by Carolyn Wakeman

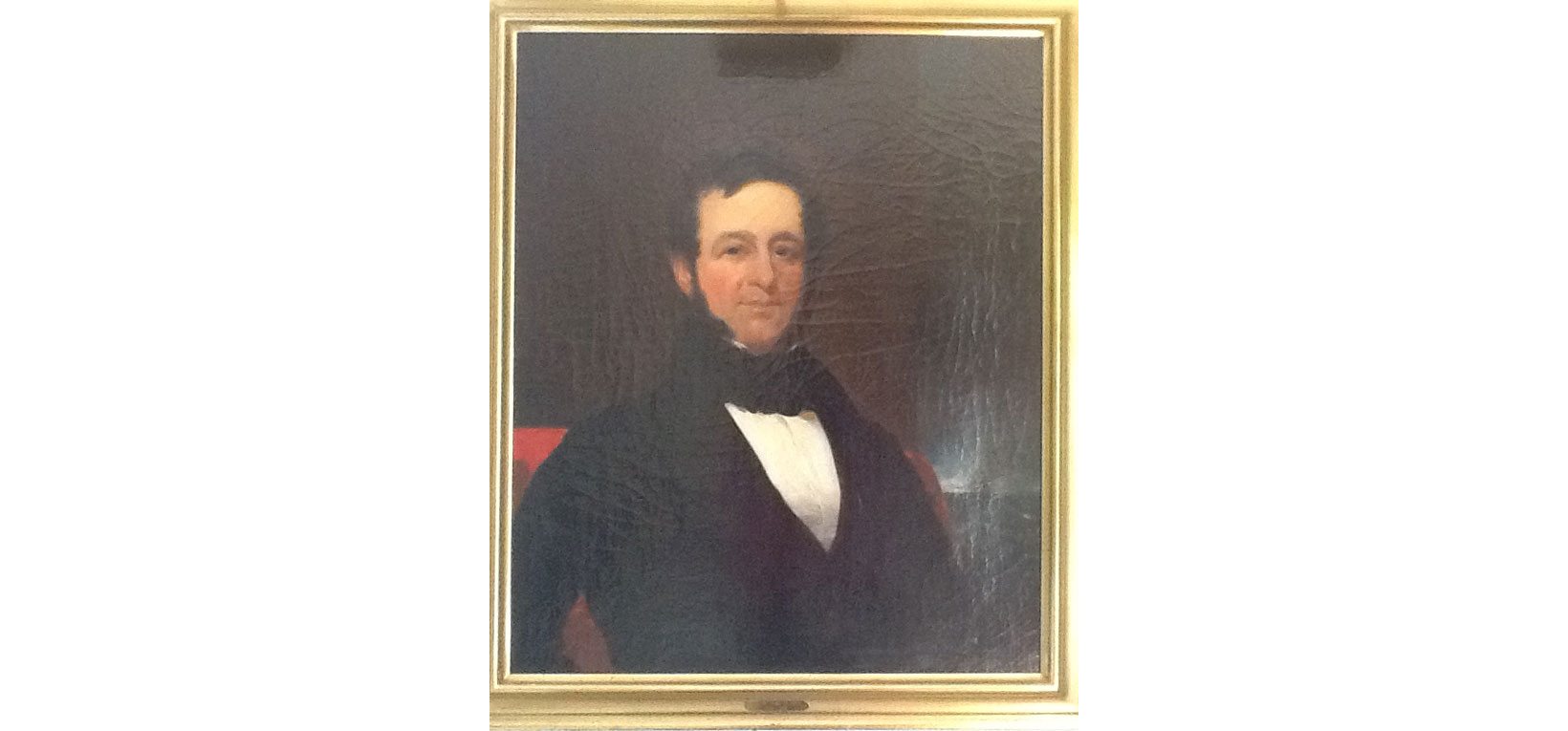

Feature Photo (above): Unidentified artist, Captain Daniel Chadwick. Private Collection

Daniel Chadwick (1795–1855), Lyme’s most celebrated sea captain, was known as the “admiral of the fleet.” When he relinquished command of the Sir Robert Peel in 1853, he had served with distinction as a trans-Atlantic packet ship commander for almost thirty years. Today his stately home with its rooftop captain’s walk recalls his illustrious maritime career. The shocking circumstances of his death are long forgotten.

The Fatal Deed

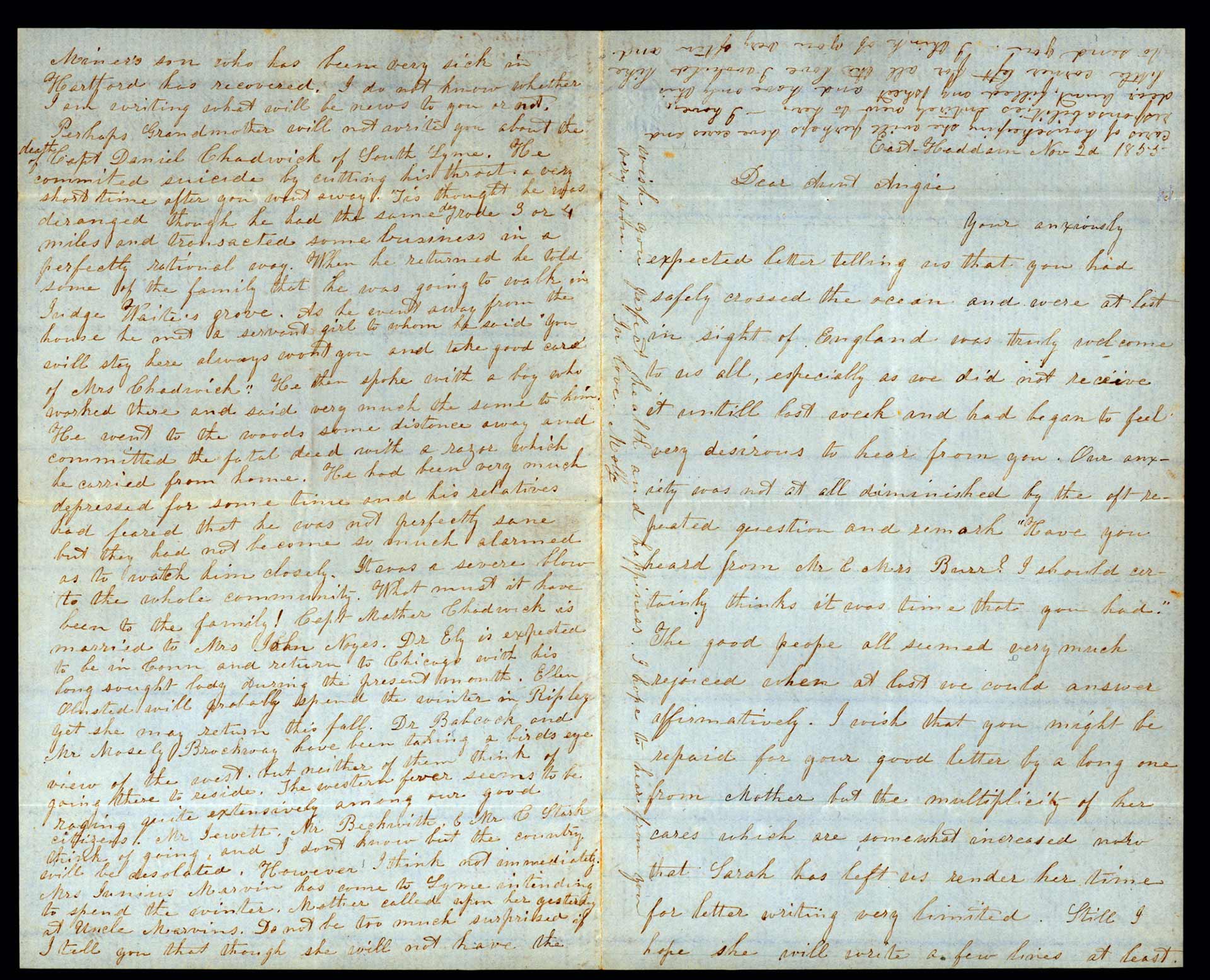

“Perhaps Grandmother will not write you about the death of Capt. Daniel Chadwick of South Lyme,” wrote Molly Griffin (1837–) to an aunt traveling in Europe. “He committed suicide by cutting his throat a short time after you went away.”[1]

Molly Griffin to Angeline Burr, November 2, 1855. LHSA

Molly Griffin to Angeline Burr, November 2, 1855. LHSA

Within days the Hartford Daily Courant had reported on the “melancholy suicide.” The “usually quiet village of Lyme was thrown into great excitement on Friday last, (Sept. 14th) upon the announcement that Capt. Daniel Chadwick was missing,” the obituary stated. “The news spread with rapidity, and in a short time a large number of the citizens of the village were out in search for him, and sad to relate, when found, life was extinct. He had succeeded in getting a razor from his house, with which he committed the fatal deed.”[2]

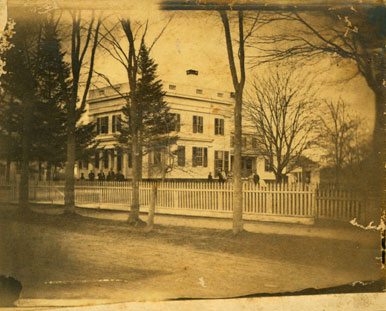

Daniel Chadwick house. Courtesy Werneth Noyes collection

Despite the community’s distress and the obituary’s details, Daniel Chadwick’s death received only occasional acknowledgment. Molly Griffin’s grandmother was not the only one who would not mention the local tragedy. Some of Lyme’s most devoted letter-writers remained silent about the sudden loss of a prominent resident. Judge Charles J. McCurdy, who lived nearby, received only a circumspect comment from a nephew in New York: “We were as you may well suppose much shocked at the death of Capt. Chadwick who was I believe very much esteemed by everyone.”[3]

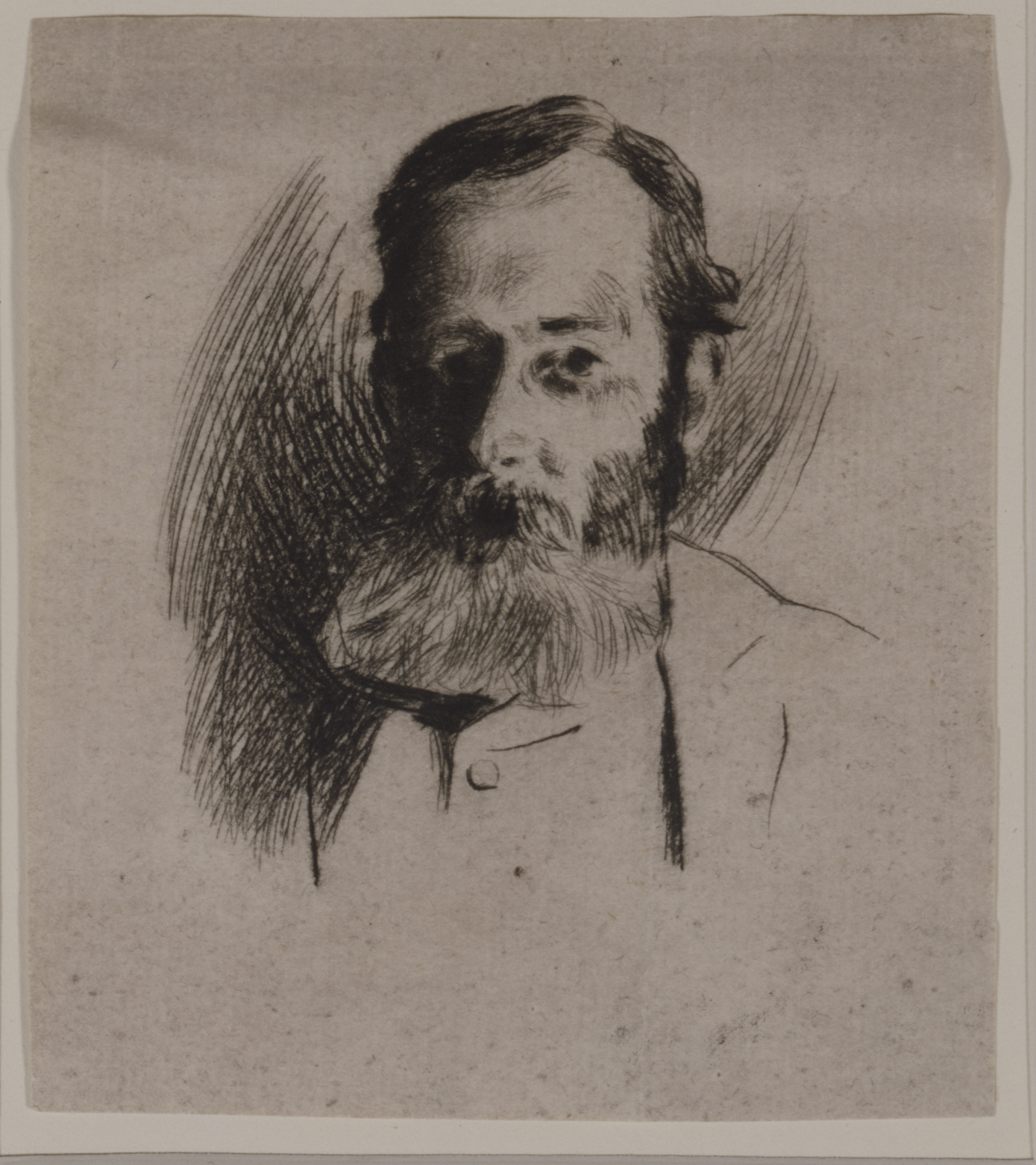

Judge Charles Johnson McCurdy, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1876. LHSA

Molly Griffin was a relative of Captain Chadwick’s by marriage and treated the death as a family matter. “’Tis thought he was deranged,” she wrote to her aunt, “though he had the same day rode 3 or 4 miles and transacted some business in a perfectly rational way. When he returned he told some of the family that he was going to walk in Judge Waite’s grove. As he went away from the house he met a servant girl to whom he said ‘you will stay here always wont you and take good care of Mrs. Chadwick.’

“He then spoke with a boy who worked there and said very much the same thing to him. He went to the woods some distance away and committed the fatal deed with a razor which he carried from home. He had been very much depressed for some time and his relatives had feared that he was not perfectly sane but they had not become so much alarmed as to watch him closely. It was a severe blow to the whole community. What must it have been to the family!”[4]

Chadwick monument, Duck River Cemetery, January 2013

Chadwick monument, Duck River Cemetery, January 2013

Daniel Chadwick’s suicide does not appear in the town’s vital records, whether because of incomplete listings or because of the unnatural cause of death. An inquest report has not been discovered, nor has a grave marker been found. A monument in Duck River Cemetery commemorates Daniel Chadwick with others in his family but cannot be precisely dated. The obelisk could have been placed in 1855 or erected later, when his wife Nancy Waite Chadwick died in 1859, when his son Capt. Walter Chadwick was lost at sea in 1864, or as a subsequent tribute from family members.[5]

Over time the distinguished ship’s master slipped from view. A descendant seeking information about his Lyme forebears in 2006 remarked: “I have information about other noteworthy members of the Chadwick family but cannot find anything on the elusive Captain Daniel Chadwick.”[6]

The Admiral of the Fleet

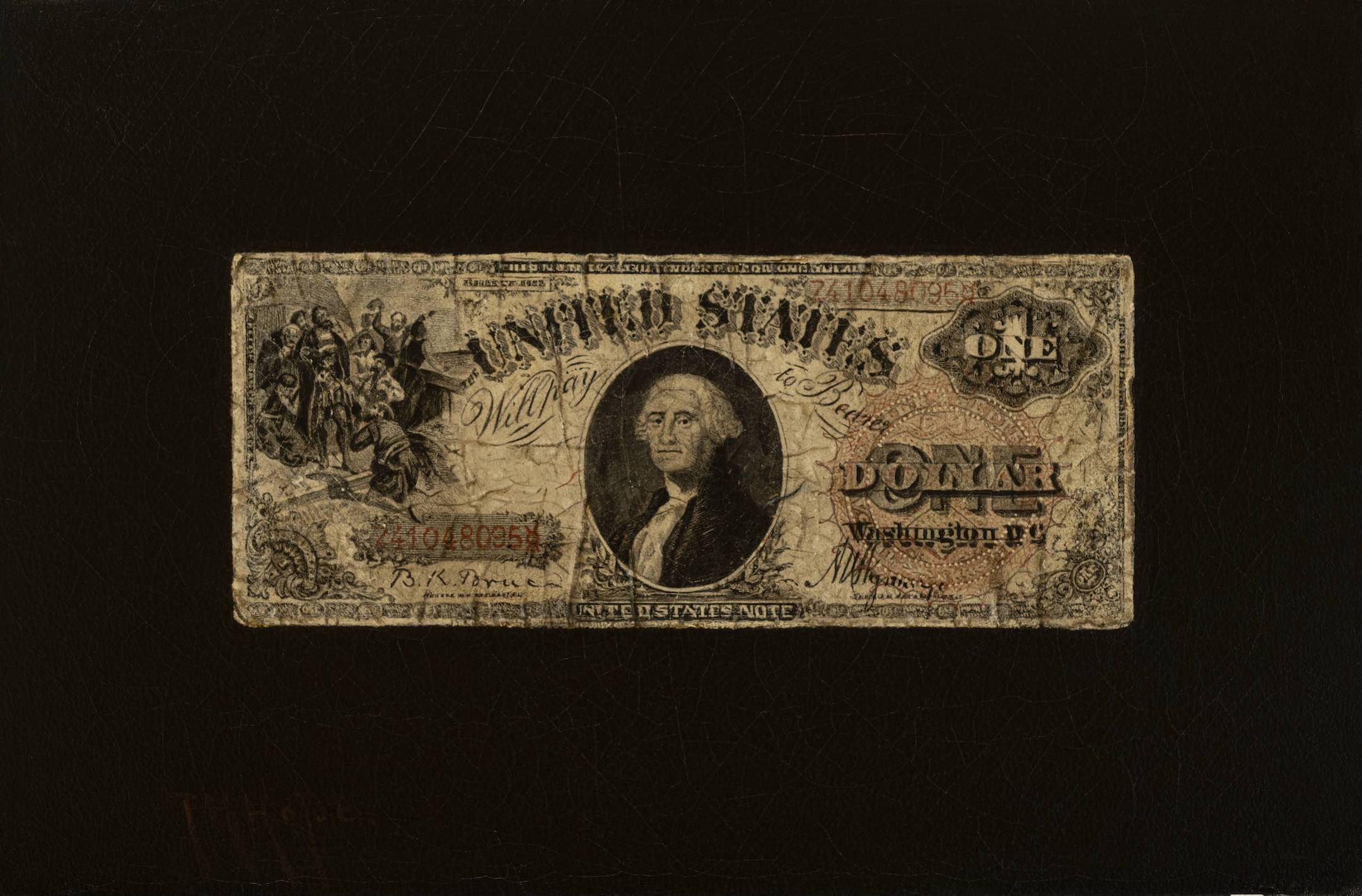

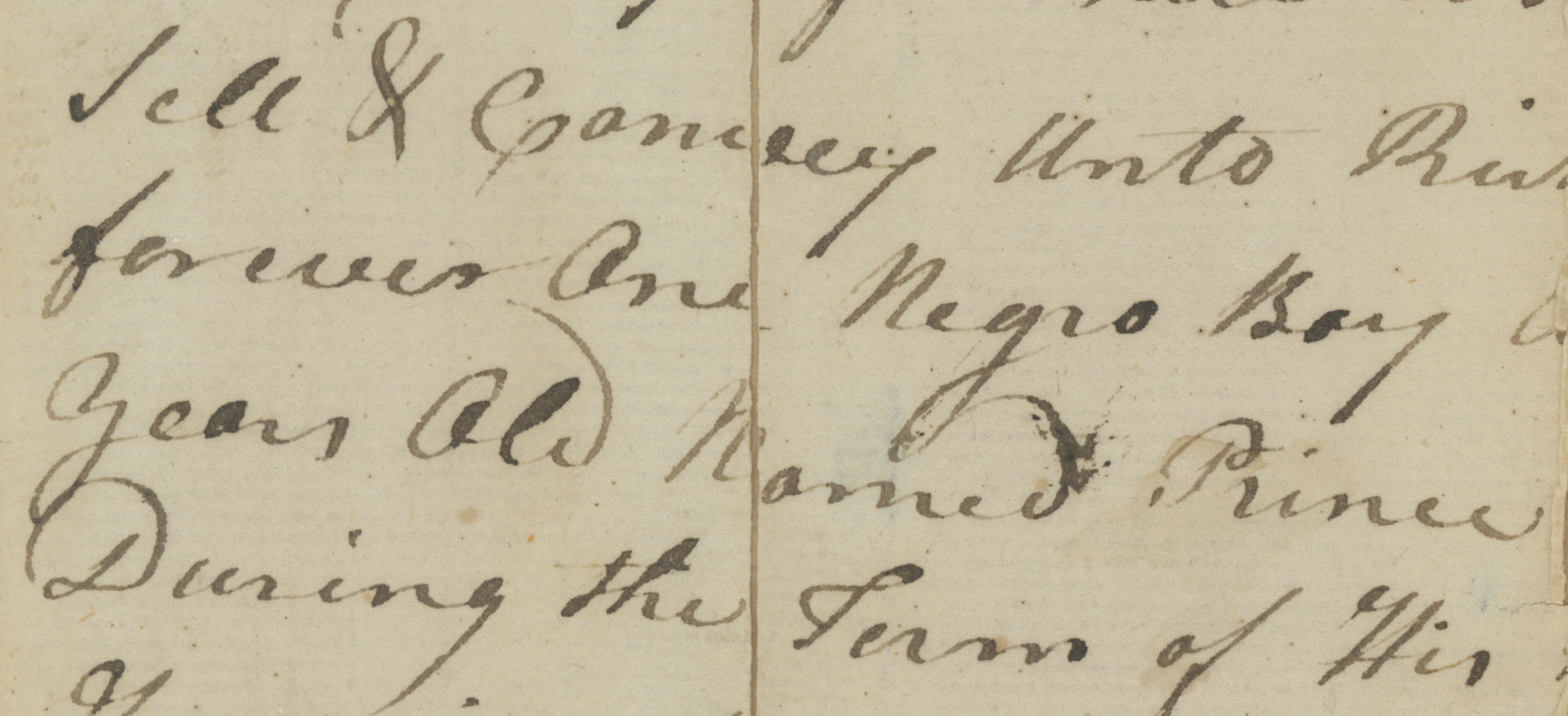

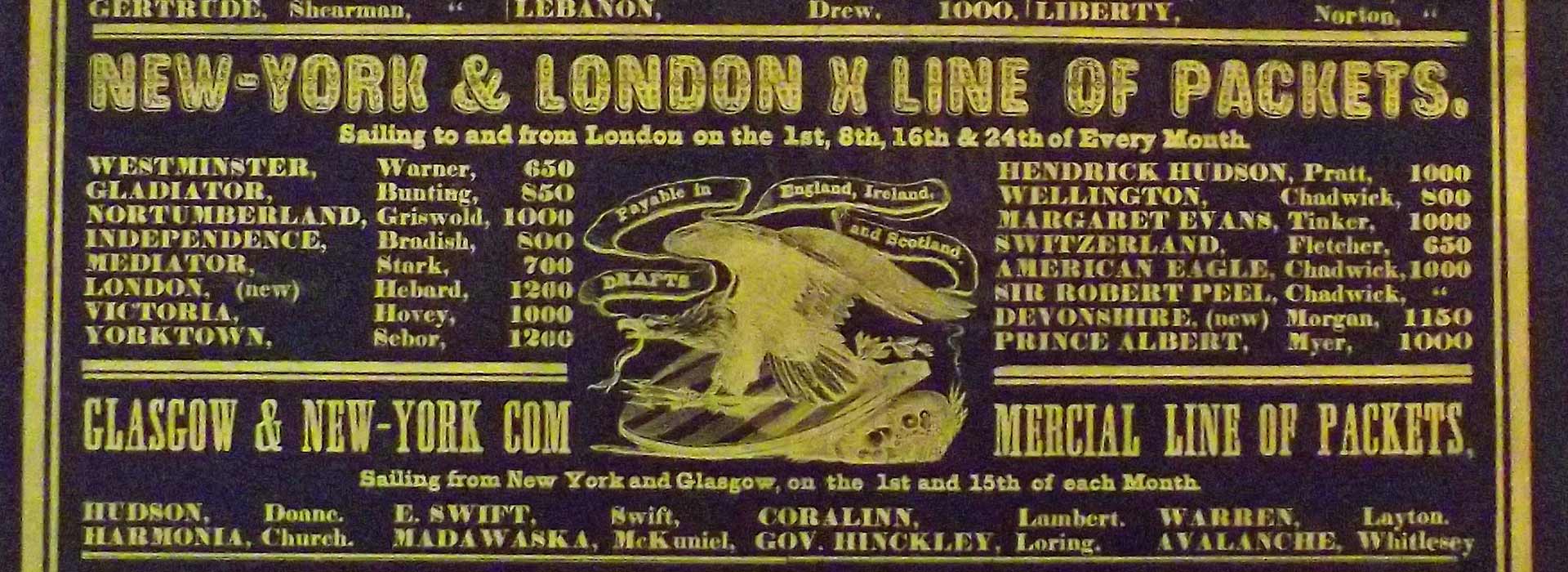

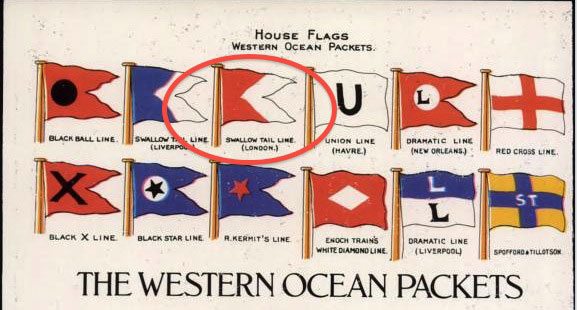

But if suicide obscured the life of Daniel Chadwick in Lyme, New York shipping announcements and broadsheets, along with letters and passengers’ memoirs, amply document his achievement. As captain of six handsomely outfitted vessels for the Grinnell, Minturn & Company’s Red Swallowtail Line—the Acasta, Corinthian, Samson,Cadmus, Wellington, and Sir Robert Peel—he secured longstanding admiration and trust.

Broadsheet, “Arrangements for 1849,” New-York & London Line of X Packets. Courtesy The Mariners’ Museum Collection

His earliest documented voyage, as first mate on the ship Cadmus in 1824, launched his reputation. After safe passage from Havre to New York, the Marquis de Lafayette, traveling at the invitation of President James Monroe, presented him with a set of silver compasses in a green, black, and white enamel cloissone case. The inscription read: “Gen. La Fayette, to Mr. Chadwick, 15th Aug 1824.”[7]

Red Swallowtail flag

A Lyme connection no doubt drew Lafayette’s attention to the ship’s first mate. In 1777 the French hero of the American Revolution had spent a night at the home of wealthy Lyme merchant and political activist John McCurdy (1724–1785). Forty years later, at the start of a triumphal tour of the United States, Lafayette returned to the McCurdy house a week after presenting his gift to Daniel Chadwick. “The General left Saybrook early Sunday morning, taking his breakfast at the house of Richard McCurdy, Esq., an eminent citizen of Lyme, and proceeded to New London,” a contemporary chronicler noted.[8]

General Lafayette, Photocopy. LHSA

Richard McCurdy house, 1890. LHSA

Richard McCurdy house, 1890. LHSA

From the time Captain Chadwick became master of the ship Acasta in 1825, many distinguished passengers would cross the Atlantic under his command. “In those days of rare foreign travel,” wrote Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury (1823–1917), the chronicler of Lyme’s elite families and a granddaughter of Richard McCurdy (1769–1857), “those who crossed the ocean were chiefly persons of education and high standing, from both continents. With these the captains associated and formed friendships.”[9] Packet ship commanders were widely regarded as the aristocracy of the seas.

Ship Acasta. Photograph. LHSA

Ship Acasta. Photograph. LHSA

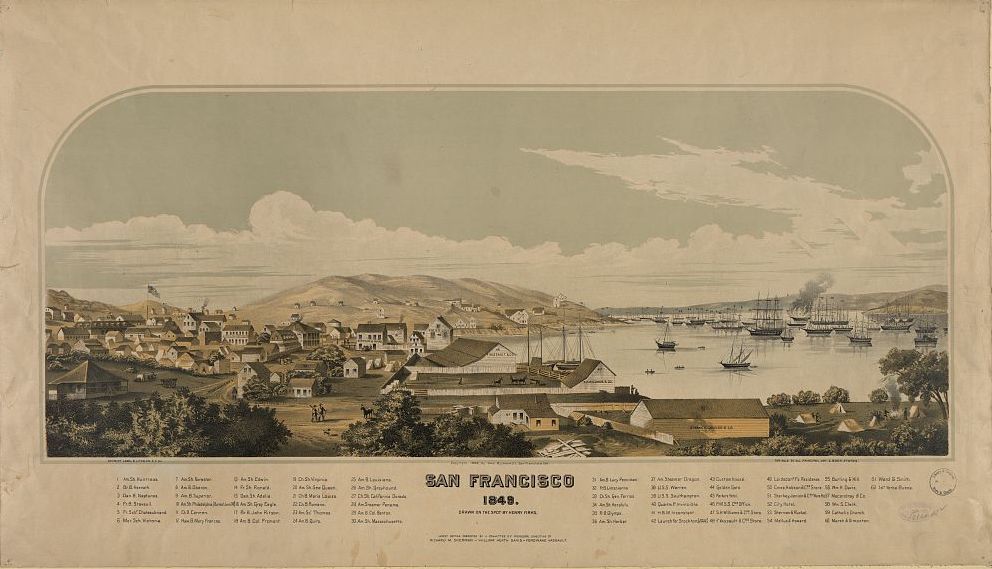

Cabin-class passengers like Evelyn McCurdy, who crossed on theOcean Queen under the command of her Lyme neighbor Captain Robert H. Griswold (1806–1882), enjoyed the comfort of private staterooms and the luxury of elegant meals served by stewards offering wines and liquors. Travelers below the main deck in steerage faced dismaying conditions. Taken on as return cargo on the New York-London packet ship crossings, thousands of immigrants paid a fraction of the $140 fare that Grinnell, Minturn & Company charged for “splendidly fitted” cabins. Packed together in unheated and unventilated quarters, the steerage passengers slept on straw mattresses, sometimes four or more to a berth. Bedding and provisions were not provided.[10]

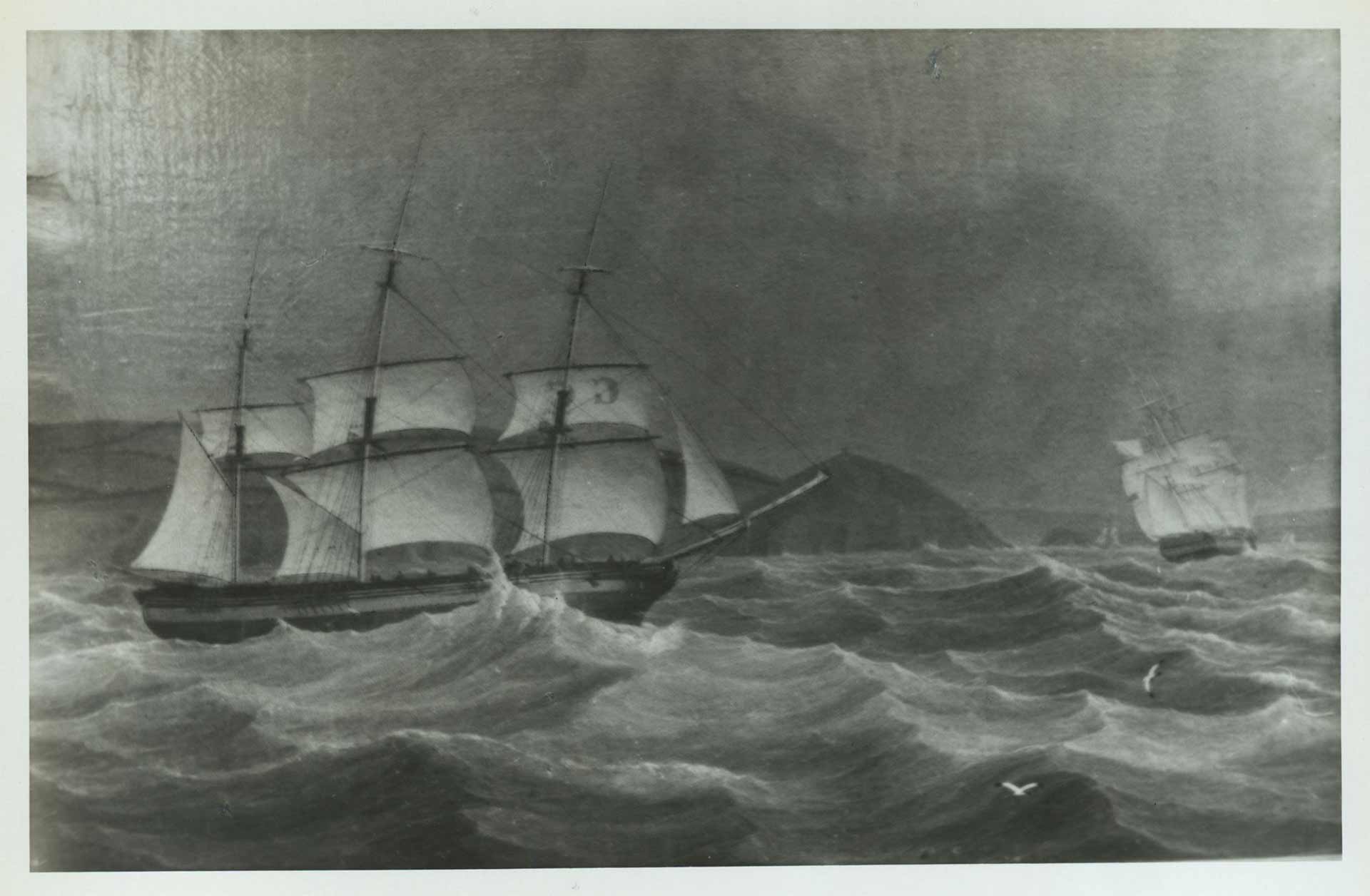

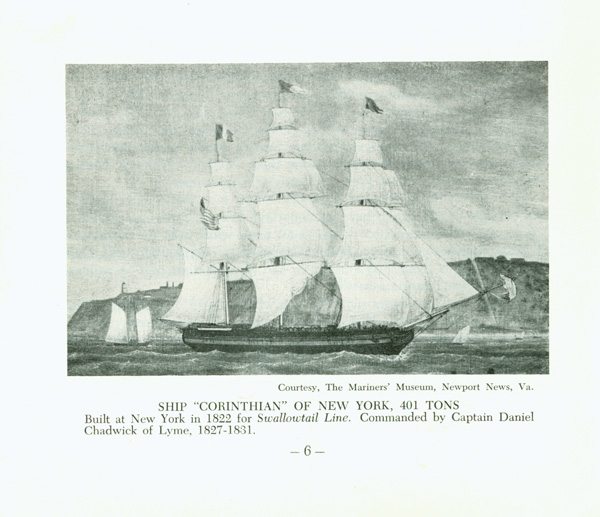

Ship Corinthian. Photograph. The Mariners’ Museum, Newport News, Virginia

An announcement of the scheduled crossing of the Corinthian on September 25, 1830, promoted the steerages as “lofty and comfortable.” But Thomas Augustus Trollope (1810–1892), brother of novelist Anthony Trollope, described the quarters below deck in less enticing terms. “We went on board the good ship Corinthian, Captain Chadwick, bound for New York, in the September of 1828,” Trollope wrote. “I confess that my first feeling on entering the place which was to be my habitation during the next few weeks was one of dismay…. the ventilation was very insufficient, and the whole place was, perhaps unavoidably, dirty to a revolting degree.” Trollope refused his assigned berth and instead slept on deck wrapped in his greatcoat. There he witnessed Captain Chadwick’s daring but masterful seamanship, most notably after sails ripped from the yardarms during a heavy gale.[11]

Depending on wind and weather, the packet ship crossings lasted from 20 to 54 days, and Captain Chadwick often made three round-trip voyages a year. Some journeys were “most agreeable,” but the ship Samson barely survived a sequence of disasters in December 1832.

A letter written from Portsmouth to his wife Nancy (1794–1859) recounted the harrowing events: “It has pleased kind Providence to protect the Samson and all its crew through a series of the most horrid accidents which could have occurred to any ship while at sea.”

First “a sea struck the ship taking with it the rudder and all the braces from the stern post, wrung off the rudder under the counter and in twenty minutes cleared off the stern altogether.” Then “the ship was struck with lightning during the most dreadful hail squall which came down on the fore topmast… [and] went down in the stanchions of the between decks into the lower hold where it set fire to a bag of cotton.” The fire spread quickly, burned “considerable cotton,” and almost ignited a barrel of turpentine stored beneath the bales. “You can easily realize my anxious moments during the shock,” he wrote, “and the relief after finding we had extinguished the fire. I thought before this accident I had all the anxiety possible for a man to have, or even to bear, as I had many lives depending.”[12]

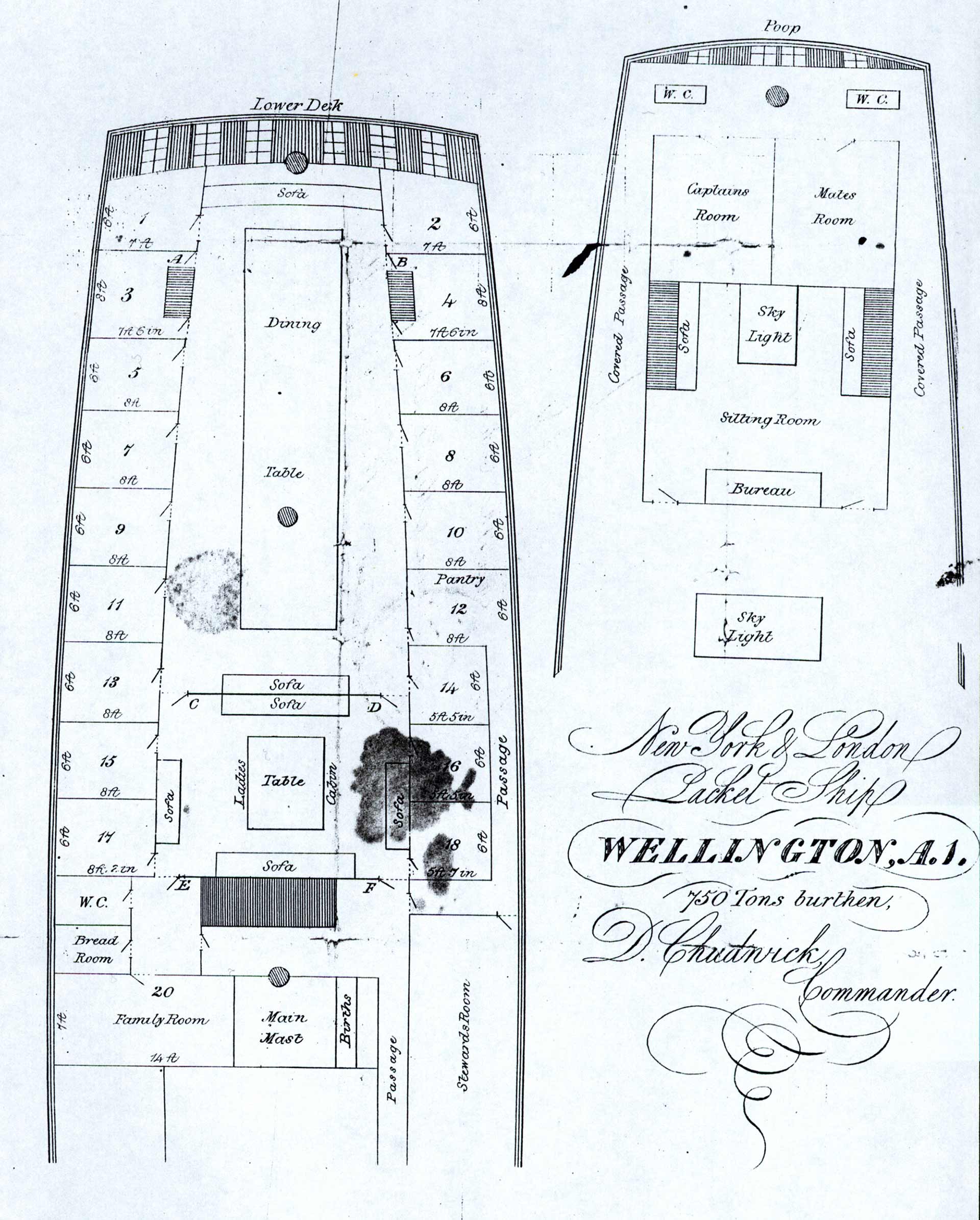

Plan of ship Wellington. Photocopy. LHSA

Plan of ship Wellington. Photocopy. LHSA

Despite the arduous challenges at sea, Captain Chadwick’s attachment to command never faltered. Five years later, as master of the newly launched and elegantly appointed ship Wellington, he reached the height of his celebrity. “My dearest Nancy,” he wrote from London. “I received a present of a pair of pistols by one of our passengers out, with this inscription, ‘Presented to Capt. Dan’l Chadwick by Prince Pirier Napoleon Bonaparte, July 4th, 1937.’ The pistols were once in the possession of the Greatest Soldier that ever lived, Napoleon Bonaparte.”

The Duke of Wellington’s (1769–1852) ceremonial visit to the ship that bore his name brought even greater honor. “The day was fine,” Nancy learned from her husband’s letter. “His Grace appeared delighted with the Ship and all he saw on board…he took lunch with us and drank the health of Capt. C. and success to the Ship under his command….He staid with us about one hour and left with the cheers of thousands who had surrounded the ship while he was on board. I rec’d this morning an invitation to dine with the duke on the 2nd.” The Times of London, which reported the Duke’s visit, noted even the “cold repast” that Captain Chadwick had served on board the Wellington.[13]

Francisco de Goya, The Duke of Wellington, 1812–14. The National Gallery, London

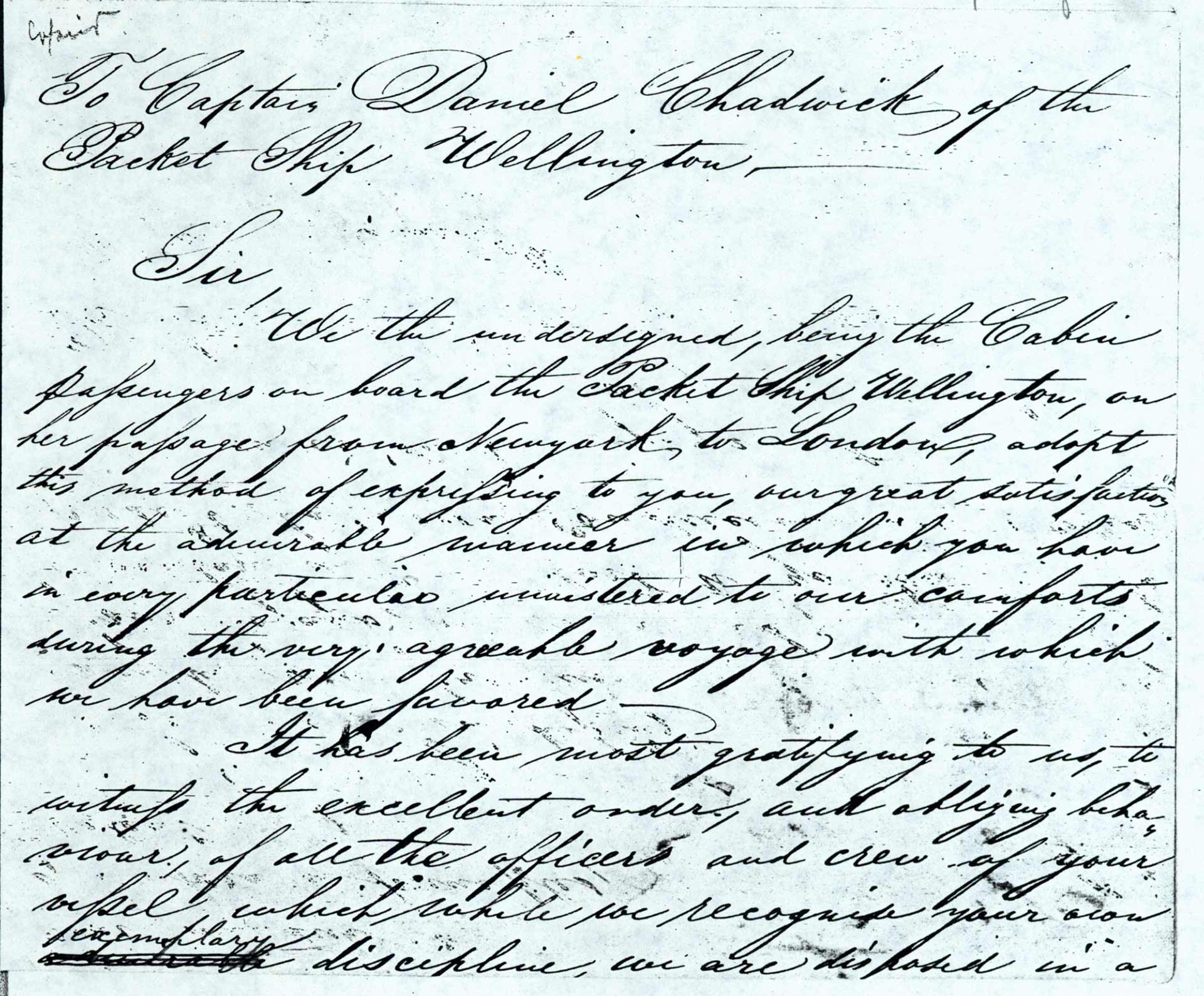

Grateful passengers continued to praise the esteemed captain’s experienced seamanship, gracious manners, and “exemplary discipline.” They also commended his “temperance principles.” A letter signed by 27 Cabin-class travelers on the Wellington in 1843 expressed “great satisfaction” at the admirable way in which he “in every particular” had ministered to their comforts. They attributed the “excellent order of all the officers and crew” to the sobriety of the seamen. When “extra-exertion” was needed, the captain allowed his crew to drink coffee but refused the daily pint of grog commonly dispensed to seamen.[14]

Letter from cabin passengers to Captain Daniel Chadwick, 1843, Photocopy. LHSA

Strict shipboard discipline bred resentment. Captain Chadwick’s younger brother Charles (1803–1884), who served repeatedly as theWellington’s first mate, chafed primarily at his secondary position. In letters to his wife Mary, he noted the ambition of “Brother Daniel” and also the arrogance of his authority. “He will have his flair ups,” Charles wrote, “but I keep cool and let vanity have its course, for the day will come when one head will be no higher than the other.”

But Mary Chadwick’s nephew John Hurlbut would sign up to serve under the demanding captain only if no other work was available. “I think I can stand to sail one voyage with your brother,” he wrote to Charles in 1849, after being offered the position of first mate on the Sir Robert Peel. But the next year his bitterness sharpened. “If there is nothing else open I shall sail with Capt. D.C. another voyage much against my will. I suppose I get along as well as anyone, but the Devil himself could not please him. I am not afraid of his flogging me. I suppose he will go to sea as long as he can stand, but he will not get me for mate much longer.”[15]

Harsh disciplinary measures imposed on the crew did not affect passengers’ views of the captain. As a twelve-year old boy H. H. Green traveled from London in steerage on the Sir Robert Peel. He reached New York with his family in late May 1851, wearied and “oh, how hungry” after the “ship biscuit, black sugar, rice and bad tea we had been subsisting on for so long.” Green recalled young whales sighted in the distance, a shark following the ship for days, and schools of porpoises “gambolling in the waves and flashing in the sunlight.” While he described the misery of the immigrant quarters, he also noted a universal respect for the captain.

South Street Wharves with packet ships, ca. 1855.

“At that time we crossed the captain’s name was Chadwick,” Green wrote. He was “every inch a gentleman, a fine capable officer who won the respect of all on board. . . .The steerage was crowded with passengers of all nationalities. . .If the black hole of Calcutta was much worse than that steerage, God pity the poor wretches who were shut up in it. Of course the officers did everything in their power to make the place endurable, but the moral and sanitary conditions were terrible. It could not be otherwise, nearly five hundred people crowded into so small a space, some of whom were shamelessly filthy….[but] it was no worse than other ships and quite likely it was much better than some of them.”[16]

Two years later Captain Chadwick relinquished command of the Sir Robert Peel to his son Walter, who had served most recently as his first mate. Three decades as a ship’s master had accustomed him to authority, celebrity, and life-threatening challenge. Not only did his position bring financial gain and access to a cultivated circle in London, but it allowed him, between sailings, to travel in England and on the continent. Most memorable was a trip to visit castles along the Rhine and in the Loire Valley accompanied by his good friend Captain Robert H. Griswold.[17]

Some local packet ship captains looked forward to a quiet life at home after the ardors of command. Captain Augustus H. Griswold (1789–1836) became a teacher at the Black Hall district school in his later years, and Captain Robert Griswold invested in a local start-up business, the South Lyme Nail Factory. But Daniel Chadwick remained restless on shore. “He says he should live out [only] half his days if he had got to stay at home,” Mary wrote in 1845.[18]

Thomas Coke Ruckle, Captain Robert Harper Griswold, 1840. Watercolor on paper. FGM, Gift of Dr. Matthew Griswold.

Thomas Coke Ruckle, Captain Robert Harper Griswold, 1840. Watercolor on paper. FGM, Gift of Dr. Matthew Griswold.

Retirement in Lyme

Daniel Chadwick’s birthplace, with wellsweep, South Lyme. LHSA

Daniel Chadwick was 58 when he retired. While commanding theWellington he had accumulated the financial resources to build a fashionable new home on Lyme Street on land adjoining the smaller house where he had lived with his family for fifteen years. “Your mother writes me that the lumber for the House has arrived,” he noted in 1840 to his son Daniel, Jr., then attending school in Middletown, “and I suppose by the time you and I get home [we] shall see it raised.”[19]

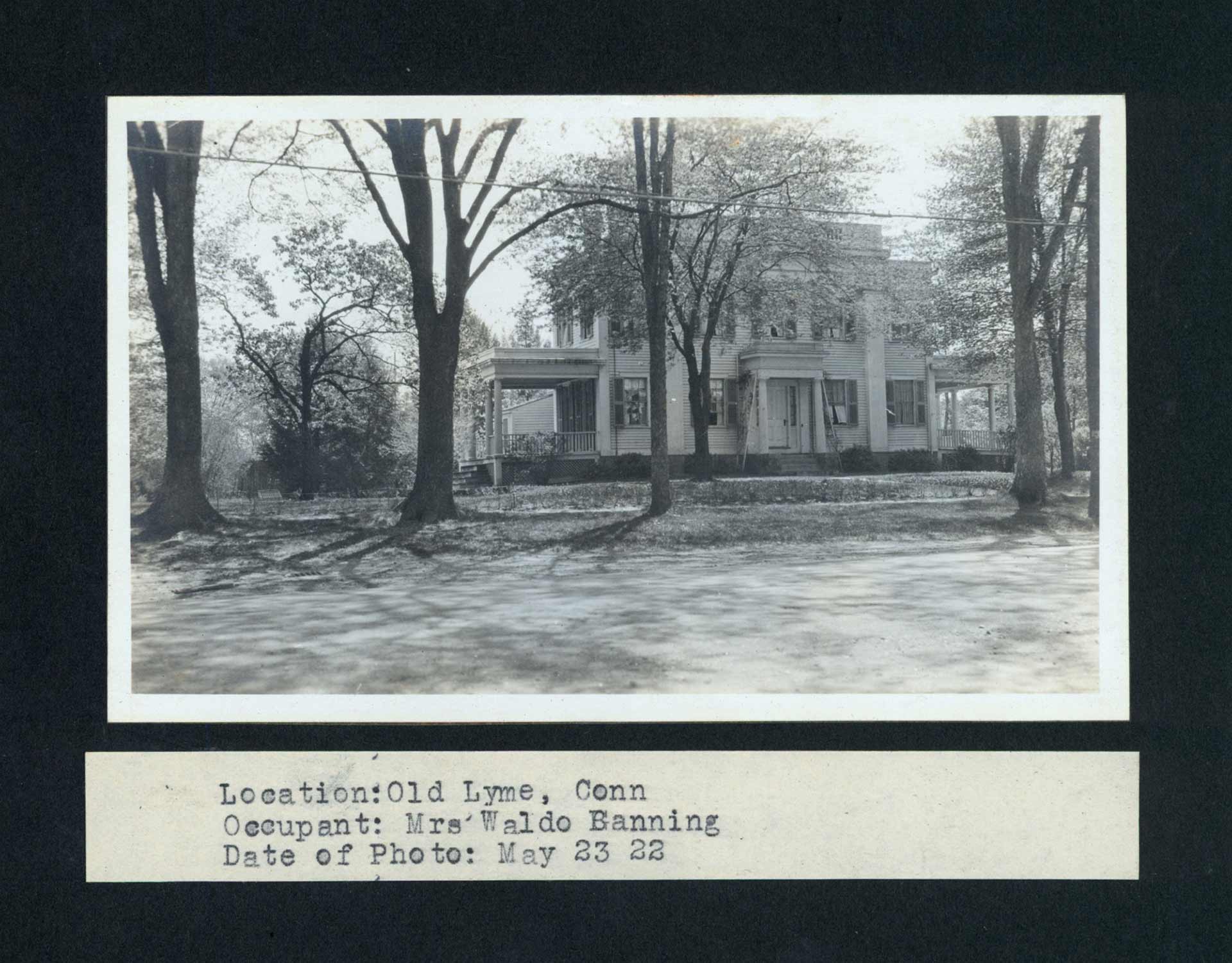

Daniel Chadwick house, 1922. LHSA

Daniel Chadwick house, 1922. LHSA

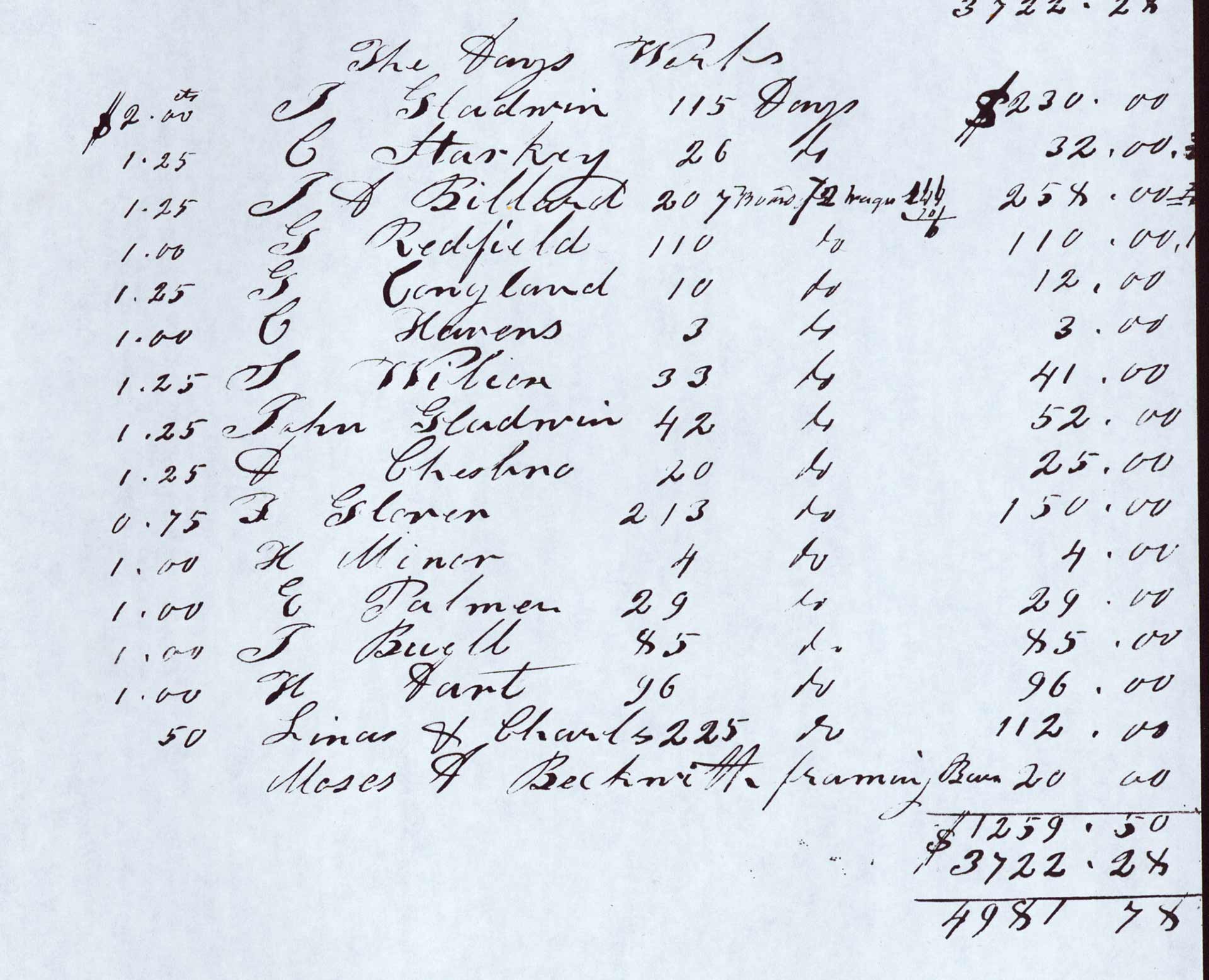

An itemized account of materials and labor shows that the Chadwicks’ mansion house, complete with barn, carriage house, and cow yard, cost $4,457, a handsome sum. By May 28th all but the final cash payment had been made to James Gladwin (1797–1880), the skilled carpenter and cabinetmaker from East Haddam who constructed the stately new dwelling.[20]

“Bills on Capt D Chadwick House,” Photocopy. LHSA

“Bills on Capt D Chadwick House,” Photocopy. LHSA

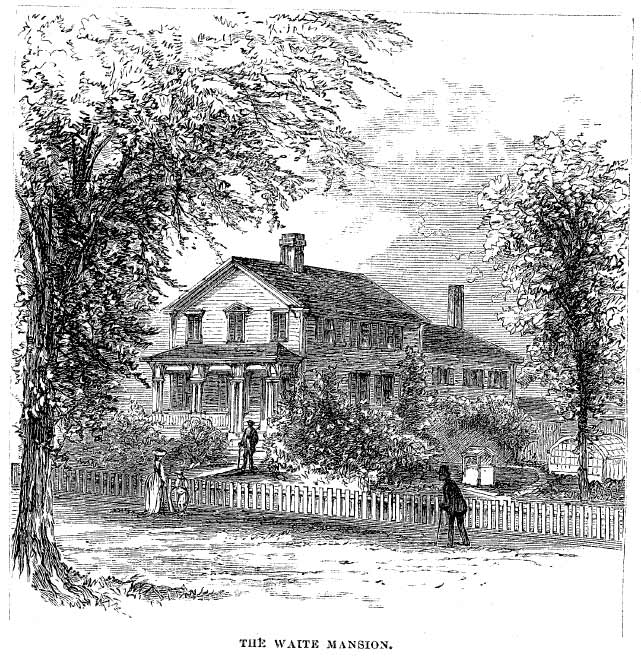

In retirement Captain Chadwick was surrounded by family and friends. To the south lived his wife’s brother, the distinguished jurist Henry Matson Waite (1787–1869), his friend since childhood. To the north lived his older daughter Anne Maria (1821–1890) in the house he had given her, “for love and affection,” when she married in 1842 the town’s distinguished young minister Rev. Davis S. Brainerd (1812–1875). The Brainerds’ home close by served as the parsonage and became “a sort of musical center, where people of the neighborhood would gather, bringing their instruments.”[21] The minister’s wife was 34 and had four young children when her father ended his life in Judge Waite’s woods nearby.

Attributed to Charles Parsons, The Waite Mansion. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine,February 1876. LHSA

Rev. Davis S. Brainerd house, 1936. LHSA

Captain Chadwick’s older son Daniel (1825–1884) had also married and prospered. After graduating from Yale, he studied law with his uncle next door, married Ellen Noyes (1824–1900), the daughter of a prominent local family, and established his own respected legal practice in town. Meanwhile Walter (1823–1864), the second son, had followed his father’s path and joined the “web-footed profession,” climbing rapidly from cabin boy to first mate under his father’s command. Only the Chadwicks’ youngest child Catharine (1842–1904) lived at home when her father died.

Frequent letters to Lyme during many years at sea had conveyed Captain Chadwick’s attentiveness and affection as a husband and father. While sending news of his crossings and information about his sailing schedule, he inquired closely after the family’s needs and interests, offering steady counsel and encouragement from afar. Most letters included details about the purchase of clothing or household goods, whether a stylish pink hat made in London for his daughter or a special oil lamp selected in New York for his wife. Concerned with his children’s education, he sent them to prominent New England schools: Anne to Miss Apthorpe’s in New Haven, Daniel to Isaac Webb’s in Middletown where his classmate was the future President Rutherford B. Hayes, and Walter to Williston Academy in Springfield.

Mercy Mather Chadwick Waite, with ship’s painting. LHSA

Mercy Mather Chadwick Waite, with ship’s painting. LHSA

Like other Lyme sea captains’ wives, Nancy Chadwick would wait for weeks at a time to receive news of a ship’s safe arrival. Her close relatives shared that uncertainty. Daniel’s three younger brothers were all ship’s masters, as were her own brothers Nathaniel and Samuel Waite, who had married her husband’s sisters Mehitable and Mercy Chadwick. During long intervals with their husbands far from home, the Waite and Chadwick women raised their young children while also managing the economic affairs of their households and farms.

Despite the hazards at sea and the love of his family, Captain Chadwick grew restless during long intervals between voyages. “Capt. D Chadwick says he is sick of staying at home,” his sister-in-law Mary noted in 1845. (137)[22] A decade later his family did not recognize the extremity of his distress.[23] Just hours before his death he rode off “in a perfectly rational way” to settle some final matter of business. Then he disappeared into Judge Waite’s woods.

Novelist James Fenimore Cooper (1789–1851), after crossing from London to New York in 1832 on the ship Samson, modeled a fictional Connecticut sea captain in Homeward Bound (1838) partly on Daniel Chadwick. The seasoned mariner in that adventure tale looked forward to a peaceful retirement: “on the banks of the Connecticut whence all the packet men are derived and whither they repair when their careers are run, as regularly as the fruit decays where it falleth, or the grass that has not been harvested or cropped withers on its native stalk.”[24] Daniel Chadwick’s life had a more troubled ending.

[1] Mary E. [Molly] Griffin to Angeline Lord Burr, November 2, 1855. Burr Papers, Box 2. LHSA.

[2] Hartford Daily Courant, September 17, 1855. An obituary article also appeared in The Daily Palladium (New Haven) on the same date.

[3] Theodore F. McCurdy to Charles J. McCurdy, n.d., courtesy Old Lyme Historical Society.

[4] Molly Griffin’s mother Mary Lord Griffin (1816–1858) had notified her sister Angie in England of the suicide three days after the event: “Capt. Daniel Chadwick committed Suicide last week. How melancholy! It produced great excitement in Lyme.” Mary Lord Griffin to Angeline Lord Burr, September 17, 1855, Burr Papers, Box 2. LHSA.

[5] See “Record of Deaths in the Town of Lyme,” 1855.

[6] Daniel Woodhead III, query posted by H-History.

[7] Chadwick Papers, LHSA.

[8] “Obituary Sketch of Charles J. McCurdy,” Connecticut State Library.

Judge Elias Perkins, American Historical Register (August 1895).

[9] Edward Salisbury and Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury, “Introductory Notes on Lyme,” Family Histories and Genealogies (New Haven, 1892).

[10] Evelyn McCurdy to Charles J. McCurdy, March 25, 1851, courtesy Old Lyme Historical Society; Daniel Chadwick Papers, Box 7, LHSA. See also Michael Carolan, “An Irish Passenger, An American Family, and Their Time, 1847-2010.” According to Carolan, Robert Minturn, an owner of the Red Swallowtale Line, remarked that the $5 million spent by emigrants on ship fares in 1847 substantially reduced the cost of carrying freight, and thus lowered the cost of American cotton and grain to English buyers.

[11] “New York Line of Packets,” Immigrant Ships Transcribers’ Guild, Maritime Newspaper Articles, 1830. Thomas Augustus Trollope, What I Remember (New York, 1887), pp. 110-114.

[12] Daniel Chadwick to Nancy Chadwick, January 4, 1832. Chadwick Papers, LHSA.

[13] Daniel Chadwick to Nancy Chadwick, July 31, 1837, Chadwick Papers, LHSA; “Visit of the Duke of Wellington to the St. Katharine Docks,” The Times, July 29, 1837.

[14] Letter to Captain Daniel Chadwick of the Packet Ship Wellington, June 29th, 1843, Daniel Chadwick Papers, Box 7, LHSA. Captain Chadwick’s testimony to British medical examiners about the effectiveness of of shipboard temperance principles appears in “On the Use and Abuse of Alcoholic Liquors,” British and Foreign Medico-Chirurgical Review (April 1851).

[15] John Hurlbut’s mother Caroline Rowland was Mary Chadwick’s sister. See Caroline Fraser Zinsser, Dear and Affectionate Wife: The Letters of Charles and Mary Chadwick of Lyme, Connecticut, 1828-1851 (East Lyme, 2005), pp. 115, 117, 126-127. After Hurlbut took command of the Patrick Henry for the Blue Swallowtail Line during the peak years of the Irish famine, he reportedly approved the transport of illegal loads of immigrant passengers in desperately crowded quarters in steerage. See Carolan, “An Irish Passenger.” The “spectacle of wretchedness” of steerage passengers who arrived in New York in March 1851 on the Sir Robert Peel prompted an editorial in The New York Herald denouncing the shipping of emigrants to America “in this wholesale way.” Cited in Tyler Anbinder, Five Points: The 19th-Century New York City Neighborhood (New York, 2001), p. 65. Captain Charles Chadwick served as acting commander of the Sir Robert Peel on that passage. On February 9, 1851, before sailing to New York, he wrote to Daniel Chadwick in Lyme that he had “a large family to bring to America—290 steerage,” 20 cabin passengers, and “a full freight.” Zinsser, p. 130.

[16] H. H. Green, The Simple Life of a Commoner: An Autobiography (Decorah, Iowa, 1911), pp. 20-22.

[17] Chadwick Papers, LHSA.

[18] Edward L. Griswold, “Tales of Black Hall, Its Teachers and Mariners,” The Day, April 6, 1916; cited in Zinsser, p. 96.

[19] Captain Daniel Chadwick to Daniel Chadwick, Jr., July 24, 1840. Daniel Chadwick Papers, Box 7, LHSA.

[20] “Bills on Capt D Chadwick House.” Chadwick Papers, LHSA.

[21] Lyme Land Records, 37:403; Landmarks of Old Lyme, Connecticut (Old Lyme, 1935), p. 10.

[22] Zinsser, p. 96.

[23] At the Hartford Retreat, established in 1824 to treat the mentally ill, attendants carefully watched patients with depression “to forestall suicide and to divert attention to hopeful subjects.” Lawrence B. Goodhart, Mad Yankees: The Hartford Retreat for the Insane and Nineteenth-Century Psychiatry (Amherst, 2003), p. 66.

[24] Cited in Chadwick Papers, LHSA.