by John E. Noyes

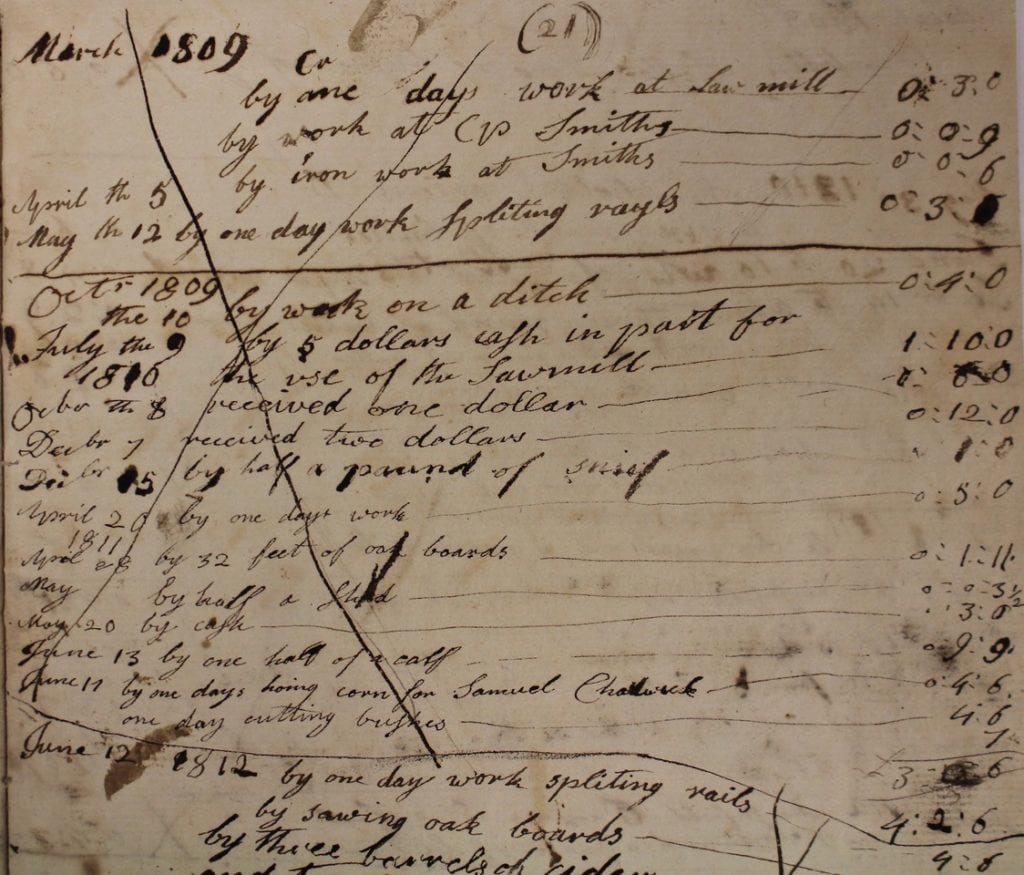

Featured Image: Elisabeth Marvin Account Book, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum (LHSA)

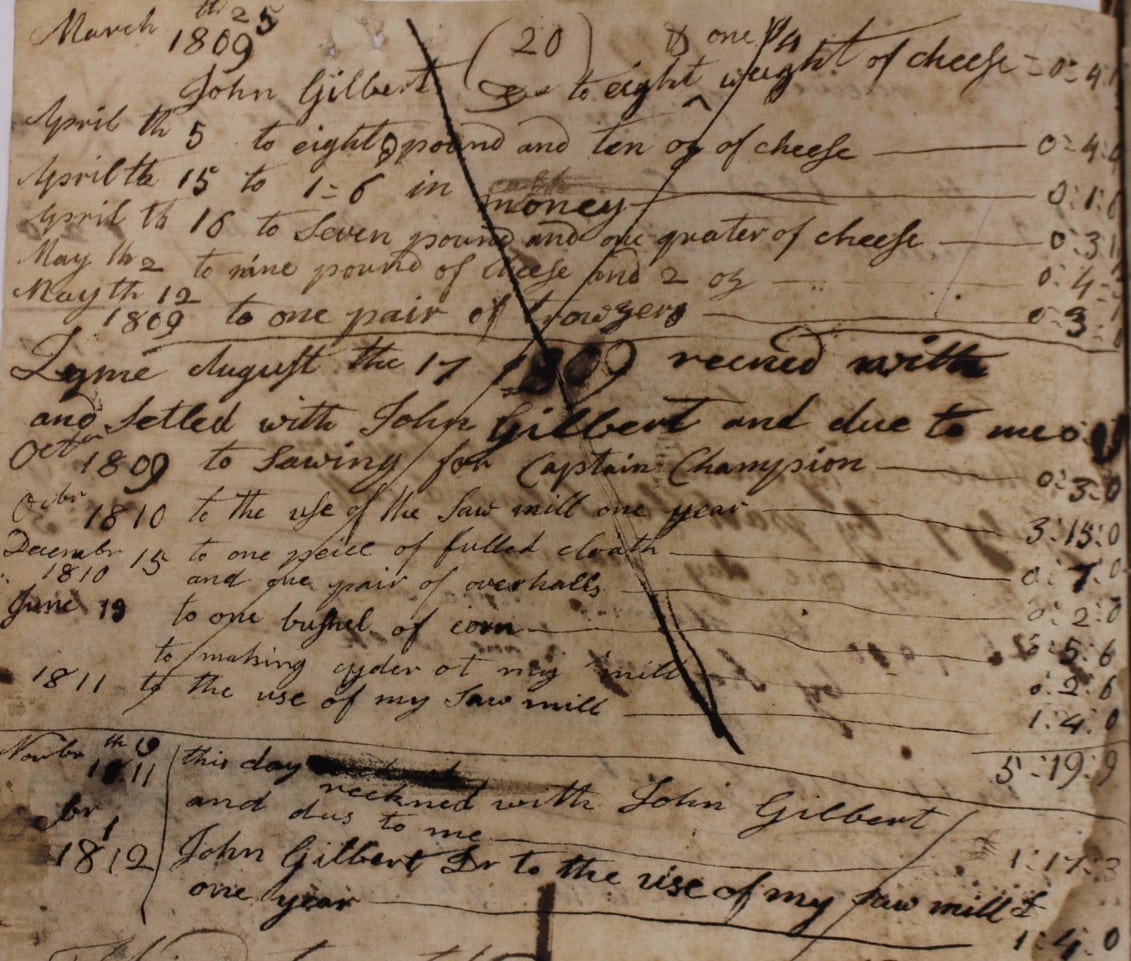

The Florence Griswold Museum’s Lyme Historical Society Archives house several old business account books, which provide insights into Lyme’s early years. Here is a glimpse at the records of Elisabeth Marvin, who was probably the widow of Matthew Marvin, inheriting his business when he died on August 29, 1806, at age 64. Elisabeth was 60 when Matthew died; she would live until 1839. Her account book entries run from September 1806 to October 1825, ending the month after the death of an unmarried daughter (also named Elizabeth), who may have helped her mother with the family business.

What can we glean from Elisabeth Marvin’s account book? First, it shows us some of the goods and services important to life in Lyme. Page 20 (above) records that, from March 1809 to February 1812, Marvin sold John Gilbert a lot of cheese, a bushel of corn, “one pair of trowzers,” “one peice of fulled cloth,” and “one pair of overhalls”; loaned him a small amount of money; and contracted for Gilbert to use “my” saw mill and cider mill.

Second, goods were not always sold for cash, but were often bartered for other goods and services. Look at page 21, where Marvin recorded how Gilbert paid for his purchases. He paid partly with goods: half a shad, half a calf, oak boards, and three barrels of cider. Gilbert also provided various services, which Marvin credited to his account: splitting rails, digging a ditch, cutting bushes, doing iron work, working for Marvin at her saw mill, and “hoing corn for Samuel Chadwick,” to whom Marvin may have owed a debt.

Elisabeth Marvin Account Book, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum (LHSA)

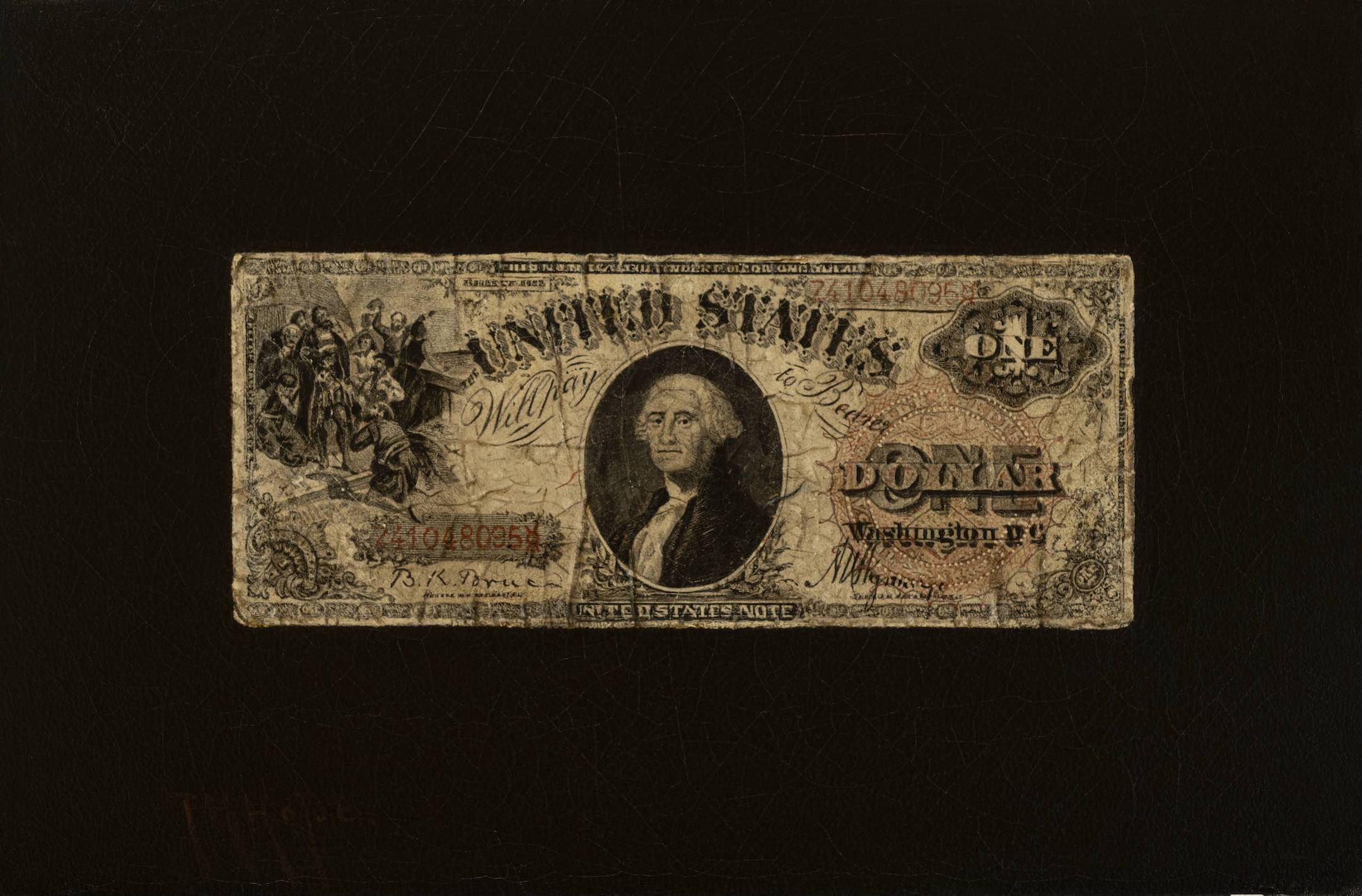

Third, more than three decades after America declared its independence from Great Britain, Marvin recorded transactions in British currency, even translating Gilbert’s several dollar payments into pounds, shillings, and pence. The storekeeper Jonathan Gillet also used British currency in his account book, which covers the years 1771-1786. This practice may have reflected the weakness and inflation of early U.S. currency. Marvin herself began to record transactions in dollars in 1817. That year marked the opening of the Second Bank of the United States, a federal institution intended to promote currency stability.

Fourth, Marvin’s account book tells us something about the relative value of goods and labor in the early 1800s. A pair of overalls cost Gilbert two shillings, while a day’s labor profited him at most five shillings. A shilling in 1810 would be worth about four dollars today.

Fifth, Marvin often spelled phonetically, and her spelling and capitalization differed even on the same page. Gilbert received credit both for “Spliting rayls” and “spliting rails.” Such inconsistencies were common among literate people. Standardized spelling gradually took hold later in the 1800s, as the use of dictionaries became more common.

Even this brief look at Elisabeth Marvin’s account book prompts one to think about a range of issues: writing and literacy, currency stability, and the economy in a small town such as Lyme. One wonders too about the location and operation of local mills, the skills of laborers, farm life, and the production of various goods.