by Charles Beal

Feature Image: Approaching Peck Cemetery from the northwest/east, showing carved gravestones, footstones, and fieldstones.

Photographs by Charles Beal, 2016

Discovery

Jedediah Peck (1748–1821) of Lyme, Connecticut, age 23, arrived at the port of New London on August 15, 1771, after a trading cruise with a Captain Dowzich in the sloop Betsey. As he walked through town, he learned from an acquaintance that both his father and his brother Peter had died ten days earlier while he was at sea.[1] He soon learned that his brothers William and Luther had also died during his voyage. The four deaths in his family had occurred within just 25 days.

The Cemetery

Scattered stones in Peck Cemetery

Today a walk in the woods near the northwest corner of Old Lyme might lead to the sight of a few stones in the distance. As one approaches, more stones become visible, and it is apparent that this is a small, ancient cemetery. Although the inscriptions are somewhat difficult to read, the gravestones are in relatively good condition for their age. Examination makes it clear that this cemetery is the final resting place of several members of a single family who died within a relatively short period of time.[2]

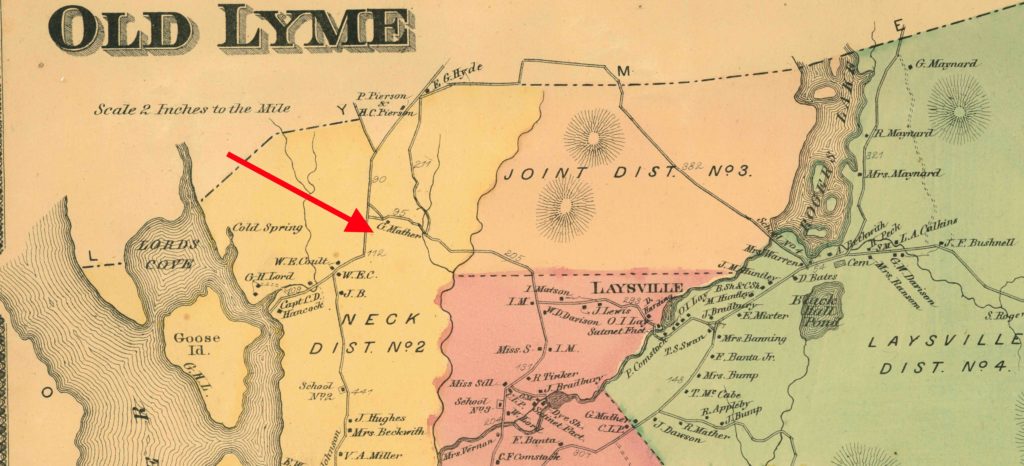

Town of Old Lyme, F. W. Beers, 1868. Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum (LHSA)

The cemetery is located on private property on the east side of Neck Road just south of the intersection with Saunders Hollow Road. The land within and around the cemetery is dry and wooded. The gravestones are enclosed by a low stone wall on the north and west sides and by more substantial stone walls on the south and east sides. Within the cemetery are several trees, including one with a girth of 99 inches estimated to be 160 years old. Two of the grave monuments are within a few inches of its trunk. The fact that a tree of this size has been allowed to develop perhaps reflects the lack of visitors interested in cemetery preservation.

View from west, showing large tree encroaching on gravestones of Elijah Peck and Peter Peck

The Peck Cemetery contains ten carved gravestones and twenty fieldstones that are believed to be grave sites. All graves with carved stones are oriented in a north/south direction with inscriptions on the north side of the headstone. Most of the graves also have footstones with inscriptions on the south side. The gravestones are mostly granite schist, and seven are believed to be the work of Gershom Bartlett (1723–1798) of Bolton, Connecticut.[3] The carvers of the other gravestones are unknown. The seven Bartlett monuments are nearly identical except for the names and dates of the deceased. The uniformity of the physical stones and their inscriptions suggest they may all have been procured and installed after the sequence of family deaths in 1771.

Hepzibah Peck headstone (top) and footstone (bottom), attributed to Gershom Bartlett

Bartlett stones are located in cemeteries throughout eastern Connecticut but are scarce in northeast and coastal communities. He is known to have produced about 675 grave stones. In addition to the Peck cemetery, his stones are found in Lyme in the Ely and Marvin cemeteries and in Old Lyme in the Laysville cemetery. Bartlett left Connecticut in 1772, moving to Pompanoosuc, Vermont, where he continued stone carving.

Bartlett gravestones have a distinctive style. Most have an arched top and round faces with bulbous noses, raised eyebrows, narrow chins, and turned-down mouths. Typically a crown sits on top of the head and wings frame the face. Four-leaf clovers, pinwheels, chains, and anchors appear in the decorative borders, and a small heart is sometimes present near the bottom of the inscription. Bartlett footstones often have diamonds cut into the stone.[4]

Gravestones of William Peck (top) and Peter Peck (bottom), attributed to Gershom Bartlett

Of the ten gravestones in the Peck Cemetery, nine inscriptions indicate a close relationship to the family of Elijah Peck (1713–1771) and Hepzibah Pearson Peck (1719–1770). The years of death range from 1759 to 1780, with four occurring in 1771.[5]

The Peck Family

Elijah Peck was born in Lyme on October 29, 1713. He was the son of Samuel Peck (1678–1734/5) and Elizabeth Lee Peck (1681–1731), who were both born in Lyme. Samuel descended from Deacon and Ensign Joseph Peck (1641–1718) and his wife Sarah Parker Peck, and Joseph’s parents were Deacon William Peck (1601–1694) and his wife Elizabeth who were both born near London, England, and came to America in 1637. William Peck was one of the founders of the colony of New Haven in 1638. Hepzibah Pearson was the daughter of Peter Pearson (1686–1750) and Mary Lord Pearson (~1692–), both of Lyme.[6]

Hepzibah and Elijah married on April 28, 1737, and over the next 25 years had 13 children. They also took in a niece who had been orphaned. Early in their marriage, Elijah moved his family for a time to East Haddam where they were living in 1742, but by 1756 they had returned to Lyme. Elijah accumulated modest land holdings.[7] He inherited land from his father Samuel and from his father-in-law Peter Pearson, and he purchased property in the area of the cemetery. In 1770 Elijah and Hepzibah lived in a house, no longer standing, on the west side of the highway that joined the North Society to the South Society.

John and Sarah Coult house, ca. 1710. Noyes-Ely Family Collection, LHSA

The Pecks’ neighbors to the south were the Coult family, and two of the early Coult houses survive. The house of Captain John Coult (1658–1751) and Sarah Lord Coult (1678–1718), located on the east side of the highway, was built in about 1710. On the west side of the highway at Tantummaheag Road stands another John Coult house dated 1760.

Elijah and several of his sons were farmers and also tanners who processed animal hides into leather for use as shoes, boots, work aprons, harnesses, clothing, and gloves. Tanning was an honorable and essential trade, but it was also hazardous, and tanners were known to have poor health and short lives. A tanner in Lyme would be licensed by the County Court in New London after serving an apprenticeship of about five years. In June 1759 licensed tanner Elijah Peck certified the application of the Separatist minister Daniel Miner (1737–1799), who in turn certified the application of Elijah’s son, Elijah Peck, Jr.[8]

On September 26, 1770, Elijah Peck, at age 56, prepared his will, stating that he was “sick and weak of body but perfect of mind and memory.” He provided for his wife Hepzibah, gave land and buildings to his sons, and left to his daughters money and land in Nova Scotia inherited from Peter Pearson.[9] On October 9, 1770, three weeks after he signed his will, Hepzibah died at age 51, leaving the ailing Elijah with young children. Three months later, on January 8 1771, he married the widow Jane Watrous Miner (1719–1811).

During Jane’s brief marriage to Elijah, she and the Peck daughters were most likely involved with caring for very sick people as well as young children. Elijah’s son William died on July 16, 1771, at age 21. Elijah, age 57, and his son Peter, age 27, both died on August 6, 1771. Three weeks later his son Luther, age 19, died on August 27, 1771. The deaths occurred in the heat of the summer, but there were no known epidemics in Lyme that year. The cause of the Peck deaths has not been discovered, but local historian Elizabeth Plimpton speculated that the family fell victim to dysentery.[10] The only survivors in the Peck household were three women, a son who was away at sea, and a nine-year old boy.

Elijah Peck in his will named his sons Peter and Jedediah as executors, but since Peter died on the same day as his father, the duty fell to Jedediah. At the time of his death, Elijah was in debt, and his moveable assets consisted mainly of household items and farm equipment. He also owned cows, a pair of oxen, one heifer, two yearling steers, 28 sheep, and a horse. Proceeds from liquidation of those assets were insufficient to resolve the claims, so Jedediah petitioned the court and received permission to liquidate property to settle the claims. It seems likely that Jedediah at that time purchased seven gravestones for his immediate family members.

After the sequence of deaths, Jedediah married Tabitha Ely (about 1755–1852) in 1772. Largely self-educated, he had a taste for mathematical studies, and instructed young men in Lyme in navigation and surveying, then served in the Revolutionary Army for at least three years. In 1790, at age 42, he moved with his family to Burlington, New York and later had a distinguished career as a judge He served for a decade in the New York assembly and the State Senate and is credited with being instrumental in founding the free public school system in New York State. “Knowledge in the people is absolutely necessary to support Representative Government, but ignorance in them overthrows it,” Peck declared.[11] He is buried in the Peck Cemetery in Burlington.

Gravestone of Jedediah Peck, Burlington Cemetery, Otsego County, New York, http://nyshmsithappenedhere.blogspot.com/2016_08_01_archive.html

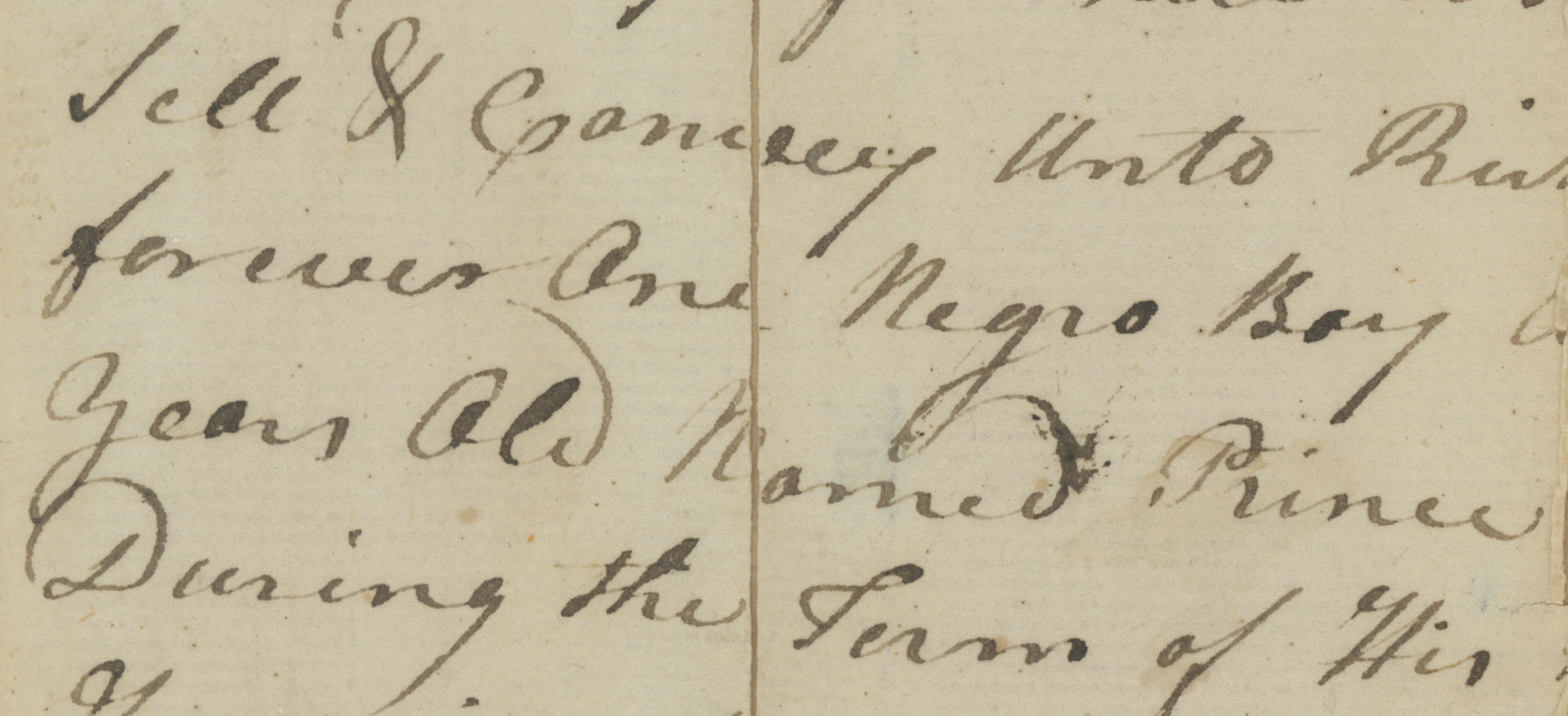

Records in Stone

The graves of the five Peck family members who died in Lyme in 1770 and 1771 are all marked with stones attributed to Gershom Bartlett. The cemetery also contains Bartlett stones for two other Peck children who died earlier, Elizabeth in 1759 just prior to her first birthday, and Elijah, Jr., in 1766 at age 23.

Gravestone of Elizabeth Peck, attributed to Gershom Bartlett

Gravestone of Mary Peck (Murphy) Lacy, unknown carver

Gravestone of John Johnson, unknown carver

Gravestone of John Johnson, unknown carver

Three gravestones in the cemetery are the work of different carvers. They mark the passing of a grandson in 1780, a married niece Mary Peck Lacy in 1771, and one person John Johnson who died in 1817 and seems unrelated to the Peck family. The identities of those buried beneath the ten fieldstones set off to the south of the main cemetery are unknown. The Pecks suffered a number of infant deaths early in their marriage and may have marked those graves with fieldstones.

Peck Cemetery, viewed from the east

The present day visitor to the Peck Cemetery, more than 245 years after Elijah Peck and three of his sons died in a single summer, can clearly see the sad story memorialized in a forgotten graveyard. They can also appreciate the unique gravestones that reflect the artistic talent of the renowned stone carver Gershom Bartlett.

[1] Throop Wilder, “Jedediah Peck: Statesman, Soldier, Preacher,” New York History 22 (July 1941), 290-300. Thanks to Linda Alexander, Head of Information Services, Old Lyme-Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library, for her research assistance; to Dr. Eileen Fuery, a direct descendent of the Peck family, who shared her research material and portions of her personal family history; and to Douglas and Maureen Lopresti for their assistance in providing access to the cemetery site.

[2] For details about Peck family members, see George Chalmers McCormick, John Kitchel and Esther Peck: Their Ancestors, Descendants and Some Kindred Families (Fort Collins, 1913), pp. 63-5.

[3] See James Slater, The Colonial Burying Grounds of Eastern Connecticut and the Men Who Made Them (Memoirs of the Connecticut Academy of Arts & Sciences, Vol. XXI, 1987), p. 16.

[4] Ibid., p. 15.

[5] The Hale Report, ca. 1934, was very helpful in researching the Peck Cemetery, but it lists the small stone now with a broken edge as the grave of “Peck, Josiah, son of Jedediah and Tabitha, died Sept. 20, 1780, age 3 wks.” Research of archival documents indicates that this is actually the grave of Elijah Peck, son of Jedediah Peck and Tabitha Ely Peck and grandson of Elijah and Hepzibah Peck. The Hale Report lists Elijah, Jr.’s, year of death as 1776, rather than 1766, and makes two errors in ages at death.

[6] See Darius Peck, A Genealogical Account of the Descendants in the Male Line of William Peck, One of the Founders, in 1636 of the Colony of New Haven, Conn. (1877).

[7] Susan Hollingsworth Ely and Elizabeth Plimpton, notes on Peck family, Lyme Historical Society Archives.

[8] Bruce P. Stark, Lyme, Connecticut: From Founding to Independence (1976), p. 52.

[9] Probate records, Connecticut State Library; Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut (May 1772), pp. 618-9.

[10]Alan Taylor, “The Plough-Jogger: Jedediah Peck and the Democratic Revolution,” in Alfred F. Young, et. al. Revolutionary Founders: Rebels, Radicals, and Reformers in the Making of a Nation (New York, 2011), pp. 375-395); George S. Sill, Genealogy of the Descendants of John Sill (Albany, 1859), p. 84.

[11] New York State Historical Markers: “A Man of “Public Usefulness” and “Private Worth.” http://nyshmsithappenedhere.blogspot.com/2016_08_01_archive.html