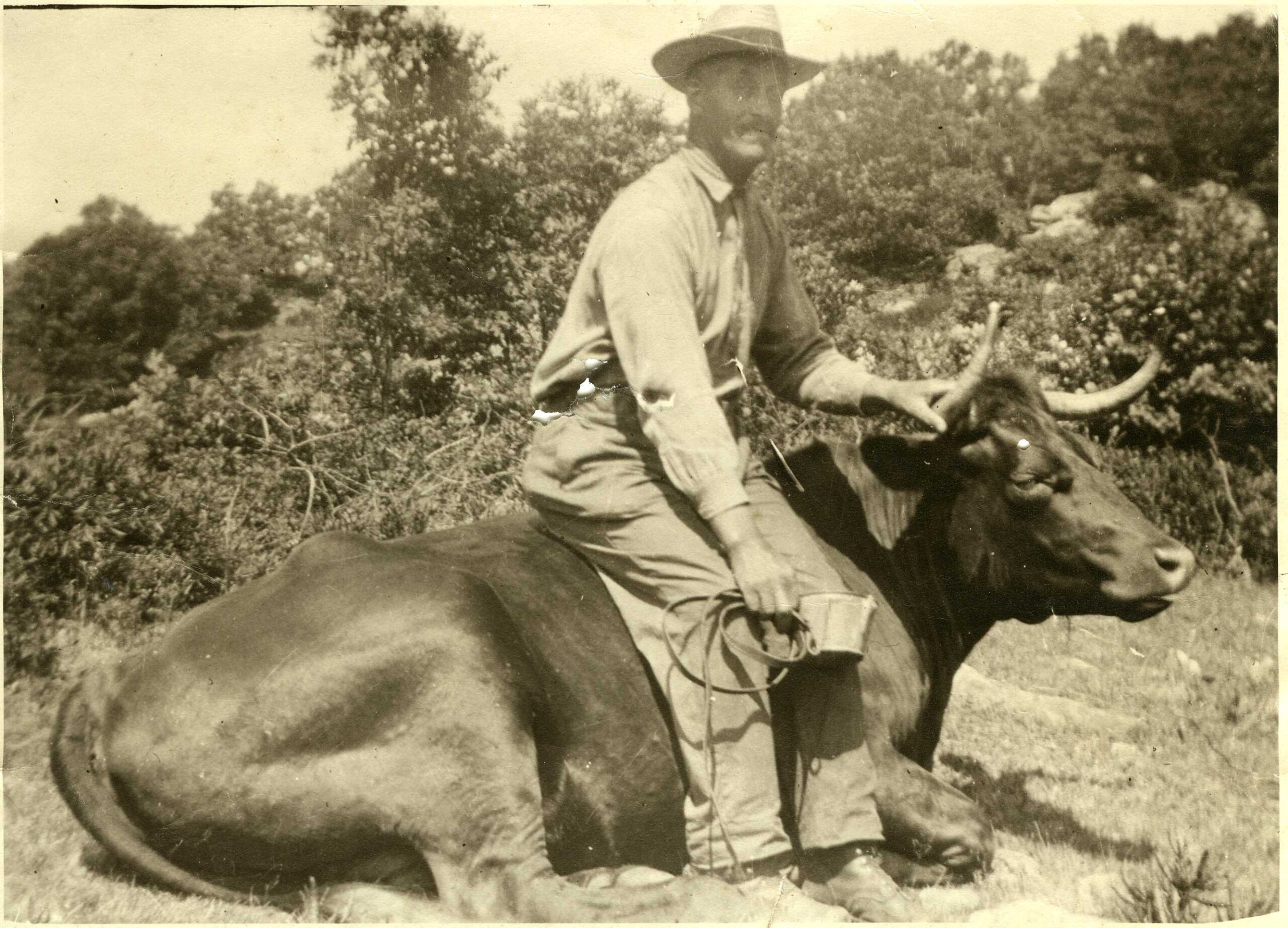

Featured Image: Joseph Caples on an Ox. Collection of the Lyme Public Hall

Joseph Caples, a descendant of Native American and African American slaves, lived from 1873 to 1954 on Gungy Road in Lyme. Today, in this time of civil unrest and systemic racism, we wonder what was it like for Joseph Caples to live in Lyme. How did he make his living? Was he discriminated against or accepted? Was he content living in a predominately white town?

In the Local History Archives of the Lyme Public Hall are nine quarto-size daybooks recorded by Joseph Caples. Although some years are missing, extant volumes cover the years between 1917 and 1930. The Archives also contain a typescript of the original handwritten Memoir of Joseph A. Caples, which he wrote in 1949, a few years before his death.

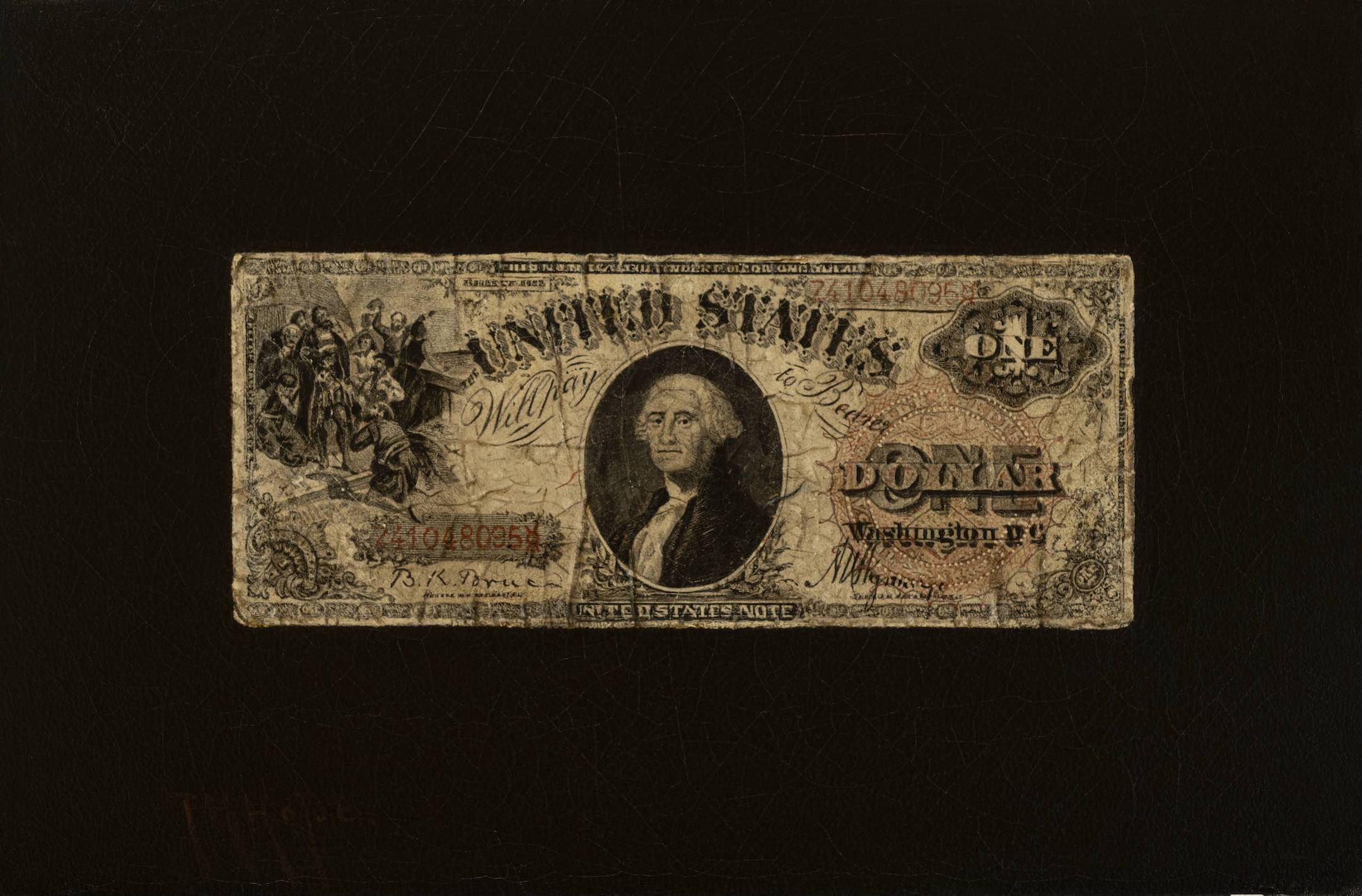

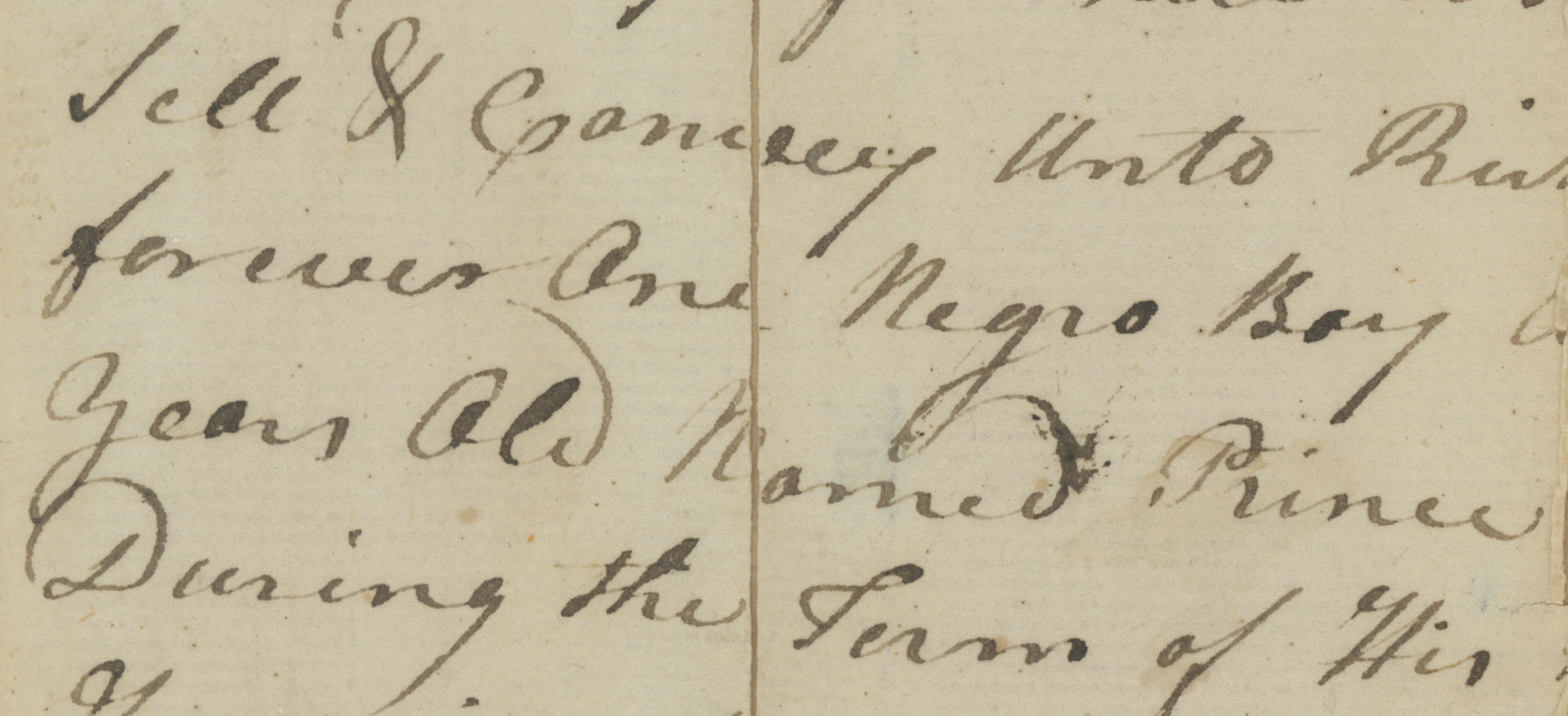

Caples begins his memoir in 1949 by tracing his roots back to slavery. He writes: “I am starting this little Memoir from the way back in the Middle 1700’s when there was a serf-lad known only as Cuff, who grew to manhood – raised a large family of about Ten children, and subsequently bought his time. Adopted the name of Condol and with the support of his family Acquired quite a bit of property on both sides of this road known as the Gungy road.”

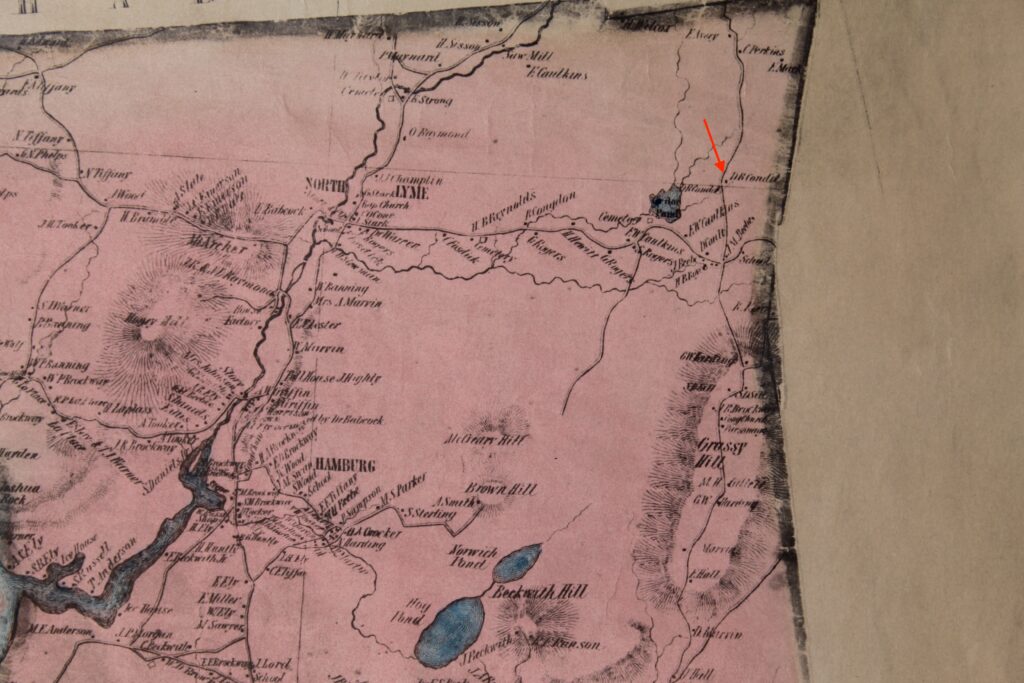

Map of Lyme showing Joseph Caples’s home on Gungy Road. Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum (LHSA)

Census records in Rhode Island describe Cuff as the son of an “Indian man and an unknown woman” whose parents were “likely of Nehantic, Narragansett, and Pequot Sachem bloodlines.” After his enslavement by Captain Stephen Smith of Lyme, Cuff bought his freedom from subsequent owners in 1790 and in 1794 began purchasing land in Lyme. Joseph Caples was Cuff’s great grandson. On his mother’s side he descended from Prince Crosley, one of Matthew Griswold’s slaves whose mother Eunice Crosley was a Native American.

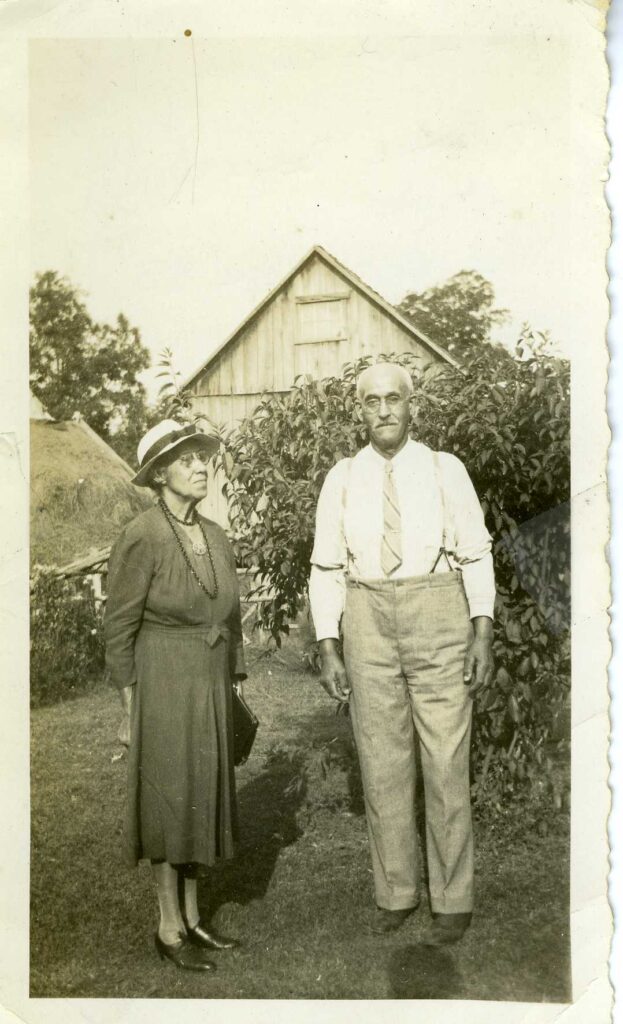

In 1913 Caples married Martha Bogue, who was born in Norwich in 1868 and died in 1952. The couple lived together childless in the same house on Gungy Road where Joseph was born until his death. According to different census records Martha or “Mattie” is identified as an Indian, as black, and as a mulatto.

The complexity of the Caples family lineage is reflected in the United States Census records. The designations vary from decade to decade, sometimes showing the word “black,” sometimes “mulatto,” sometimes “negro,” but not “Native American.” Specifically, the Lyme census for 1900 includes thirteen “blacks,” including four members of the Caples family. In the census for 1910 five members of the Caples family are listed as “mulatto,” along with seven other “mulattos” and one “black.” Ironically, the 1920 census lists Joseph and Martha Caples and one other resident as “Mexican,” and also lists six “mulattos.” Then in 1930 Joseph and Martha are listed as “negroes,” as are six others. Similarly in the census of 1940, they are listed as “negroes,” in addition to thirteen others.

In his writings Caples gives little information about his Native American and African American slave heritage and how he saw himself in relation to it, but he wrote abundantly about his daily life and his relation to the town in which he lived. The entry for each day, legibly written, fills nine to twelve lines of the provided space and almost invariably covers the same topics: the weather, Caples’s activities, his wife’s activities, the number of callers, if any, and the number of vehicles passing by the house. One entry states, “one more car each way”; another, “no callers, no mail, no news.”

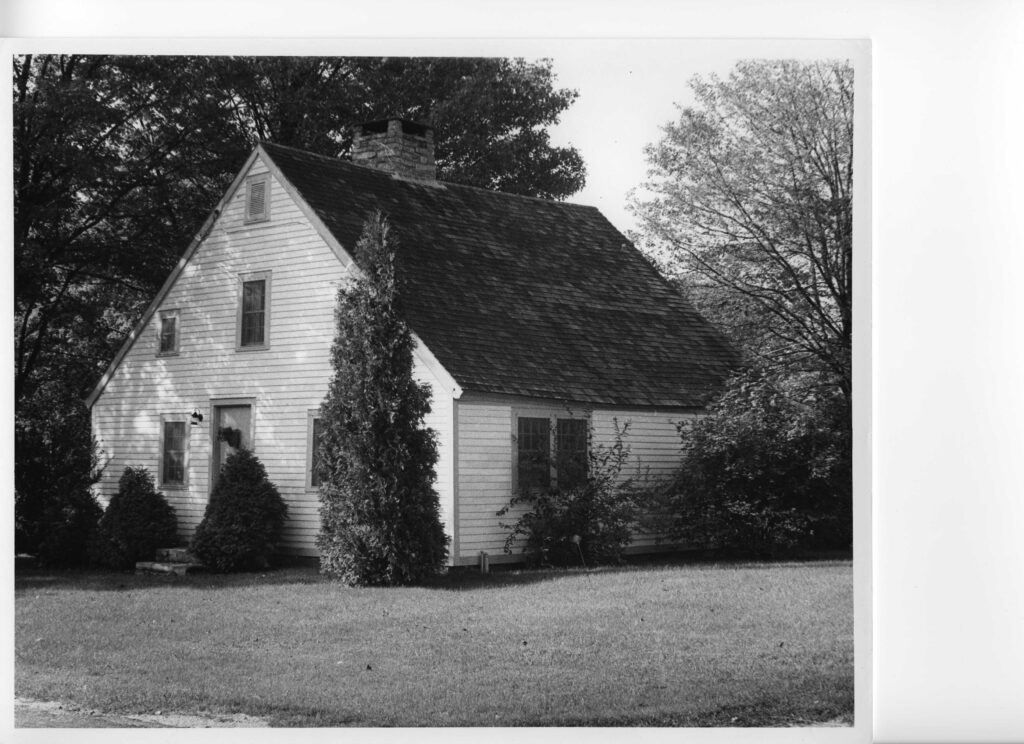

Joseph Caples’ birthplace home on Gungy Rd. Lyme, CT. Collection of the Lyme Public Hall

Although Caples made little specific reference to himself in his diaries, on September 9, l913, he wrote he had “no complaints,” and on March 19, 1927, he wrote that he had been “laid up with a cold,” and unable to write for a week. In general, however, Caples devoted his energies to the cultivation of the land he had inherited and to his means of subsistence. He kept a substantial vegetable garden, in the spring planting potatoes, beans, corn, tomatoes, radishes, lettuce, and assorted root vegetables, in the summer tending them, and harvesting them in the fall. Caples also kept fruit trees. Livestock provided another source of food and income. On May 17, 1918, he listed all of his livestock: 1 horse aged 12, 1 pair oxen, 1 cow, 4 calves, 4 sheep, 2 lambs, 1 hen, 1 rooster, and 1 cat

Caples also kept a flock of sheep and bred them for meat, wool, and milk. On October 26, 1931, he sold 130 pounds of wool for $19.50. His primary relation to sheep, however, was in sheering them for money. Chopping, splitting, and hauling wood provided an additional source of income, and he kept busy trapping skunks, foxes, weasels, linx, and mink, whose pelts he sold for profit.

In addition, Caples scoured his land for walnuts, butternuts, ginseng plants, snakeroot, and arbutus. Ginseng, recognized for its therapeutic value thousands of years ago, was found in uncultivated parts of North America where it was processed and used for relief from mental and physical distress.

In his memoir Caples names twenty or more herbs of medicinal value as well as the Quassia Cup. He writes that the “bitter cup” is still in his possession and “still makes its own Medicine without drugs, as it did 100 years or more ago (as a tonic).” Popular in the nineteenth century, the Quassia Cup was made from the wood of a small tropical shrub from Jamaica. Also known as bitter wood, it contains quassia, a bitter substance used in the treatment of fever and digestive problems, among others.

Perhaps Caples’s most lucrative enterprise, however, was the collection of branches of the witch hazel bush. These he loaded in his ox drawn wagon and delivered to a mill in Sterling City, a section of Lyme. In later years he delivered them to Hamburg. There they were shipped across the Connecticut River to Essex and the Dickinson distillery where they were macerated and distilled. Still popular today, though made chemically, witch hazel is sold as a remedy for psoriasis and eczema, and as an aftershave.

Joseph Caples and Martha Bogue Caples ca. 1950. Collection of the Lyme Public Hall

Caples’s marriage to Mattie was central to his livelihood and happiness. Appropriately, he devotes considerable space in the diaries to Mattie and seems to enjoy describing her independence, including her visits to neighbors near and far, usually on foot.

With his efforts the couple kept up with the times. At some point their house was wired for electricity, and in1928 Joseph installed a telephone, popular with neighbors who didn’t yet have one. In 1929 he began a subscription to the Norwich Bulletin, the same year he received his first Sears Roebuck catalog and saw his first “talking movie.” When there was free time, the couple enjoyed working on puzzles and playing games of pinochle and “500.” Caples was also a reader, relying on books from the “Hamburg library” and from Alice Rogers, a friend who kept a bookstore and lending library on the main street in Old Lyme.

Despite the remoteness of his dwelling, Caples was involved with many parts of his community. Demonstrating his civic commitment, one evening he joined a neighbor in Hamburg to “talk over school matters.” On another occasion he voted at a town meeting. Going to church services at the Grassy Hill church and at the church in Hamburg with Mattie was another way he participated in the life of the town. At one time Joseph was treasurer of the Grassy Hill church and Mattie was a reader.

Together the couple delighted in invitations to the houses of their friends. More than once Caples reported having “a very fine time” at dinner parties, dances, and a program “for entertainment” at the school house. A Halloween party kept them out until 1 a.m. and a dance until 3 a.m. Once, after attending a “salt water party,” presumably at the beach, they “sang all the way home.” On the couple’s fifth wedding anniversary twenty friends celebrated with them and gave them a “wooden shower,” perhaps made of wood, a local commodity, and readily available and inexpensive.

Mobility is essential to friendship, but the Caples never owned an automobile. Town records from 1915 show there were twenty-three cars in Lyme that year, but in 1917 Joseph bought a two-seated wagon for $15 from Warren Stark. Thereafter he relied solely on his horse-drawn carriage, or the good will of his neighbors. Impecuniosity? Thrift? Eccentricity? We may never know, but we can imagine that while neighbors could drive to New London in less than an hour, Caples walked to Laysville to get “a car,” presumably a trolley, when he went to New London. Another entry reports that he and Mattie left home at 4:30 a.m., arrived for business purposes at Norwich at 8, and didn’t get home until 10 p.m.

Joseph and Mattie loved their home and liked to share it with many friends. One year forty-five attended a surprise birthday party for Joseph, and another year there were fourteen guests for the Thanksgiving meal with music until 10 p.m. Further evidence of the Caples’s social life is the number and variety of friends mentioned in Joseph’s diaries. Sometimes the names of visitors fill a day’s entry. Especially intriguing are names of “Callers” that appear at the end of daily entries. Many of them came from as far away as Chicopee and Williamstown. Of particular interest are friends from Lyme and Old Lyme. Alice Rogers provided them with books, and Rev. Dixon Hoag, minister of the First Congregational Church of Old Lyme, presided at the funeral services of both Joseph and Mattie.

Gertrude Whiting, Portrait of Alice Rogers, 1926. Oil on canvas. Old Lyme Memorial Town Hall

Other friends were generous financially, suggesting that the Caples lived marginally, despite their self-sufficiency. These friends included Margaret Cooper, an artist, and her husband. Several times, it is thought, she painted Joseph with his oxen against a barnyard setting. Two of those paintings are displayed in the Lyme Public Library, and others by Cooper are in the collection of the Florence Griswold Museum. The Caples were also grateful to “Dr. and Mrs. Edmund R.P. Janvrin and daughters Natalie and Mary of N.Y. City, and their contributions to our welfare and great comfort in our declining years.” In later years Natalie Janvrin married Grafton Wiggins, son of Lyme Colony artist Carleton Wiggins.

Margaret Cooper, Painting thought to depict Joseph Caples. Oil on canvas. Lyme Public Library.

A reading of Joseph Caples’s diaries and associated documents produces a colorful portrait of a remarkable man. Relying on inherited land, he created a model of sustainability. Evidence of his commitment to public service, the church, and the warm embrace of countless individuals from near and far suggests a life lived fully and happily, absent of discrimination. Could we say that Joseph Caples symbolizes the ideal Yankee? Together with Mattie might we consider them iconic figures like those in Grant Wood’s painting “American Gothic”? In their heritage and lifestyle is there a lesson for us today?

—————————————

Sources:

Brooks, Graham. History of the Indians of Connecticut (Hamden, 1964).

Brown, Barbara W. and Rose, James. Black Roots in Southeastern Connecticut, 1650-1900 (New London, 2001).

Lampos, Jim and Pearson, Michaele. Hidden History of Old Lyme, Lyme & East Lyme (Charleston, 2020).

Lauber, Almon Wheeler. Indian Slavery in Colonial Times within the Present Limits of the United States” (New York, 1913).

Newell, Margaret Ellen Newell. Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of Slavery (Ithaca, 1962).

Welch, Vicki. And They Were Related, Too (Xlibris Corp., 2006).