Exhibition Notes

Exhibition Note: Enduring Scenes from The Artist in the Connecticut Landscape

ON January 28, 2016

by Courtney Skipton Long, Curatorial Intern

Featured image (above): Robert Eshoo (b. 1926), Factory Scene, 1948. Watercolor on paper. New Britain Museum of American Art, Gift of the Artist, 2005.5

On a recent visit to The Artist in the Connecticut Landscape exhibition, on view in the Florence Griswold Museum’s Robert and Nancy Krieble Gallery through January 31, 2016, a guest asked whether the scenes represented in the gallery still survive today. This question has prompted a search for the views that inspired the artists’ images of Connecticut. The exhibition as a whole focuses on the history of American landscape painting through categorical arrangements of similarly themed paintings. Presenting images held in collections from around the State of Connecticut, the photographs, paintings, and drawings on display are grouped together to highlight shared subjects, such as, Landscape, Factory, Home, Farm, Water, Colonial, Road, Town, Countryside, Garden, and Forest. The seventy-nine images displayed in this exhibition also contribute to the online Connecticut History Illustrated database, comprising more than 10,000 digital images showing historic views of Connecticut.

Inspired by the visitor’s question, as well as the pairing of digital library and formal exhibition, this post is dedicated to pairing works of art from the exhibition with other historic and contemporary scenes found online that correspond to the pictorial themes of factories and landscapes.

Factory

Robert Eshoo’s Factory Scene captures New Britain’s dynamic, pond-front architectural landscape from 1948. In this watercolor, Eshoo highlights industrial elements associated with the American Hardware Corporation’s bustling center of production: train tracks, water tower, large air ventilators, and, what appears to be, the base of a large smokestack. These four architectural elements are all set within a landscape of brick and wood factory buildings represented using cubist techniques of denying mathematical perspective and three-dimensional modeling. Eshoo helps the viewer contemplate industry and production through the reduction of elements to simple geometric forms and planes of color.

#1311 with train 131 in March 1947 at Lockshop Pond and P&F Corbin Division. Note DEY-4 locomotive shoving hoppers up the coal trestle. Kent Cochrane. Thomas J. McNamara collection. http://www.newbritainstation.com/newbritain/west-of-station

When paired with the contemporaneous, 1947 black-and-white photograph of a train pulling away from Lockshop Pond and beside the American Hardware Corporation’s factory, one can begin to see just how much Eshoo manipulated the perspective of the buildings and vantage-point of the viewer. This photograph, attributed to Thomas J. McNamara, captures the ephemeral nature of billowing and trailing smoke from the in-motion train, which, in turn, blurs and manipulates the view of the industrial scene. Two features stand out, however, that are shared with Eshoo’s Factory Scene: the water tower and portion of the central smokestack.

Together, these two representations highlight different pictorial aspects of New Britain’s center for hardware production in the late 1940s, a landscape that can still be viewed today. The photograph offers, in documentary precision, an industrial scene in motion, as suggested by the train and trail of billowing smoke. Similarly, Eshoo’s watercolor suggests an active environment through the patterning of forms, acute building angles, and compact cluster of architectural elements. Images such as these reflect the kind of thematic grouping and varying presentation of Connecticut scenes that one will find while visiting The Artist in the Connecticut Landscape.

Landscape

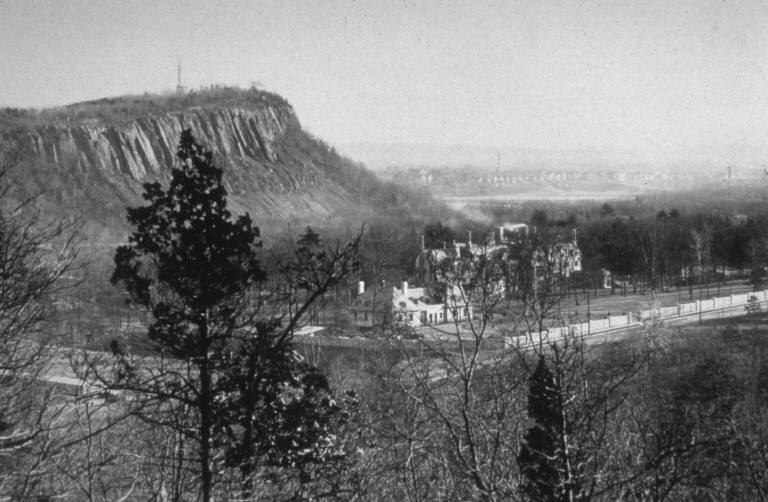

John Ferguson Weir (1841–1926), East Rock, New Haven, ca. 1901. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. 2002.1.160

When John Ferguson Weir became the first director for the Yale School of Fine Arts in 1869 he was just twenty-eight years old. Weir had moved to New Haven after building a successful painting career in New York. His association with a number of New York studios and art clubs, such as the Studio Building on West 10th Street, enabled him to exhibit his work to a wide audience. After settling at Yale, Weir dedicated his energy to building a professional art program that he hoped would rival the art institutions found in Europe.

Through his association with Yale, Weir became involved in local, New Haven-based art commissioning committees. One such committee was created to direct the design and placement of a Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, which was realized in 1887 and now stands prominently on top of the East Rock ridge overlooking downtown New Haven. Weir was supposedly unsatisfied with the selected obelisk design and final location of the monument and, therefore, removed himself from the committee. This supposed difference in ideas and aesthetics may indicate why Weir decidedly omitted the memorial in his 1901 painting East Rock, New Haven.

Weir’s representation of the trap rock cliffs and surrounding landscape showcases a glorious golden autumn scene set against the backdrop of one of Southern Connecticut’s most magnificent ridges formed some 200 million years ago. In his painting, Weir highlights an uninhabited landscape, as suggested by the dilapidated post and beam fencing, that seems to remind the viewer of their littleness in relation to the imposing and majestic presentation of East Rock in the background. This potential reading of Weir’s painting may also help us to re-think his exclusion of the Soldiers’ and Sailor’s Monument as a symbolic rejection of honoring Man over Nature.

East Rock and the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in New Haven, Connecticut, viewed from the roof of Sheffield-Sterling-Strathcona Hall at Yale University. Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/16/East_Rock_from_SSS_Hall,_October_17,_2008.jpg

The painting of East Rock, New Haven joins other representations of New Haven’s historic landscape. As we can see in the contemporary photograph above, East Rock continues to be a picturesque scene for many artists and nature-lovers. Even as early as 1900, Yale began a photographic repository, which features many landscape scenes from around New Haven and Yale’s Campus. The photographs seen here from 1900 and 1964, below, highlight the growth in population density surrounding the East Rock cliffs and imbue Weir’s painting with a new kind of bucolic nostalgia for a landscape unchanged.

Above: East Rock. Repository Name: New Haven Colony Historical Society. Original Site: New Haven, East Rock. Photograph, c. 1900 (?). Source: http://images.library.yale.edu/nhsize3/YVRC/D4165/257776.jpg

Below: East Rock Connector. Repository Name: New Haven Historical Society. Original Site: New Haven, East Rock. Photograph, 1964. Source: http://images.library.yale.edu/nhsize3/YVRC/D9990/258056.jpg

Finally, East Rock, New Haven highlights Weir’s desire to capture the landscape from his local surroundings. In this way, Weir joins many other of Connecticut’s artists, such as Frederic Church and Charles deWolf Brownell, who sought out iconic “stories in stone,” including West Rock in New Haven, or Joshua Rocks along the Connecticut River near Old Lyme. Together, representations like Eshoo’s Factory Scene and Weir’s East Rock, New Haven joined with so many other landscape scenes on loan to the Florence Griswold Museum from around Connecticut prompts us to consider both how the artists looked at their local scenery and whether those vistas survive today.