Documents, Exhibition Notes

Exhibition Note: Fresh Fields–New Light on Familiar Settings

ON August 11, 2020

by Carolyn Wakeman

Feature Image: Frank Vincent DuMond, Top of the Hill, ca. 1906. Oil on academy board. Florence Griswold Museum, 1980.1

When the Florence Griswold Museum opened its doors on July 1, 2020, after closing during the coronavirus pandemic, a dazzling array of impressionist landscape paintings from the permanent collection filled its galleries. Accompanying labels placed familiar depictions of fields, riverbanks, and gardens in unaccustomed contexts. Fresh Fields: American Impressionist Landscapes from the Florence Griswold Museum invites visitors to marvel anew at the interplay of light and color infusing the painted landscape while also exploring the history and ecology of Old Lyme’s scenic settings.

Drawn to a place seemingly impervious to time and change, prominent painters like Childe Hassam and Willard Metcalf who gathered at Florence Griswold’s boarding house a century ago celebrated the town’s historic charm and its landscape of edges “just waiting to be painted.” Captivated by the setting and delighting in the company of fellow impressionists, the Lyme artists, most of whom visited seasonally, paid little attention to local events or local history. The startling contribution of Fresh Fields is its juxtaposition of an idealized rural past with the actual circumstances of the painted settings.

Mary Bradish Titcomb, Morning at Boxwood, ca. 1910. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, Purchase, 2019.30

Mary Bradish Titcomb, Morning at Boxwood, ca. 1910. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, Purchase, 2019.30

One highlight of the exhibition is Mary Bradish Titcomb’s elegant view of gracefully dressed young women, perhaps summer art students, reading and sewing in the intimate space of the Boxwood Inn’s vine-shaded front porch. Obscuring their faces, Titcomb creates an alluring portrait of gentility and seclusion, but she also shows one woman absorbed in a newspaper, mindful of events beyond the veranda. Traditional gender roles had not yet been challenged in Old Lyme in 1910, and another decade would pass before women gained the right to vote and claimed an expanding role in the public sphere. While most of the leading art colony painters’ wives opposed woman suffrage, a New York portrait artist named Katharine Ludington, raised in her family’s country estate a few doors from Boxwood, led the fight for voting rights in 1919. Connecticut ratified the 19th Amendment the following year.

Edmund Greacen, Bow Bridge, Old Lyme, Connecticut, ca. 1912. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, Purchase, 2006.14

Edmund Greacen, Bow Bridge, Old Lyme, Connecticut, ca. 1912. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, Purchase, 2006.14

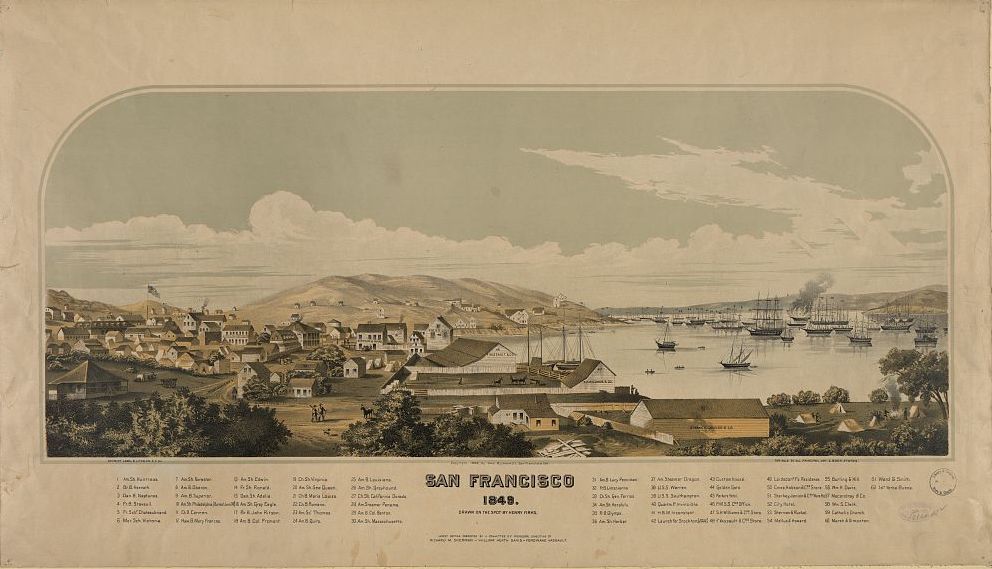

Edmund Greacen’s depiction of the sun-drenched landscape surrounding a century-old bridge near Florence Griswold’s estate also conveys a setting unchanged by modernization’s encroachments. The artist was likely unaware that the bridge over the upper Lieutenant River and the road that cut through woodland and meadows, significantly altering the landscape, were costly infrastructure improvements at a moment of economic expansion. Aspiring merchants like William Noyes, who built the stately home where Lyme colony artists resided, envisioned the growing town as a commercial hub for transport and trade. The new bridge in 1829 connected the stagecoach route from Boston with Higgins Wharf on the Connecticut River, where steamboats traveling between Hartford and New York picked up goods and passengers. Lyme’s ambitious plans dissolved less than a decade later in the financial crisis of 1837 that destroyed businesses and banks, prompting William Noyes to sell his estate to Florence Griswold’s father and purchase a mill near Albany.

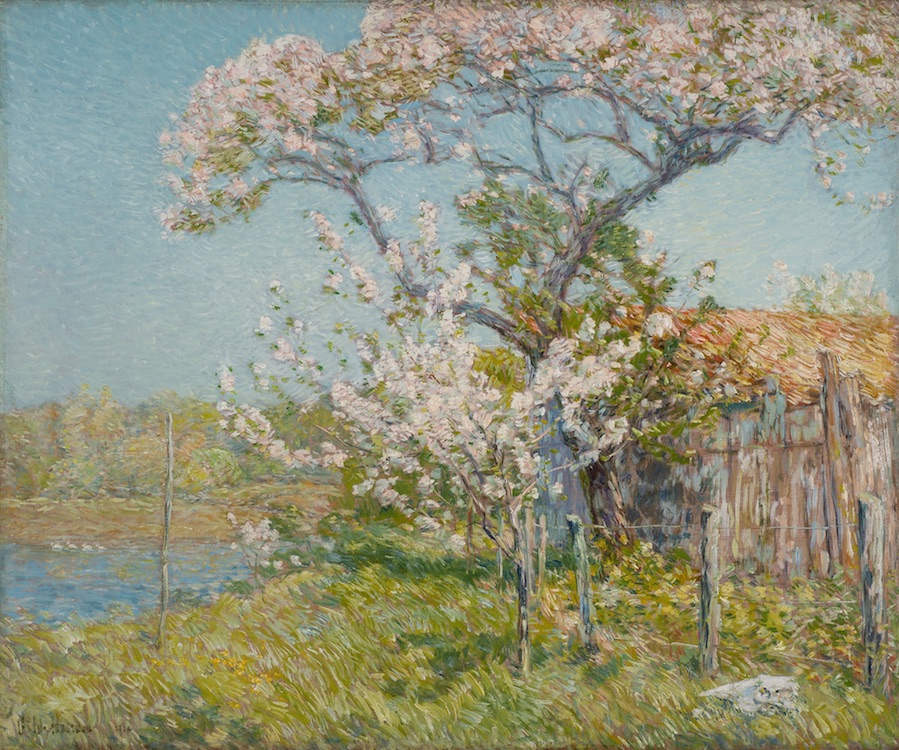

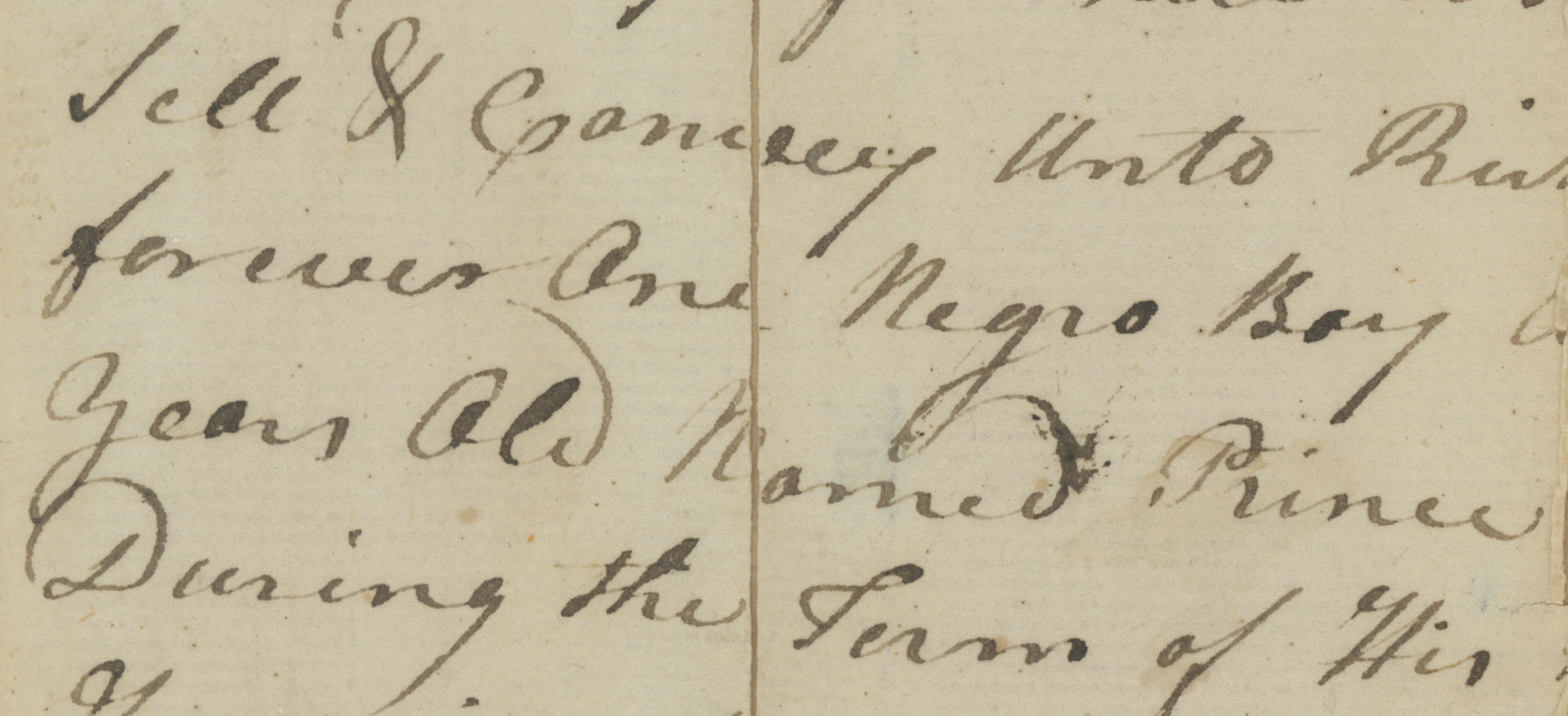

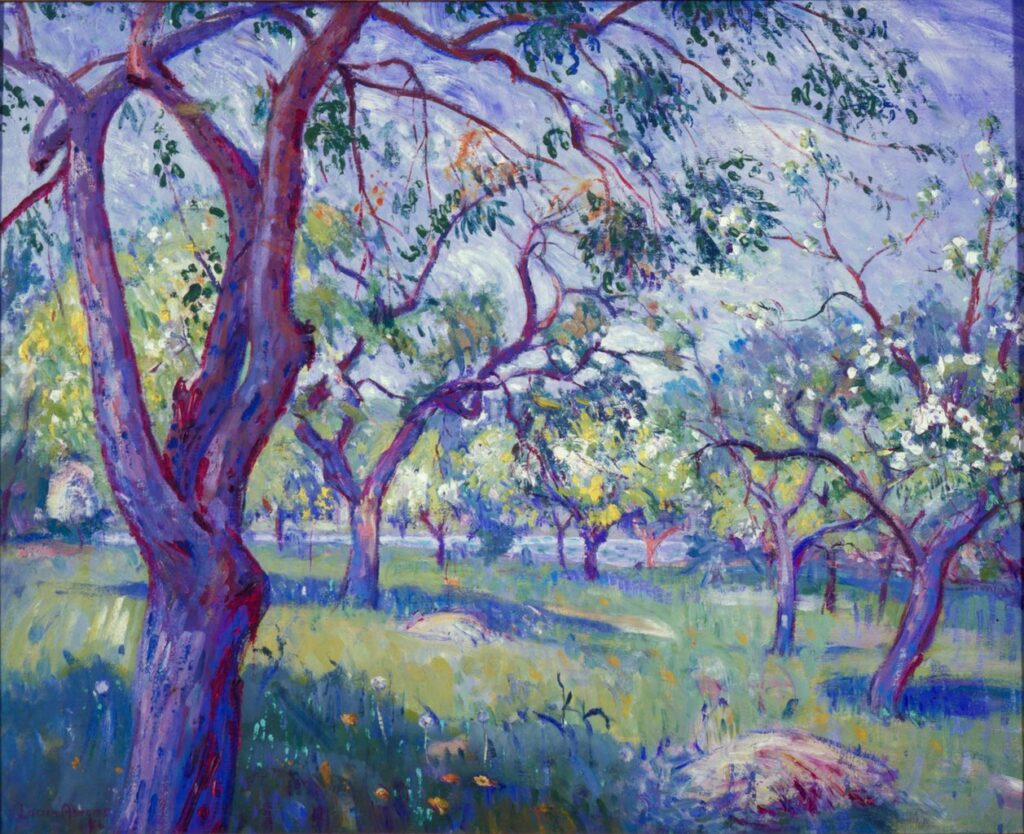

Lucien Abrams, The Orchard, 1916. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Mrs. Lucien Abrams, 1971.18

Lucien Abrams, The Orchard, 1916. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Mrs. Lucien Abrams, 1971.18

Lucien Abrams’s riveting depiction of aging apple trees behind the artists’ boardinghouse evokes a similarly forgotten past. Until 1820 “Negroes” held in bondage cultivated William Noyes’s estate and maintained his orchard alongside the Lieutenant River. That year he freed Samuel Freeman, the last of the enslaved workers who had labored for nearly a century on the property Miss Florence inherited. By the time Connecticut finally abolished slavery in 1848, Lyme families preferred white servants. Irish immigrants who had fled hardship and famine staffed her family’s home and tended its fields and gardens. Abrams’s painting of the blossoming orchard captures the gnarled trunks in brilliant color. It also recalls the lived history of those who planted, hoed, and harvested the Griswolds’ land.

The Fresh Fields exhibition prompts an awareness of the painted landscape at several points in time. Today the seclusion of the Boxwood porch is only a memory, and the elegant home with boxwood-bordered gardens constructed in 1840 by a New York shipping merchant sits behind the tall hedges of a condominium. The pastoral simplicity of the meadows surrounding Bow Bridge, built to spur commercial growth in the early 19th century, has been erased by an interstate highway and the sprawl of shopping centers. Six apple trees planted behind Florence Griswold’s house in 2006 today offer a vista point along the Robert F. Schumann Artists’ Trail. They recall not only the picturesque setting Abrams painted but also an agricultural landscape cultivated by enslaved and immigrant workers.

Fresh Fields holds successive moments in provocative tension. It celebrates the exceptional achievement of the artists who gathered in Old Lyme yet offers alternative perspectives through which to reflect on the landscape they painted. Settings removed from time and change in the artists’ nostalgic renderings acquire again the historical circumstances in which they also reside.

Childe Hassam, Apple Trees in Bloom, Old Lyme, 1904. Oil on wood. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of the Vincent Dowling Family Foundation in Honor of Director Emeritus Jeffrey Andersen, 2017.16