Hauling and Harrowing

Rural and Urban Relationships

- The Museum will be closed Sunday, April 9 in observance of Easter.

Home | Biography | Volkert’s Work | Historic Footage | Timeline | Scrapbook

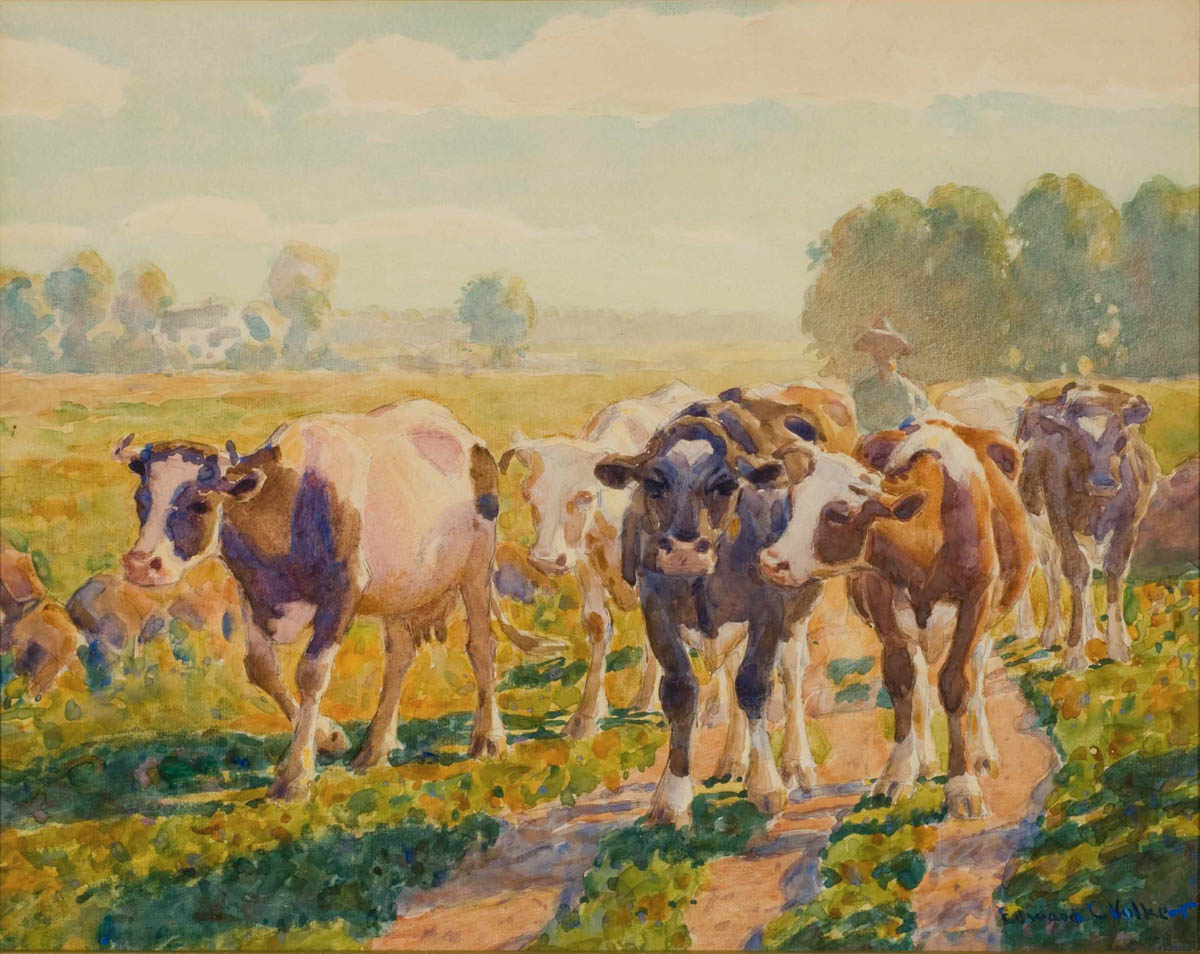

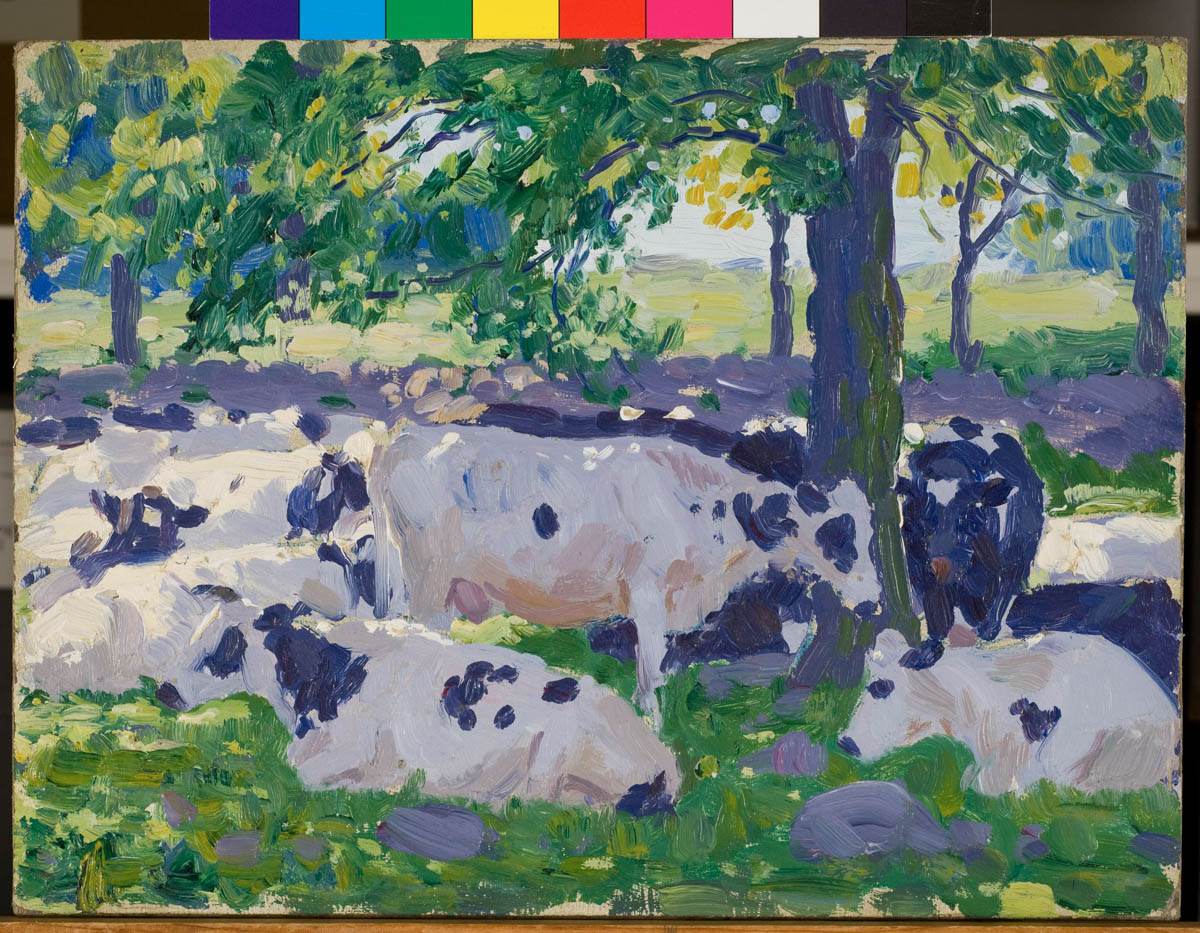

Edward C. Volkert’s paintings of livestock and farmers celebrate New England rural life. The rolling landscapes, gentle streams, stone walls, and pastures on his canvases, all sparkling under brilliant illumination, depict country spaces as picturesque and wholesome. While grounded in observations of Lyme’s farms and farmers, Volkert’s idylls spoke to audiences in cities—by 1920 home to the majority of the U.S. population. These people were the main consumers of his paintings, which offered them tranquil visions that contrasted with the bustle and tensions of urban life.

Although completed in his studio on Lyme’s Sterling City Road, Volkert sent his paintings to exhibitions in New York, Philadelphia, Washington, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, St. Louis, San Francisco, and beyond, with some of them entering collections in the cities where they were shown as examples of contemporary, albeit traditional, American art. The artist himself circulated between city and country, spending summers in Lyme, winters in Cincinnati, and periods in New York where he participated in professional clubs and exhibitions.

Volkert’s own seasonal presence in the country reflects the relationship to rural areas held by more and more urbanites in the 1920s. Farms, like those in Lyme, became vacation destinations for cityfolk, made accessible by the explosion of car ownership after World War 1. Income from tourist boarders on farms became an ingredient in the survival of Connecticut agriculture, and around New England. For visitors considering a rural getaway, Volkert maintains a fantasy of country life, depicting cattle roaming over pastures or streaming across dirt roads without regard to automobiles carrying ever more traffic and tourists.

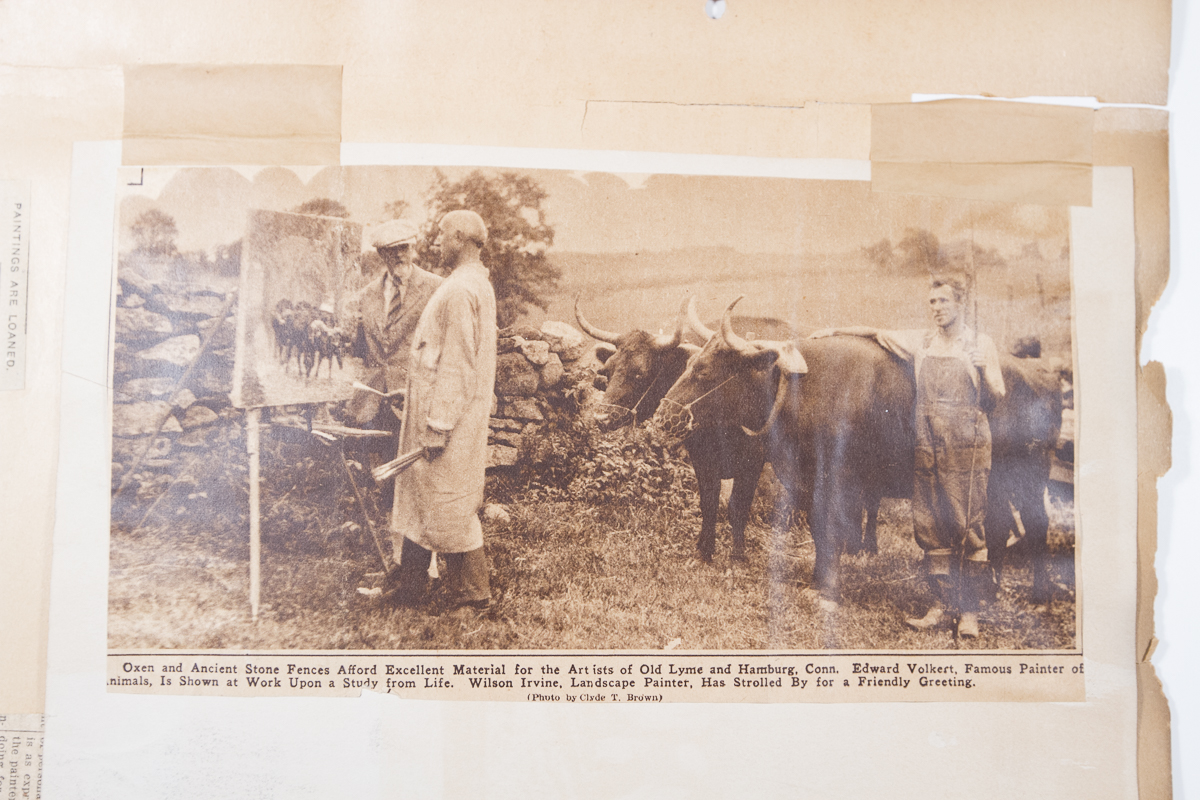

Volkert himself had arrived in Lyme as one of these tourists, describing to a reporter how he “had been there sketching and one afternoon I came across a little uninhabited cottage situated on a southern hillside overlooking a broad valley; it was exactly what I had always wanted to possess. There were two old barns that easily could be turned into wonderful studios and I purchased it at once.”(1) At the same time, the credibility of Volkert’s rural paintings for an urban audience was built on the artist’s embrace of country life. The artist was described as “a worker,” out at “the stroke of three,” which found him “afield in search of the dawn and its quickly fading mists and shadows.”(2) “Judging from his canvases,” one journalist surmised, “one would say the man behind them is a ruralite—he seems to have turned his back on urban things. The drowsing, browsing cattle, the blue sky, the shadow-flecked hillside seem Mr. Volkert’s native haunt.”(3) “The farmer, his oxen and cattle, his daily life of toil seem to be the Volkert creed, but as with Millet, the paintings are the simple and natural expression of the artist’s feeling for rustic life.”(4) Like other Lyme residents, the artist grew a vegetable garden, writing to his Cincinnati relatives about its progress and his desire to submit better produce than his neighbors to the annual Hamburg Fair. Constructing himself as “a ruralite,” Volkert cultivated a reputation for authenticity based on his knowledge and ability to portray rural life. Leaving nothing to chance, he publicized his reliance on farmers like Lyme’s William Marvin, who he said served as “one of the artist’s pre-exhibition jurymen,” vetting his paintings for accuracy.(5) As a member of the community, Volkert could act as a link between rural and urban that, in the view of one reporter, could reminded each of their overlooked connection to one another:

“…the typical Volkerts of today are devoted to a certain type of rustic scene that represents farm life, wherein oxen are the featured subjects. What endless toil we encounter there! Together the farmer and oxen plow great fields; together they haul sleds piled high with wood; together they harvest the crops; together they cut and stack hay; together they haul it to barns and store it for winter use. Involuntarily you think what toil and energy is expended here that all may live.”(6)

However, Volkert acknowledged that his foray into painting cattle began not in the Connecticut countryside, but in the city. Rising early to capture light effects in a landscape painting one day in 1903 near his residence in the Bronx, he approached Schneider’s dairy on Boston Road. There, he “saw a group of cattle browsing in the sunshine, which so appealed to him as a fine composition that he made a study of it….since then he has painted little else.”(7)

Perhaps one of the most significant ways in which Volkert’s paintings of cattle in the country speak to the interests of urban audiences is in their spirit of optimism. Journalists commenting on the artist’s work typically referenced Volkert’s sunny palette and placid bovines, animals seemingly without a care in the world. The Decatur Herald is characteristic, describing Volkert’s pictures as “…the embodiment of cheer.” The artist affirmed, “‘I like blue skies—they speak to all of hopefulness and good cheer,’ says the painter in simple explanation.”(8) That spirit of untroubled optimism prevailed in America in the 1920s, when new technologies and consumer goods like vacuum cleaners and electric refrigerators helped popularize the phrase, “What will they think of next?” Paintings by modern artists such as Gerald Murphy that depict recent inventions like the safety razor in streamlined forms are typically identified with this zest for life and mass consumption in the 1920s. Perhaps surprisingly, Volkert’s crafted images of rural life also radiate optimism in their intense hues, vivid light effects, and reassuring message of timeless regularity. In fact, farm life and the sector’s prosperity diminished with the Agricultural Depression of 1920-21, the opposite of such rosy idylls. They continued the slide toward the cataclysm of the 1930s, but Volkert’s paintings look on the bright side—a parallel to the optimism that fueled the credit spree, overconsumption, and reckless speculation in stocks that brought down the economy in 1929.

Footnotes

- Volkert, quoted in Mary Leonhard Ran, Edward Charles Volkert, A.N.A., 1871–1935 (Cincinnati: Mary Leonhard Ran Fine Paintings, 1983), p. 3.

- “E.C. Volkert, Painter of Cows,” Decatur Herald (Ill.), December 12, 1915, p. 26.

- Ibid.

- Unnamed newspaper article, quoted in Ran, Edward Charles Volkert, A.N.A., 1871–1935 (Cincinnati: Mary Leonhard Ran Fine Paintings, 1983), p. 5.

- “Volkert’s Unique ‘Cattle-Logs’” The Literary Digest, August 3, 1935, p. 24.

- Unidentified newspaper clipping, Volkert Scrapbook, Private Collection.

- M.L. Alexander, “Cincinnati,” American Art News, May 23, 1914, p. 7. Reference to Schneider dairy comes from Ruth Volkert Middleton scrapbook of newspaper clippings, quoted in John Fleischman, “The Man who Painted Cows,” Ohio, 7, no. 10 (January 1985), 75, and reprinted, with source given as Bronx Home News, in Mary Leonhard Ran, Edward Charles Volkert, A.N.A., 1871–1935 (Cincinnati: Mary Leonhard Ran Fine Paintings, 1983), p. 3.

- “E.C. Volkert, Painter of Cows,” Decatur Herald (Ill.), December 12, 1915, p. 26.

Farm Labor | Health & the Food Supply | Rural & Urban Relationships | Technological Change

Home | Biography | Volkert’s Work | Historic Footage | Timeline | Scrapbook