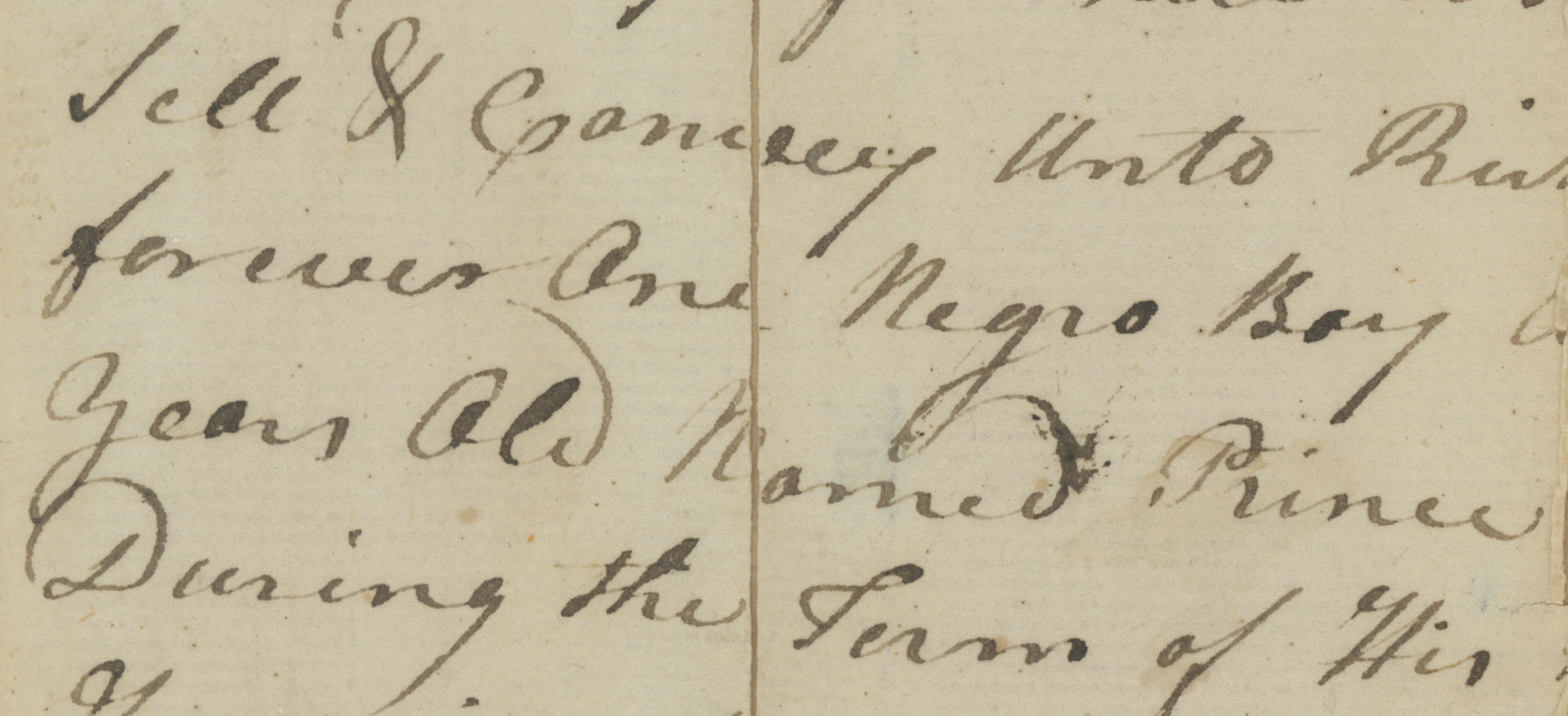

by Carolyn Wakeman

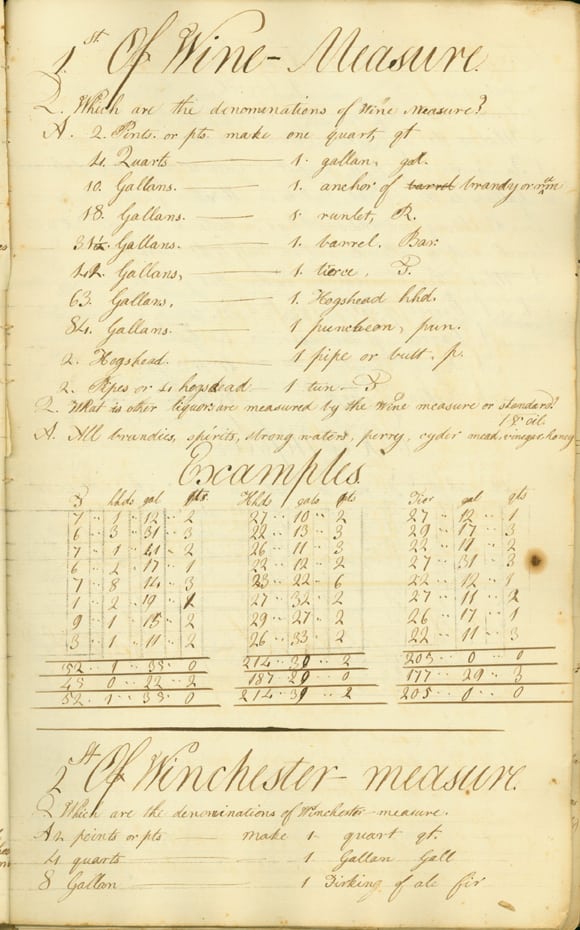

Featured Image: William E. Coult’s Book (n.d.), showing arithmetic lesson on measures of wine. Coult Papers, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

To understand units of measurement no longer in use while studying an account book, I relied on an elegant arithmetic textbook handwritten by William Coult and preserved in the Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum. Early Lyme account books itemize rum, an important commodity in the West Indies trade, by the hogshead, and “William Coult’s Book” taught me that a barrel held 31 1/2 gallons and a “hhd” contained 63 gallons. The Museum’s recent exhibition Pen to Paper: Artist’s Handwritten Letters from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Artdrew me back to Mr. Coult’s math book. I wanted to see how the art of penmanship developed in Old Lyme.

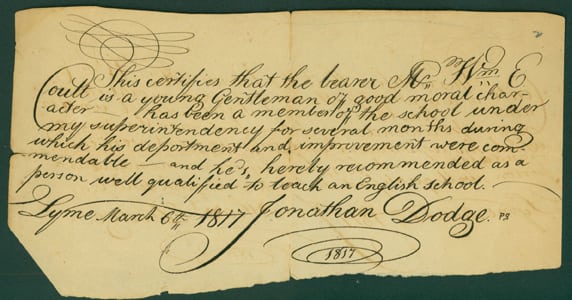

William Coult, certification as teacher (1817). Coult Papers, LHSA at FGM

William Ely Coult, born in 1797, lived in the section of town called Tantummaheag in a comfortable farmhouse built by his father near the Connecticut River. He attended the nearby Neck Road district school and received certification as a teacher at age 20. He used a sharpened, ink-filled quill pen to compile, or perhaps copy, his math text, and he shaped both words and numbers with precision and flair. I wondered if the handwriting in his younger step-sister Nancy Coult’s school copybook, dated 1822 when she was 14, reflected his guidance. On one page Nancy repeatedly copied an inspirational sentence: “Prayer should be the key of the day and the lock at night.”

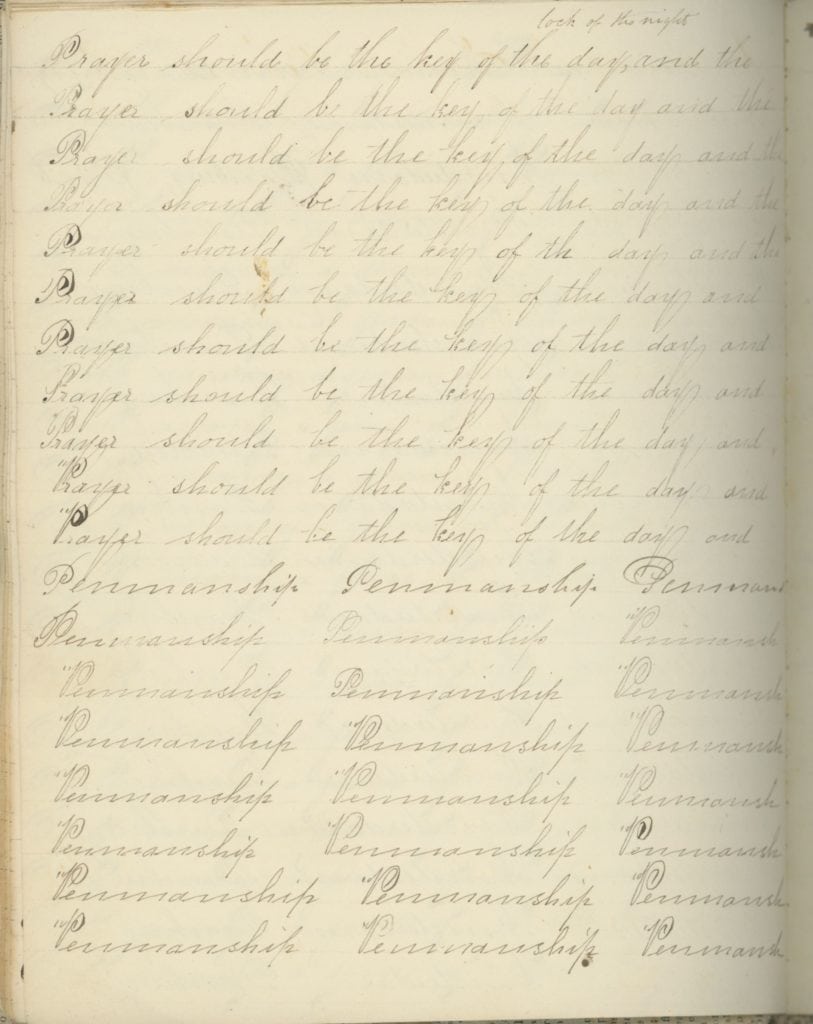

Nancy Coult, copybook (1822). Coult Papers, LHSA at FGM

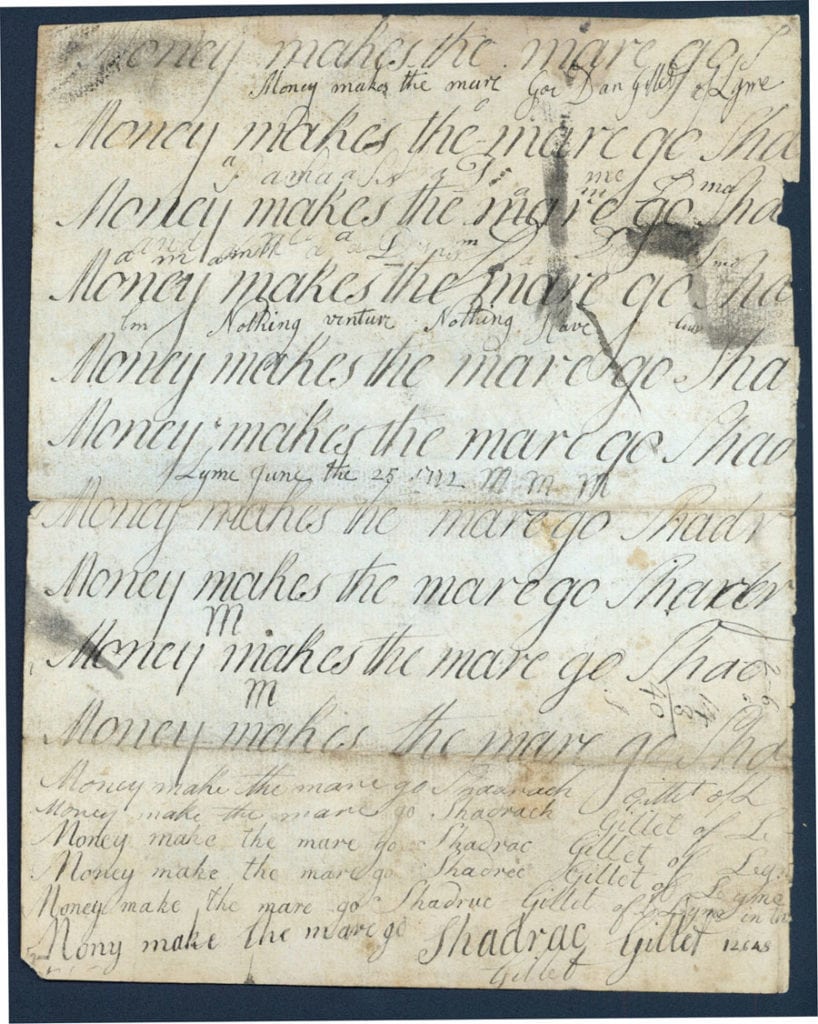

Penmanship practice in the public schools taught the careful formation of letters, but it also provided moral instruction to impressionable students who filled line after line with motivational statements. Half a century earlier Dan Gillet, age 14 and a student at the district school on Grassy Hill, copied two sentences in his notebook on June 25, 1772: “Money makes the mare go” and “Nothing Venture nothing have.” Three years later Dan marched to Boston with other militia members from Lyme, mostly young farm boys who faced seasoned British soldiers laying siege to the city.

Dan Gillet, copybook page (1772). Gillet Papers, LHSA at FGM

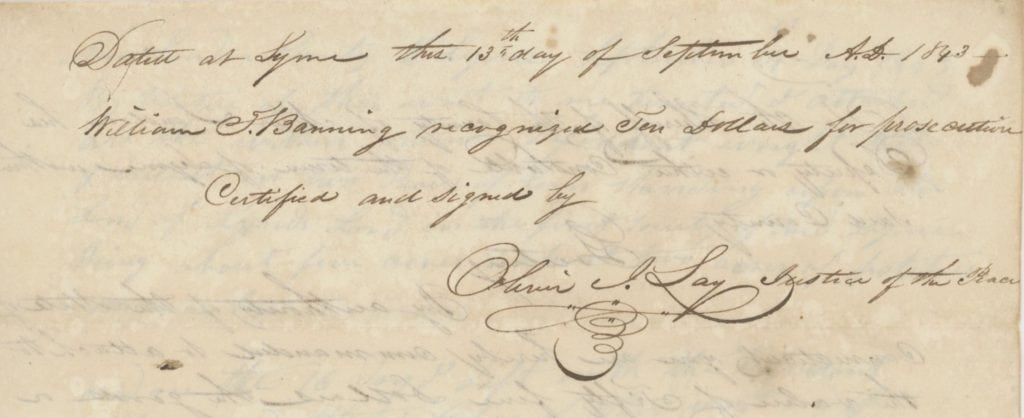

In the 1840s a penmanship teacher in Ohio named Paul Rogers Spencer popularized a more elegant script than the “modified round hand” that Dan Gillet practiced before the Revolution. “Spencerian script” was even more elaborate and embellished than the graceful penmanship style William Coult used in his textbook. Spencer’s widely publicized method likely influenced the handwriting of Justice of the Peace Oliver Ingraham Lay, who routinely included graceful curlicues when he wrote legal decisions and also when he entered property transactions in the town’s land records.

Oliver I. Lay, Case of William F. Banning (September 13, 1843). Lay Papers, LHSA at FGM

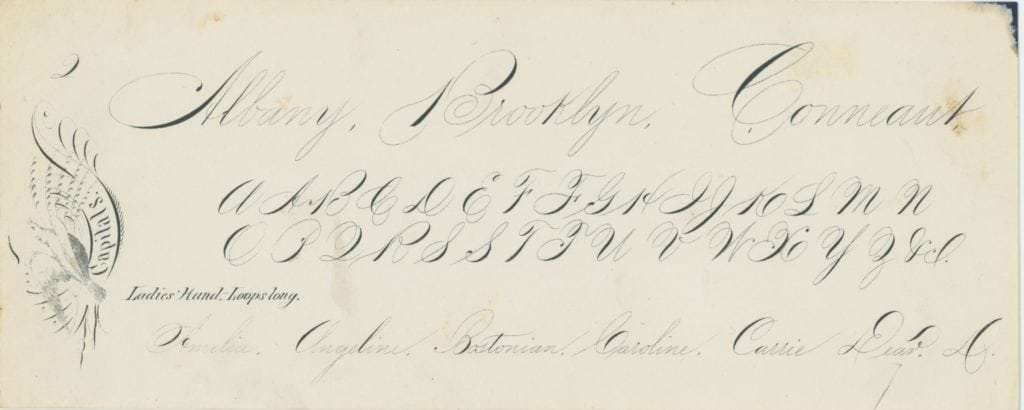

William Coult’s widow wanted to pass on the art of penmanship to their only son. Among the Coult family papers I found an elaborately decorated envelope containing fourteen printed samples of “elegant handwriting” marketed in 1879 by Paul Spencer’s student George Gaskell. William Coult had died two years earlier at age 79, and Ernestina Fisher Coult, whom he married late in life, sent their children to the town’s best private schools. She must have bought the set of mail-order handwriting samples for Willie F. Coult when he was 12. On the envelope he wrote his name in pencil alongside the date 1883.

Gaskell’s Compete Compendium of Elegant Handwriting (1879). Coult Papers, LHSA at FGM

An earlier article available on the museum’s history blog unfolds the story of William Coult’s marriage to Ernestina Fisher, a young immigrant from Germany who worked as his mother’s household servant. To read more about Lyme’s one-room district schools and about early student enrollments and teacher requirements, glance through May Hall James, The Educational History of Old Lyme, Connecticut, 1635-1935(1939), available in the Museum’s library. Tamara Plakins Thornton’s Handwriting in America: A Cultural History (1998) explores the many ways that handwriting since the colonial period reflects social changes.