by Carolyn Wakeman

Feature Photo (above): Edna Leighton Tyler, Katharine Ludington in her garden, 1925. LHSA

The gardens that surrounded Old Lyme’s Meetinghouse for more than a century trace the changing needs, tastes, and financial circumstances of a prominent local family. A series of images taken in 1925 by photographer Edna Leighton Tyler (1879–1970) captures the sweeping lawns and luxuriant flowerbeds on Katharine Ludington’s estate. But the land behind her elegant Colonial Revival home had once served more practical uses.

Grandmother Noyes’ Gardens

Phoebe Griffin Noyes, Portrait of Her Children, ca. 1845. Photocopy courtesy Ludington Family Collection

Phoebe Griffin Noyes, Portrait of Her Children, ca. 1845. Photocopy courtesy Ludington Family Collection

Phoebe Griffin Noyes (1797–1875) provides the earliest view of the grounds that her son-in-law Charles H. Ludington (1825–1910), a wealthy New York businessman, would later transform into a fashionable summer residence. For a group portrait of her five children painted ca. 1845, she chose as backdrop the well near the side door of her century-old home and included the fenced rear field.

But having studied miniature portrait painting in New York for a decade, Mrs. Noyes chose to embellish the landscape in accordance with the fashion of her day. An imagined river scene “improved” the ordinary details of her dooryard. “Grandmother has ‘arranged’ her composition somewhat by bringing the Connecticut River into the picture,” Katharine Ludington (1869–1953) wrote in an affectionate family memoir privately published in 1928.[1]

Charles Ludington house, ca. 1890. Courtesy First Congregational Church of Old Lyme

Edna Leighton Tyler, Charles Ludington house, 1925. LHSA

Edna Leighton Tyler, Charles Ludington house, 1925. LHSA

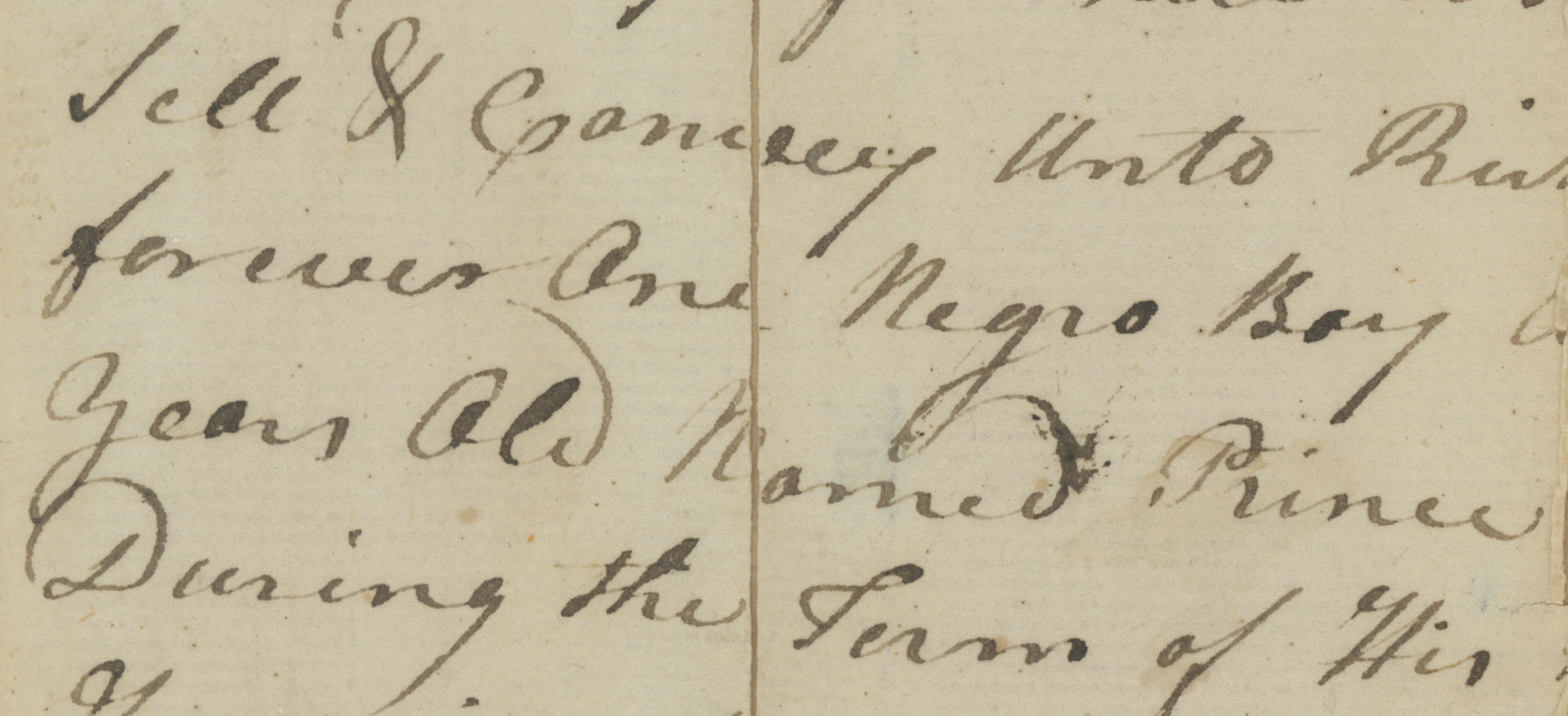

Miss Ludington’s account Lyme—and Our Family details the transition from what had been ”a kind of farm” in her grandfather’s day to the stylish country “place” that her father designed. “What is now the south lawn was a flower garden, with a fence around it,” Katharine recalled. “Where the ‘circle’ now is, the old barn stood, with orchards to the right and left of it. . . .The present upper garden was then a mixture of fruit, vegetables and flowers.”[2]

Daniel Rogers Noyes (1793–1877) did many of the farm chores himself, planting peas and potatoes, feeding the pigs, cows, and chickens, or pruning the orchards when he was not at work in his general store across the street. Family letters remarked on the quality of his pear crop in autumn and the peach pickles, apple jelly, and quince marmalade that Grandmother Noyes had “put away.” From a young age their daughters tended garden plots of their own. “The flowers in our garden are most of them in blossom,” Julia Noyes (1883-1885), age ten, wrote to her older sister in 1843. “I planted all my seeds as much as a month ago and most all of them have come up.”[3]

George Henry Yewell, Phoebe Griffin Noyes (detail), ca. 1898.

Katharine recalled from childhood the ice house, the smoke house, the grape arbor, and the “small trellis covered with Virginia Creeper” outside the front door. But what lingered most vividly in her memory was the “smell of flowers and outdoor things that came in through the windows—lilacs, syringa blossoms, the smoke tree in the corner of the front yard, honeysuckle, hay.” Her attachment to Lyme derived in no small part from fond memories of her grandmother’s garden, which “had flowers and many flowering shrubs, and there were beds either side of the path to the front door, with box bushes, bleeding heart, wygelia and other favorites.”[4]

Charles H. Ludington’s Grounds

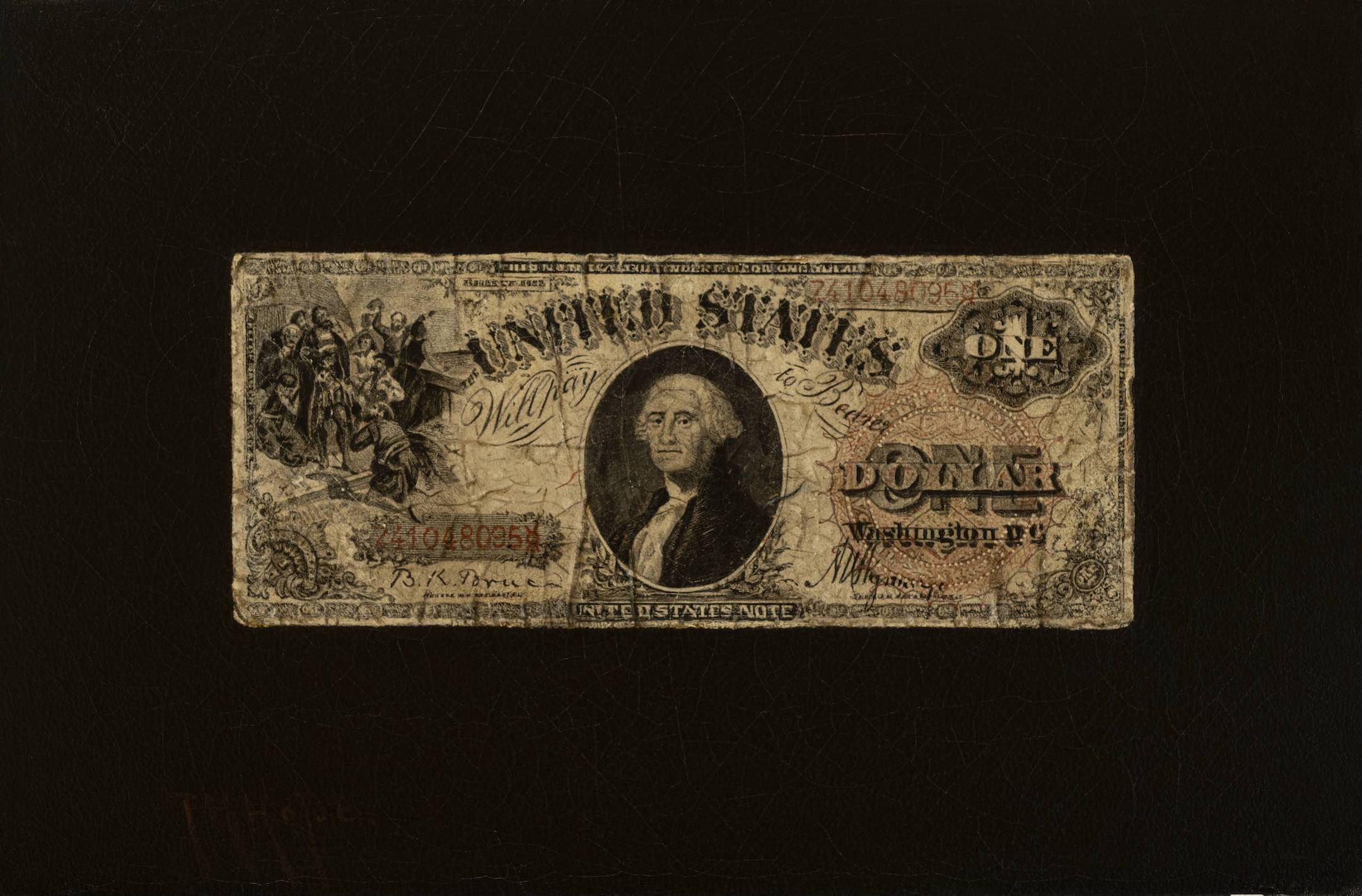

“Strawberries—Soil, Culture, and Varieties,” The Horticulturist, July 1867

“Strawberries—Soil, Culture, and Varieties,” The Horticulturist, July 1867

The columnist for the local Sound Breeze newspaper recommended in April 1889 that townspeople make use of the twenty-seven handsomely bound volumes of The Horticulturist recently donated to the local library by Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury (1823–1917), daughter of the Ludingtons’ neighbor Charles J. McCurdy (1797–1891). “There is shown in Lyme much interest in the decoration of private grounds,” the article noted, and “much valuable information may be obtained from these books.”[5]

Charles J. McCurdy house, ca. 1890. LHSA

Charles J. McCurdy house, ca. 1890. LHSA

Judge McCurdy, by then 82, had been improving his private grounds for more than two decades. “The south side of the house as far as the well is nearly filled up & graded & may now be seeded & manured & smoothed over at any time,” he wrote to his daughter Evelyn in 1867. “The seeds in the hot beds are doing well & the asparagus is coming up. The strawberries are looking vigorous.”[6] Like Richard Griswold who installed ornamental gardens and a greenhouse on his Boxwood estate nearby on Lyme Street, Katharine’s father took a keen interest in horticulture and landscaping. In 1878 after the death of his wife’s parents, he began making “improvements in the place according to the ideas of his day.”[7]

Mr. Ludington’s hot beds were well established by 1883. Every two days during the winter months, after Katharine and her family had settled back into their Madison Avenue townhouse, he sent detailed instructions by postal card to his caretaker in Lyme. Out-of-season flowers and vegetables grown on his country estate and shipped to the city by rail brought pleasure and pride. Frances Jane Lord (1810–1888), his wife’s elderly aunt, wrote in early December to advise that the gardener “has thus far been very faithful to your hot beds” but that the “large pile of celery from twenty to forty heads” stacked in the barn would freeze if not shipped the next day.[8]

Ludington estate, circle with ornamental planting, ca. 1902. LHSA

Ludington estate, circle with ornamental planting, ca. 1902. LHSA

A decade later Mr. Ludington hired New York architect Henry Rutgers Marshall (1852–1927) to design a replacement for his aging summer dwelling. By then he had turned the flowerbeds on the south into a lawn, pushed back the barn to allow for a driveway, and developed the lower garden out of swampy land. The recently added front section of the house where the maids had slept under the eaves would be hauled by ox team to Mrs. Salisbury’s property nearby for use as a high school, while the rear section, over two hundred years old, would be pulled down.[9]

In June a New York real estate inventory noted: “Henry Rutgers Marshall has drawn plans for a three-story frame colonial dwelling, 62×65, the interior to be in the colonial style also. C.H. Ludington is the owner and $20,000 the approximate cost.”[10] A student of Henry Hobson Richardson (1838–1886) and later head of the American Institute of Architects, Mr. Marshall was related to the Ludington family by marriage and had already worked in Lyme. Six years earlier he designed elaborate renovations for the Meetinghouse next door.[11]

Ludington estate, upper garden, ca. 1902. LHSA

Ludington estate, upper garden, ca. 1902. LHSA

Ludington estate, rear garden showing greenhouse and barn, ca. 1902. LHSA

Ludington estate, rear garden showing greenhouse and barn, ca. 1902. LHSA

Charles H. Ludington, Whitefield rock, ca. 1902. LHSA

Charles H. Ludington, Whitefield rock, ca. 1902. LHSA

The “decoration” of the Ludingtons’ grounds embodied the “green, private and peaceful” ideal of the late 19th-century country place.[12] Two sets of photographs display its curving paths, clustered shrubs, and massed herbaceous borders. A large family album, professionally prepared, documents the ornamental plantings on the south lawn, the profusion of flowers in the upper garden, the handsome rear barn, and the fabled rock where British evangelist Rev. George Whitefield (1714–1770) preached when he passed through Lyme.

Ludington estate, south lawn. Hand-colored photograph. LHSA

Ludington estate, south lawn. Hand-colored photograph. LHSA

Ludington estate, upper garden. Hand-colored photograph. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection

Ludington estate, upper garden. Hand-colored photograph. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection

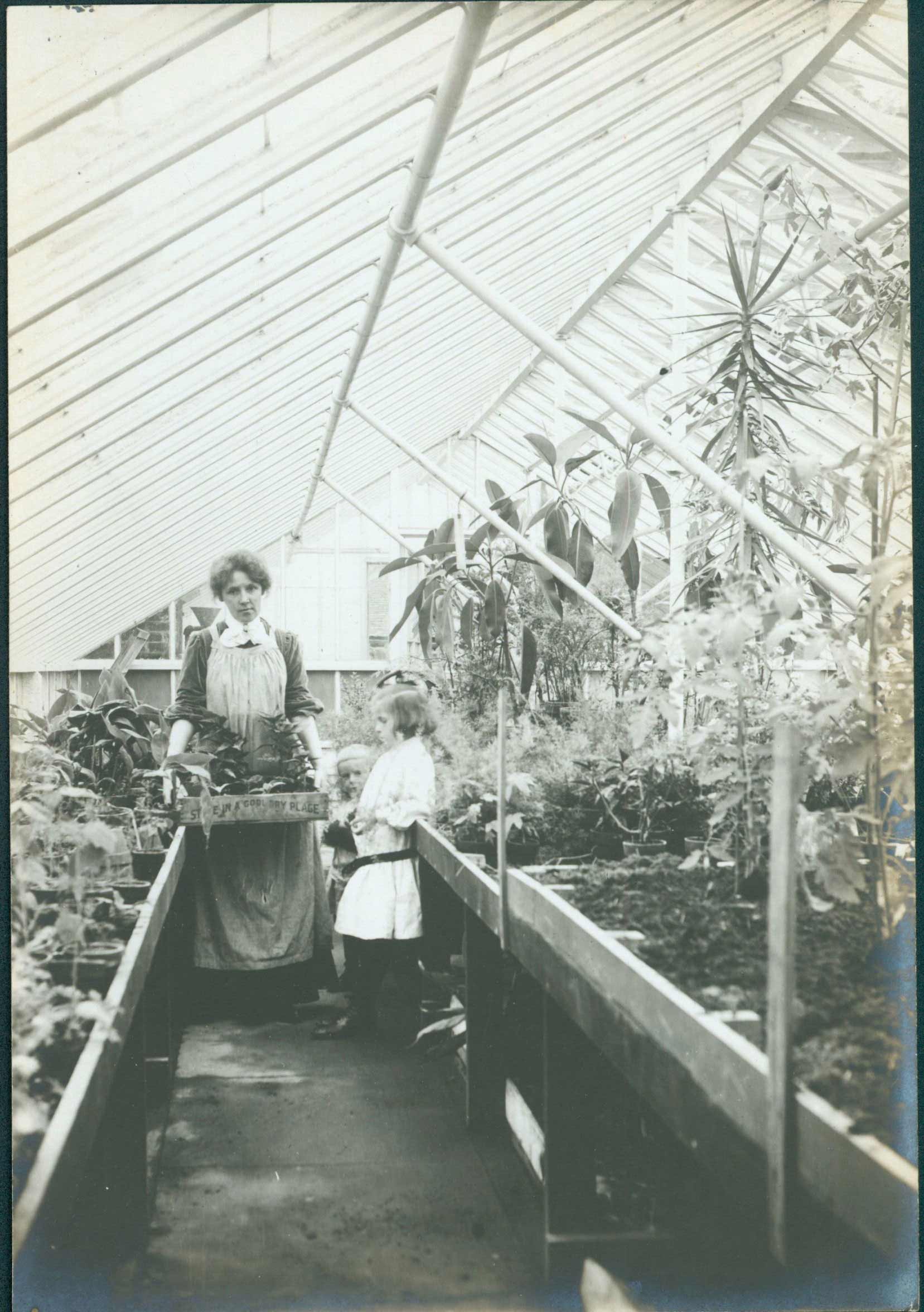

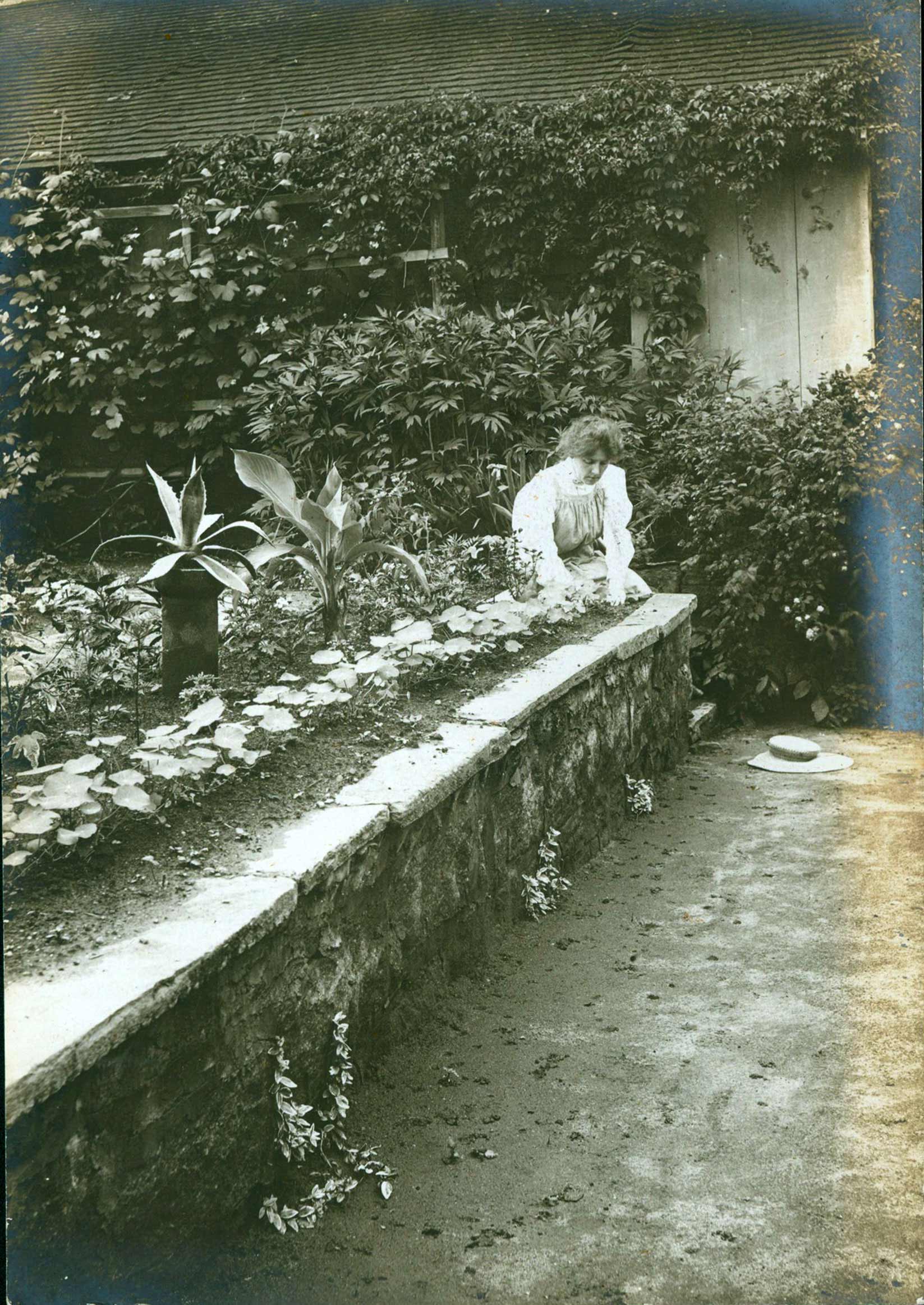

A second series of photographs not only conveys the artistry of the grounds but also hints at the labor they required. Two views have been colored by hand to display the vibrant hues of poppies and old-fashioned perennials amid the depths of summer green. Other images in black and white show bedding plants in the greenhouse, landscaping along a rock wall, and strawberries protected by white netting.

Protecting the strawberry beds. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection

Protecting the strawberry beds. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection

Bedding plants in the greenhouse. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection

Bedding plants in the greenhouse. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection

The New London Day praised the Ludingtons’ “fine old estate” in a 1904 article commending Lyme’s scenic beauty: “In the rear of the house is a beautiful formal garden, with box-bordered paths, and beds of red and pink geraniums and lobelia, borders of golden and hardy marigolds in masses of gold and clumps of phlox and scarlet carmas. At the end of the garden is a sunken terrace, and here in a corner, half hidden by shrubbery is the rock on which Whitfield preached.”[13]

Landscaping along a rock wall. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection

Landscaping along a rock wall. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection

Miss Ludington’s Flowers

The Ludingtons’ grounds drew the attention of landscape artist Matilda Browne (1869–1947) when she spent summers at the Old Lyme Inn nearby on Ferry Road. In Miss Ludington’s Garden she captures the varied shapes, textures, and colors of a boxwood-bordered bed of pink, white, and lavender summer blooms. The viewer’s gaze travels across the flowers massed in the upper garden to the comforting simplicity of the gardener’s white cottage bathed in the warm rays of an early morning sun.[14]

Matilda Browne, Miss Ludington’s Garden, ca. 1914. Private collection

Matilda Browne, Miss Ludington’s Garden, ca. 1914. Private collection

It fell to Miss Ludington who inherited her parents’ home to complete the repair and replanting that her father began after fire destroyed the beloved Meetinghouse in early July 1907. The midnight blaze charred their home, destroyed the adjacent trees and shrubs, and left the gardens “half ruined.” Ten days later Katharine wrote to a cousin: “The flower garden is gone for this summer, but the south side of the place looks just as usual.”[15] Matilda Browne’s canvas, painted ca. 1914, celebrates the garden’s restoration.

Ludington estate, gardener’s cottage. Courtesy First Congregational Church of Old Lyme

Ludington estate, gardener’s cottage. Courtesy First Congregational Church of Old Lyme

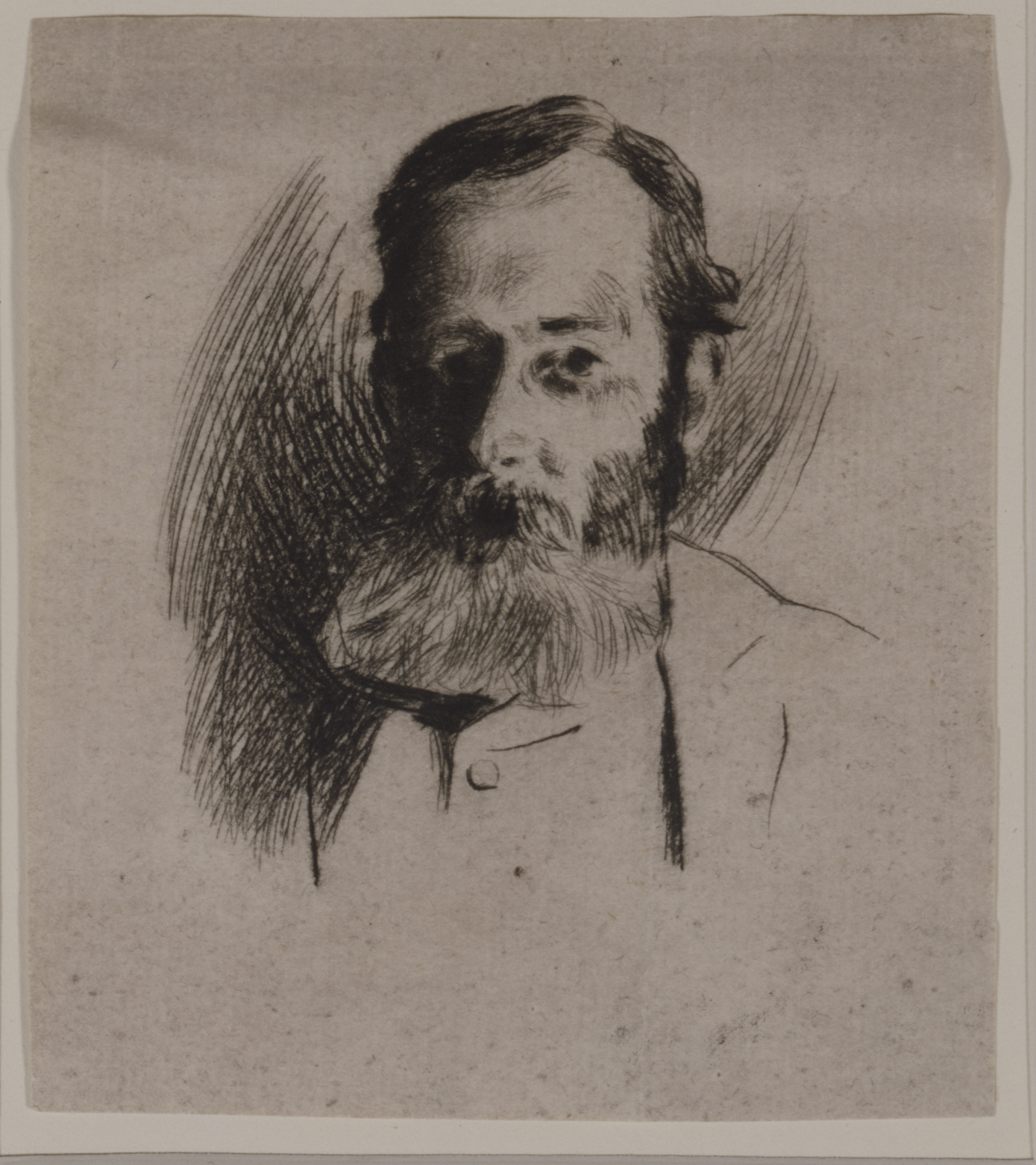

Encouraged from childhood to follow in the artistic footsteps of her grandmother, Katharine studied at the Art Students League and worked as a professional portrait painter for two decades. Her love of flowers is evident in a series of early watercolor studies from her years at Miss Porter’s School in Farmington where she began her study of portraiture with art teacher Robert Brandegee (1849–1922). While working in his New York studio in 1889, she completed the portrait of her mother Josephine Noyes Ludington (1839–1908) that hangs today in the public library named for her grandmother Phoebe Griffin Noyes.[16]

Katharine Ludington with flowers, ca. 1892. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection

Katharine Ludington with flowers, ca. 1892. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection

World War I led Miss Ludington to set aside her artistic career and focus her attention on urgent social and political problems. “I think I told you that I had taken the chairmanship of the Suffrage work in New London county,” she wrote to her cousin in 1916.[17] Four years later as head of the Connecticut Women’s Suffrage League she led the fierce struggle in Hartford for a woman’s right to vote. Over the next forty years as national vice-president of the League of Women Voters and a tireless advocate for international peace, she traveled extensively. Always she returned gratefully to the beauty and serenity of her country home.

Katharine Ludington, Roses. Watercolor and gouache on paper, 1881. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection.

Katharine Ludington, Roses. Watercolor and gouache on paper, 1881. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection.

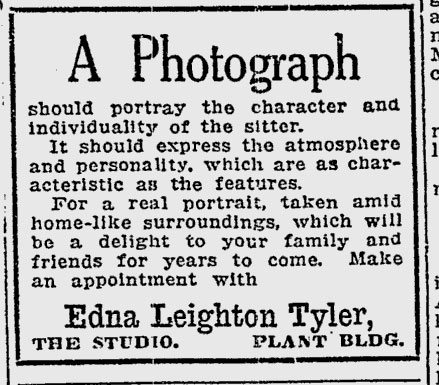

Edna Leighton Tyler, a New London photographer with a studio on State Street, shared an interest in portraiture, a commitment to women’s emancipation, and a love of gardens. [18] A portfolio of signed, sepia-toned studies of the house and grounds that Katharine commissioned in 1925 conveys an almost dream-like aura of elegance and seclusion. Rather than crisply defining the details of architecture and landscape, Miss Tyler achieved a hazy pictorial quality by blurring the outlines of trees and shrubs and allowing the church steeple rising above the elms to recede softly into the distance.[19]

Edna Leighton Tyler, studio advertisement, 1917

Edna Leighton Tyler, Ludington estate, garden path, 1925. LHSA

Edna Leighton Tyler, Ludington estate, garden path, 1925. LHSA

Edna Leighton Tyler, Ludington house front entrance, showing church steeple, 1925. LHSA

The grounds changed little during Miss Ludington’s lifetime. She took pride and comfort throughout her years of pubic service in maintaining the old-fashioned flowers that Grandmother Noyes had favored and the elegant landscaping that her father designed. But she made one addition to the upper garden. In about 1938 she positioned the ornamental bronze sculpture of a fawn created by her niece Lydia Williams Rotch (1910-2005) on a central stone pedestal where it could be viewed from the street through the arching frame of a vine-covered arbor.

Lydia Williams Rotch, The Fawn, ca. 1938. Artist’s replica, ca. 1980, Ludington Family Collection

[1] Katharine Ludington, Lyme–and Our Family (1928), p. 26.

[2]Ludington, pp. 89, 25.

[3] Ludington, p. 18; Julia Lord Noyes to Caroline Lydia Noyes, May 17, 1843. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection.

[4] Ludington, pp. 13-14.

[5] The Sound Breeze, April 2, 1889. LHSA.

[6] Charles J. McCurdy to Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury, April 21, 1867. Courtesy Old Lyme Historical Society.

[7] Ludington, p. 26.

[8] Frances Jane Lord to Charles H. Ludington, December 1, 1883. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection. Patricia M. Tice notes that constructing and heating greenhouses and hot beds to grow exotic and expensive types of produce out of season signaled social and economic status. See Gardening in America: 1830-1910 (Rochester, 1984), p. 51.

[9] Ludington, pp. 22, 19.

[10] Index to the Record and Guide for New York Conveyances and Projected Buildings, Vol. 51, January to June, 1893, p. 494.

[11] Mr. Marshall was said to undertake “the improvements in the interior” of the Meetinghouse as “a labor of love,” and Mr. Ludington contributed a handsome set of carved mahogany pulpit furniture to complete the refurbishing. The New-York Tribune, October 26, 1887, courtesy First Congregational Church of Old Lyme. That same year H. H. Richardson designed New London’s Union Railroad Station.

[12] Mariana van Rensselaer, Century Magazine (1897), cited in Lisa N. Peters, ed., Visions of Home: American Impressionist Images of Suburban Leisure and Country Comfort (Hanover 1997), p. 12.

[13] “Old Lyme, The Beautiful; Resort of Many Artists,” The New London Day, August 18, 1904.

[14] Lyme colony artists frequently chose country homes and gardens as their subject, and Matilda Browne used a similar composition for her painting In Voorhees’ Garden (ca. 1914). See the thoughtful discussion in May Brawley Hill, “’For the Scent of Present Fragrance and the Perfume of Olden Times’: The Domestic Garden in American Impressionist Painting,” in Peters, pp. 53-78.

[15] Katharine Ludington to Arthur Ludington, July 4, 1907; Katharine Ludington to Helen Gilman Brown, July 14, 1907. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection.

[16] Katharine Ludington to Helen Gilman Brown, March 18, 1889. Gilman-Brown Collection, New York Public Library.

[17] Katharine Ludington to Helen Gilman Brown, July 2, 1916. Gilman-Brown Collection, New York Public Library.

[18] Edna Tyler established the New London branch of the League of Women Voters. See Tricia Royston, “New Exhibit–‘Votes for Women,’” New London County Historical Society Newsletter (June 2010); Carol Kimball, The New London Day, November 8, 1990.

[19] Miss Tyler used the same technique in 1933 for a series of garden photographs taken at the Harkness estate in Waterford. See Alan Emmet, So Fine a Prospect: Historic New England Gardens (Hanover, 1996), pp. 223, 226.