by Carolyn Wakeman

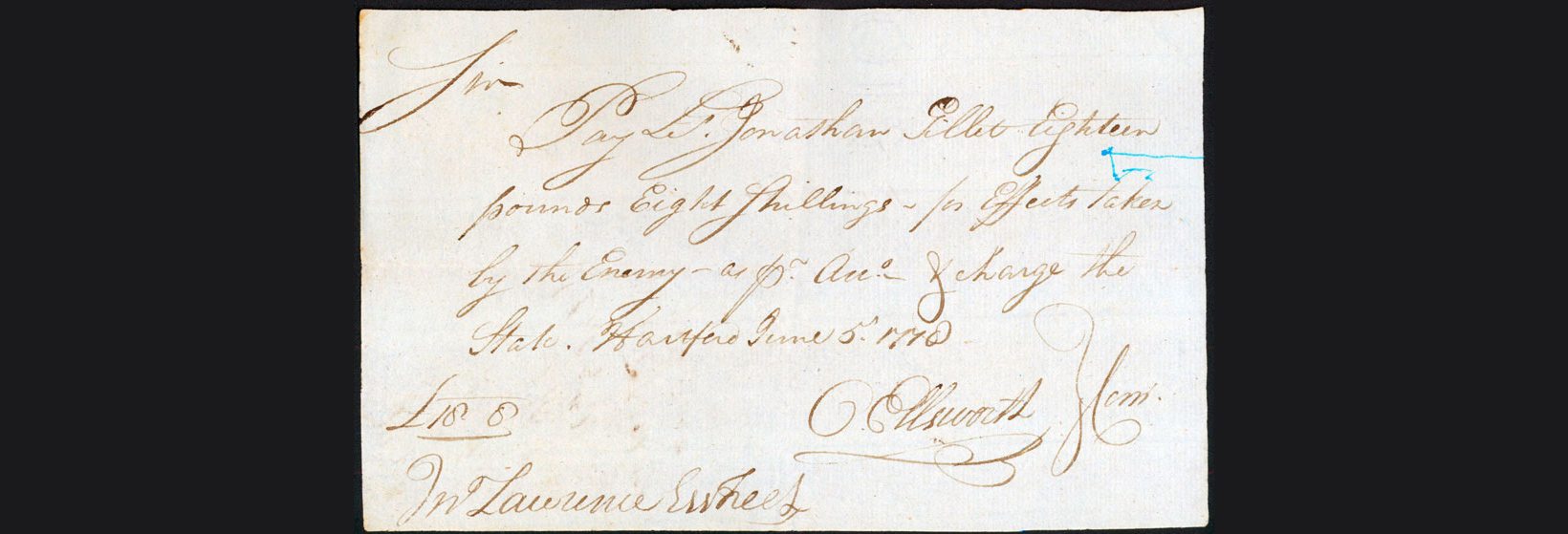

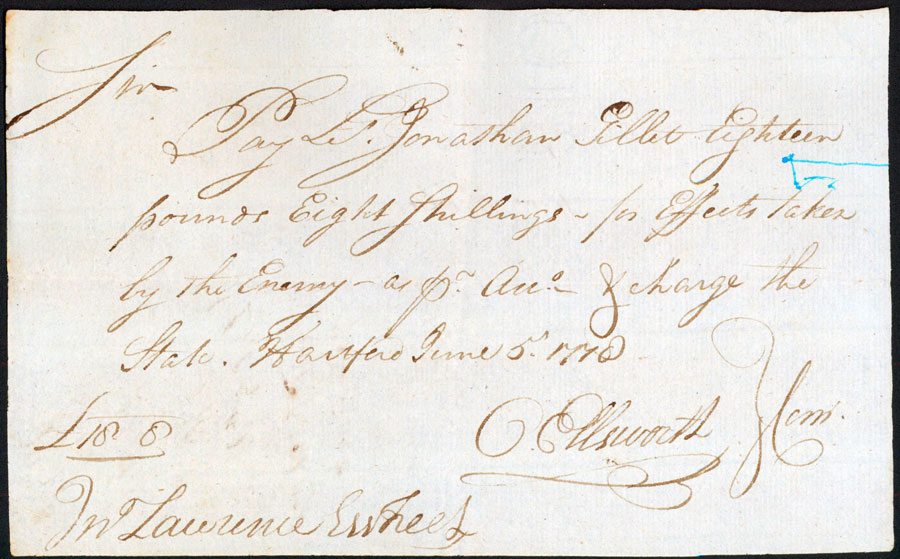

Featured Photo (above): Authorization to pay Lt. Jonathan Gillet, 1778. LHSA

In 2013 the noted silver designer Siro Toffolon donated to the Florence Griswold Museum an important collection of Revolutionary War papers relating to Capt. Jonathan Gillet of Lyme. During the course of researching and cataloguing this collection, trustee and editor Carolyn Wakeman made a fascinating discovery that is told in this posting to From the Archives.

Most of the items in Capt. Jonathan Gillet’s collected papers made sense. Deciphered and pieced together, they traced the life of a prominent farmer, storekeeper, and militia officer who trained Lyme’s foot soldiers as the War of Independence neared. But the most intriguing document, an order to pay Lt. Jonathan Gillet “for Effects taken by the Enemy,” just didn’t fit.

Family Matters

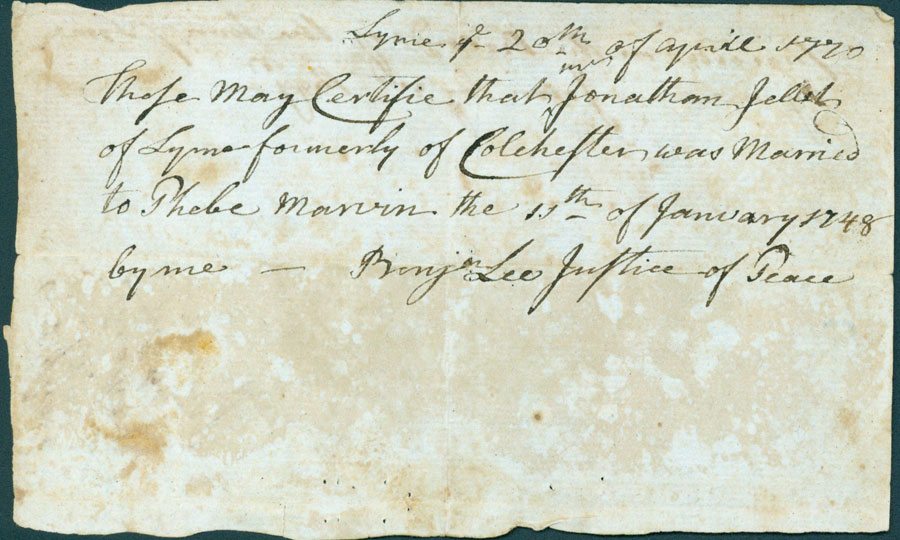

The Gillet papers bring vividly to life a Lyme family and farm on the eve of the Revolutionary War. The earliest item is a deed recording Jonathan Gillet’s purchase in 1742 of part of a farm with a house and barn in Colchester.[1] Already propertied at age 22, he made a suitable match six years later for 21-year old Phoebe Marvin (1727-1776), whose father owned large tracts of land in Lyme. A slip of paper signed by Lyme’s Justice of the Peace certified their marriage for the town records.

Certification of Mr. Jonathan Gillet’s marriage to Phoebe Marvin in 1748. LHSA

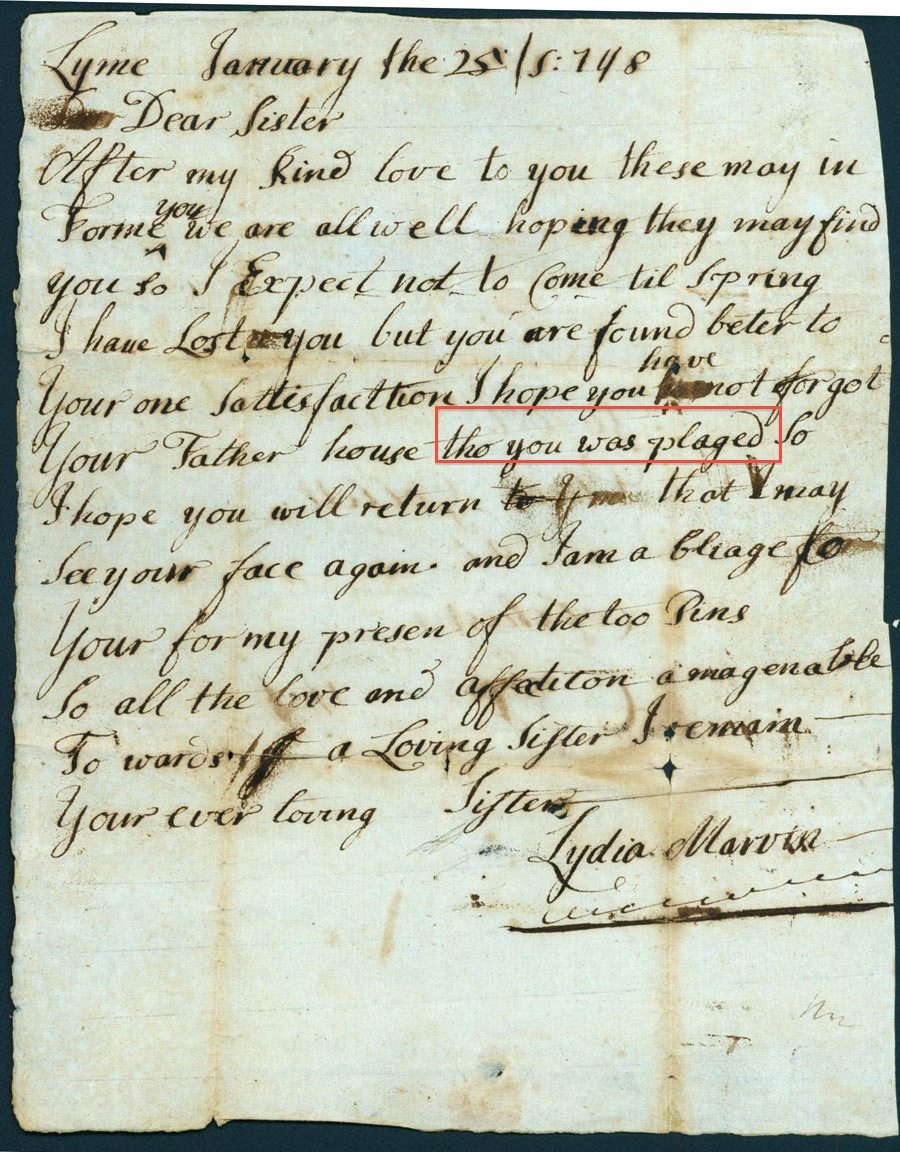

Phoebe’s departure for Colchester brought a poignant letter from her sister Lydia, age 15: “I have Lost you,” she wrote with improvised spelling, “but you are found beter to Your one Sattisfaction I hope you have not forgot Your Father house tho you was plaged So I hope you will return so that I may See your face again.” In closing Lydia sent “all the love and affectiton amagenable To wards a Loving Sister.” Why Phoebe was “plaged” at home is not revealed, but their father’s remarriage in 1746 to a widow from Colchester may have caused strains in the household.

Lydia Marvin to Phoebe Gillet, 1749. LHSA

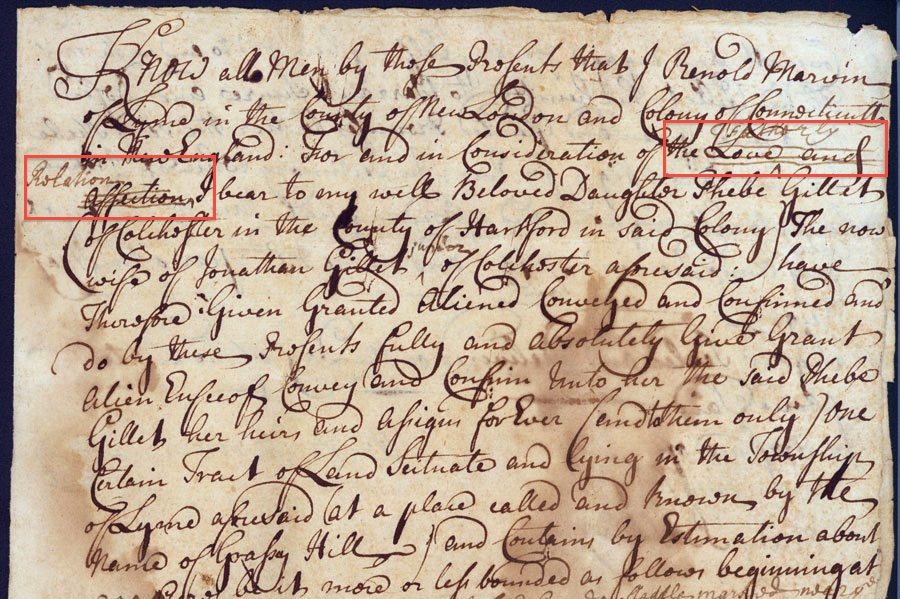

A substantial gift of land drew Phoebe back to Lyme with her husband and first child a year later. In 1749 Renold Marvin (1669-1761) gave his “well beloved daughter” 350 acres of pasturage and woodland on Grassy Hill above today’s Rogers Lake, then called Marvin’s Pond. Curiously the deed shows the conventional words “for love and affection” scratched out and replaced by the more transactional phrase “for fatherly relations.” But whatever difficulties lingered in the family, the Gillet farm prospered. By 1769 Phoebe, age 42, had given birth to a daughter and ten sons.

Phoebe Marvin’s deed from her father, 1749. LHSA

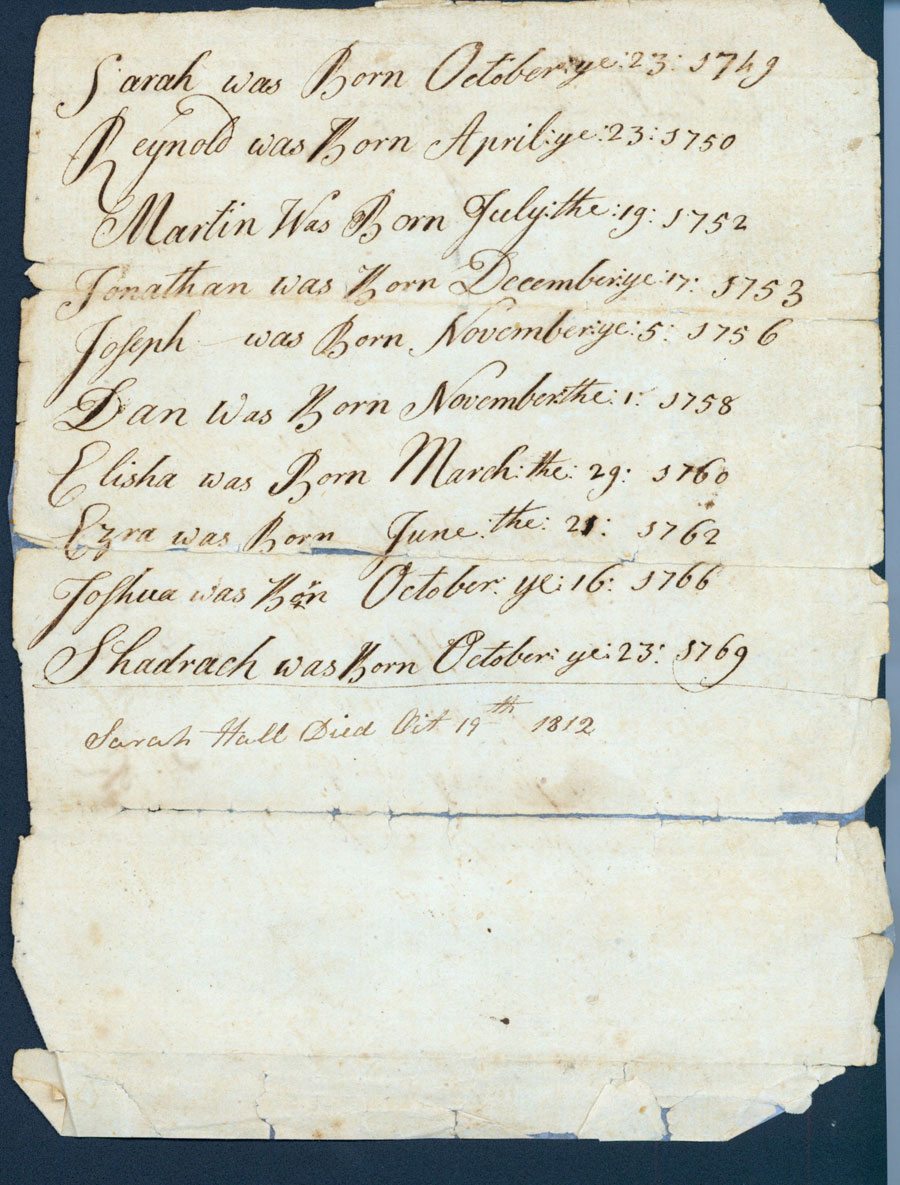

Births of Lt. Gillet’s children, recorded in the records of the Town of Lyme, LHSA

Grassy Hill Farm

The expanding coastal trade brought commercial opportunities to Lyme, and in 1752 Elisha Sheldon (1709-1779) and other enterprising merchants urged the widening of the “Great Bridge” over Lieutenant’s River to allow the passage of ox-drawn carts. Wharves and warehouses multiplied, and new roads, including a “highway” over Grassy Hill in 1759, encouraged local initiatives.[2]

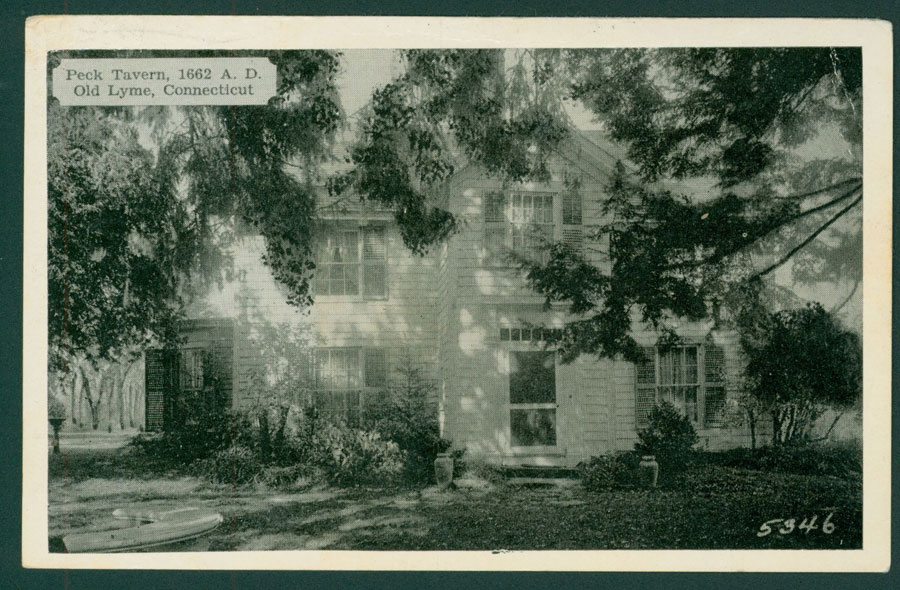

A deed recording Jonathan Gillet’s purchase from John Peck (1716-1785) of a stretch of meadow along the west bank of Lieutenant’s River in 1766 indicates his diversifying interests. Over the next decade he bought two more “pieces of Meaddow” just north of the Great Bridge that increased his supply of valuable salt hay and also provided access to imported goods. On the opposite bank stood the busy warehouses of the Scots-Irish merchant John McCurdy (1724-1785). When John Peck built a new house with a taproom on the post road through town in 1769, McCurdy established a store on the Peck Tavern premises.[3]

Peck’s Tavern, postcard. LHSA

Lower bridge across Lieutenant River in winter, ca. 1880. Courtesy of Werneth Noyes Collection

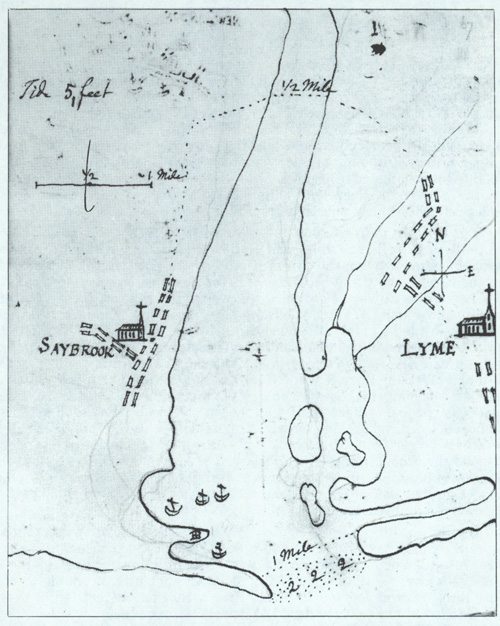

Ezra Stiles, Map of Lyme, showing site of Jonathan Gillet’s meadows, 1768. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

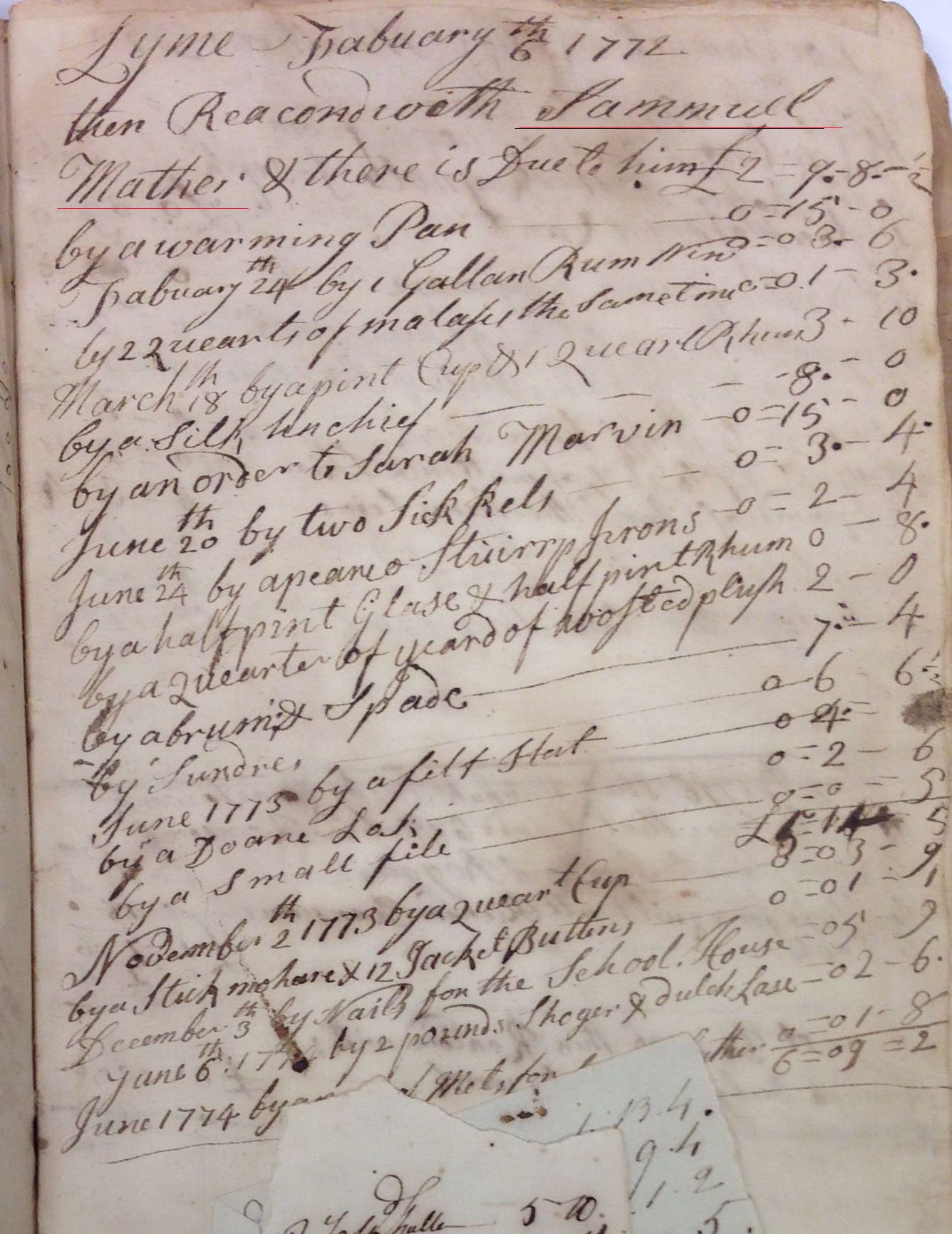

Already an officer in the local militia, Jonathan Gillet also contributed importantly to the growth of a mercantile culture in Lyme. Pursuing his own commercial prospects on Grassy Hill, he kept an indexed record book, starting in 1771, that noted charges for goods and services to more than sixty customers over fifteen years. The Congregational minister George Beckwith, the Separatist preacher Daniel Miner, and the physician Samuel Mather all had active accounts.

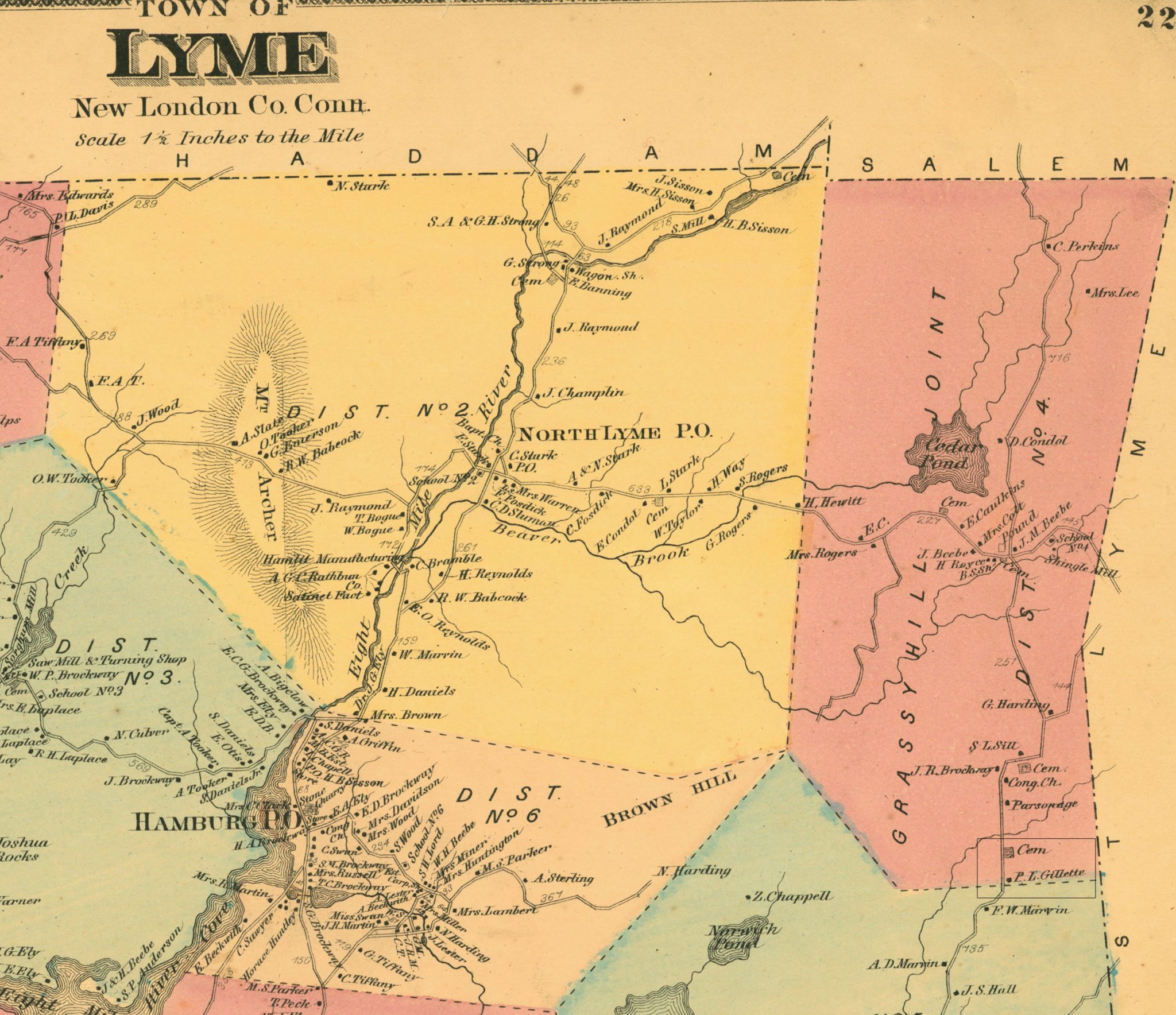

Map of Grassy Hill District, Town of Lyme, showing location of Gillet house, 1868. LHSA

The Grassy Hill farm sold mostly local products like beef and mutton, clover seed and oats, flax and wool, potatoes and turnips, candles and honey, cider and vinegar, cheese and butter, hens, “fat geese,” and a small calf. Charges also appear for imported merchandise items like indigo, tobacco, molasses, and rum; for sundries and tools like buttons, a warming pan, a small file, stirrup irons, sickles, and “nails for the School House”; for sawmill products like planks, shingles, and white oak barrel staves; and for farm work that ranged from plowing, mowing, raking hay, carting coal, and making walls, to killing hogs and a bull.

Jonathan Gillet’s record book, showing account of Samuel Mather, 1772. LHSA

The Gillet farm was a family venture. As his eldest sons Reynold, Martin, and Jonathan, Jr., grew, he hired out their labor for hoeing corn, raking hay, clearing land, and sawing staves. Sometime he did the heavy work himself. On July 23, 1771, at age 51, he entered three separate charges for a load of hay, complaining that he had to spend “two Days a gittin of it and I find my Self a gitten of it Carting of a Load of hay 3 yoak of oxen my Self Reynold Can’t.”

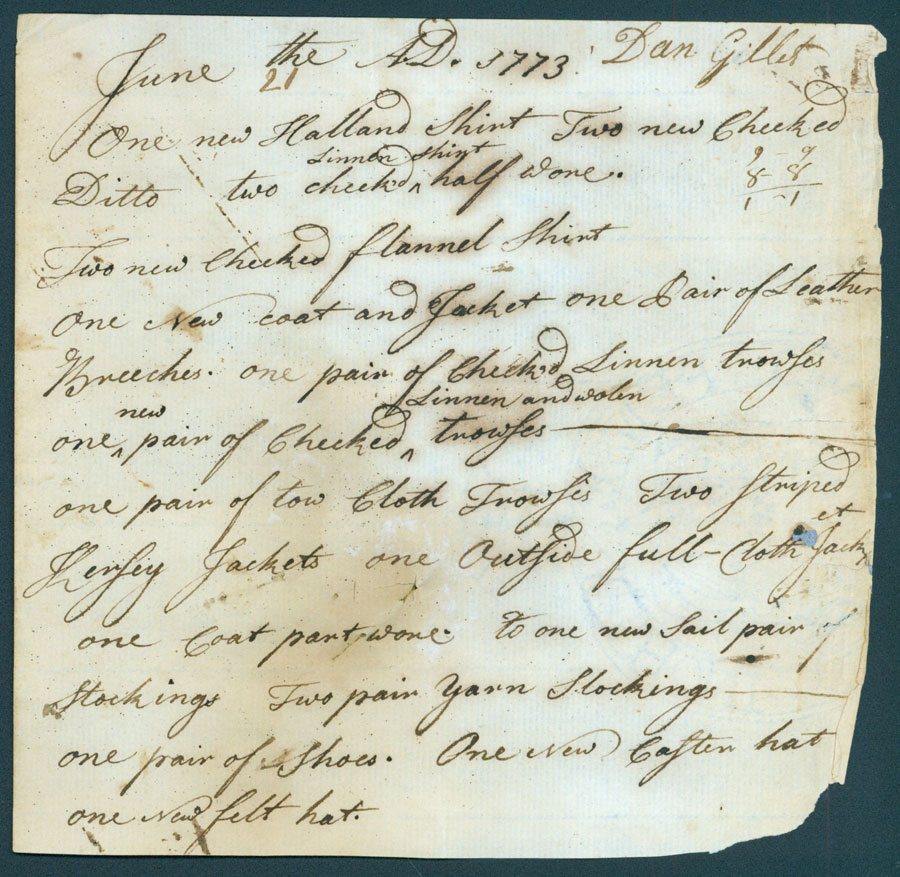

List of clothing, Dan Gillet, 1773. LHSA

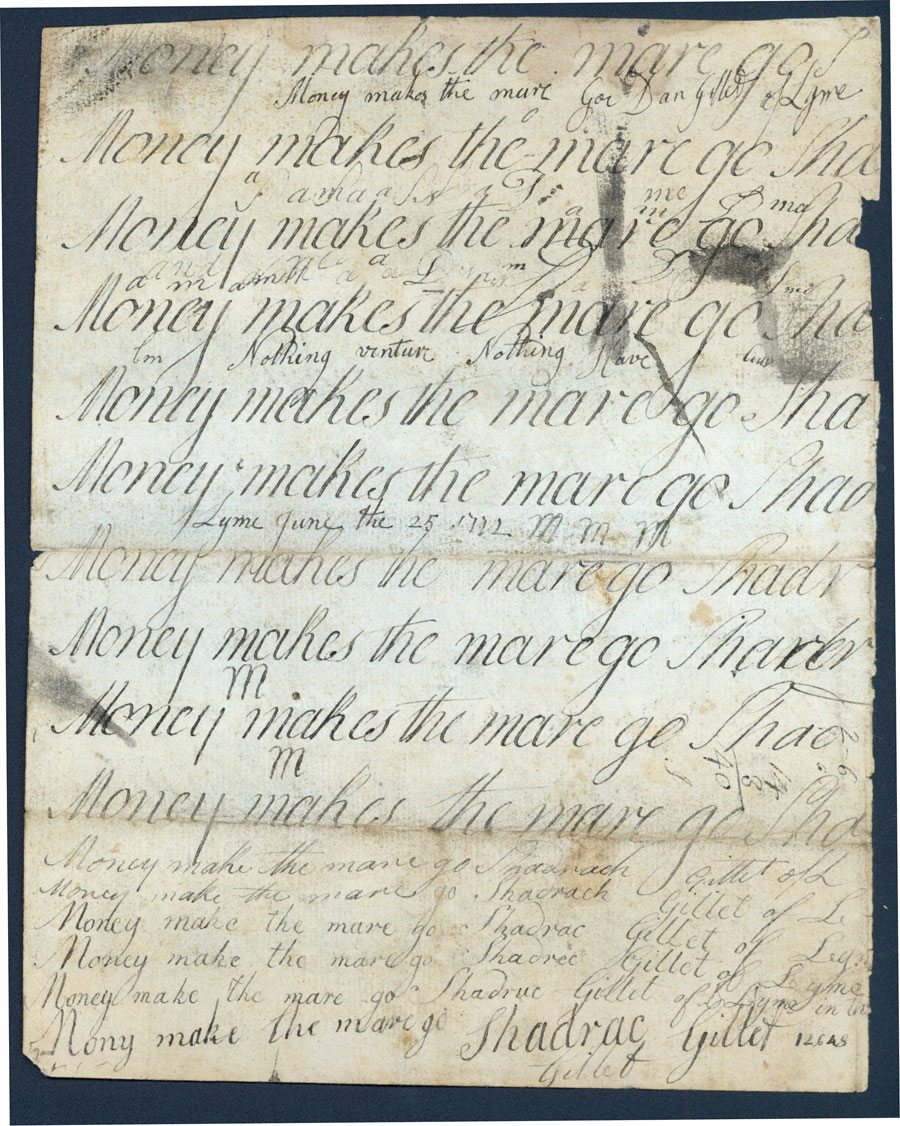

Gillet apparently made shoes and repaired boots, and his wife almost certainly wove flax into lengths of linen cloth. Phoebe may also have made the yarn stockings, linen and woolen trousers, and “two checked Linnen shirts half done” that Dan, the fifth son, listed on what appears to be an inventory of stocked clothing. Perhaps Dan himself learned tailoring. A page saved from his copybook reflects the 14-year old’s enterprising spirit. “Money makes the mare go” and “Nothing Venture Nothing Have,” he wrote in careful schoolboy script.

Copybook page, Dan Gillet, 1772. LHSA

Training Lyme’s Militia

Colonial opposition to British authority stiffened after Parliament approved the Stamp Act in March 1765, and Lyme’s leading citizens played an active role in the gathering resistance. The prospering merchant John McCurdy traveled to New York and brought back texts promoting the cause of liberty. The First Society’s minister Stephen Johnson (1724-1786) wrote inflammatory letters that appeared in The New-London Gazette warning that the Stamp Tax would bring enslavement to future generations.[4] As grievances mounted, patriotic sentiment flared.

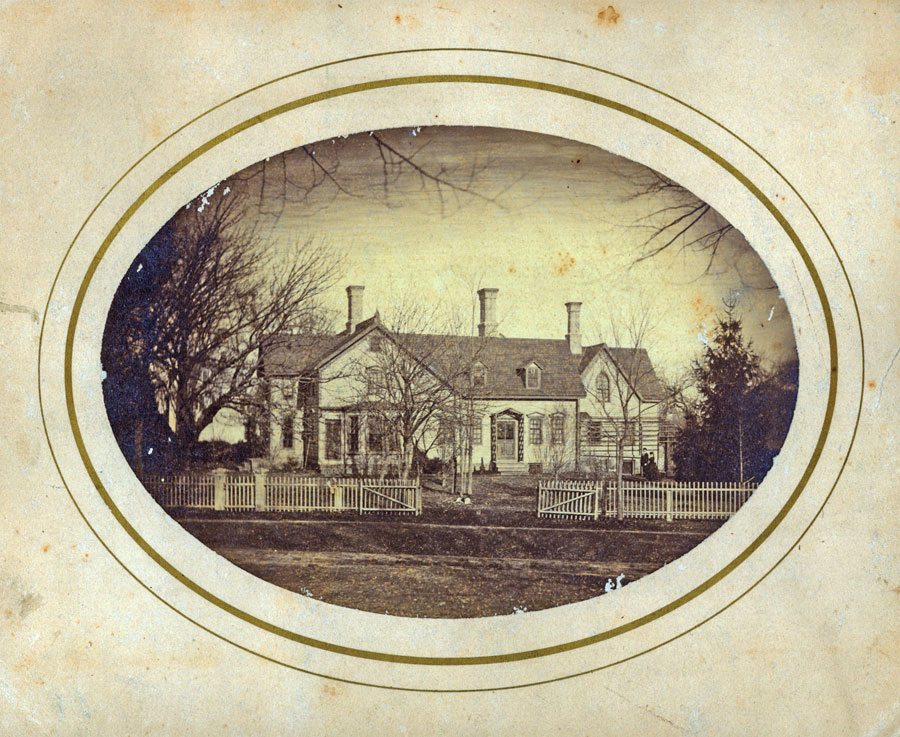

John McCurdy house facing town green, showing later additions, ca. 1890. LHSA

A mock trial for the stamp collector Jared Ingersoll (1749-1822) took place before the “good people of this colony” in August 1765, probably on the town green. A sardonic report in The New-London Gazette described the “Stamp-man” being summarily accused, sentenced, tied to a cart, drawn through the streets, whipped, and hanged in effigy from a 50-foot gallows. Then a “funeral Ceremony was performed by the Blacks in the Place, at which point there appeared a universal Satisfaction in the Countenances of all present.” Whether Jonathan Gillet witnessed the stamp collector’s fate cannot be known, but observers were said to be “very numerous.”[5]

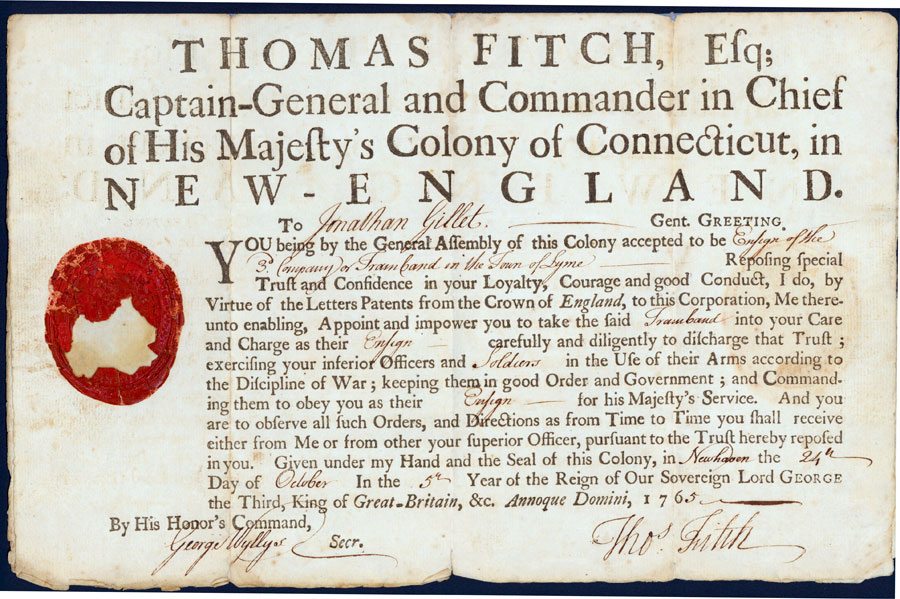

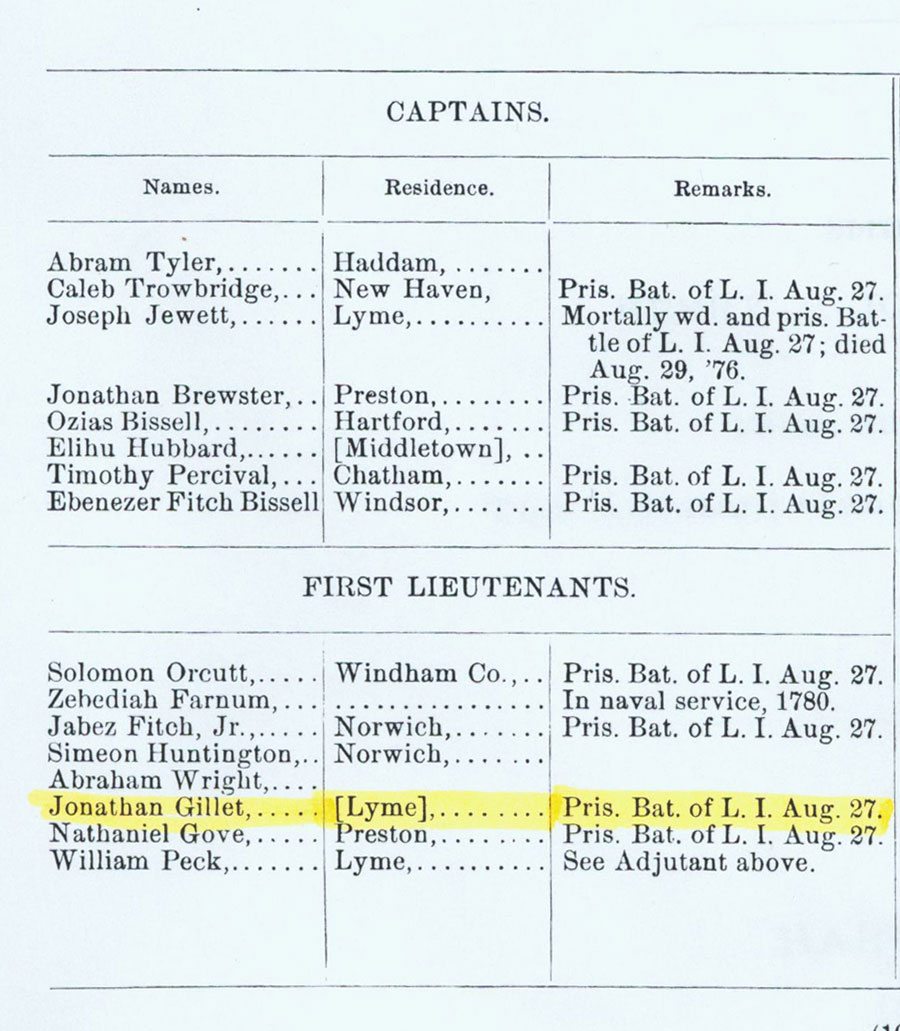

Jonathan Gillet, Commission as Ensign, 3rd Militia Company, 1765. LHSA

Two months later Gillet was commissioned Ensign of the town’s 3rd Militia Company, which enrolled local men, most of them farmers, from an area stretching across North Lyme between the Connecticut River and Grassy Hill. His promotion to Lieutenant in 1769 brought added responsibility.[6] Militia service was compulsory in the Connecticut colony, and Lyme’s foot soldiers drilled on legally mandated days.

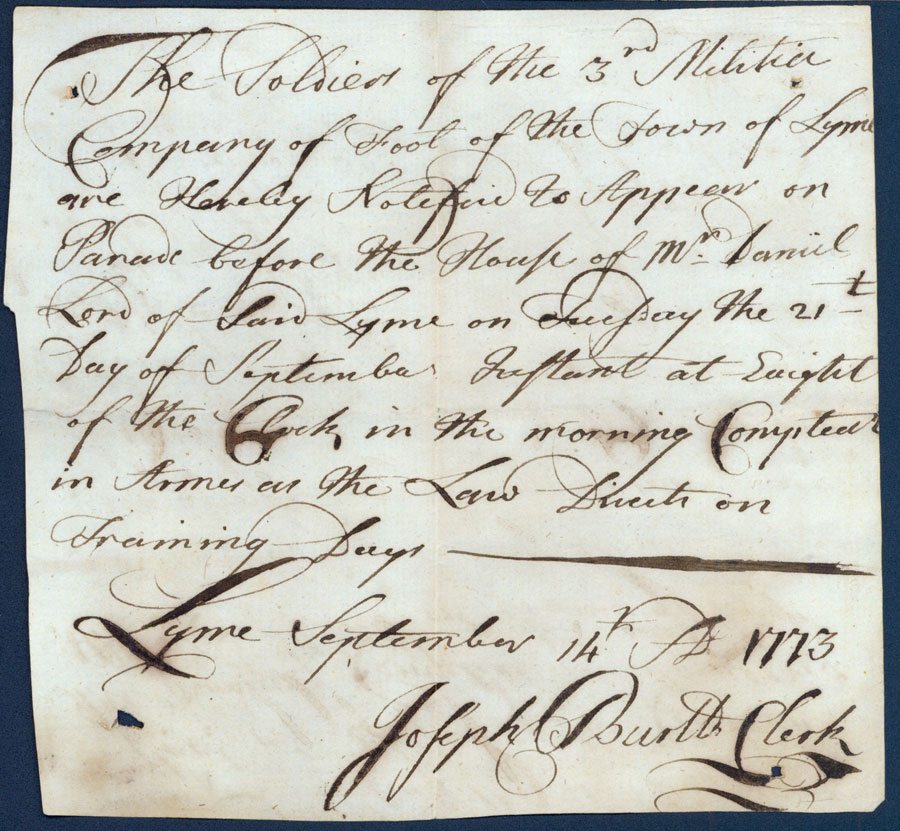

Notification of militia training day, 1773. LHSA

Lt. Gillet received written notification in 1773 for: “The Soldiers of the 3d Militia Company of Foot of the Town of Lyme. . .to appear on parade before the house of Mr. Daniel Lord of said Lyme on Tuesday the 21st day of September Instant at Eight of the clock in the morning compted in armes as the law directs on training days.” The field across from Daniel Lord’s house, today’s Ashlawn Farm, likely served as the parade ground.

Daniel Lord house, now Ashlawn Farm, showing field used as militia parade ground, ca. 1888. Courtesy Lyme Public Hall

Local officers like Lt. Gillet could well have been present in March 1774 when the “Sons of Liberty” confronted a peddler on horseback with a large bag of tea that was subject to British tax. According to an observer, the group “assembled in the Evening, kindled a Fire and committed the Bag with its contents to the Flames, where it was all consumed and the Ashes buried on the Spot.”[7] Six months after the “tea party,” rumors of a massacre in Boston reached Lyme. An urgent message announced “the necessity of rallying all your forces immediately.”[8]

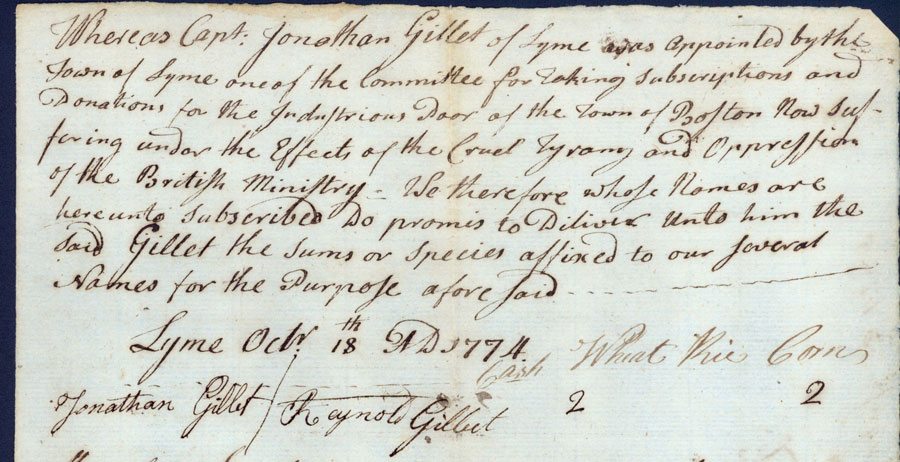

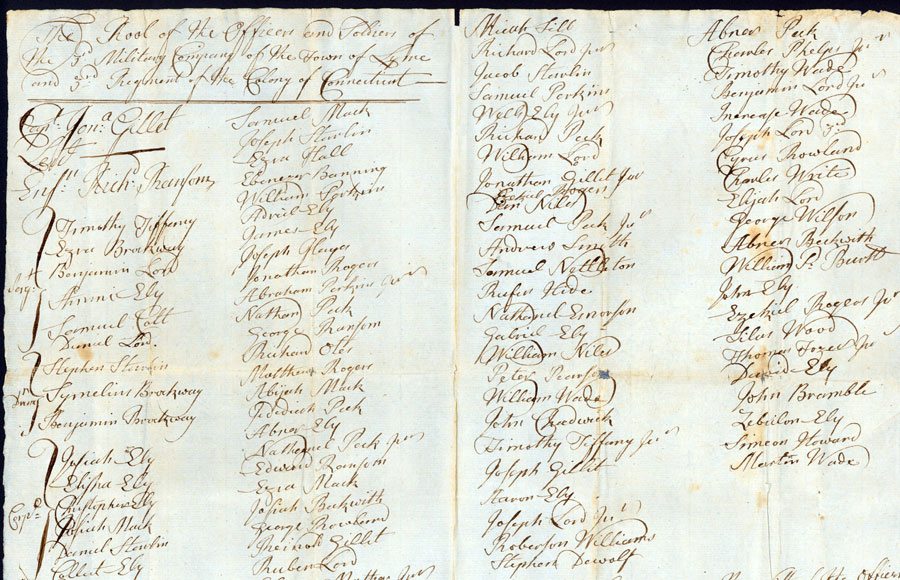

Within a week Capt. Jonathan Gillet, recently promoted, had been appointed to a committee charged with collecting relief funds for those oppressed by British tyranny in Boston.[9] Two of his sons and several neighbors promised to repay him in corn and wheat for pledged donations. As war drew closer, a double-page list, dated January 16, 1775, identified the officers and soldiers required to serve in the 3rd Militia Company. The names of his sons Reynold, Jonathan, Jr., and Joseph appear on the muster roll.

Promissory note to Capt. Gillet for donations to the Town of Boston, 1774. LHSA

Roll of Officers and Soldiers, 3rd Military Company, Town of Lyme, 1775. LHSA

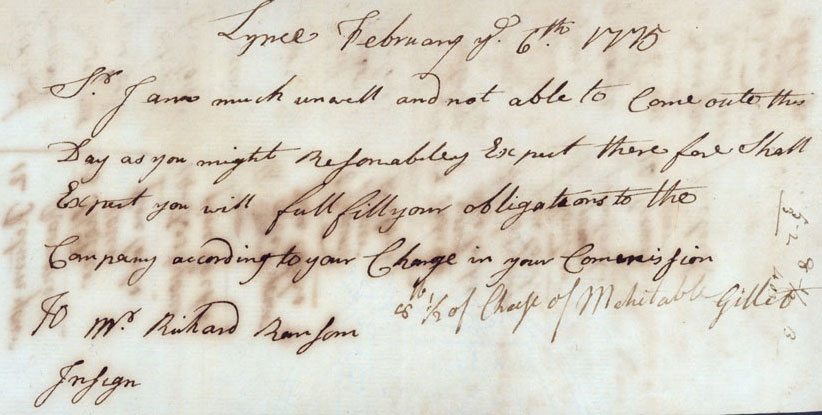

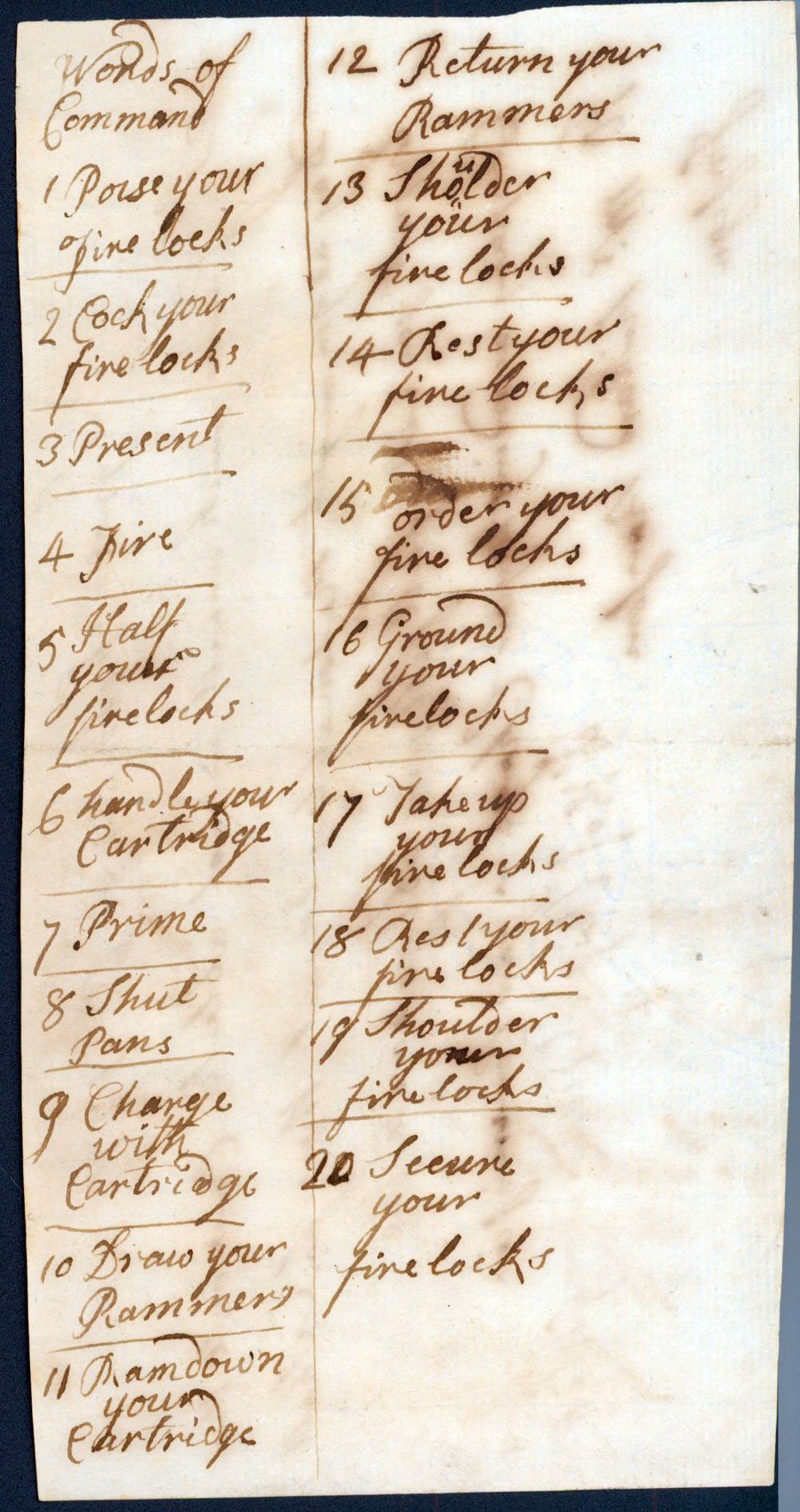

Feeling “much unwell” in February, Capt. Gillet sent a message instructing Ensign Richard Ransom to take responsibility for militia training. On the back of his note, he listed the necessary “Words of Command.” Events then unfolded rapidly. Express rider Israel Bissell (1752-1853) reached Lyme at one o’clock in the morning on April 21 with news of fighting in Lexington. Led by Capt. Joseph Jewett (1732-1776), more than sixty militiamen gathered later that day and marched to Boston in response to the Lexington Alarm.[10]

Capt. Jonathan Gillet, note to Ensign Richard Ransom, 1775. LHSA

Militia training commands, Lyme, 1775. LHSA

Revolutionary War recruitment poster, illustrating military commands. Connecticut Historical Society

Mistaken Identity

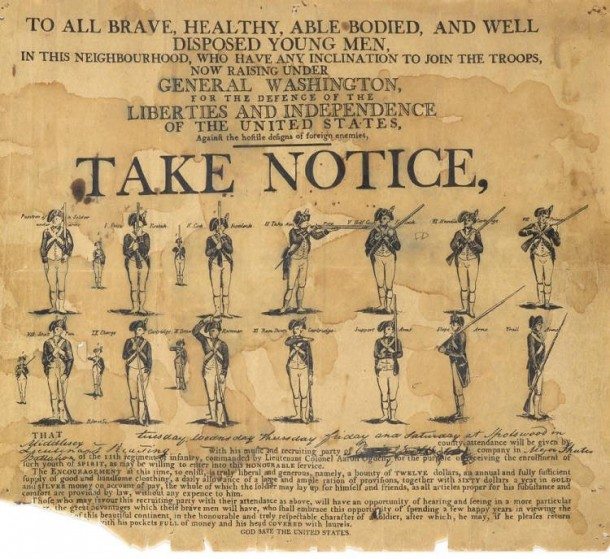

Connecticut regiments suffered heavy losses the following summer in fierce fighting on Long Island. Capt. Jewett was fatally stabbed on August 27, 1776, and Lt. Jonathan Gillet, who served in Col. Jedediah Huntington’s 17th Regiment, was captured that same day. Military records listed his residence, in brackets, as Lyme.[11]

Miltary records, 17th Continental Regiment, showing Lt. Jonathan Gillet [Lyme] taken prisoner, Battle of Long Island, August 27, 1776. LHSA

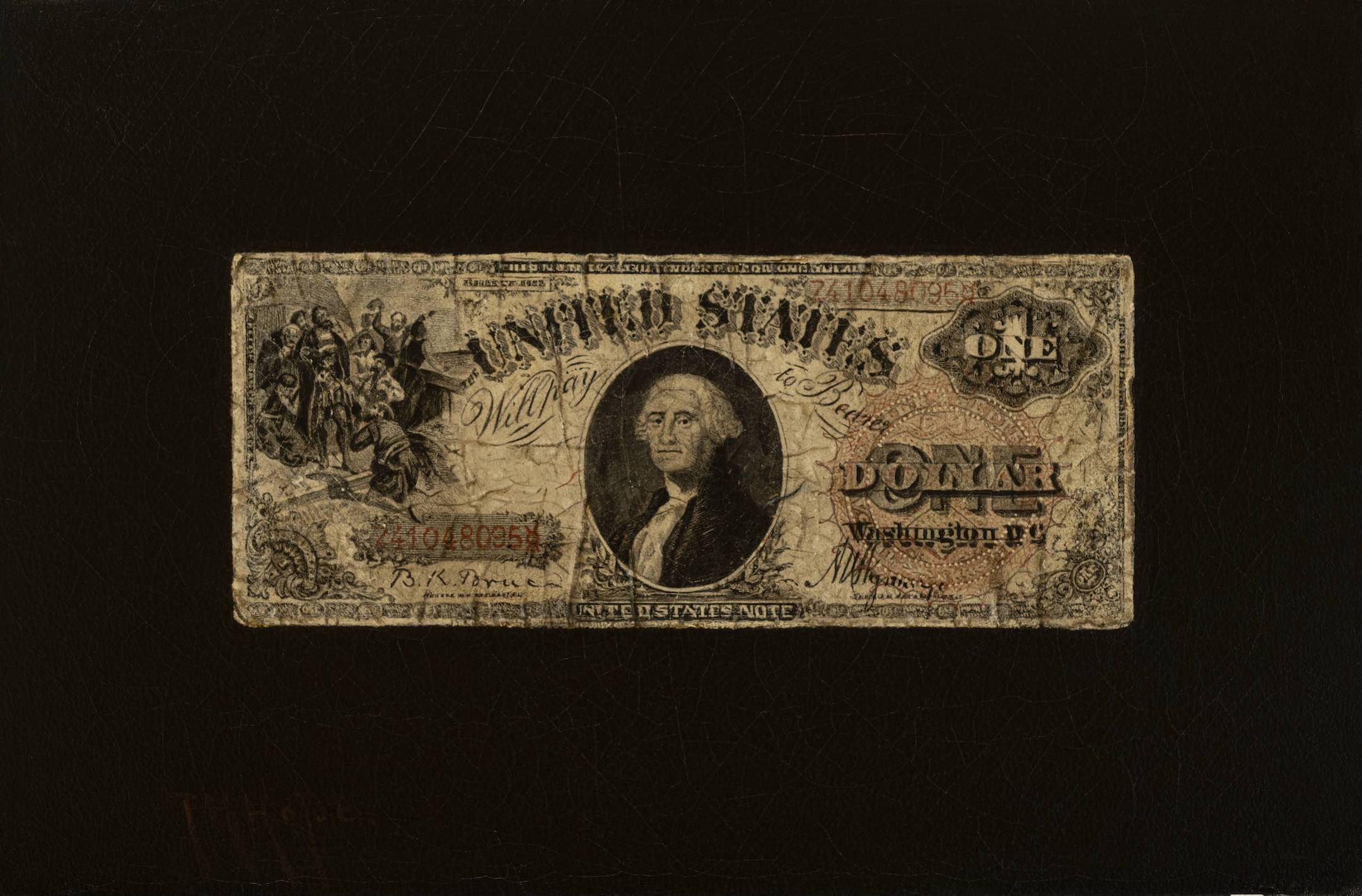

In a letter to his wife, Lt. Gillet described harsh conditions in a British prison. Exchanged in 1778 in extreme ill health, he died the following winter.[12] The note that Oliver Ellsworth (1745-1807) wrote in Hartford on June 5, 1778, authorizing payment to Lt. Gillet “for Effects taken by the Enemy” and signed “Jona Gillet,” remains safely preserved in the Gillet Collection in Lyme. But it raises puzzling questions.

Authorization to pay Lt. Jonathan Gillet, 1778. LHSA

The reimbursement order included with Capt. Gillet’s deeds, receipts, and militia notices suggests that he, or perhaps his son Jonathan, was captured on Long Island. A veteran’s burial marker placed in Lyme’s Laysville Cemetery with the inscription: “1st Lt Jonathan Gillet 17th Contl Regt Died August 6, 1786,” initially supports that conclusion. But two other gravestones in the small cemetery at the foot of Grassy Hill leave room for doubt.

Gravestone, Lt. Jonathan Gillet, Laysville Cemetery

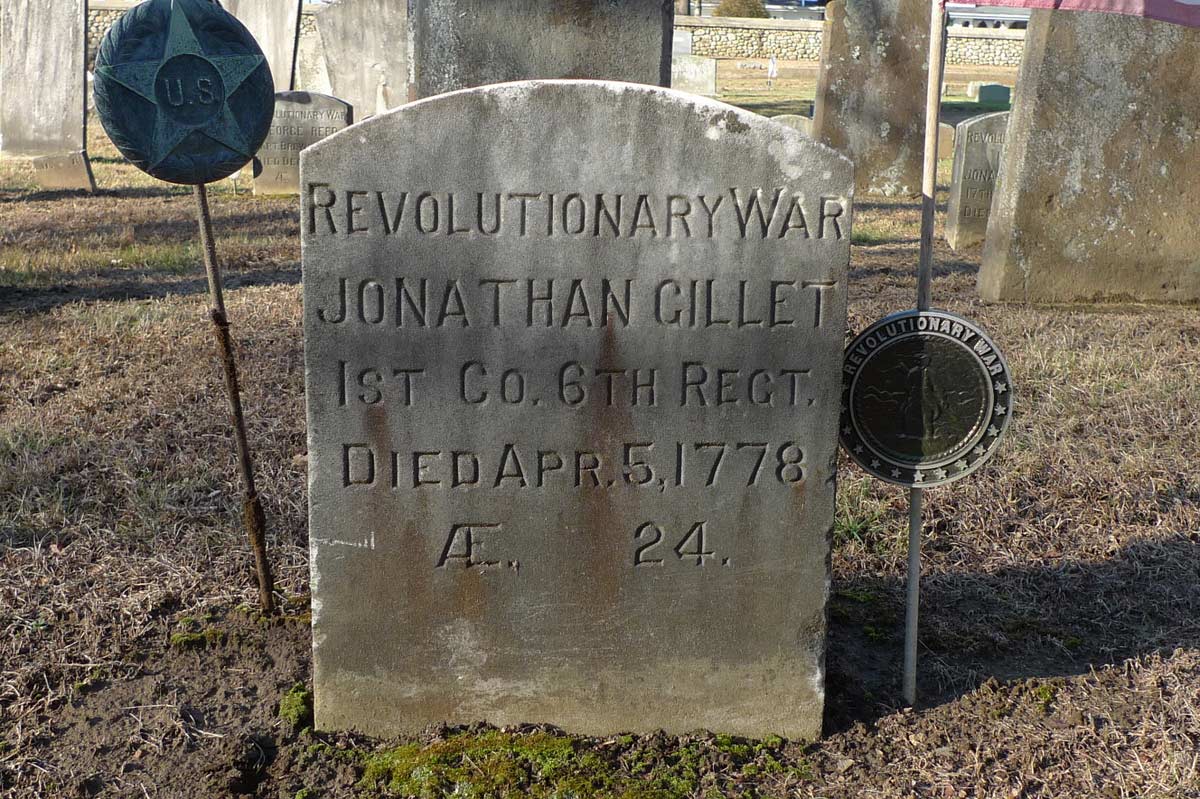

Beside it, a larger, more ornate monument decorated with a winged angel’s head commemorates: “Capt Jonathan Gillet departed this life on August 6th 1786 in the 67th Year of his Age.” The identical death date suggests that two markers may have been erected for the same person. Meanwhile a second veteran’s marker nearby honors: “Mr Jonathan Gillet: 1st Co 6th Regt Died April 5, 1778 Ae 24.”

Gravestone, Capt. Jonathan Gillet, Laysville Cemetery

Gravestone, Mr. Jonathan Gillet, Laysville Cemetery

Lengthy searches through vital records, military service records, land records, and family papers finally revealed the identities of three Revolutionary veterans named Jonathan Gillet buried in Laysville. In the confusion of wartime, military records listed the captured Lt. Gillet’s residence tentatively but inaccurately as Lyme.[13] That entry must have prompted the placing of a veteran’s marker with a borrowed death date in the Laysville burial ground. The imprisoned Jonathan Gillet who served in the 17th Regiment actually died in 1779 at age 42 after returning to his home near Hartford.[14]

Meanwhile the younger Jonathan Gillet who lived on Grassy Hill and served in the 6th Regiment in Boston [15] died in 1778 of unknown causes at age 24, just two weeks after he married Zilpha Pratt from Colchester. His father, the enterprising farmer, storekeeper, and militia captain who continued to enter charges in his account book throughout the war years, seems never to have left Lyme. Probate documents confirm that he died there in 1786 at age 67. [16] An article that appeared in The American Genealogist titled “There Are Too Many Jonathan Gillets in Windsor” could certainly be expanded to explain that there are also too many Jonathan Gillets in Lyme. [17]

[1] Carolyn Bacdayan, Bruce Stark, and Linda Winzer, as always, provided generous assistance. The 1742 deed and other family documents, unless otherwise noted, are included in the Gillet Collection, LHSA. For the auction listing click here

[2] For commercial development in Lyme, see May Hall James, The Educational History of Old Lyme, Connecticut, 1635-1935 (New Haven, 1939), pp. 82-84; Susan H. Ely and Elizabeth B. Plimpton, The Lieutenant River (Old Lyme, 1991), pp. 17-22.

[3] Lyme Land Records (LLR) 12:218, 13:116. In 1769 Elisha Seldon sold 30 acres with a small dwelling house and barn to John Peck, who then built “a handsome new house” with a taproom across from the parlor. See LLR 14:467; Susan H. Ely, “John Peck Tavern,” unpublished ms., LHSA. The Gillet papers show that John McCurdy did not run the only store between New London and Guilford, which has often been stated.

[4] Minor Myers, Jr., “Letters, Learning, and Politics in Lyme: 1760-1800,” in George Willauer, Jr., ed., A Lyme Miscellany, 1776-1976 (Middletown, 1977), pp. 56-59; Bruce P. Stark, Lyme, Connecticut: From Founding to Independence (Old Lyme, 1976), p. 50. Rev. Johnson’s letter “To the Freemen of the Colony of CONNECTICUT,” signed with the pseudonym “Addison,” appears in The New-London Gazette, September 6, 1765.

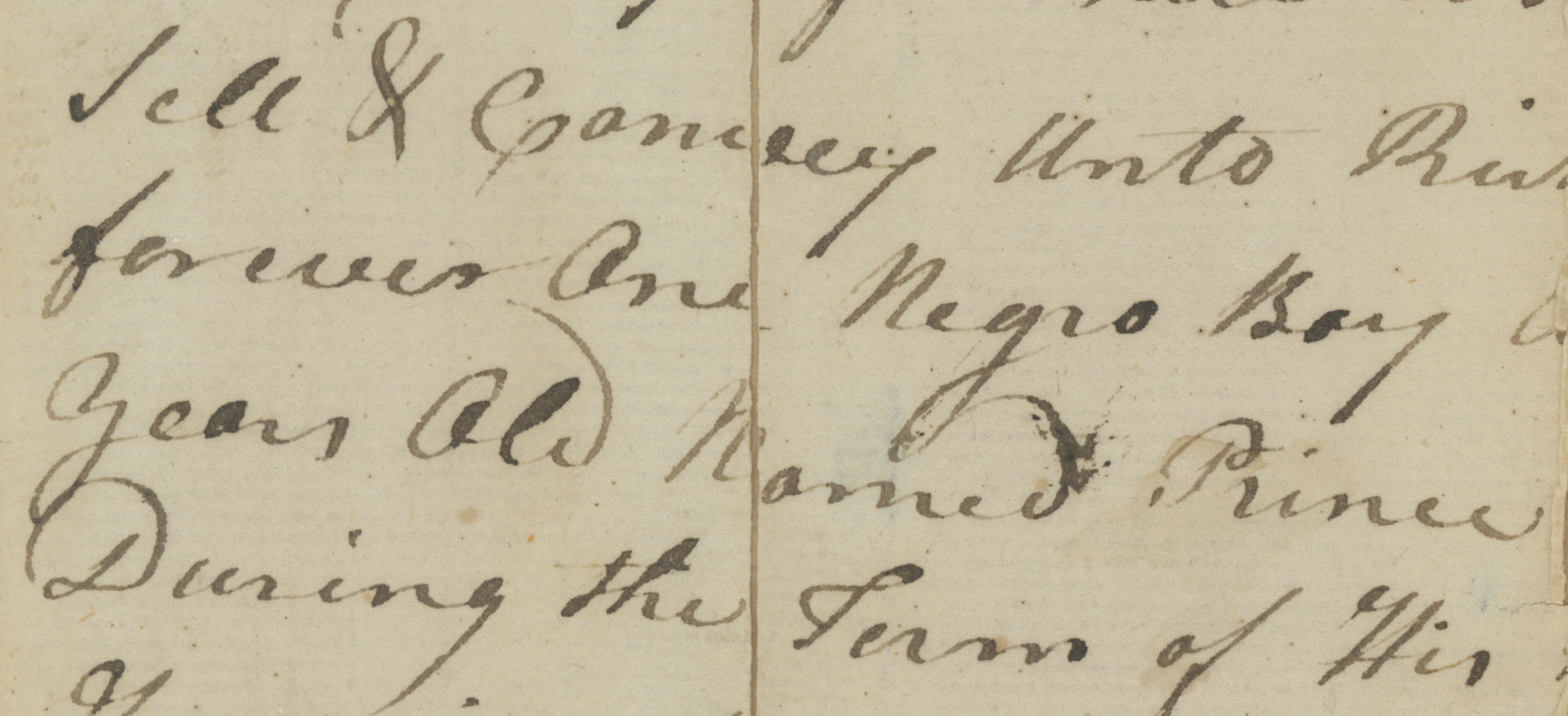

[5] The New-London Gazette, September 6, 1765; reprinted in Willauer, pp. 205-206. The 1756 census count listed 2,762 whites, 100 Negroes, and 94 Indians in Lyme. See Charles J. Hoadly, ed, The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut, from May 6 1751, to February, 1757, Inclusive (Hartford, 1877), p. 617.

[6] Hoadley, The Public Records of the State of Connecticut, From May, 1768, to May, 1772, p. 245: “This Assembly do establish Mr. Jonathan Gillet to be Lieutenant of the 3d company or trainband in the town of Lyme.”

[7] Connecticut Gazette, March 18, 1774; reprinted in Willauer, p. 238.

[8] Stark, p. 71.

[9] Minutes of the town meeting held on September 13, 1774, are transcribed in Willauer, pp. 240-241.

[10] Willauer, pp. 243-245.

[11] Col. Samuel Seldon, Lyme, to Capt. Joshua Huntington, Norwich, July 6, 1776; reprinted in Willauer, pp. 253-254. Henry P. Johnston, ed., The Record of Connecticut Men in the Military and Naval Service during the War of the Revoluton, 1775-1783 (Hartford, 1889), p. 101.

[12 Henry R. Stiles, M.D., Letters from the Prisons and Prison-Ships of the Revolution (New York, 1865), pp. 3-16.

[13] In his narrative account of wartime events in 1776, historian David McCullough describes British troops taking “swarms of prisoners” in the battle that raged on Long Island. His description of the stabbing of Capt. Joseph Jewett, whom he refers to as “Capt. John Jewett,” indicates a Lyme prisoner imprecisely identified after the defeat on August 27. See 1776 (New York, 2005), pp. 180-181.

[14] Stiles, pp. 3-16; George E. McCracken, “Too Many Jonathan Gillets in Windsor,” The American Genealogist, pp. 73-79. Photocopy courtesy Lyme Public Hall.

[15] Private Jonathan Gillet served in the 6th Regiment, 1st Company, commanded by Col. Samuel Holden Parsons, from May 8, 1775, to December 20, 1775. Rev. Stephen Johnson from Lyme served as regimental chaplain, and the company marched for five days from New London through Norwich and Providence to reach Boston near the end of the fighting. Only one private from Lyme, John Saunders, was wounded. See Johnston, p. 72; Charles S. Hall, Life and Letters of General Samuel Holden Parsons (New York, 1905), p. 32.

[16] The Gillet Collection includes a probate document dated September 11, 1786, regarding administration of the estate of Jonathan Gillet, “late of sd Lyme.”

[17] McCracken differentiates among fourteen Jonathan Gillets in the Windsor branch of the family but does not include the Gillets who settled in Colchester.