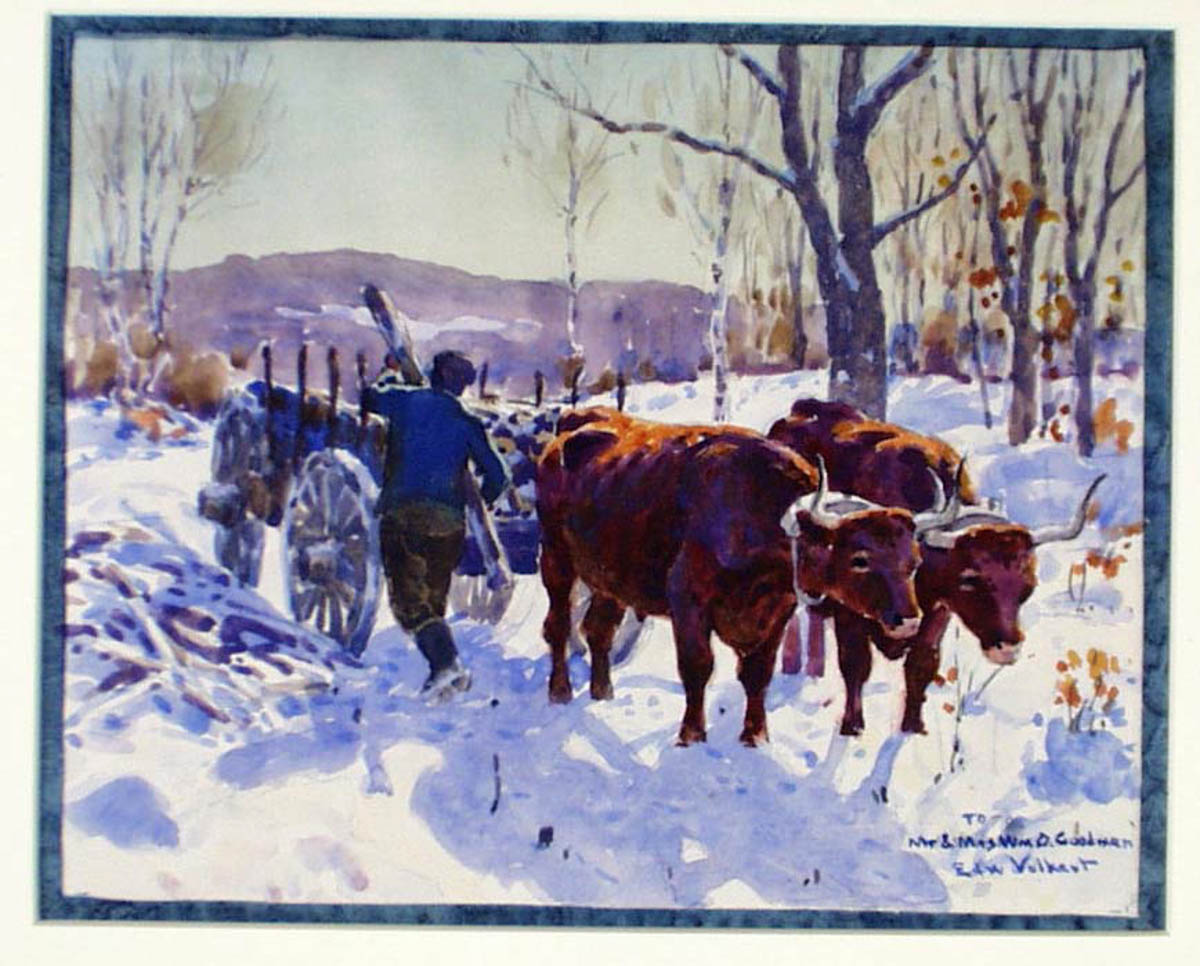

Hauling and Harrowing

Farm Labor

- The Museum will be closed Sunday, April 9 in observance of Easter.

Home | Biography | Volkert’s Work | Historic Footage | Timeline | Scrapbook

Enjoying what has been called its “golden age,” from 1910–1914, America’s farm economy continued to burgeon during World War 1, when conflict-plagued Europe relied on U.S. exports.(1) Prices for some American commodities more than doubled, leading farmers to borrow through banks created in 1916 by the Federal Farm Loan Act to pay for more efficient machinery and to cultivate additional land. Farmers took on debt to boost production, but when foreign demand and supplies needed for relief efforts or for American troops abroad declined in 1919, prices dropped. American farmers suffered economically during the Depression of 1920-21, a slide that would continue through the 1930s.

During World War 1, a shortage of male farm laborers had led to the formation of the Women’s Land Army to perform necessary agricultural work. Public information campaigns characterized the jobs as women’s equivalent contribution to the war effort, and offered up images of Europe’s women toiling at ploughs as a model. After the Armistice in 1918, the corps suspended its work, with men returning to America’s agricultural fields. Volkert’s paintings from this time reflect men’s greater numbers in farming, and stress tasks such as harrowing, plowing, or hauling wood with large animals that men, rather than women, performed on farms. The artist’s compositions often focus on a single farmer, at times with a younger assistant, rather than on a group of laborers working as a team to bring in a harvest, for example. In this way, his paintings reinforce the paragon of the yeoman farmer, an individual who owned and cultivated his own land, and ideal elevated centuries before by Thomas Jefferson. In fact, the economic crisis for farmers during the Depression of 1920-21 fostered a move toward the establishment of local agricultural co-operatives, through which farmers could make joint purchases and market their produce. Reporting about its activities in Lyme in 1922, Connecticut’s Farm Bureau cited the town farmers’ co-operative purchase of fertilizer. The move toward co-operatives feels absent from Volkert’s depiction of individual Lyme farmers.

Volkert’s focus on farm work prompts consideration of the laborers. In 1925 New London County had a farm population of 12,221, a number that includes an increase in rural dwellers from immigrant backgrounds. This growth occurred amid an overall population decline as many rural inhabitants moved to cities.(2) Immigrants bought and worked area farms, establishing communities like that of the Jewish farmers who settled in Colchester, Connecticut. In the decade after the end of World War 1, approximately 1,000 Jewish farm families moved to Connecticut, prompting a nativist backlash that paralleled suspicion of immigrants nationally in those years, resulting in the imposition of severe federal immigration restrictions in 1924. In Lyme, between 1880 and 1930, foreign-born residents increased by 187%.(3) “Yankee” farmers were portrayed by nativist commentators as a vanishing group, but Volkert’s paintings of rural workers continued to focus on his Lyme neighbors whose families, such as the Marvins and Bannings, had long ties to the area.(4)

Connecticut’s farms, like those in Volkert’s pictures, responded to changing labor conditions in the early 20th century through specialization. Without as many laborers needed for the sort of self-sufficient farming that would produce enough food and income to support a family, farmers narrowed their focus to selected areas such as meat, vegetables, shade tobacco, eggs, or dairy. Specialization also characterized Volkert’s approach to depicting those types of farms in his art—in particular his nearly exclusive attention to cattle. As a journalist put it in an apt analogy aligning art with economics, “Mr. Volkert also believes that an artist should specialize in one type of pictures the same as a merchant should specialize in one line of goods.”(5)

Farm Labor | Health & the Food Supply | Rural & Urban Relationships | Technological Change

Home | Biography | Volkert’s Work | Historic Footage | Timeline | Scrapbook

Footnotes

- Carolyn Dmitri, Anne Effland, and Neilson Conklin, “The 20th Century Transformation of U.S. Agriculture and Farm Policy.” United State Department of Agriculture, Economic Information Bulletin, no. 3 (June 2005), 7. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/44197/13566_eib3_1_.pdf

- [add this full reference when server reconnects] http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/usda/AgCensusImages/1925/01/06/1925-01-06.pdf See also, James Lowell Hypes, Social Participation in a Rural New England Town. Teachers College, Columbia University Contributions to Education, No. 28. (New York: Teachers College, Columbia University, 1927), Ch. 5. URL http://reader.library.cornell.edu/docviewer/digital?id=chla2752224#page/73/mode/1up

- Lyme’s Population Profile, 1880–1930. Blog entry, Lyme Public Hall. URL https://www.lymepublichall.org/changes-in-lymes-population-profile-1880-1930/

- See Mary Donohue and William Libo, MD, “Hebrew Tillers of the Soil, Connecticut Explored (Spring 2006). URL https://www.ctexplored.org/hebrew-tillers-of-the-soil/ . Also, Mary M. Donohue and Briann Greenfield, A Life of the Land: Connecticut’s Jewish Farmers (Hartford: Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford, 2010). For Volkert’s depictions of William Marvin, “Volkert’s Unique ‘Cattle-Logs’”, The Literary Digest, August 3, 1935, p. 24.

- Unnamed newspaper, quoted in Mary Leonhard Ran, Edward Charles Volkert, A.N.A., 1871–1935 (Cincinnati: Mary Leonhard Ran Fine Paintings, 1983), p. 12.