by Carolyn Wakeman

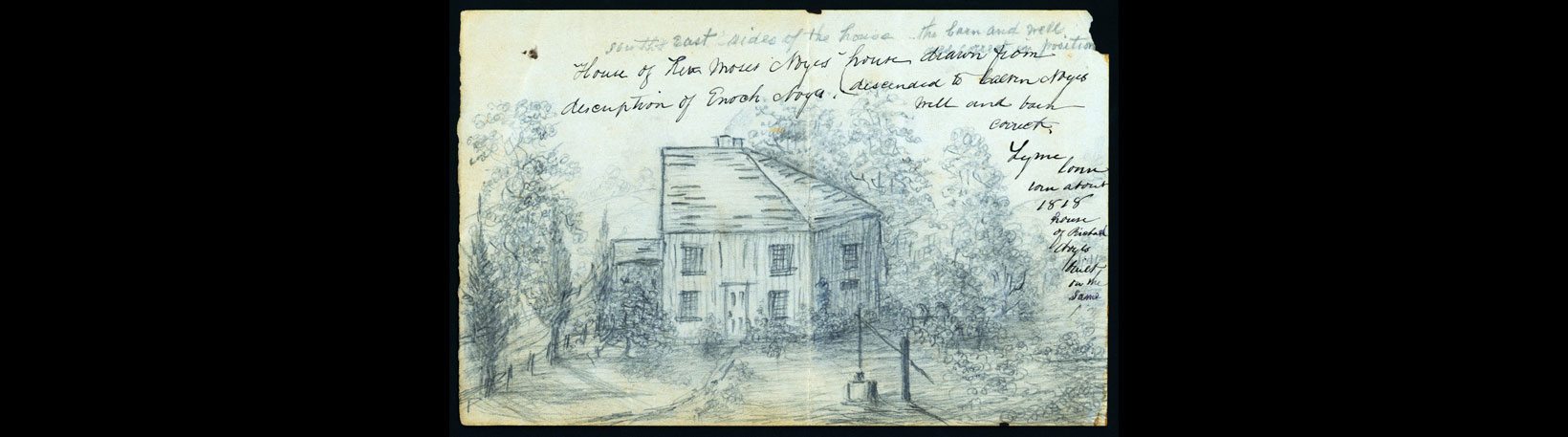

Feature Image (above): Ellen Noyes Chadwick, Drawing of Lyme’s first parsonage, ca. 1870. LHSA

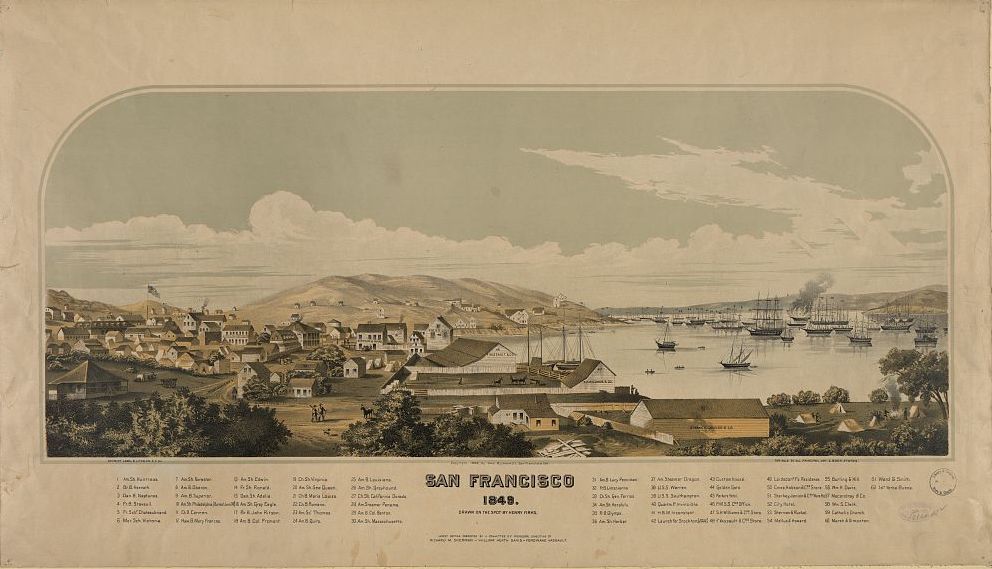

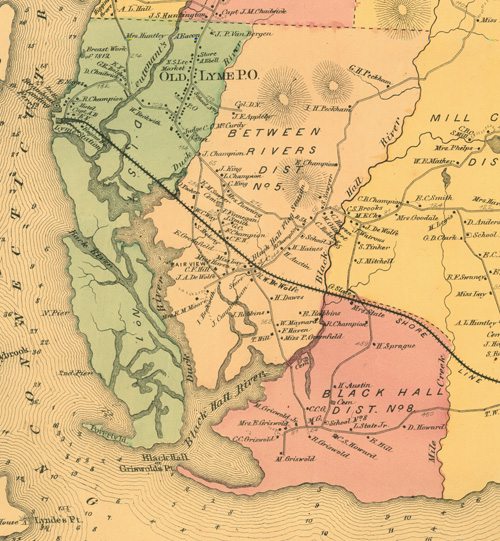

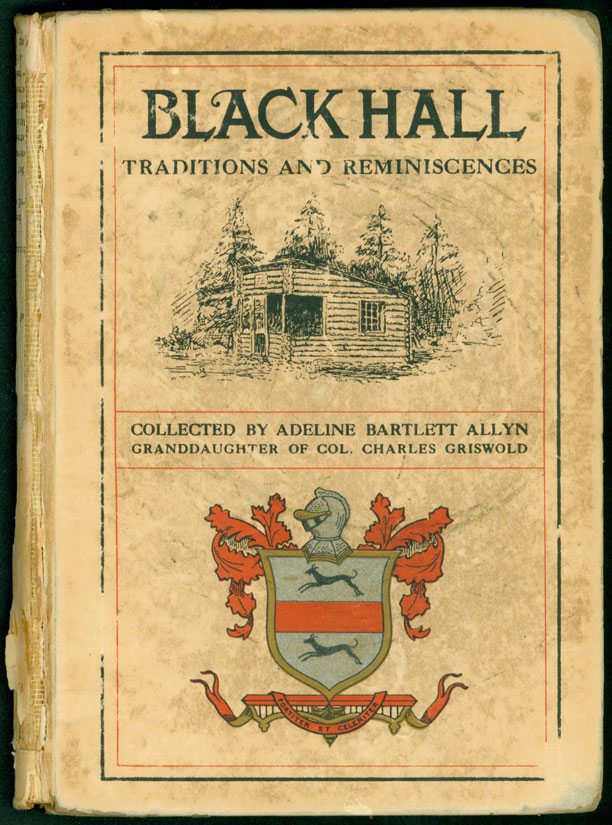

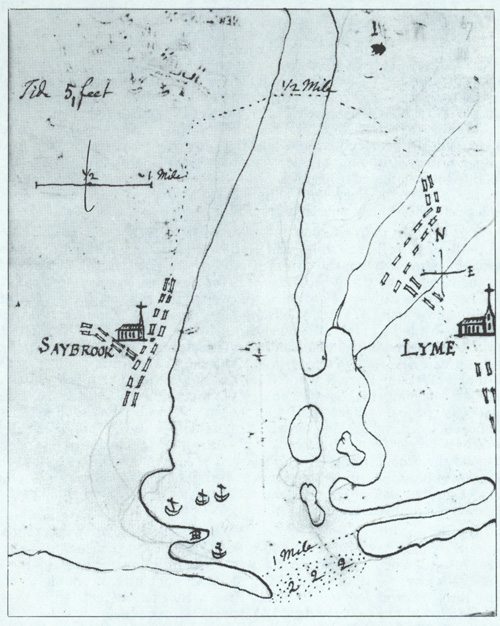

A Negro slave named Arabella, of unknown origin, served in Lyme’s first parsonage. There she attended Rev. Moses Noyes (1643–1729) and his family until she passed by will to his daughter Sarah. The original Noyes homestead has been demolished, but Arabella’s dwelling place can still be imagined from a sketch drawn by artist Ellen Noyes Chadwick (1824–1900), based on her father’s descriptions. Settling Lyme The early history of slavery in Lyme remains shadowy. Tradition has long held that the name Black Hall given to the large tract on the Connecticut River’s east bank where Matthew Griswold (1620–1698) settled derived from a black servant’s location there after 1640 to watch over farmed plots. Already in 1648 when the land on the east side of the “great Riuer” was set off from the original Saybrook settlement, the area “3 miles eastward and six milles northward [was] called blak hal quarter.” Two decades later a court summons establishes the first known Negro servant in the new “plantation” that was “for the future named Lyme.”[1]

Town of Old Lyme (detail showing Black Hall), F. W. Beers, 1868. LHSA

Black Hall: Traditions and Reminiscences, showing cover drawing by Charles Griswold Lane (1867–1896) that imagines the first Griswold slave’s dwelling. LHSA.

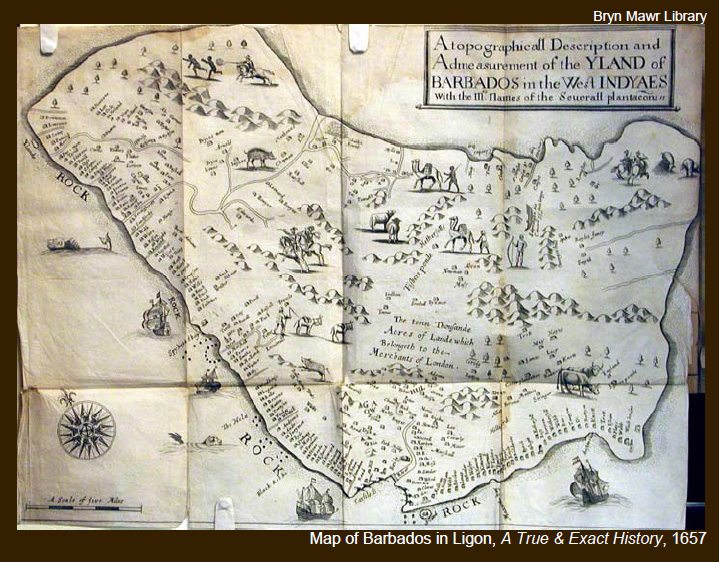

Slaves were widely viewed as an economic necessity in colonial New England. A letter to John Winthrop (1588–1649), governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, from his brother-in-law Emmanuel Downing (1594–1676) advised in 1645: “I doe not see how wee can thrive untill we get into a stock of slaves suffitient to doe all our buisines.” Two of the governor’s sons became West Indies’ planters, but John Winthrop, Jr. (1606–1676), followed his father to New England, oversaw the building of a fort at Saybrook, founded a settlement at New London, and performed a marriage beside a stream now in East Lyme called Bride’s Brook.[2]

Illustrated Map of Barbados, from Richard Ligon, A True and Exact History of Barbados,1657. Bryn Mawr Library

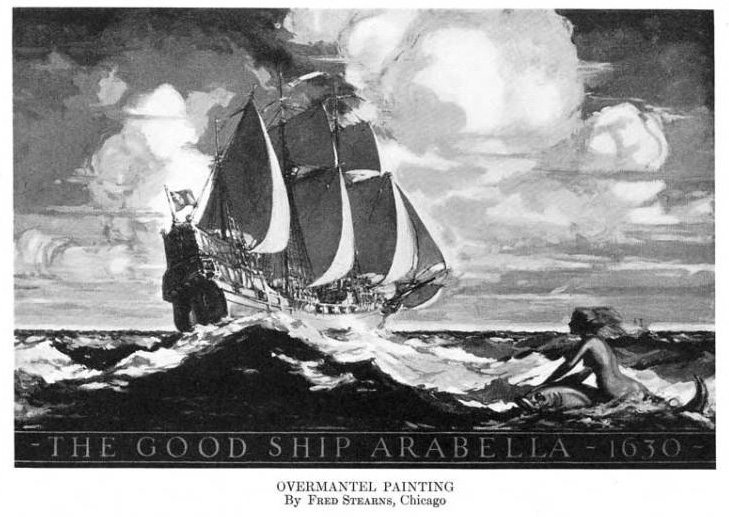

The younger Winthrop also received advice about the economic benefits of slavery. A cousin wrote from Barbados in 1645: “they have bought this year no lesse than a thousand Negroes and the more they buie, the better able they are to buye. For in a yeare and a halfe they will earne (with gods blessing) as much as they cost.” By then a few slaves already contributed to the labor force in Connecticut, appearing first in Hartford in 1639 and later in New Haven in 1644.[3] The Negro servant at the Lyme parsonage was likely named after the ship Arabella that carried the elder John Winthrop to New England in 1630. Whether the slave Arabella came directly from Barbados or landed first in Boston is not known. Rev. Moses Noyes had grown up in Newbury, Massachusetts, where his father was a prominent clergyman, and graduated from Harvard at age 16. His youthful sermons in Boston had already established his reputation for learning and eloquence when he reached the settlement at the mouth of the Connecticut River that then numbered thirty families. Rev. Noyes began preaching at age 23 in a small Meetinghouse built from rough-hewn clapboards on the crest of a hill. He was over thirty when he married Ruth Pickett (1653–1690), daughter of a wealthy New London merchant who died at sea on a passage from Barbados. The town granted him an expanse of salt meadow and a 60-acre home lot to secure his settlement in Lyme, and he later added substantially to his properties. A local church historian, inquiring what terms would have “induced the young minister to leave his comfortable home in Newbury to become the Pastor in Lyme,” concluded that “land seemed to be the main consideration.”[4]

Ezra Stiles, Map showing the mouth of the Connecticut River and location of Lyme’s first Meetinghouse, 1768. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

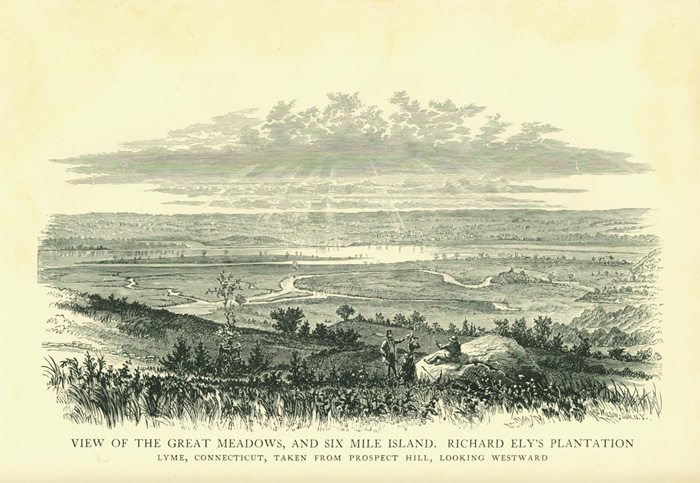

Whether other servants besides Arabella assisted in the Noyes household, harvested salt hay from the acreage on Great Island, or helped maintain the 90-acre parsonage farm during his 63-year ministry is not known. His brother Thomas Noyes (1648–1730), who inherited their father’s house in Newbury, owned two slaves.[5] Early Slavery in Lyme Slavery in seventeenth-century Lyme is sparsely documented, but Arabella and other early servants left traces. The New London County Court case confirms that Richard Ely (1625–1684) had already purchased at least one Negro to work on his 3,000-acre estate before 1670. The court summons that year required that he and his wife, along with “ye negro servant Moses,” answer a complaint from the town constable about the “prophanation of the Sabath.”

Richard Ely’s Six-Mile Plantation, Lyme, Connecticut. From Moses Beach, The Ely Ancestry (1902). LHSA.

In 1675 Ely owned at least two slaves when he deeded to Richard Lord (1647–1727) “all my lands in the east side of the River, of Connecticut with all the housing fenceing cattle horses household goods and my tow Negers excepting and still reserving my wifes interest in my estate aforesaid.” It is thought that his eldest son William, before joining his father in Lyme, spent two years in Barbados entrusted to his uncle James Ely (–1688).[6]

West Indies sugar-cane plantation, from Jabez Marrat,In the tropics: or, Scenes and incidents of West Indian life. New York Public Library Digital Collection

Trade between the Lyme region and the West Indies began two years after Saybrook’s “outlands” were divided. Captain Greenfield Larrabee (1620–1661), an early proprietor who chose property on the east side of the river, carried local barrel staves to the islands on the shipTryall in 1650, presumably in exchange for sugar and rum.[7] Horses, needed for transport and the operation of heavy sugar presses, proved another valuable commodity in the early coastal trade. Richard Ely’s kinsman John Ely, a Boston merchant living temporarily in Saybrook, sent a shipload of horses raised by local landowners to Barbados soon after Rev. Noyes settled in Lyme. Each sorrel or roan was described by color, identifying features, and the owner’s specific ear mark. Ely sent a horse of his own with Captain John Chester on the ketch Dilligent in 1666 and stated his preference for payment in rum: “…in case my roan horse which I send by you as an adventure should come safe alive—at Barbadus that then you will use your utmost to dispose the same to sale for me for my utmost advantage for good Rum or else part rum and part sugar and to consign it to myself in Boston in the first vessel bound thither.”[8] Whether local mariners returned from Barbados with slaves as well as sugar and rum is not known. In a detailed history of Lyme families published in 1892, Edward and Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury offer only anecdote: “It is said that, in early times, cargoes of negro slaves were brought up the Connecticut River, and sold out from place to place.”[9] Slavery’s Traces As the coastal trade increased, barrel staves and livestock left Lyme in growing quantities, along with farm products that provisioned island plantations and barreled shad, considered the cheapest food for slaves. Growing commerce required new roads, bridges, wharves, warehouses, mills, fisheries, and shipyards. In 1710 the population numbered 750, and more slaves left traces in town.

Edward Rook, Bradbury’s Mill,ca. 1915. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company

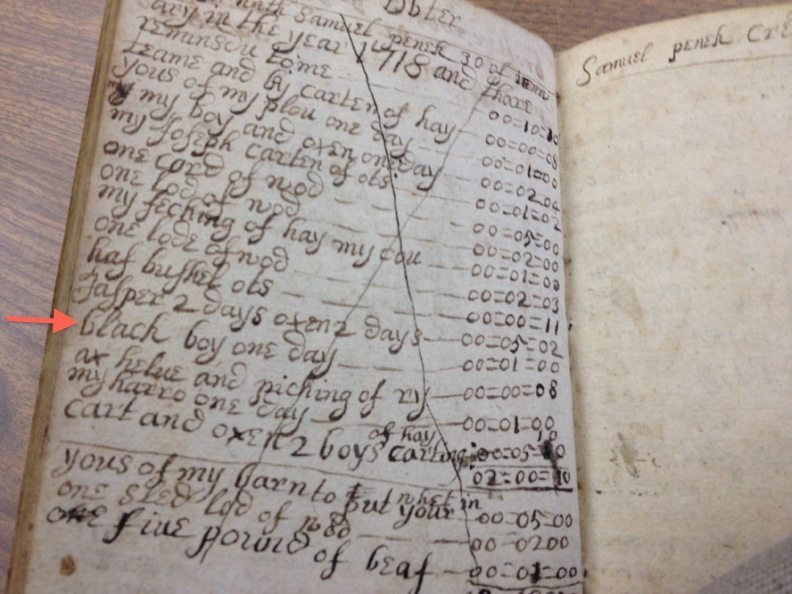

Edward DeWolfe (1646–1712), a skilled carpenter and millwright who built houses, repaired bridges, and furnished shingles and clapboards for a second Meetinghouse, owned at least one slave. His gristmill ground corn for the town three times a week, while his saw mill on Mill Brook produced boards and barrel staves. A court document in 1704 details an accusation from John Rayner in Lyme that Mingo, DeWolfe’s servant, had tried to kill him. Twenty-seven men from Lyme signed a petition attesting to Mingo’s good character that stated: “wee do nott Know of any Wronge that hee hath Dun to any person . . . Since hee Came to This Town.”[10] Trial records have not survived so Mingo’s verdict is unknown, but town meeting minutes document the rapid growth of barrel stave exports. In 1709 the town authorized Captain John Clark of Saybrook “to transporte Thirteen Thousands of Hogsed Staves which nine thousand of Them are upon Edward Dewolfes account.” At the same meeting it granted liberty to Richard Ely’s son William (1647–1717) “to tranceport from Lyme thirty three thousand of hogsed and barril stavs.”[11] DeWolfe’s eldest son Charles, also a carpenter, assisted with the work of the sawmill, but his grandson Charles, born in Lyme in 1695, sought new opportunity. At age 22 he left home to settle permanently as a trader and millwright on the French island of Guadeloupe. The DeWolfe family later became the primary importers of slaves to Rhode Island.[12] A year after the younger Charles DeWolfe reached Guadeloupe, an account book kept by Joseph Peck, Jr. (1680–1757), recorded receipts for hired Negro labor in Lyme. Peck itemized charges in 1718 of one shilling for a “black boy one day” and three shillings for a “black boy one day [with] harro.” By then, Peck had inherited his father’s warehouse and dwelling (now demolished), which stood to the south of Rev. Noyes’ parsonage and served as a tavern or “ordinary.”[13]

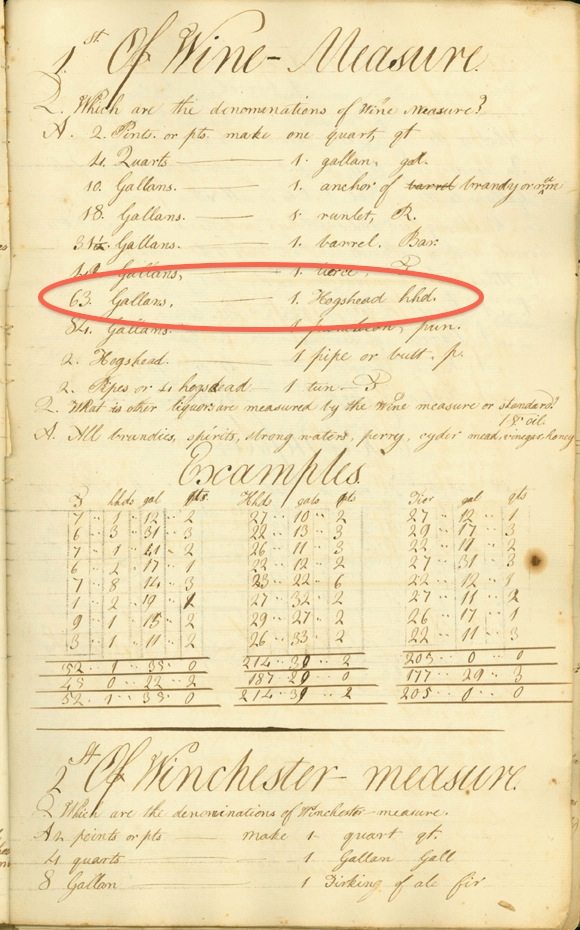

William E. Coult’s Book, showing mathematics lesson about wine measurements, ca. 1823. LHSA

Joseph Peck, Account book, 1718, showing receipt for hired Negro labor. Connecticut State Library Manuscript Collection

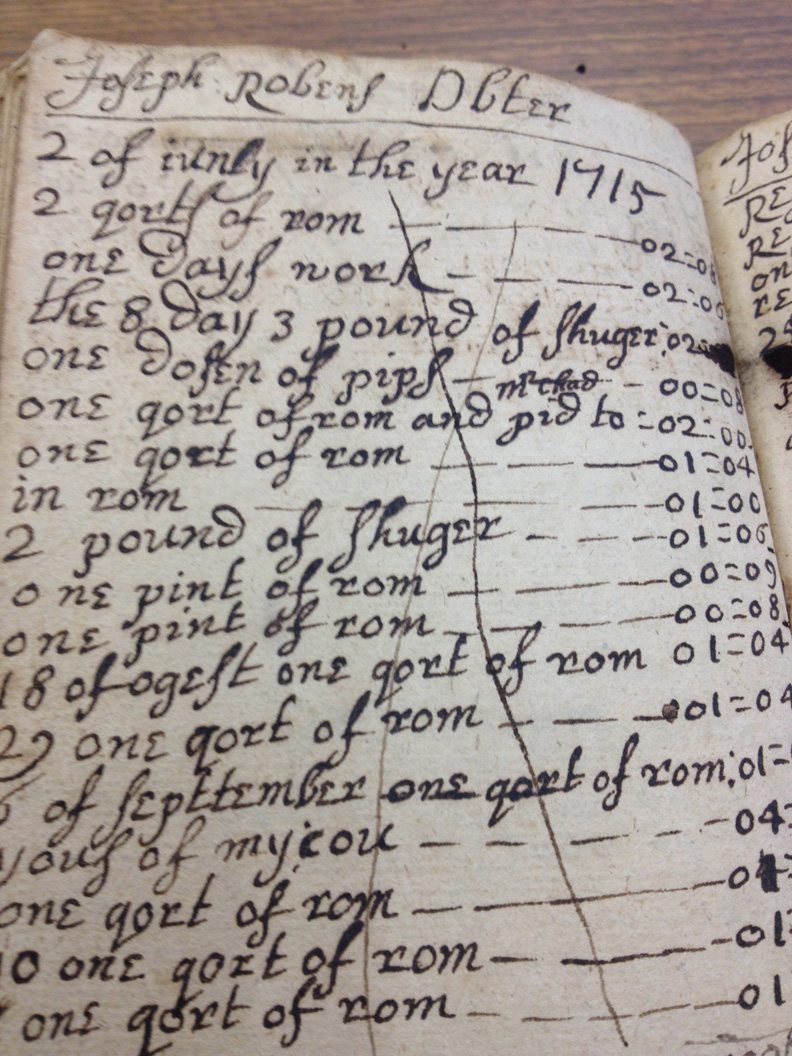

Joseph Peck, Account book, 1715, showing sales of sugar and rum. Connecticut State Library Manuscript Collection

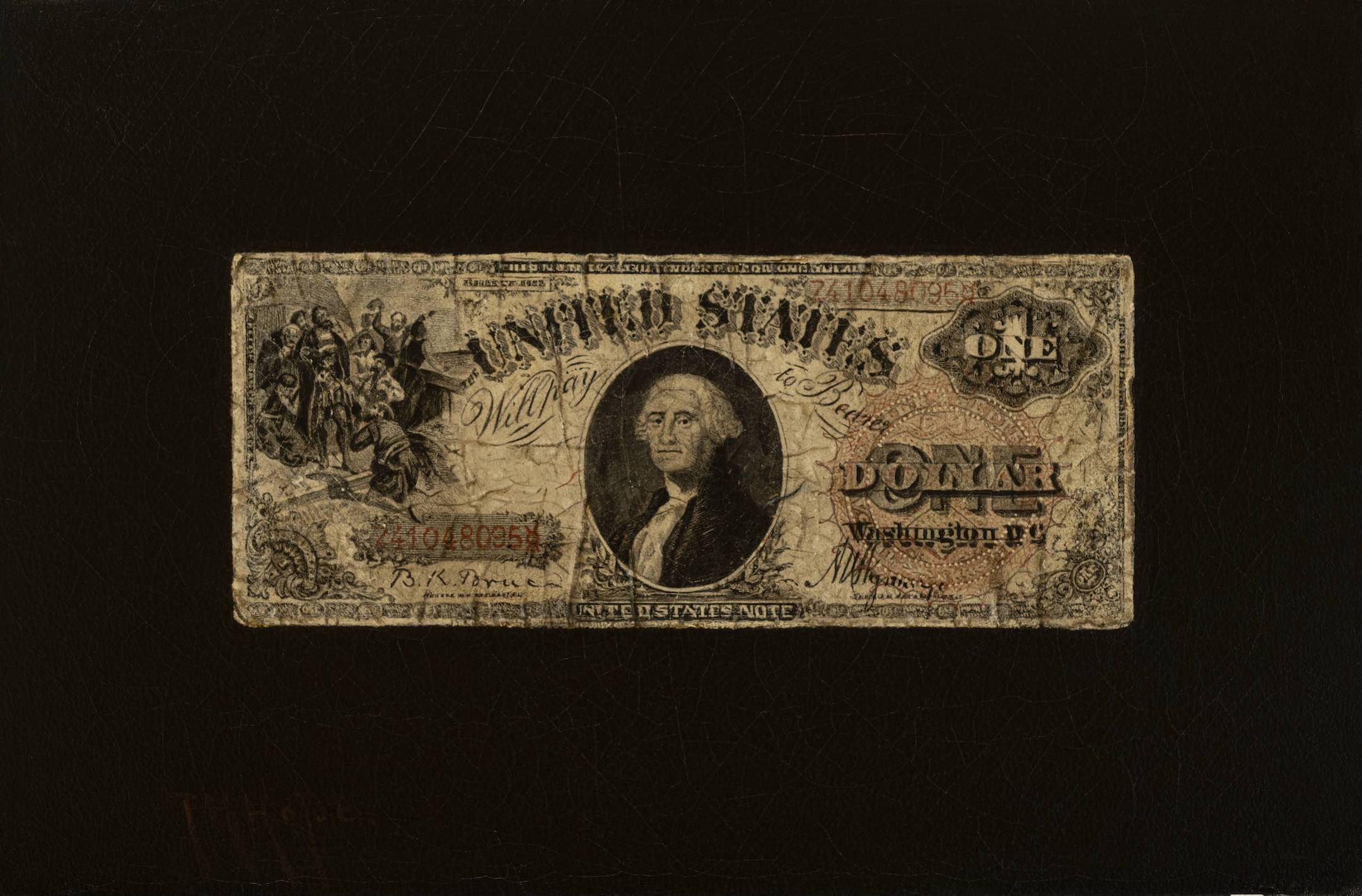

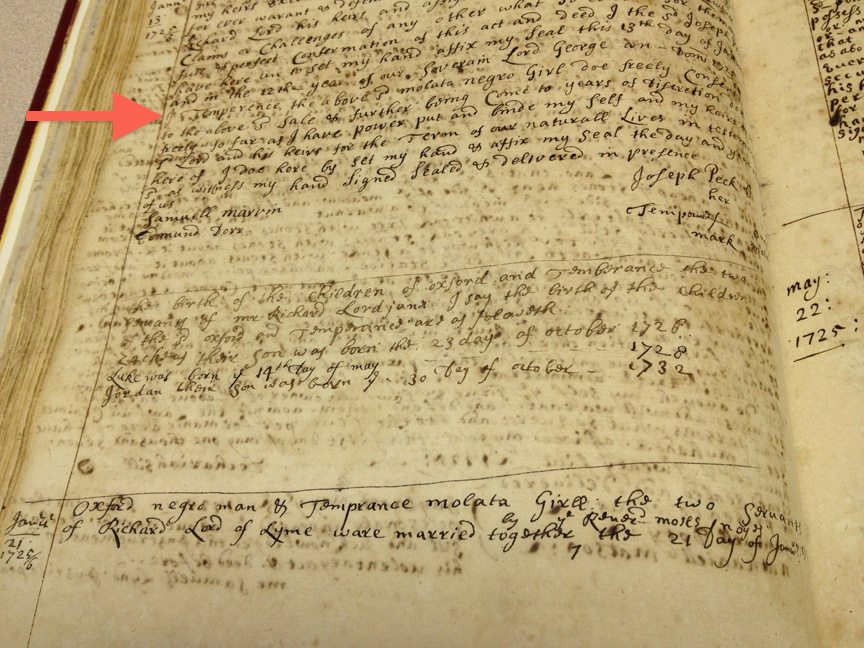

In 1715 the younger Peck was already selling large quantities of rum by the pint and the quart as well as sugar by the pound. In addition to hiring out his plow, harrow, and ox team, he delivered wood by the sled load, provided hay storage in his barn, and sold wheat, oats, and beef. On at least two occasions he also sold slaves. In 1726 “For the consideration of the sum of Sixty pounds in Bills of Publick credit of the coloney of Conecticut to me in hand paid by Richard Lord Jun,” Peck sold: “A Certain molato Negro Girl named Temperance after the maner of a negro slave to Serve the sd Richard Lord his heirs and Assignes. . .during the Term of her natural Life.” Declaring that he was “the sole proprieter and Lawfull owner of the sd negro girl,” Peck stated his “good right & Lawfull authority [to] alieneate and Sell the sd negro girl.”[14]

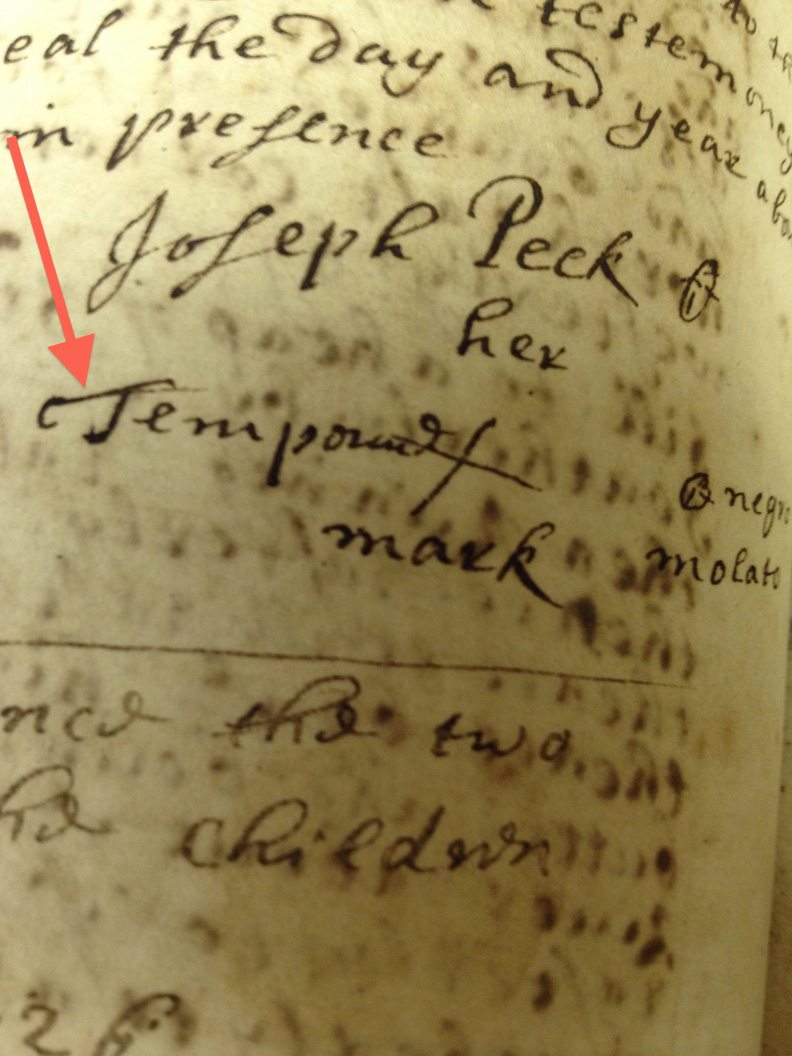

Slave Deed of Sale, January 13, 1726, Lyme Land Records

Temperance, age 20, consented to her purchase: “I Temperence the above sd molato negro Girl doe freely consent to the above sd sale & further being come to [my] years of discretion doe freely so far as I have power put and binde my self and my heirs to the sd Lord and his heirs for the term of our naturall Lives in testimony here of I doe here by set my hand & affix my seal.” Below Joseph Peck’s signature “Temperance negro molato” marked an X.[15]

Slave signature consenting to sale, January 9, 1729, Lyme Land Records

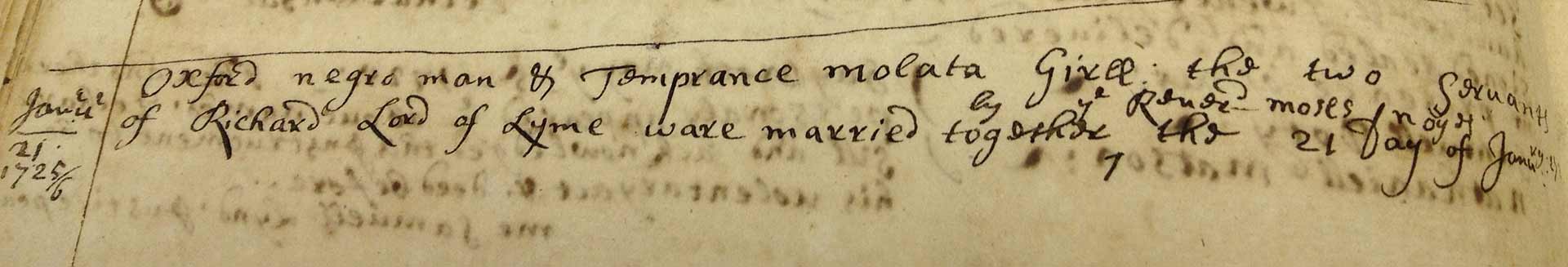

One of the elderly minister’s last official acts was to marry two slaves. A week after Temperance was sold: “Oxford negro man & Temprance molato girl the two servants of Richard Lord of Lyme were married together by ye Revd Moses Noyes the 21 day of January.” The town paid a bounty of four shillings to “Oxford negro man” for bringing in two fox heads in 1728. By then the servant couple had heirs. Zachery and Luke were born in 1726 and 1728 followed by Jordan in 1732.The birth date of a daughter Abiah is not known, but her baptism in 1731 appears in church records.[16] The four children remained legally bound in servitude to Judge Richard Lord (1690–1776) for the term of their natural lives.

Record of slave marriage, January 26, 1726, Lyme Land Records

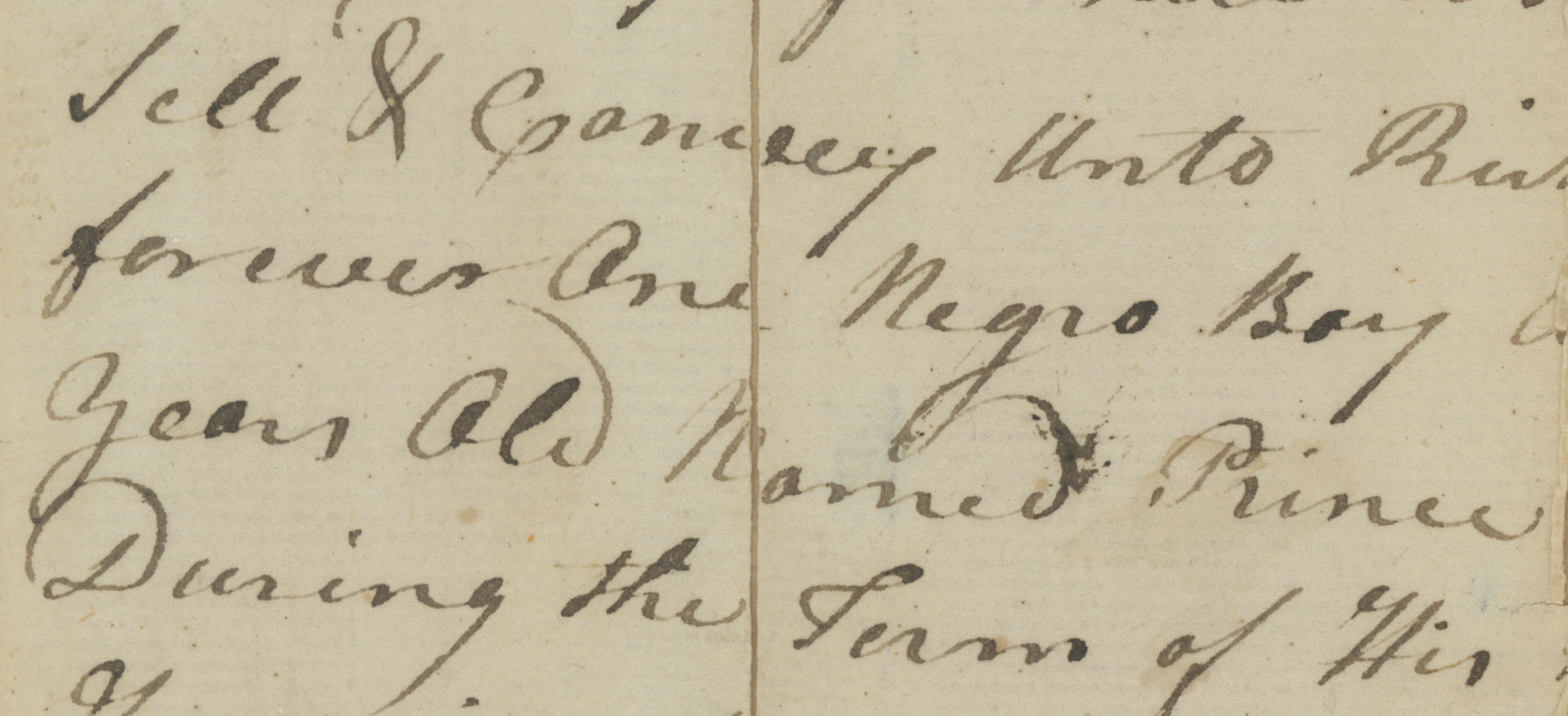

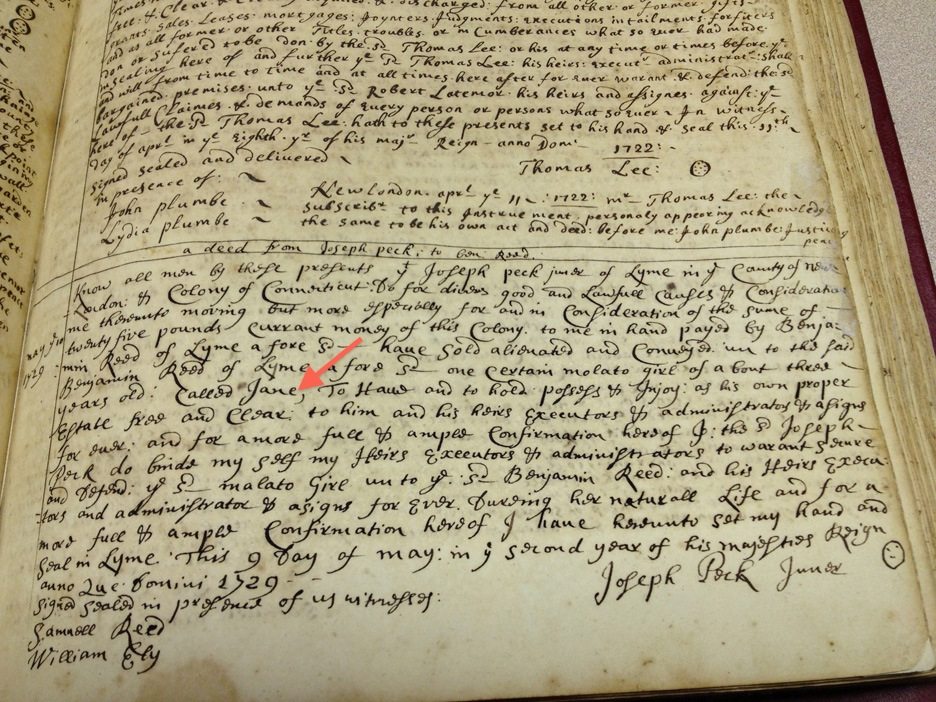

Besides Temperance, “Joseph Peck Junr of Lyme” sold at least one other slave, a child. “In consideration of the sum of twenty five pounds…payed by Benjamin Reed of Lyme,” he made over in 1729 “one certain molato girl of about three years old: called Jane, To Have and to hold possess & injoy as his own proper estate free and clear…for ever during her naturall Life.” Jane’s parents are not known, nor is the date that Peck acquired a slave named Jack. Church records note only that “Jack man servant of Joseph Peck” died in 1738.[17]

Deed of Sale, January 9, 1729, Lyme Land Records

Judge Lord retained the slave couple for nine years. In 1735 he sold Temperance, age 29, Oxford, age 29, and their infant son Joell, age seven months, “all sound and in good health to ye best of my knowledge,” to Judge John Bulkley (1704–1753) of Colchester for 180 pounds. The deed of sale stated Richard Lord’s “good Right, full power and Lawfull authority to Sell said Man, Woman and Child, as Servants, during the Term of their naturall Lives,” and he obligated himself and his heirs forever to defend them as Bulkley’s slaves “against all…Endeavours of sd Slaves to free themselves.”[18] Whether Judge Lord also sold Abiah, or Zachery, Luke, and Jordan who were nine, seven, and three when their parents were purchased and removed from Lyme, is not known. The Salisbury family histories describe him as a genial man who “had a large household, with many slaves.”[19] Noyes Bequests Perhaps twenty adults and children remained in servitude in Lyme, along with Arabella, during Rev. Noyes’ ministry. When she passed by will to his daughter Sarah Noyes Mather (1683–1756) in 1729,[20] his sons had also acquired slaves. Whether any were Arabella’s children or grandchildren has not been documented, but the Negro woman in the minister’s household, like Temperance, would probably have produced heirs. When Sarah’s younger brother Dr. John Noyes (1687–1733) died at age 45, he left to his wife Mary Hudson Noyes (1705–1773): “negro boy called ‘Caesar’ negro girl called ‘Grace.’” His estate inventory lists: “one Negro youth called Warrick and one negro Girl calld Grace,” valued at 200 pounds. Two years later when “ye widow Noyes” remarried, her slaves became the property of her second husband William Ely, Jr. (1683–1759). His gravestone inscription states: “He was amongst the first who gave Freedom to his slaves, Therein doing as he would be done by,” but how many slaves he freed is uncertain. Grace died in 1734, but according to the terms of his will, Warrick and Caesar passed again to the twice-widowed Mary Noyes Ely.[21] By the time Sarah’s older brother Moses Noyes 2nd (1678–1743) wrote his will at age 75, he also had three slaves to distribute. Called Squire Noyes, he lived with his family and his slaves in a house built about 1726 on the site of the present Florence Griswold Museum. His will left to his “dear and loving wife” Mary Ely Noyes (1689–1764), a slave youth, “Richard Jimie (by name) until he comes of age.” To his son Moses 3rd, in addition to the homestead, Squire Noyes gave his “Negro man Jube, reserving half his time for six years which I give to Willm after he comes of age.” His unnamed “negro woman” passed to his wife and two daughters. The estate inventory valued “one Negro Man Servant named Jube” at 35 pounds.[22]

Old Mather house (now demolished) near the ferry on what was called Mather’s Neck. LHSA

Church records show that Arabella was baptized in 1734. Referred to as “Bella, (Sev’t of T. Mather),”[23] she had moved by then from the parsonage to Sarah Mather’s house above Lyme’s ferry landing. Sarah’s husband Timothy Mather, Jr. (1681–1755), a nephew of the renowned Boston minister Cotton Mather, was elected to several town offices and had continuing contact with Lyme’s early slaves. While serving as town constable in 1740, he boarded for eight months a negro man belonging to Thomas Clements. And when he appraised the estate of Daniel Sterling in 1747, he valued a Negro manservant at 250 pounds.[24] At age 74 Mather drafted his own will. To his wife Sarah he left one-third part of his farm “& the negro woman during the natural life of her mistress. If the negro woman outlives the widow she can live with either of my children which she shall choose but if the sd negro woman be not able to maintain herself then it is my will that my son Joseph maintain her at his own cost during her natural life.”[25] Sarah Mather died in 1756, a year after her husband. The date of Arabella’s death has not been found.

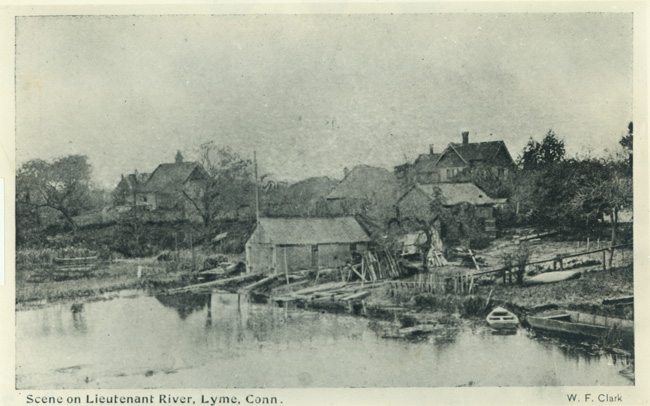

Remains of warehouses along Lieutenant River, ca. 1900. LHSA

Although the Noyes family kept multiple servants, they were hardly alone in their slaveholding. As the town grew and prospered, governors, judges, military officers, ministers, deacons, doctors, merchants, mill owners, tavern keepers, and well-to-do farmers all owned slaves. Sea captains, shipyard owners, ship’s joiners, deckhands, coopers, blacksmiths, carpenters, mill workers, farmhands, shad fishermen, and day laborers benefited, in turn, from Lyme’s coastal trade.

[1] Special thanks to Bruce Stark, former Assistant Connecticut State Archivist; Betsey Webster, historian of the First Congregational Church of Old Lyme; Linda Winzer, Town Clerk of Lyme; and Carolyn Bacdayan, archivist at the Lyme Public Hall, for generous assistance in documenting the history of slavery in Lyme. Cited in Bruce Stark, Lyme, Connecticut: From Founding to Independence (Lyme Tercentenary Committee, 1976), p. 1.In Black Hall: Traditions and Reminiscences (Hartford, 1908), pp. 9-10, Adeline Bartlett Allyn notes that the name Black Hall could also be an adaptation of an English place name, like Black Friars Hall near Kenilworth or Black Hall Farm in Kent. See also New London County Court records, 1670, III:21.

[2] Downing suggested that a “just war” with the Narragansetts could provide captives and those men, women, and children could then be exchanged for “Moors.” Emmanuel Downing to John Winthrop, August 1645, in Winthrop Papers, 1645-1649 (Massachusetts Historical Society, 1947), V:38. The governor’s son Henry Winthrop had tried unsuccessfully to establish a tobacco plantation in Barbados from 1627 to 1629, but his son Samuel Winthrop settled permanently in 1647 as a planter in Antigua and served for three years as its Deputy Governor. When he died in 1674, his estate included 1,100 acres and 64 Negroes. See Richard S. Dunn, Sugar & Slaves: The Rise of the Planter Class in the English West Indies, 1624-1713 (Durham, N.C. 1972), pp. 50, 125-6. See also D. Hamilton Hurd, History of New London, Connecticut (Philadelphia, 1882), pp. 137-8; Frances Manwaring Caulkins, “Bride Brook,” in The History of New London, Connecticut (Hartford, 1852)

[3] Rev. George Downing to John Winthrop, Jr., August 26, 1645, cited in Dunn, p. 68. Winthrop’s cousin had served as a ship’s chaplain on his passage to Barbados.

[4] The ship was named for one of the wealthiest of the Puritan emigrants on that voyage, Lady Arabella Johnson (–1630), who died a few months after arriving in Salem. See Charles Ripley Damon, The American Dictionary of Dates (Boston, 1921), p. 26. A biographical sketch of Rev. James Noyes (1608–1656) appears in Charles Phelps Noyes and Emily H. Gilman, Noyes-Gilman Ancestry (St. Paul, 1907), pp. 5-12. See also Willis H. Umberger, ed., History of the First Congregational Church of Old Lyme, Connecticut, 1665–1993 (Old Lyme, 1995), pp. 9-36; 24.

[5] Noyes and Gilman, p. 16.

[6] New London County Court records, 1670, III:21; Lyme Land Records (LLR) 1:37; Moses S. Beach and Rev. William Ely, The Ely Ancestry (New York, 1902), p. 38.

[7] Thomas A. Steeves, “Old Lyme: A Town Inexorably Linked to the Sea,” (Old Lyme, 1959), pp. 7-8.

[8] John Ely in Boston and James Ely in Barbados may have been Richard Ely’s brothers. LLR, 1:65.

[9] Edward and Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury, Family Histories and Genealogies (New Haven, 1892), I:138 .

[10]Bruce P. Stark, The New London County African American and People of Color Collection, 1701–1854. Connecticut State Library (2008). John Rayner (1667–) seems to have left Lyme in about 1717 when he sold his property to his brother Josiah.

[11] Edward DeWolfe’s Lyme properties and authorizations from the town are variously documented in land records and town meeting records. See Jean Chandler Burr, ed., Lyme Records, 1667–1730 (Stonington, 1968), p. 121.

[12] The slave trading of Mark Antony DeWolfe and his son James DeWolfe, who became a U.S. Senator from Rhode Island, are documented in George Howe, Mount Hope: A New England Chronicle (New York, 1959), Calbraith Bourn Perry, Charles DeWolf of Guadaloupe [sic]: his ancestors and descendants (New York, 1902).

[13] See Joseph Peck account book, Connecticut State Library Manuscript Collection. Forty years earlier the New London County Court had given permission to his father Ensign Joseph Peck to sell “cyder by retail during the want of an ordinary,” since there was no “house of common entertainment” in town. Cited in Ely-Plimpton Papers, Box 2, LHSA. Joseph Peck, Sr., relinquished his position as ordinary keeper in 1702, and the town voted “that Thomas Anderson shall have liberty to sell about one hundred gallons of Rume: out of Jares by the gallon or quart.” See Burr, p. 93.

[14] LLR 4:170.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.; Burr, p. 173; Umberger, p. 241.

[17] LLR 4:79; Umberger, p. 307.

[18] Cited in Salisbury, I: 293-4.

[19] Ibid., p. 138.

[20] Photocopy in Ely-Plimpton Papers, Box 6, LHSA.

[21] New London Probate Record 1733, #3840, Connecticut State Library; Beach and Ely, p. 34; Umberger p. 306; New London Probate Record 1759, #1945: “I do hereby Give and bequeath to my beloved wife Mary my two Slaves (viz) Warrick and Teazor [Caesar] to be at her own Disposall for Ever,” Connecticut State Library. Also see Barbara W. Brown and James M. Rose, eds., Black Roots in Southeastern Connecticut, 1650–1900 (Detroit, 1980), p. 586, and John Pfeiffer, “Slavery in Southeastern Connecticut: A View from Lyme” (unpublished ms, 2009), p. 4.

[22] New London County Probate Record, 1743, #3846, Connecticut State Library.

[23] Umberger, p. 242.

[24] See Timothy Mather v. Thomas Peck, in Stark, The New London County African American and People of Color Collection; and Mary Sterling Bakke, A Sampler of Lifestyles: Womanhood & Youth in Colonial Lyme (New Haven, 1976), p. 63.

[25] Timothy Mather’s will, dated September 22, 1750, and proved on August 26, 1755, is transcribed in Ely-Plimpton Papers, Box 5, LHSA.