by Carolyn Wakeman

Featured image: Malik Naveed bin Rehman, Zahida Altaf, and daughter Roniya in sanctuary at the First Congregational Church, Old Lyme, 2018. Archival pigment print. Courtesy of the artist

The Florence Griswold Museum’s exhibition “Nothing More American:” Immigration, Sanctuary, and Community features Matthew Leifheit’s riveting photographs of a Pakistani immigrant family sequestered in Old Lyme’s Congregational Church pending the outcome of a deportation appeal. The striking black-and-white images in the first gallery capture Malik Naveed bin Rehman and his wife Zahida Altaf, owners of a successful pizza restaurant in New Britain, with their daughter Roniya, an American citizen, adapting to residence in the iconic meetinghouse for eight months in 2018. Displayed alongside luminous impressionist paintings of the historic white church, the evocative, often intimate, photographs invite reflection on the circumstances of earlier immigrants in the scenic New England town. Then, as now, immigration provoked controversy.

Famine and political turmoil in Western Europe propelled tens of thousands in the mid-19thcentury to seek safety and opportunity in the rapidly developing nation across the Atlantic. Some found their way from the port of New York to Lyme (later Old Lyme). The federal census in 1850 listed the town’s population as 2,268, which included 52 persons born in Ireland, of whom 37 were female. In a college essay the next year, Yale student Robert McCurdy Lord (1833–1894), whose ancestor William Lord (1618–1678) had acquired a vast tract of tribal land along the Connecticut River in 1667, elaborated contemporary anti-immigrant sentiment.

Charles Ebert (1873–1959), Old Lyme Church, ca. 1923. Oil on canvas. Collection of the First Congregational Church of Old Lyme

Robert’s own family employed two Irish women, May Foster, age 17, and Margaret Conniff, age 40, as domestic servants in their comfortable home near the stately white meetinghouse. “Is foreign immigration beneficial to our country?” Lord, age 17, asked in one of several essays preserved among his family’s papers.[1] “No country has ever experienced such an influx of foreign population as our own,” he declared, but “the merits and demerits of our foreign immigration have not received that attention of late which they justly demand.”

The Stephen J. Lord house, ca. 1895, had passed to his daughter Gertrude McCurdy Lord Griffin (1840–1904). Lyme Historical Society Archive at the Florence Griswold Museum (LHSA)

Lord conceded that “the coming glory of our nation consists in. . .the rapid peopling of our unoccupied territories,” but the foreign-born, he argued, congregated in “our great cities, destitute and impoverished, frequently afflicted with loathsome diseases.” They “crowd our hospitals alms-houses and dispensaries,” he wrote, “and increase the already immense burden of domestic pauperization.” Meanwhile those immigrants “who remain in our seaport towns constituting a very large proportion of our family servants and public labourers do not settle down polished to an urbane elegance of manners but invariably serve to fill our jails and penitentiaries.” Immigrants were “steeped in ignorance” and “imbued with the bigotries of Catholicism,” he declared, and they exerted “an evil undeceit (sic) upon the community around them.” Not only were their “darkened minds. . .impervious to the light of knowledge,” but their consciences were “in the hands of dominant and unscrupulous priests, by whom they may be easily won over to acts of violence, any deeds whatsoever.” The “alarming influx” of immigrants threatened “the purity of religion” as well as “the integrity of the ballot box.”

Lord had absorbed his stridently anti-Catholic views from the Congregational Church in which he was raised. His father Stephen J. Lord (1797–1851) played an important role in local church affairs as clerk of the Ecclesiastical Society, and Robert had been baptized together with his brother John in 1836. He was a schoolboy of nine when Rev. Davis Brainerd (1812–1875), Lyme’s recently arrived minister, pronounced in 1842 the excommunication of Mrs. Mary Outel, her name perhaps a variant of O’Toole. Church meeting records detail the case against her. After pledging “to walk with this church in a due observance of all its orders,” she had “connected herself with the Roman Catholics,” whom Rev. Brainerd denounced as “so degenerate and corrupt as to be unworthy of the name of a Christian Church.” Repeated efforts “to reclaim her” had been in vain, and she had maintained a “solemn determination to adhere to doctrines” deemed by Lyme’s church members “unscriptural and heretical and dangerous to the soul.”[2] Mrs. Outel, about whom no other information has been discovered, had likely connected with other Catholics in nearby New London, where the first Mass was celebrated in 1840.[3]

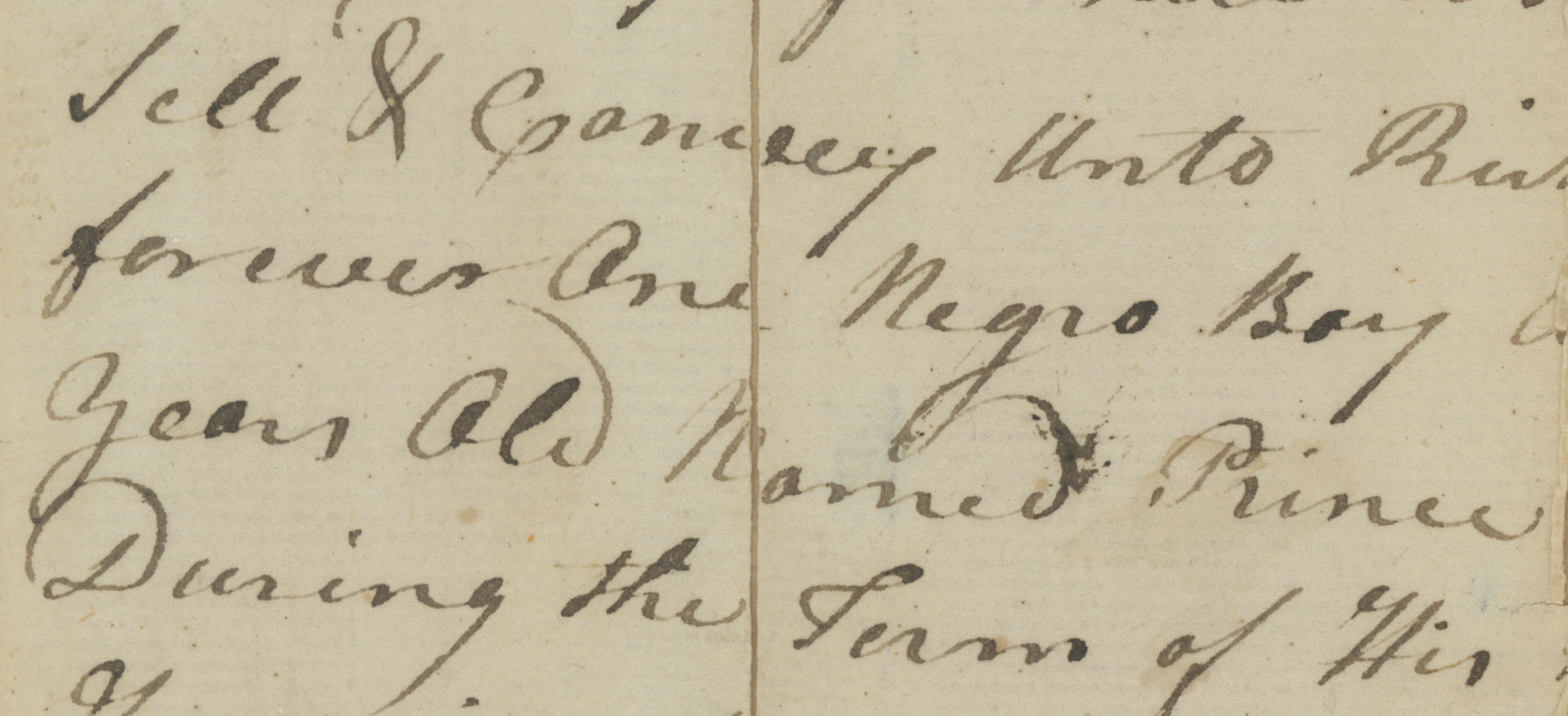

Despite the minister’s denunciations of Catholicism, Lyme’s prominent families relied on immigrants from Ireland to provide agricultural and domestic labor after the decline of northern slavery. Slave-owning in the town dated back at least to 1670, when “ye Negro servant Moses” was summoned to a court hearing with his owner Richard Ely (1610–1684), but the last ten enslaved persons noted in the census in 1810 had been freed before 1820.[4]By the time Connecticut finally abolished slavery in 1848, the town’s renowned packet ship captains, employed by prospering New York shipping lines, were facilitating access to foreign-born servants.

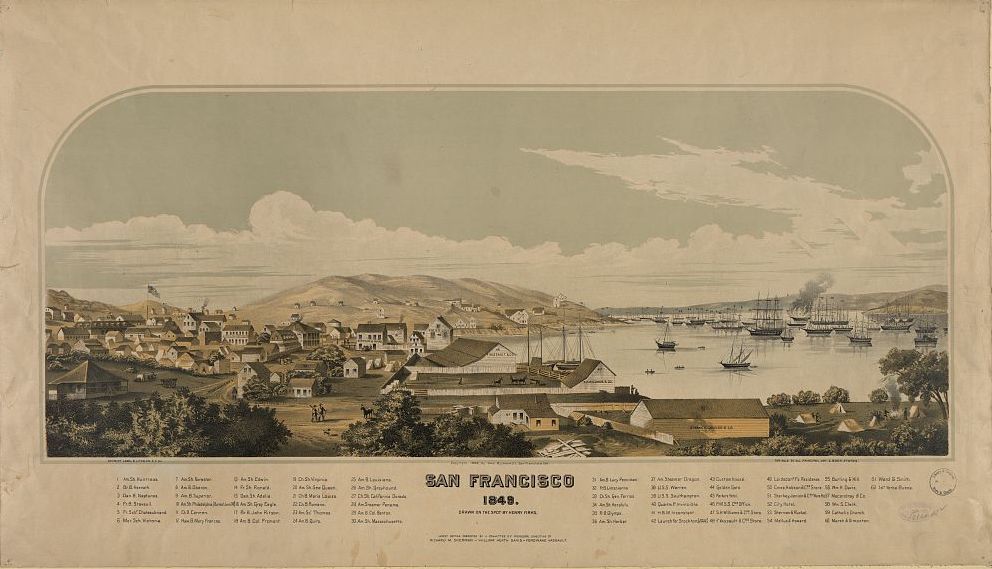

Samuel Walters, The Northumberland, 1847. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. William E. S. Griswold, Jr.

“Dr. [Shubael] Bartlett (1811–1849) wished me to ask you if you could get them a Boy in London, about twelve or fourteen years old, who had no friends to make trouble about him,” Helen Griswold (1820–1899) wrote from Lyme to her husband Captain Robert H. Griswold (1806–1882) before his return voyage from London in autumn 1845 on the packet ship Northumberland. “They would be delighted if you could as they have such dreadful work with their help.”[5] A request for a servant to assist the Comstock family in 1853 specified the need for a Protestant. The letter to W. B. Redfield in Lyme explained: “We learn, from Mr. Champion that you have facilities for furnishing servants. We want a good girl to do general work–one who understands cooking and washing & ironing. She must, if possible, be a protestant. We have no Catholic Church and consequently have heretofore been unable to retain a catholic for any length of time. If you can send us a first-rate girl, we shall be willing to pay good wages–say $5.00, or $6.00 a month.”[6]

Unidentified artist, Helen Powers Griswold. Private Collection

At least one Lyme family offered higher wages for domestic labor, as Mrs. Griswold wrote to her husband in June 1847. Mary Thomas, a neighbor of his family in Black Hall, was paying eight dollars a month to the woman caring for her infant, which prompted other servants to request a pay raise. “All the girls are making up their minds to strike for higher wages,” Mrs. Griswold reported. She added that his brother Matthew “was here in a dreadful way about it” and “blames Mary for giving so much, which I think is absurd for if Mr. Thomas is willing to give it I do not see what business it is of theirs.”[7]

Wage disparities, anti-Catholic views, and the lack of a place to worship were not the only difficulties that immigrants in Lyme faced during Robert Lord’s childhood. Three years before he wrote his Yale essay, two Irish maids died in the stately home, later known as “Boxwood,” that Richard S. Griswold (1809–1849), a partner in his father’s New York shipping firm, had built in 1840 near the Lord residence. “A dreadful circumstance occurred a few nights since,” Helen Griswold wrote in January 1847. “Two of Richard Griswold’s servants, (both Irish girls) took charcoal up into their room when going to bed, there was no fireplace in the room and in the morning were both found dead, it created a great sensation, and made Richard G. almost sick, he says he cannot get over it, although there was not the slightest blame to be attached to any one,–I could not sleep nights for thinking of it.”[8]

The Richard S. Griswold house, ca. 1885, had passed to his son Richard S. Griswold, Jr. Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

Although Robert Lord declared in his Yale essay that immigrant servants in coastal towns would not “settle down” and acquire an “urbane elegance of manners,” Ernestina Fisher (1842–1919), born in Prussia, defied that expectation. She arrived at the port of New York with her parents and eight siblings in 1854, then found work the next year, at age 13, in the home of William Ely Coult (1797–1877), a deacon in Lyme’s Congregational Church. Her own family’s religious affiliation is not known, but in December 1863, having reached the marriageable age of 21, she joined the town’s established church and married her employer, then age 65. Following his death, she inherited his 300-acre estate and sufficient means to pay tuition fees for private schooling for their three children. Mrs. Coult provided dancing lessons for her daughters, socialized with prominent church women, and contributed to the local women’s charitable Neck Road Society. Her obituary in 1919 praised her “lifelong habits of usefulness, charity, and honor.”

Mrs. Henry Noyes, Miss Coult, Mrs. Coult (right), clam bake, 1898. LHSA at the Florence Griswold Museum

Calling card, Mrs. E. F. Coult. LHSA at the Florence Griswold Museum

The impressionist painters who gathered at Florence Griswold’s boarding house after 1900 saw bucolic Old Lyme as a refuge from immigration and industrialization. Even though one of the town’s rapidly developing beach communities welcomed immigrants and their families, and a seasonal chapel in 1906 provided a place of worship for Catholic visitors from Connecticut’s cities, disparaging views of immigrants persisted. Other local beach developments restricted the sale of land with deeds that excluded “colored people” along with “Hebrews, Greeks, Italians, or Poles.”[9] When a new railroad track was laid in 1899, the local Sound Breeze newspaper had noted that “the gangs of Italians, the foremen, the stone men, the work trains, the surveyors, all make up a sight seldom seen hereabout.”[10]

South Asian immigrants were similarly unfamiliar and unexpected in Old Lyme in 2018 when “the merits and demerits of our foreign immigration” once again roused a heated national debate. Matthew Leifheit’s photographs document the support, encouragement, and affection that sustained Malik Naveed bin Rehman and his family after they found sanctuary in the town’s historic meetinghouse.

Matthew Leifheit, Malik Naveed bin Rehman, Zahida Altaf, and Roniya on Church Stairs, 2018. Archival pigment print. Courtesy of the artist

Special thanks to Charlie Beal for expert research assistance.

[1]Robert McCurdy Lord, “Is Foreign Immigration Beneficial to our Country?” Lord Papers, Box 8a. LHSA.

[2]First Church Records, p. 117 (October 29, 1842). First Congregational Church of Old Lyme Archives. Also see Carolyn Wakeman, Forgotten Voices: The Hidden History of a New England Meetinghouse (Middletown, 2019), p. 144.

[3]H. Hamilton Hurd, History of New London County, Connecticut (Philadelphia, 1882), p. 205.

[4]Wakeman, Forgotten Voices, pp. 6, 132.

[5]Helen Griswold to Captain Robert H. Griswold (September 16, 1845). Griswold Family Letters, LHSA.

[6]I. J. Comstock to W. B. Redfield (July 26, 1853). McCurdy Papers, Old Lyme Historical Society Archives.

[7]Helen Griswold to Captain Robert H. Griswold (June 12, 1847). Griswold Family Papers, LHSA.

[8]Helen Griswold to Captain Robert H. Griswold (January 24, 1847). Griswold Family Papers, LHSA.

[9]Carolyn Wakeman, The Charm of the Place: Old Lyme in the 1920s (Old Lyme, 2010), pp. 12-13; Jim Lampos & Michaelle Pearson, Rum Runners, Governors, Beachcombers & Socialists: Views of the Beaches in Old Lyme (Old Lyme, 2010), pp. 26, 53.

[10]The Sound Breeze (October 22, 1889).