Carolyn Wakeman

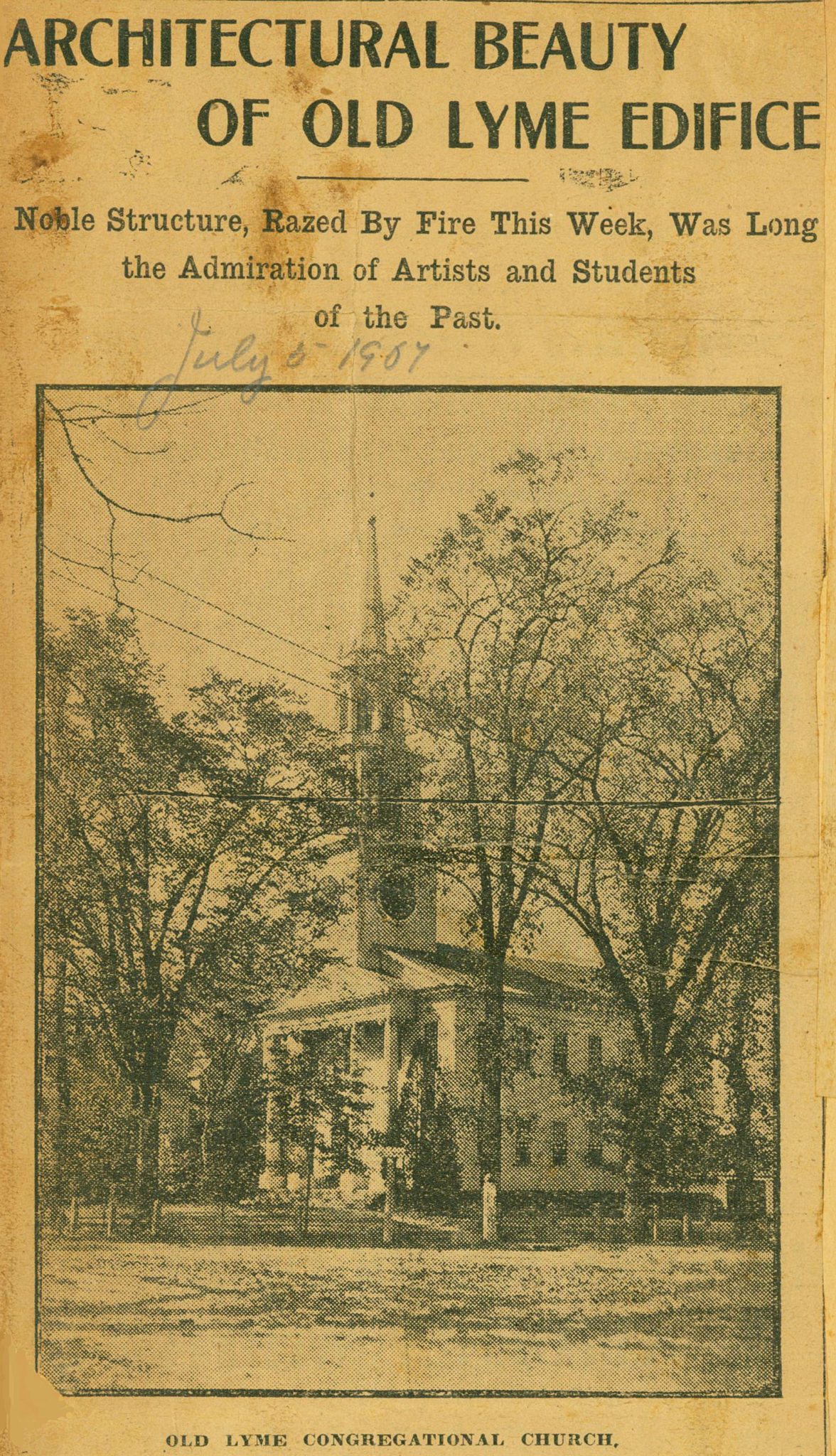

Featured Photo: First Congregational Church, Old Lyme, ca. 1900. LHSA

The Independence Day holiday in 1907 passed without celebration in Old Lyme. Ashes still smoldered from the fire that demolished the Meetinghouse on July 3, and the community united in a sense of shared loss. But when the newly arrived minister proposed replacing the elegant white clapboard structure that had graced the village for almost a century with an “up-to-date” red brick church, controversy flared.

Old Lyme Church, The Day, July 5, 1907. Courtesy First Congregational Church of Old Lyme

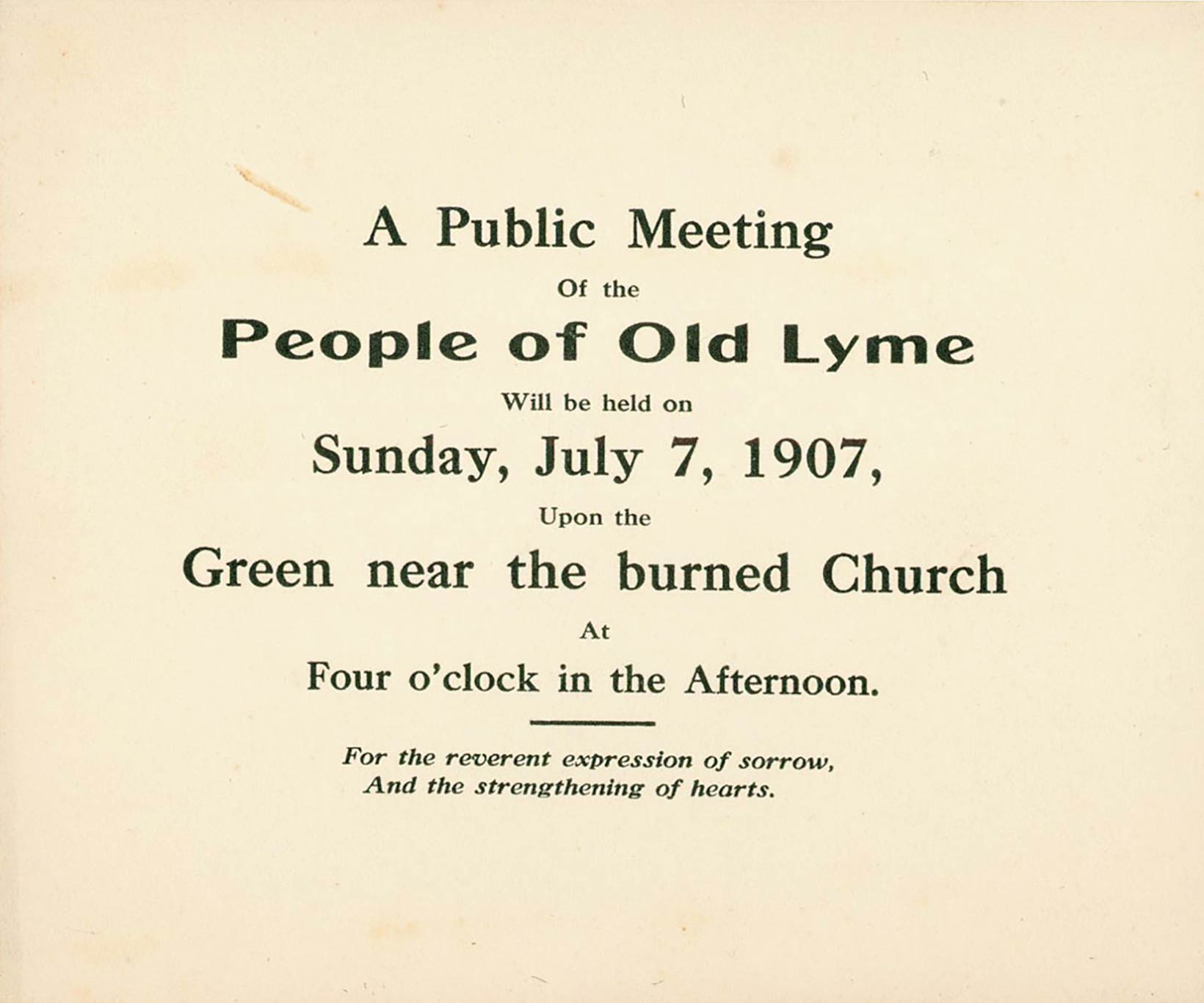

“The people of Lyme and for miles around turned out as if moved by mutual sympathy,” reported The Deep River New Era after a public meeting on July 7 beside the ruins.[1] Judge Walter C. Noyes (1865–1926), a descendant of the town’s first minister, spoke for the community: “It was not as a fine building that the old church was most dear to us,” he said. “It entered into our inner-most lives.” Following his remarks, Frank Vincent Du Mond (1865–1961), a leading member of the Lyme art colony, “voiced the sorrow of the artists for the loss of so much beauty.”[2]

Notice of Public Meeting, July 7, 1907. LHSA

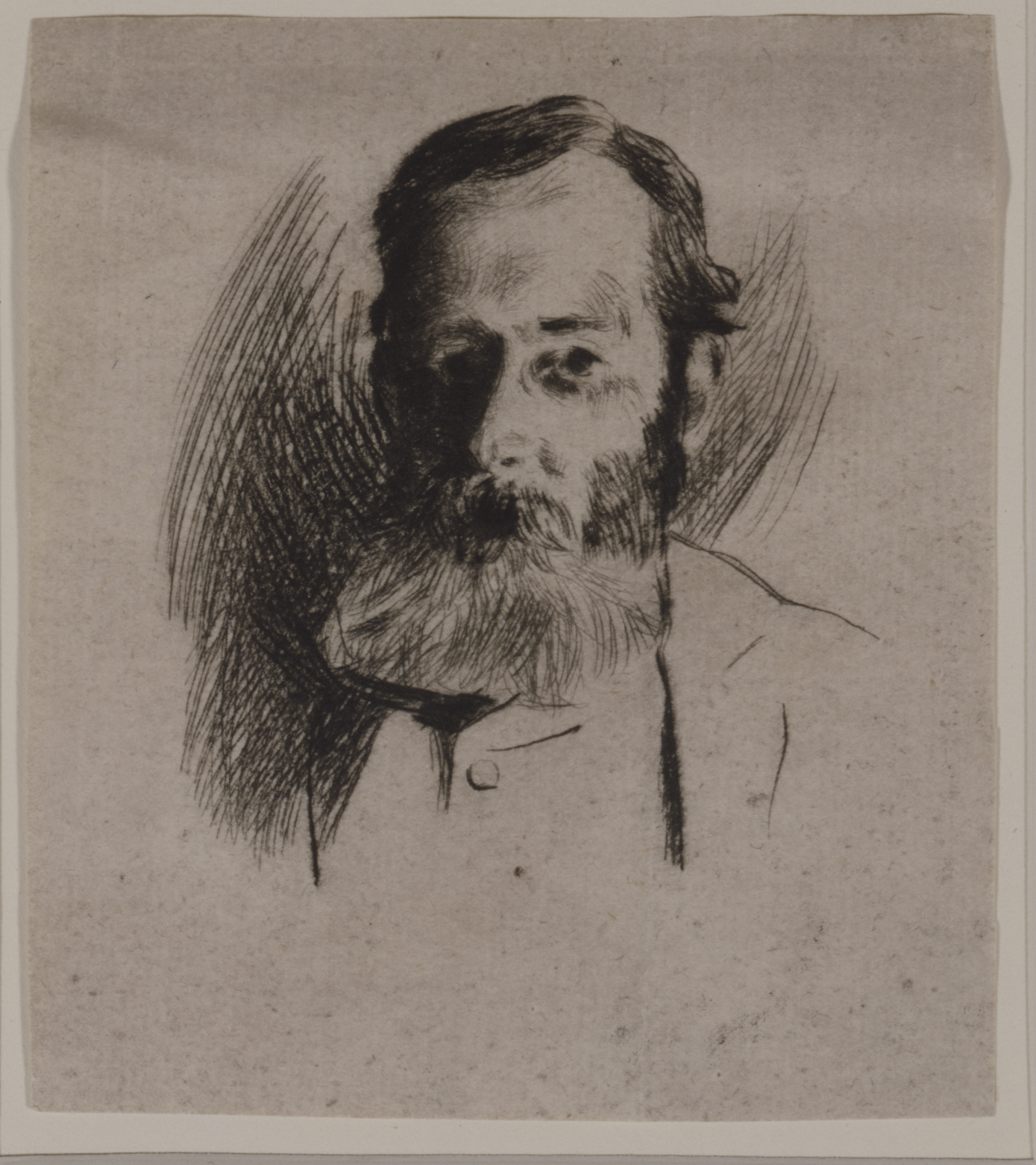

Within days conflicting views about the design of a new church became polarizing. Ernest Chadwick (1868–1916), a respected lawyer appointed to the building committee, launched the debate by advising: “unless sentiment insists upon a reproduction of the old work, a much better building (from the standpoint of pure art) may be erected out of stone.”[3] Rev. Edward M. Chapman (1863–1952) then proposed a brick replacement that would improve facilities, contain costs, and assure fireproofing. When New London architect Louis R. Hazeltine submitted drawings for consideration, he stated his preference for “Harvard brick” but recommended terra cotta “if a white exterior was essential.”[4]

Reverend Edward W. Chapman, April, 1908. Photocopy, LHSA.

Alarmed by these developments, influential residents supported by the town’s most prominent artists started a letter-writing campaign to assure that the church would be rebuilt as it had stood before the flames. Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury (1823–1917), an early and generous contributor to the building fund, sought Judge Noyes’ agreement: “No doubt your wish, as well as mine, is that the church shall be restored on the old foundations, and on the same plan. So many of us will give our contributions for this purpose that it will save much contention if it is accepted. It is not likely that there could be an agreement to accept any other style.”[5]

Katharine Ludington, ca. 1915. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection

By mid-July a majority of the building committee wanted “something new,” Katharine Ludington (1869–1953), who lived beside the church, wrote to Rev. William Adams Brown (1865–1943), a close family friend in New York. Explaining “the complicated nature of the calamity,” she asked for his help. Support had grown for “a fireproof brick building of ‘generally colonial character’, but ‘adapted to modern needs,’” she wrote, “—in other words, a nondescript institutional church, such as you might see in any second rate suburban town, instead of the distinguished, reserved, & perfect thing which we had before…. Now, could you not write a short notice of the church & the fire and assume in it that the admirers of the old church, in other places, expect the Lyme people to rise to this opportunity and re-produce the old—and get the Outlook to print it in one of their next issues? Or if you think a daily paper like the Sun or Times is better,—or perhaps both would be best of all!”[6]

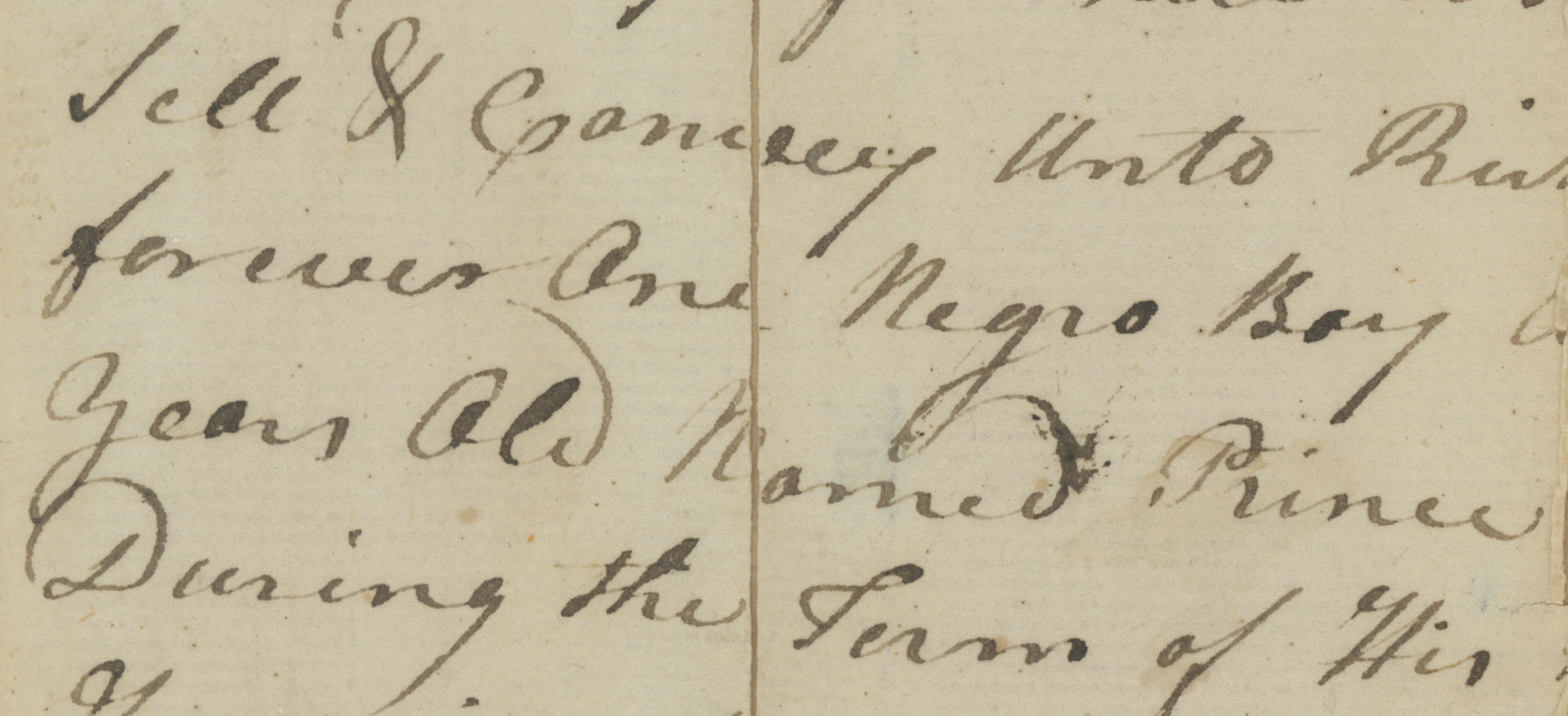

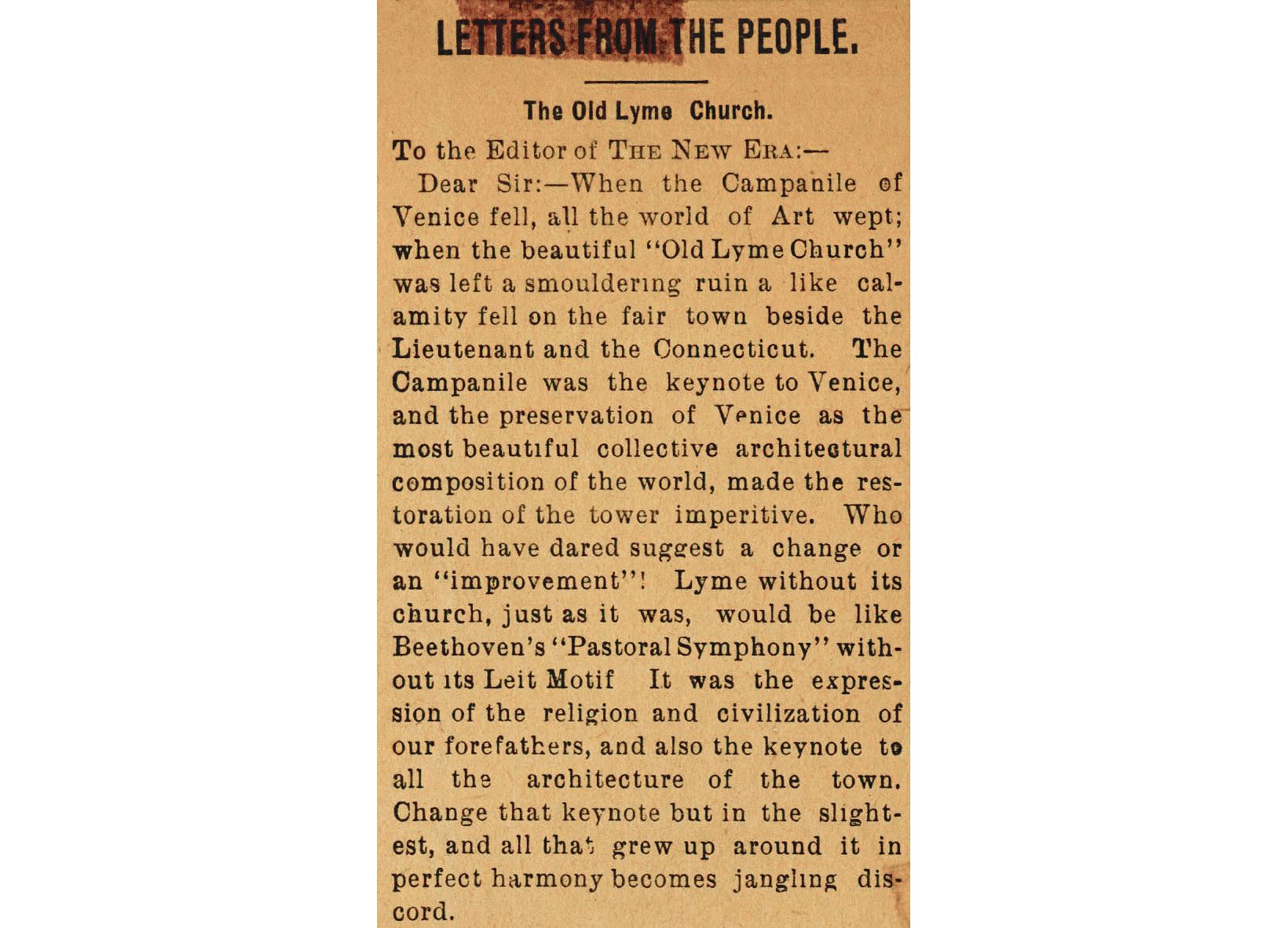

Charles Vezin letter, The Deep River New Era, July 26, 1907. LHSA

A letter to The New Era from artist Charles Vezin (1858–1942) on July 26 appeared in August in The New York Herald. Comparing the collapse of the Meetinghouse steeple to the fall of the Campanile in Venice, he urged replication of the original design. “There is talk,” Vezin wrote, “of building an ‘up-to-date structure’, or of ‘improving’ on the old one…. It will surely [be a] breach of good taste that would be a constant sorrow to all. Let the old church be reproduced without the slightest change!”[7] Donors also wrote forceful letters. “My card gives the terms of subscription on the understanding that the church will be substantially re-erected in the same general style as before,” Miss Ludington’s uncle wrote to Rev. Chapman. “This is so greatly my preference that I would not feel like giving as much were a different project decided upon.”

This was not the first time a threat to the white church had provoked heated controversy. In 1867 a sequence of satirical letters appeared in The New York Tribune supposedly offering the opinion of Louis Napoleon on whether the color of “the great Cathedral” in Old Lyme should be white or yellow. In a fictional reply the French emperor decreed: “Paint the church white.” The East Lyme Star, a weekly publication launched the previous year, was one of several newspapers to reprint the “interesting correspondence between the Church Committee and Louis Napoleon.” Its editors also offered a comment: “Many of our readers will remember that our sister town of Lyme has been shaken from ‘centre to circumference’ for some time past, and all because its excellent citizens could not agree upon what color their church should be painted.”[8]

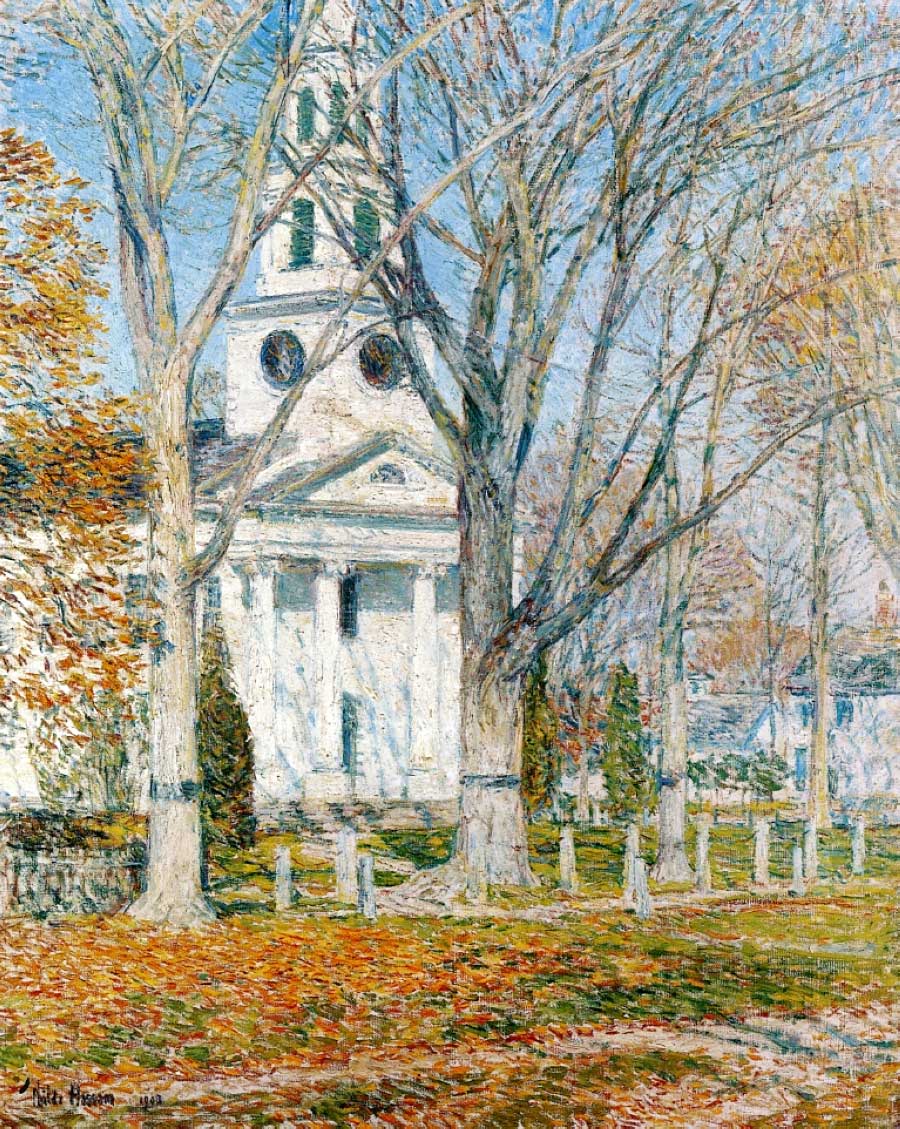

Childe Hassam, Church at Old Lyme, 1903. Private Collection

Phoebe Griffin Noyes (1797–1875), long a custodian of local culture, debunked the media stories in a family letter. “The trouble of the day is about the church & how it shall be repainted & there seems likely to be another civil war equal to the great war of the Liliputians,” she wrote to her son, but the media story was inflated and inaccurate. “No one has proposed painting [the church] yellow,” she said, but “some wise head put a piece in the Norwich paper & it has been copied in the Tribune, Hartford & Springfield papers saying that Old Lyme was convulsed with dispute about the color of the church some wanting it white & some yellow but that they had finally agreed to leave it to the ladies.” The ladies of the church, asked to pay for the redecoration, had considered painting the moldings white “& the body of the church one shade darker” to highlight the moldings, she wrote, but at a church meeting “it was voted to have it white…so white is to be the color.”[9]

Four decades later the white church again prevailed. The Building Committee had engaged in yet another “animated discussion of the material to be used in rebuilding the church” in mid-September, but a month later a vote brought resolution. A new structure would be erected “upon the lines of the old one.” Unanimity had still not been achieved, and both Charles and Ernest Chadwick voted “no,” but the town’s traditional streetscape would not be altered.[10]

Laying new cornerstone on old foundation, November 8, 1908. LHSA

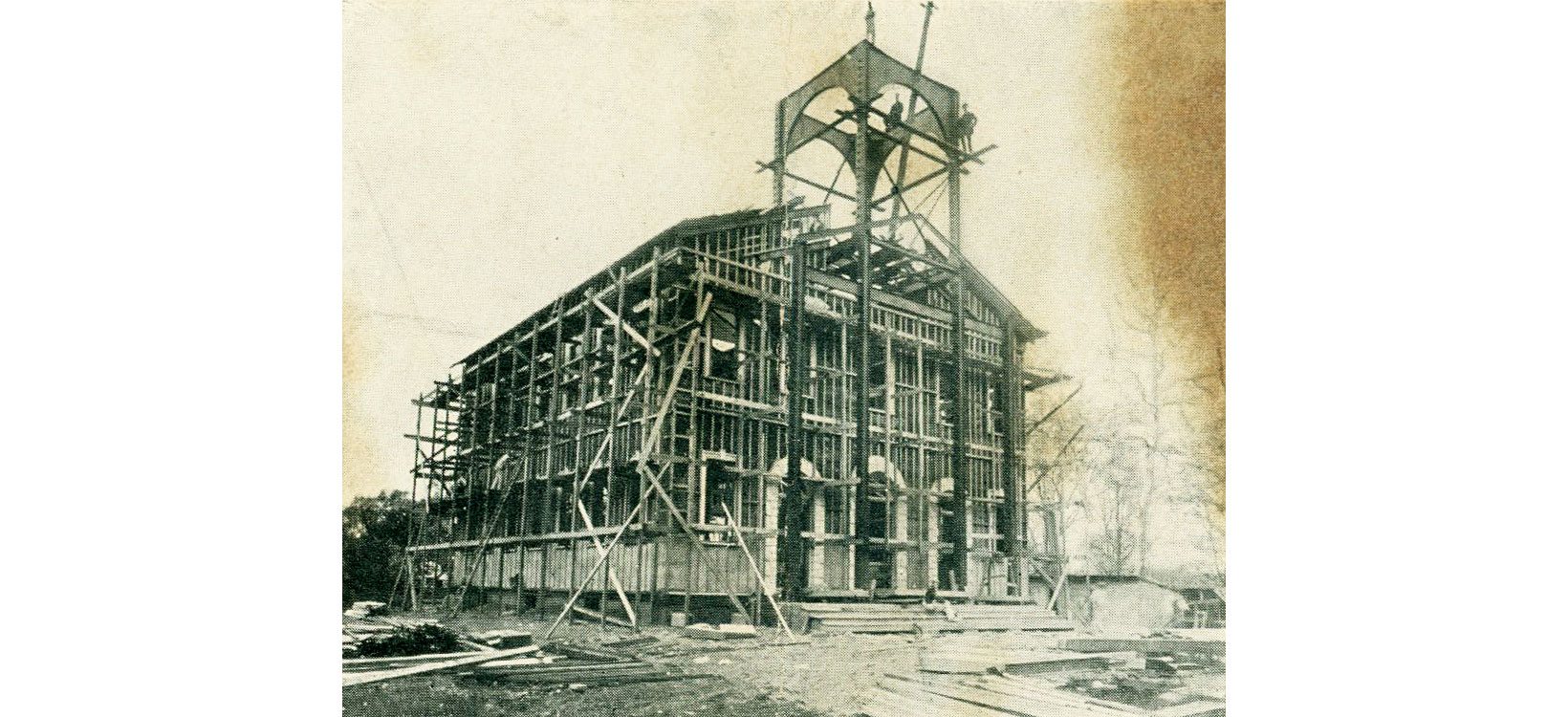

Meetinghouse near completion, showing scaffolding, 1910. LHSA

When it rose again on its former foundation, the Meetinghouse would adapt “old forms to new methods of construction,” architect Ernest Greene wrote. To provide fireproofing, he would use steel encased in cement for the frame and slate rather than wood shingles for the roof.[11] But the stately columns, the graceful spire, the familiar pews, and the exterior white clapboards would all be replicated as closely as possible. Miss Ludington rejoiced. “We haven’t enough beautiful things in this country to afford to play fast & loose with them,” she said.[12]

“A new replica of the ancient church in Old Lyme, CT,” July, 1910. LHSA

History Blog editor and Florence Griswold Museum trustee Carolyn Wakeman is also an archivist at the First Congregational Church of Old Lyme

[1] The Deep River New Era, July 12, 1907.

[2] Katharine Ludington to Arthur Ludington, July 10, 1907. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection.

[3] “Letters from the People,” The Deep River New Era, July 4, 1907. See also Mr. Chadwick’s previous article about the architectural history of the church: “The Evolution of Aestheticism: Idea of Structural Beauty as Embodied in Old Church at Lyme,” Connecticut Magazine, Vol. 8 (1902), pp. 201-204.

[4] Rev. Edward Chapman, Building Committee minutes, September 2, 1907. Courtesy First Congregational Church of Old Lyme (FCCOL).

[5] Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury to Walter C. Noyes, July 12, 1907. Courtesy FCCOL.

[6] Katharine Ludington to William Adams Brown, July 15, 1907. Courtesy New York Public Library.

[7] The Deep River New Era, July 26, 1907.

[8] Cited in “Paint the Church Yellow?” Old Lyme Gazette, July 18, 1974.

[9] Phoebe Griffin Noyes to Charles Phelps Noyes, October 6, 1867. LHSA.

[10] Rev. Edward Chapman, Building Committee minutes, September 13, 1907; Congregational Society of Old Lyme Records, Vol. 2, page 51. Courtesy FCCOL.

[11] Ernest Greene, “First Congregational Church, Old Lyme, Conn.,” ca. 1910. Courtesy FCCOL.

[12] Katharine Ludington to William Adams Brown, September 1, 1907. Courtesy New York Public Library.