Preview our upcoming exhibition Fresh Fields with this new perspective on Charles DeWolf Brownell’s view of Joshua’s Seat, a rock formation on the Connecticut River with ties to Native American history that also reveals the role the artist’s family played in the slave trade.

By Carolyn Wakeman

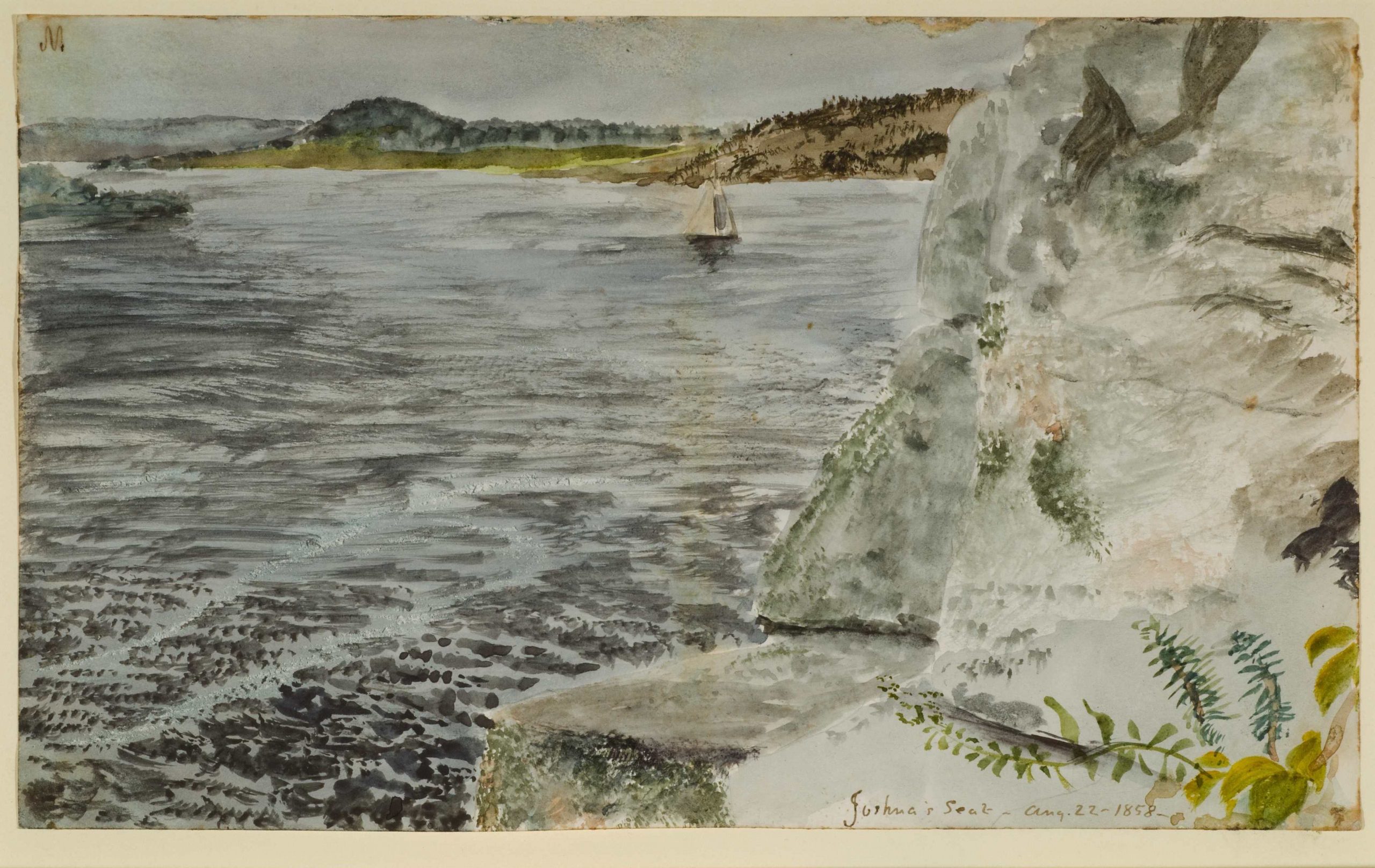

Featured Image: Charles DeWolf Brownell, Joshua’s Seat, 1858. Watercolor on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, Purchase, 2006.15

Charles DeWolf Brownell (1822–1909), whose watercolor painting Joshua’s Seat will be featured in the Florence Griswold Museum’s summer 2020 exhibition Fresh Fields, grew up in Hartford but had close family ties to Lyme. Trained in the landscape style of the Hudson River School and influenced by the paintings of his friend Frederic E. Church (1826–1900), Brownell repeatedly sketched and painted in the scenic town where his mother’s family were early and influential settlers. In Joshua’s Seat he captures the flat cleft in a steep granite ledge along the Connecticut River that Zebulon Reed Brockway (1827–1920), who grew up nearby, described as a “kingly seat” with “a legend.”

Landscape and Legend

Brockway’s autobiography Fifty Years of Prison Service notes that the cliffs were “always in the sight and mind of the children living near” and describes “King Joshua” as an aboriginal Indian chief who “was wont to seat himself and survey and rule his tribe” from the cleft in the rocks. A Selden family genealogy includes a more threatening version of the legend, claiming that the “royal Indian,” from his seat at the top of the perpendicular cliff, would “fire his arrows upon the white men as they sailed up the Connecticut River.” A genealogy of the Harvey family describes the Joshuatown section of Lyme as “at one time the favorite haunt of Attawanhood (1630–1676), or Joshua,” and states that he discharged arrows from his cliff-top seat “at persons passing up and down the river in boats or canoes and compelled them to land and pay him tribute.” Today sightseers on a river cruise to observe bald eagles are told that a Mohegan sachem would look down and watch his tribe members fishing below.[1]

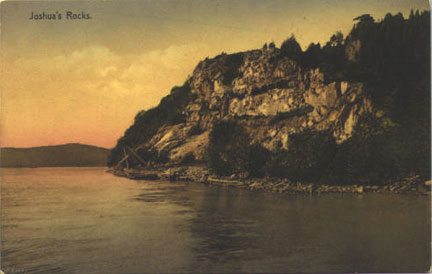

Joshua’s Rocks in winter, Hartford Courant (February 22, 2019)

Joshua’s Rocks inspired both awe at their “grandeur” and practical plans for their use. A visitor to Lyme in 1877 writes that he could offer only a “faint idea” of the memorable sight. He describes “rocks by the acre” piled up and resting on one another, “as secure as the Rock of Ages.”[2] Others that year viewed the 60-foot high granite bluff as a commercial opportunity. A photograph by George Bradford Brainerd (1845–1887) shows two schooners tied up at the cliffs, waiting to load blocks of stone hewn from its working west face. The magazine Stone reported in 1894: “The old Joshua Rock Quarry at Essex, Conn. (sic), that has been lying idle for the past year will soon start up with a gang of quarrymen of two hundred or more.” The quarry would be “run by New York capitalists to get out paving stones for New York City.” In 1911 the Joshua Rock Granite Quarry, recently operated by C. E. Pratt of Essex, lay idle again.[3]

George Bradford Brainerd, Joshua Rocks, Connecticut River, August 1877. Collodian silver glass wet plate negative. Brooklyn Museum/ Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection

Joshua’s Rocks, postcard, showing remnants of a crane and dock used by boats picking up stone from the quarry

In a recent memoir that chronicles life at Brockway’s Ferry, Elizabeth Putnam (1912–2007) recalls her father taking her by the hand when she was a little girl and leading her across the steep face of the rock to sit in Joshua’s seat. She presents the “looming bluff” not as a place of legend but as a marker of local history. The Connecticut General Assembly directed that Attawanhood, who used the English name Joshua, be granted land for his lifetime in the area of Lyme later called Joshuatown, she writes. She also observes that his stone seat offered a “wonderful” view of the river.[4]

Charles de Wolf Brownell, View of the Connecticut below Brockways. Graphite on paper. Courtesy Cooley Gallery, Old Lyme, Connecticut

Landscape and History

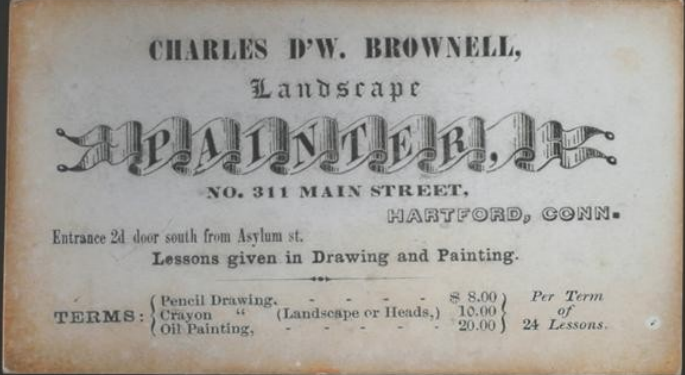

Charles DeWolf Brownell’s close-up depiction of Joshua’s legendary seat, dated August 22, 1858, captures the sweeping vista from the rock ledge while evoking the landscape’s layered history. Brownell was born in Providence but moved with his family to Hartford early in his childhood. Turning away from the practice of law and influenced by the artistic talent of his mother Lucia Emilia DeWolf Brownell (1796–1884), he published in 1853 an illustrated history of America’s native tribes. The next year, while studying landscape painting, he received an M.A. degree from Trinity College, and in 1855 he began offering lessons in painting and drawing.[5]

Trade card of Charles DeWolf Brownell, offering lessons in drawing and painting, ca. 1855. Connecticut State Library (Acc. #2016.193)

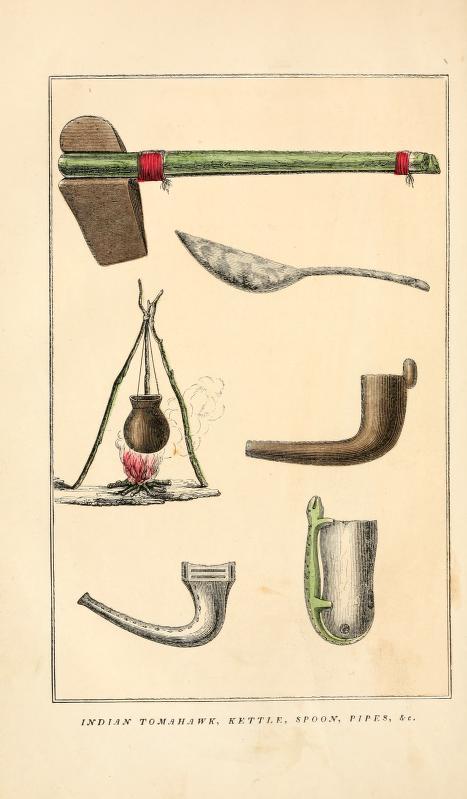

Brownell’s perspective on the past in The Indian Races of North and South America challenged prevailing impressions of local Indians as devious, hostile, and menacing. When looking back at the massacre of Pequots by colonial troops in Mystic in 1637, he states, one must acknowledge “the circumstances of terror and anxiety which surrounded the early settlers,” but one must also confess “that here, as on other occasions, they exhibited the utmost unscrupulousness as to the means by which a desired end should be accomplished.” Brownell conveys admiration for Pequot braves who “were slain fighting bravely to the last” and regret that “women and children were distributed as servants among the colonists or shipped as slaves to the West Indies.” He also remarks: “It is satisfactory to reflect that these wild domestics proved rather a source of annoyance than service to their enslavers.”[6]

Charles DeWolf Brownell, Indian Tomahawk, Kettle, Spoon, Pipe, &c. From Brownell, The Indian Races of North and South America (Boston, 1853) p. 24

Brownell’s chapter on New England Indians includes observations about the English colonists’ acquisition of native land in the Lyme region. The destruction of the Pequots “left a large extent of country unoccupied, to no small portion of which Uncas laid claim.” He and his sons Owenoco and Attawanhood later made deeds and grants “to various individuals among the white settlers, and for various purposes,” even though the effects of those conveyances “were probably unknown to the grantors.” Brownell found it “pitiful to read of the coarse coats, the shovels, the hoes, the knives, and jews-harps, in exchange for which they had parted with their broad lands.” He also observed that the titles Uncas left to his “extensive domains” resulted in “inextricable confusion.” When “the same tracts were made over to different persons,” contradictory claims arose but inevitably resolved in the colonists’ favor.[7]

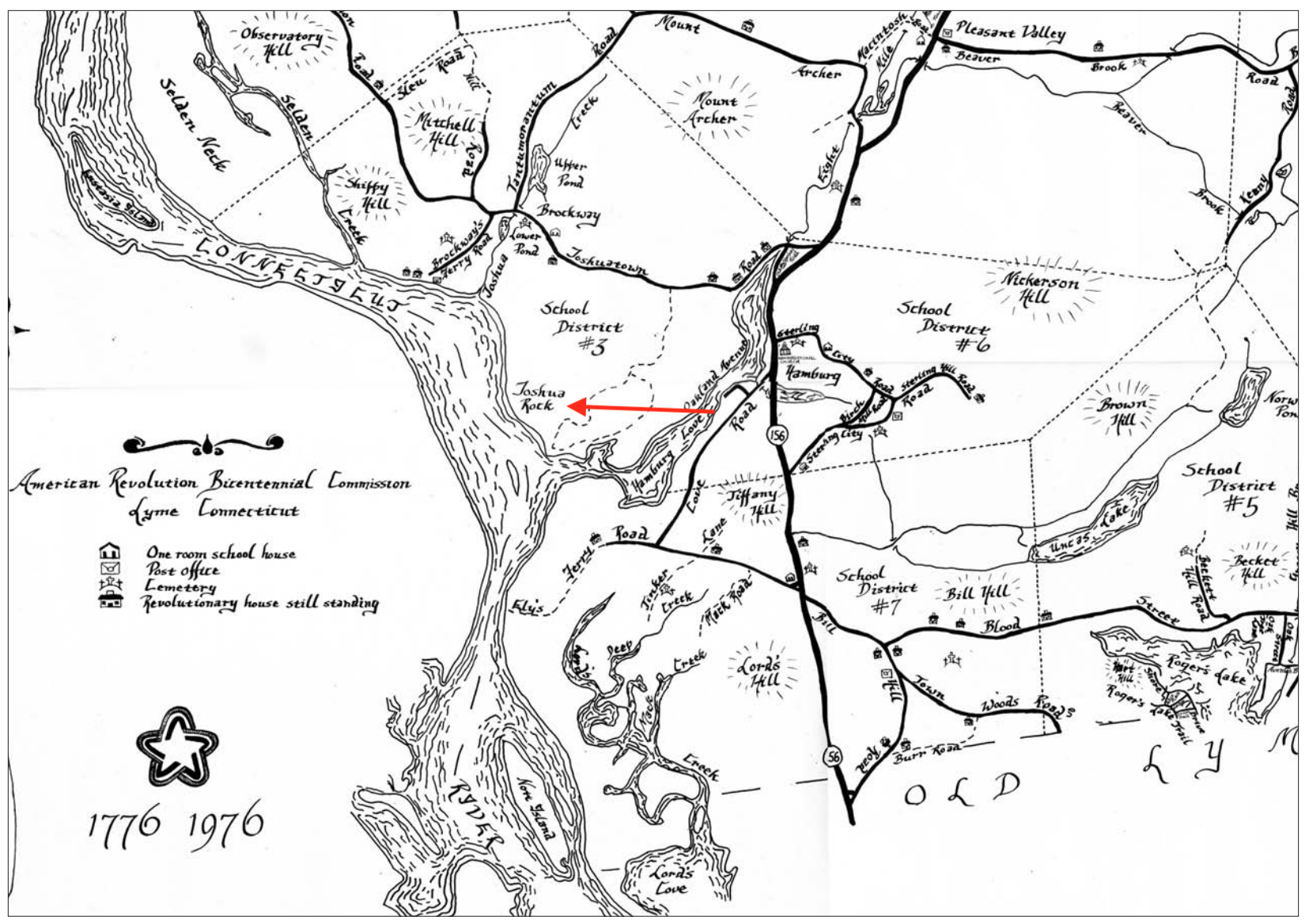

The Eight Mile River at Hamburg Cove, 1776

A will signed in Saybrook by “Joshua Sachem, son of Uncas Sachem,” in 1675 when he was “sick in body but of good and pefrect memory,” states that he was then “living nigh Eight Mile Island on the River of Connecticut and within the bounds of Lyme.” The will details the extravagant and ambiguous bequests of land that Attawanhood made to some fifty English colonists. Those bequests included 4,000 acres to Richard Ely (1610–1684) and 2,000 acres to William Lord (1618–1678), both of whom had already acquired extensive property in Lyme.[8] An eight-mile square tract extending east from Eight Mile Island that William Lord acquired from Uncas’s kinsman Chapeto in 1669 included the cliffs Charles Brownell painted almost two centuries later. Chapeto and Uncas had reserved for themselves and their heirs hunting and fishing rights and timber for canoes in what is today’s Eight Mile River scenic watershed.[9]

Charles DeWolf Brownell, View from Joshua Rocks. Private collection

Landscape and Heritage

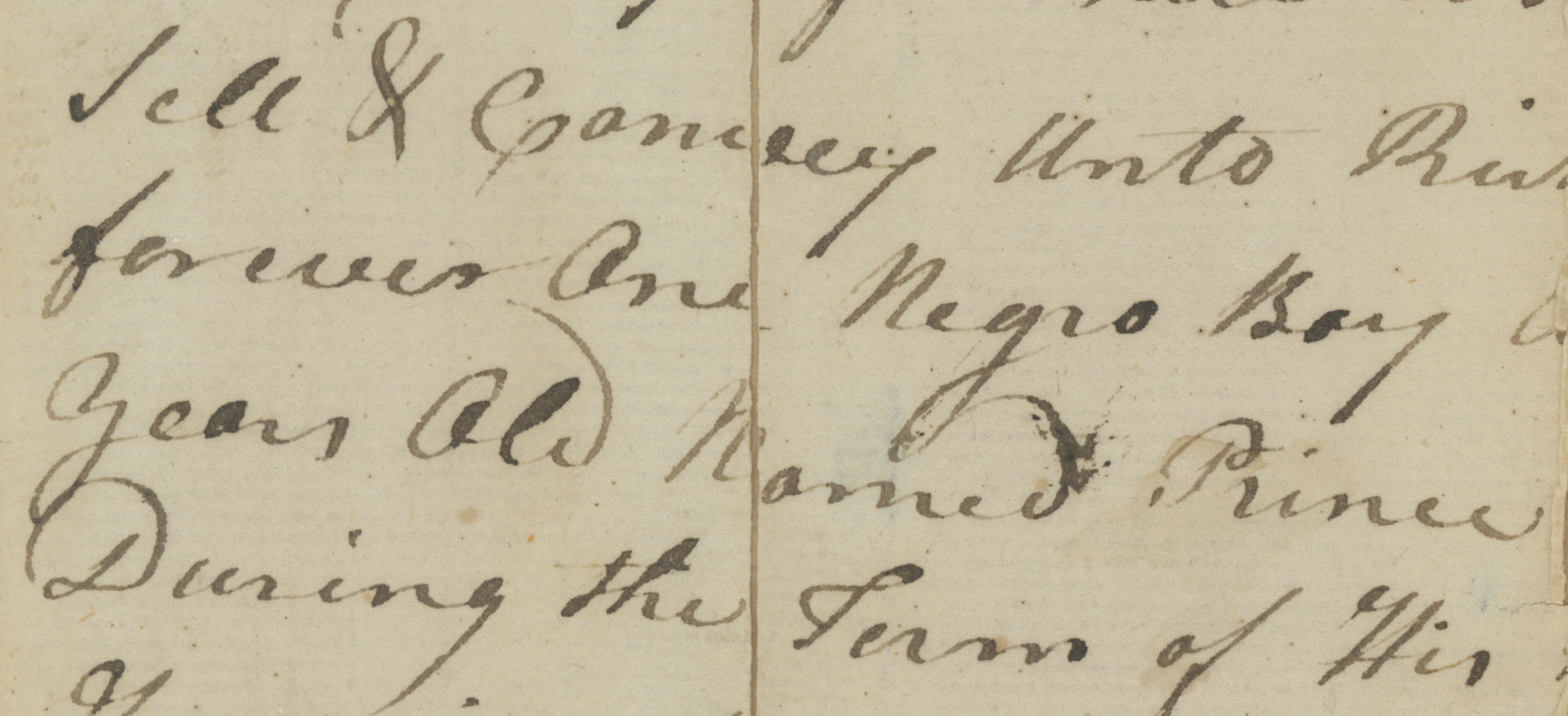

Charles Brownell’s watercolor sketch of Joshua’s seat reflects not only his historical understanding of Native American presence in Lyme but also his personal connections to the town. His ancestor Balthazar DeWolf (ca. 1621–1696) had settled in Lyme soon after its “loving parting” from Saybrook in 1665, and the town granted permission in 1681 to Balthazar’s son Edward DeWolf (1646–1712) to operate a sawmill on the Eight Mile River in exchange for providing and sawing “all the timber” for the frame of a new meetinghouse. The sawmill also provided an opportunity to produce barrel staves for the prospering West Indies trade. Edward DeWolf’s enslaved African American servant Mingo was said to be “industrious in his master’s business.”[10]

Charles DeWolf Brownell, View of Lyme, Connecticut, 1863. Watercolor on paper. Private collection

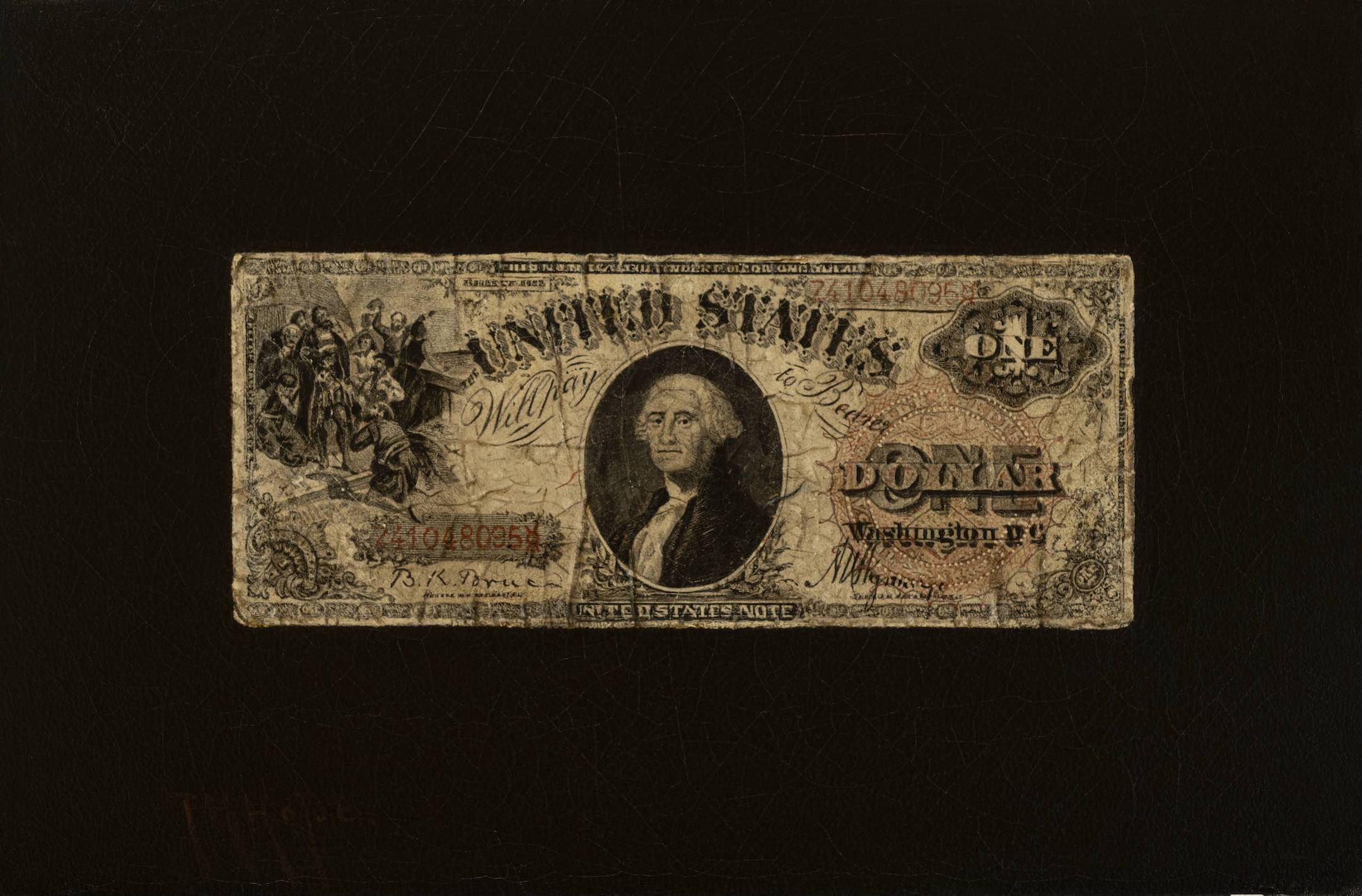

The profitability of the West Indies trade led Edward’s grandson Charles DeWolf (1695–1726) to leave Connecticut as a young man and settle as a merchant and millright in Guadaloupe. The DeWolf family subsequently played an essential role in the northern slave trade, transporting thousands of African captives to sell at auction in places like Havana and Charleston. Charles DeWolf’s descendants, who operated their slave trading business from Bristol, Rhode Island, amassed huge wealth. In about 1820, two years before Charles Brownell was born, a voyage of the brig Macdonough that transported 400 Africans earned a profit of some $100,000 for his mother’s brother George DeWolf (1778–1884), who used the proceeds to purchase a coffee plantation in Cuba where enslaved Africans labored.[11]

Attributed to Charles DeWolf Brownell, Cuban Sugar Plantation, ca. 1850s. Courtesy of William Reese Company

During the decade that Brownell painted the Lyme landscape in summer and autumn, he spent seven consecutive winters in Cuba sketching in that tropical setting while living on sugar and coffee plantations owned by members of his family. Cuba did not abolish slavery until 1886, and the view of a working sugar plantation attributed to Brownell shows a stately white house on a hill with enslaved people outside a shed where steam belches from a chimney. When Brownell married at age 43 in 1865, he moved to Bristol, where the imposing homes built by his relatives reflected their wealth and influence. Near the end of his life, he contributed his recollections of family traditions to a genealogy tracing the descendants of “Balthasar DeWolf of Lyme,” which unfolds an admiring account of the wealth and power of Rhode Island’s “princely merchants.” The author, a relative, describes the family’s slave trading as a “justly discredited pursuit” but claims that at the time “generally public sentiment was with them.”[12]

“The Mansion,” later called “Linden Place,” designed by architect Russell Warren in 1810 for George DeWolf, Bristol, Rhode Island. Historic American Buildings Survey, Arthur W. Leboeuf, photographer. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

The Florence Griswold Museum’s upcoming Fresh Fields exhibition provides new perspectives on the bucolic Old Lyme setting that visiting metropolitan artists celebrated. Charles Brownell’s evocative sketch of Joshua’s Seat offers a tranquil view in a muted palette of the legendary granite cliffs along the Connecticut River, but it also reminds us of the historic presence of native people in the scenic landscape. The family ties that drew Brownell to the town where his ancestors settled and to the tropical island where they prospered offers an additional perspective on the settings he sketched and painted.

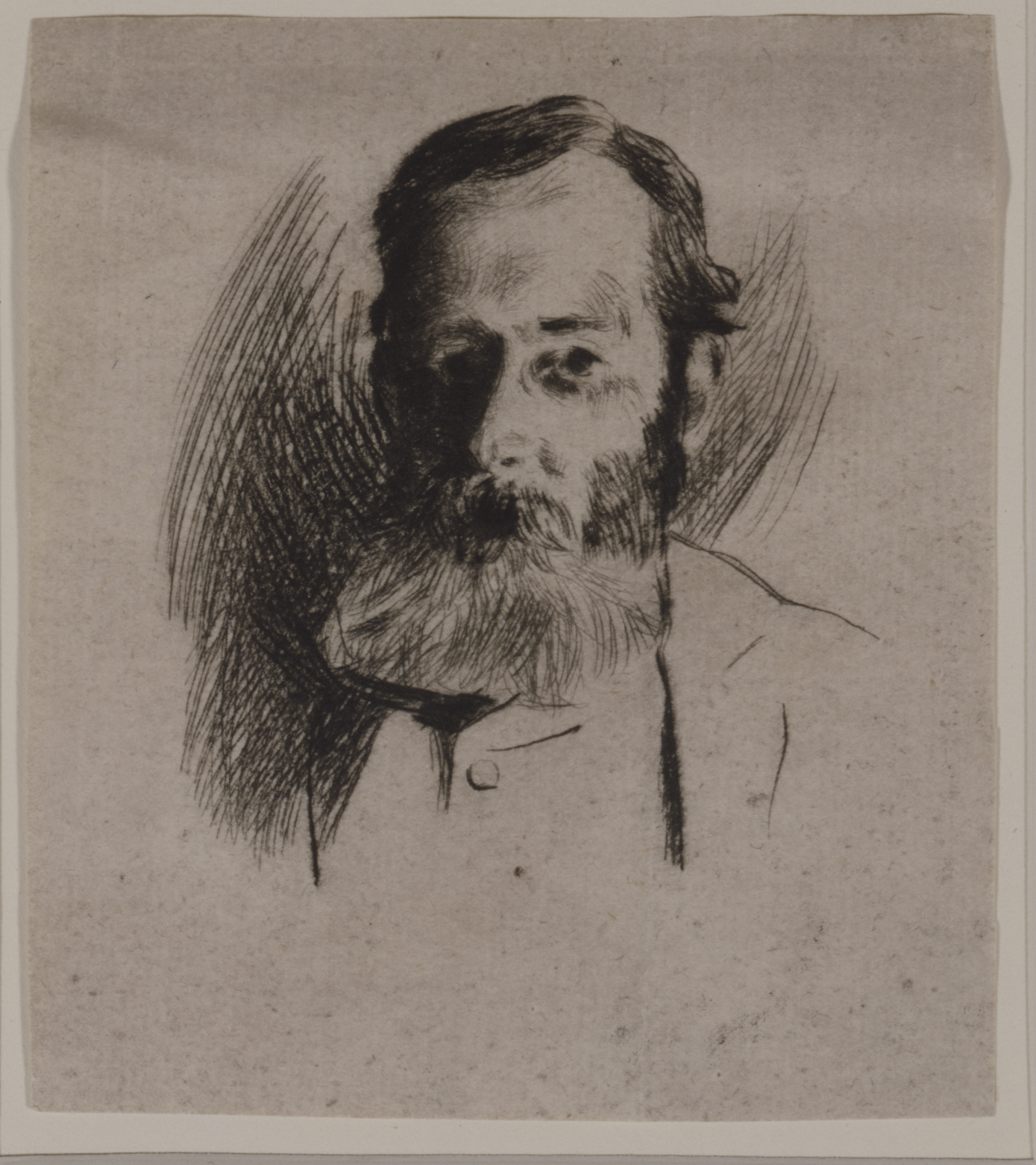

Portrait, Charles DeWolf Brownell, from H.W. French, Art and Artists in Connecticut (Boston, 1879), 119.

[1] Zebulon Reed Brockway, Fifty Years of Prison Service: An Autobiography (New York, 1912), pp. 9-10; George Shattuck Selden and Elizabeth Wright Clark, Selden Ancestry: A Family History (New York, 1921), p. 122; Oscar Jewell Harvey, The Harvey Book: Giving the Genealogies of Certain Branches of the American Families of Harvey, Nesbitt, Dixon and Jameson (Wilkes-Barre, 1899), p. 77; Peter Marteka, “A Winter trip up the Connecticut River with bald eagles, an island and Joshua’s Rock,” Hartford Courant (February 22, 2019).

[2] Francis C. Wald, Historical Sketch with Family Biographies (Pennsylvania, 1890), p. 76.

[3] “Notes from Quarry and Shop,” Stone: An Illustrated Magazine 8 (December 1893–May 1894), 294; 10 (December 1894–May 1895), 90.

[4] Elizabeth Putnam, Brockway’s Ferry, Lyme, Connecticut: A History and Memoir of Brockway’s Ferry and the Joshuatown District of Lyme (Lyme, 2002), p, 2.

[5] Trinity College Bulletin (Hartford, 1906), 3:84; Harry Willard French, Art and Artists in Connecticut (Boston, 1879), pp. 118-120.

[6] Charles DeWolf Brownell, The Indian Races of North and South America (Boston, 1853), pp. 218-219.

[7] Ibid, pp. 219-226.

[8] Cited in J. R. Cole, History of Tolland County, Connecticut (New York, 1888), pp. 13-15.

[9] Edward Eldridge Salisbury and Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury, Family Histories and Genealogies (New Haven, 1892), 2:268; J. H. Trumbull and Charles J. Hoadly, eds., The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut (October, 1681), 3:93-94.

[10] Jean Chandler Burr, ed., Lyme Records, 1667–1730 (Stonington, 1968), pp. 40-41; Bruce P. Stark, Finding Aid, New London County African American and People of Color Collection. Connecticut State Library (2008).

[11]The DeWolf family’s slave trading has been widely documented. See Cynthia Mestad Johnson, James DeWolf and the Rhode Island Slave Trade (Charleston, 2014); Emma Christopher, Freedom in Black and White: A Lost Story of the Illegal Slave Trade and Its Global Legacy (Madison, 2018), p. 41; Leonardo Marques, The United States and the Transatlantic Slave Trade to the Americas, 1776–1867 (New Haven, 2016), p. 76; Theresa A. Singleton, “Landscape, Archaeology and Memory of Cuban Coffee Plantations: 1800–1860,” Proceedings of The International Congress of Caribbean Archaeology, vol. 2 (2007), p. 655; “General George DeWolf, the man who swindled a whole town,” Warwick, R. I., Digital History Project. https://www.warwickhistory.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=265:george-dewolf-continued&catid=56&Itemid=125

[12] Rev. Calbraith B. Perry, Charles D’Wolf of Guadaloupe, his Ancestors and Descendants, Being a complete Genealogy of the “Rhode Island D’Wolfs,” the descendants of Simon De Wolf, and their common descent from Balthasar de Wolf, of Lyme, Conn. 1668 (New York, 1902), pp. 58, 30.