by John E. Noyes

Featured Image: Charles H. Davis, Hillside Road, Mystic, Connecticut, 1924. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, 2002.1.43

Charles H. Davis’s Hillside Road, Mystic, Connecticut (1924), on display at the Florence Griswold Museum’s Art and the New England Farm exhibition, reflects a nostalgic view of a vanishing way of life. Prominent in Davis’s painting is a stone wall, so common in the New England landscape and a symbol of the industry and self-reliance of the New England farmer.

Early Connecticut settlers deforested large tracts of land, clearing pastures and fields for crops and providing wood for housing, shipbuilding, fencing, and fuel. When the land was first cleared, a dense layer of plant detritus, built up over millennia, covered many glacial rocks. Erosion, aided by grazing and plowing, gradually removed the topsoil and uncovered these rocks. The newly unprotected soil would also freeze deeply in the winter, and frost heaves moved stones upward at a rate of several inches per decade. Farmers then had to remove what seemed to be a yearly crop of rocks from their fields.[1]

Old Lyme barn with rock and stone wall. LHSA at FGM

The rocks found use in house and barn foundations, in animal pounds, and in stone walls. Double-width stone walls were commonly built along roadways and on formal estates. Single-width walls often marked the edges of small fields within a farm or boundaries between landowners.[2]

John Ludlow Morton, View of the Schoolhouse at Green’s Farms, 1840. Oil on canvas. FGM, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, 2002.1.98

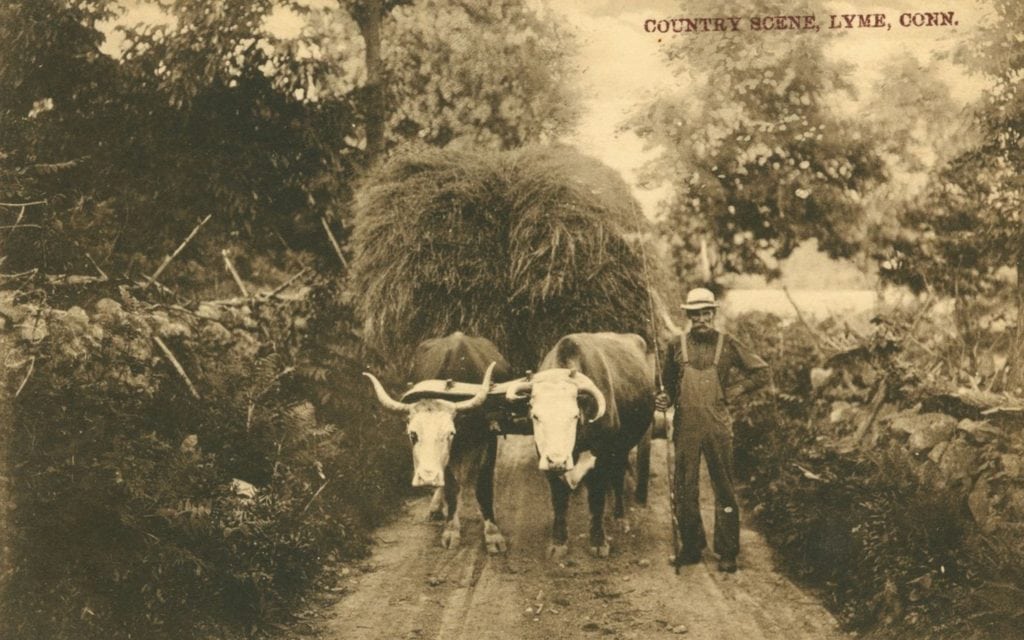

Country Scene, Lyme, Conn., ca. 1900. Postcard. LHSA at FGM

When farmers cleared a field, they hauled brush, stumps, and rocks to its edges. Later, they moved more stones to these field edges and built walls. The distance that men working with a team of oxen and a wooden sledge could efficiently haul heavy stones limited the size of New England fields, and the weight of stones limited the height of walls.[3] Around fields stone walls, which were usually no more than two or three feet high, were often topped with wood fencing (and later with wire) in order to confine animals or keep them away from crops.[4]

Stone and wood fence, seen in Nelson A. Moore, Apple Orchard, 1878. Oil on canvas. FGM, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, 2002.1.96

Stone walls supplemented with wood fences, near Rogers Lake, Old Lyme, Connecticut, 1905. Lyme Historical Society Archives (LHSA) at the Florence Griswold Museum (FGM)

Although the half century from 1775 to 1825 marked the most active period of stone wall construction in New England,[5] coastal Connecticut farmers were building stone walls early in the eighteenth century.[6] Joshua Hempstead of New London wrote that on April 23, 1718, he was “at home al day helping Nathll Holt Make Stone wall between the orchard and ye lot from the Rocks 4 rods downwards.”[7] Hempstead’s scores of diary entries about digging stones and building or mending walls were unusual; most early diaries and agricultural magazines either omitted or barely noted these ordinary chores. Landowners and their families did much of the work building stone walls; children too young to move stones might be enlisted to dig trenches for walls.

Some landowners, including Joshua Hempstead, could also afford to hire help to build stone walls.[8] On Lyme’s Lord Hill and Bill Hill, Henry Pierson (1829–1919), known for his “very powerful physique” and “beautiful white beard down to his waist,” constructed walls along the roadways, using carefully fitted stones.[9] Some of Lyme’s Irish immigrants were expert stone masons.[10]

Henry Pierson’s home and stone wall on Bill Hill Road, Courtesy of the Lyme Public Hall Association, Inc.

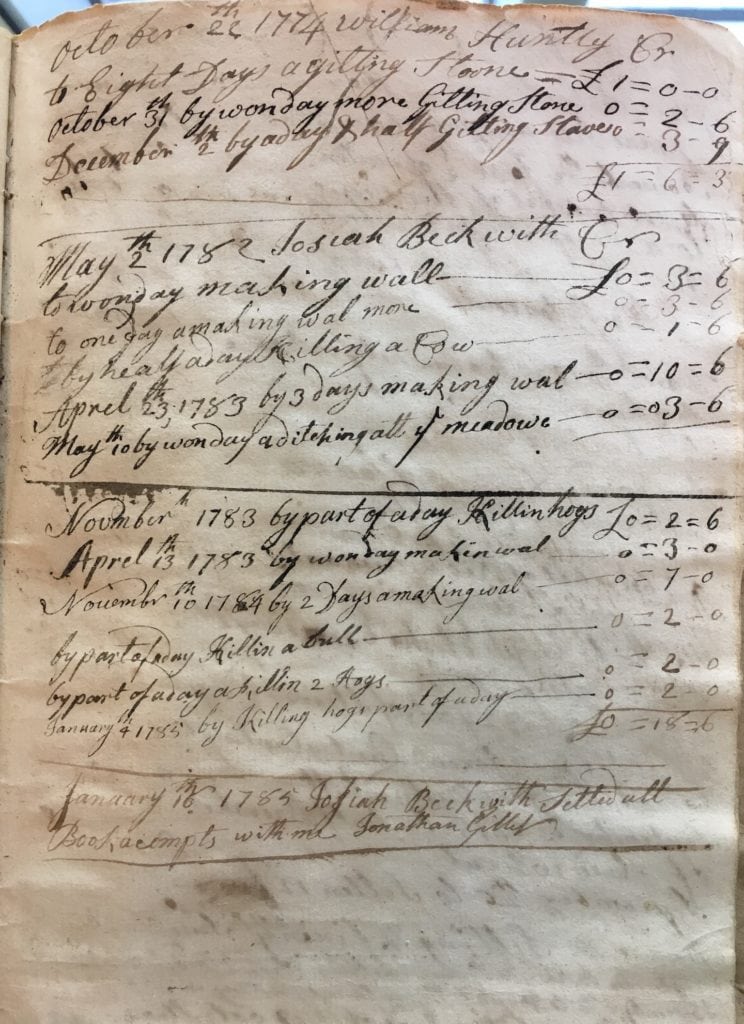

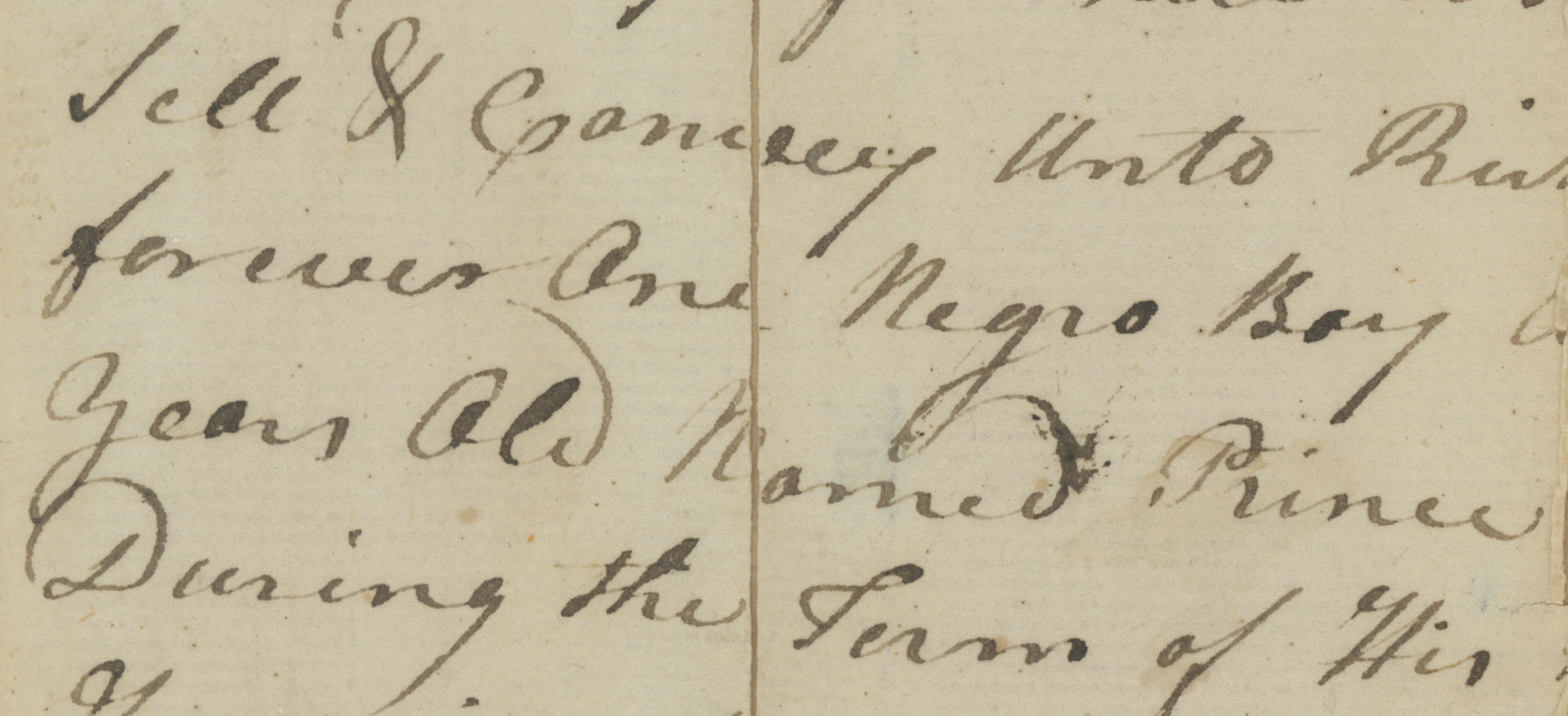

Lyme merchants exchanged goods for services, and stone wall construction was one way buyers worked off their debts. In May 1782 when Josiah Beckwith bought hay, beans, an ax, and bullets from storekeeper Jonathan Gillet,[11] Beckwith paid for his supplies by butchering hogs and cattle, digging ditches, and building stone walls, with Gillet crediting Beckwith for his “wonday making wall” and “one day amaking wal more.”[12]

Jonathan Gillet Account Book, page 28, LHSA at FGM

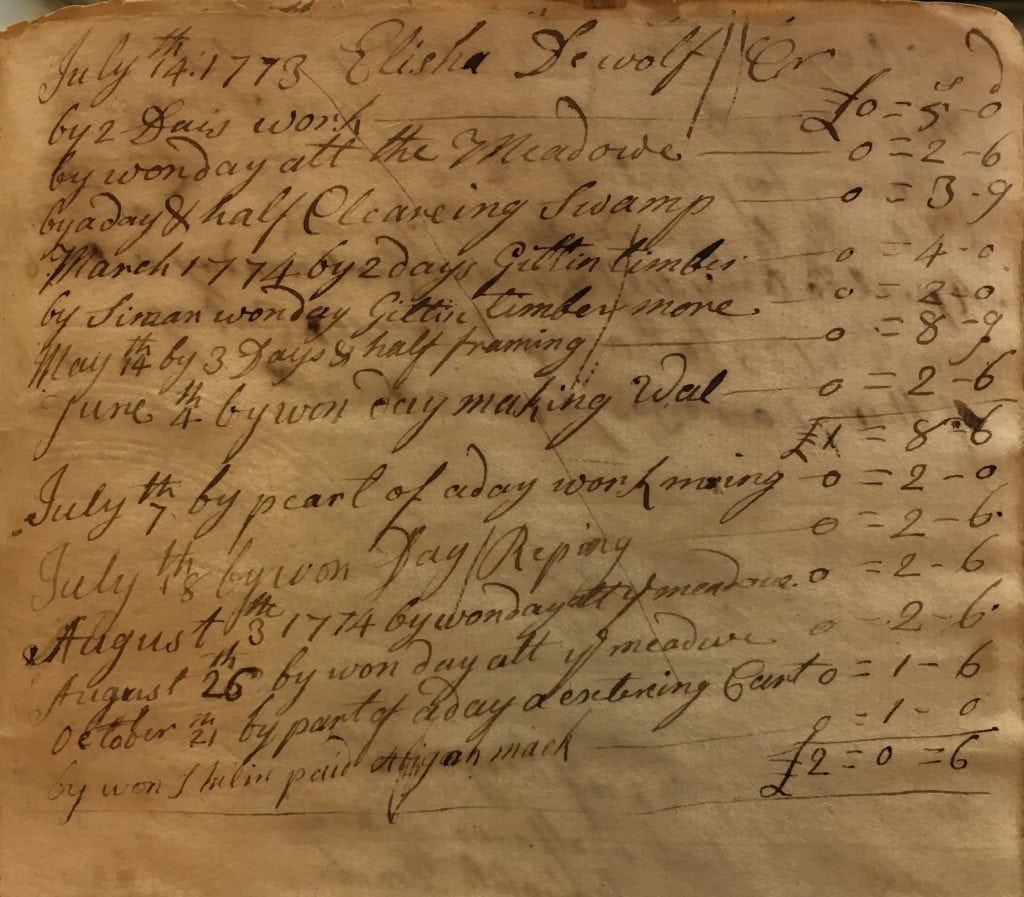

Jonathan Gillet Account Book, page 27, LHSA at FGM

Other merchants who accepted help building stone walls in exchange for goods included Elisabeth Marvin in 1813[13] and Samuel Coult in 1862.[14]

A few local landowners might have used slaves to help build walls. However, the historical record does not support reports that well over 100 slaves worked on a 13,000-acre “plantation” in Lyme (with a portion extending into Colchester and New London). Samuel Browne did acquire about 9,600 acres in this area between 1718 and 1729, land on which miles of stone walls were constructed. However, Browne or his descendants likely owned only about a dozen slaves, including women and children, and most of the Browne estate was rented to tenants who were required to improve the land themselves.[15]

It took an immense amount of labor to dig and sometimes split stones, move them to the edges of fields either by hand or with the help of oxen, and build New England’s tens of thousands of miles of stone walls. One scholar calculated that 40 million days of manual labor would have been needed to build his estimated 240,000 miles of New England stone walls, with an even greater effort required to move stones to the edges of fields. Still, assuming that a third of the New England population was “young and strong enough to move stone … each would have been responsible for building 248 feet of stone wall, scarcely a few weeks’ effort during a lifetime.”[16]

It was somewhat easier to build and mend stone walls in northern Lyme than in southern parts of the town, including present-day Old Lyme. In the north, outcrops of gneiss yielded flat slabs of stone, two to twelve inches thick.[17] Walls built with these slabs were considerably more stable than the familiar single walls made with round glacial boulders and stones, seen today in Old Lyme and throughout most of New England.

Over the past two centuries, the percentage of the Connecticut population engaged in farming, and the amount of open space land, have declined dramatically. By the mid-nineteenth century, many Connecticut farmers had abandoned their land or converted it to other uses, as they sought work in cities and mill towns or migrated west to cultivate flatter and less rocky acreage. When artists boarded at Florence Griswold’s home in the early twentieth century, however, they still saw more open countryside than we find today. Now, the old stone walls visible on woodland hikes remind us that once-open fields have been reforested.[18]

Coult farm, looking east from Tantummaheag, ca. 1890. LHSA at FGM

Most stone walls originally functioned “as linear landfills, built to hold nonbiodegradable agricultural refuse.”[19] In the mid-nineteenth century, commentators regarded stone walls as a “scourge” and “eyesore” that “disfigure[d] the land” and “mar[red] the beauty of the landscape.”[20]

Impressionist artists, however, often treated stone walls as aesthetic features that complemented the landscape. Paintings featuring stone walls evoked an ethic of hard work, independence, and an agrarian lifestyle, reminding their viewers of a seemingly simpler world lost in the congestion of city life.

Frank Vincent DuMond, Top of the Hill, ca. 1906. Oil on canvas. FGM, 1980.1

Wilson Henry Irvine, The Broken Wall, ca. 1926. Oil on canvas. FGM, Gift of George M. Yeager, 2010.3

[1] Thanks to Carolyn Bacdayan, Amy Kurtz Lansing, and Carolyn Wakeman for their help with this article. For an excellent account of the geologic processes that formed stones, and the factors that exposed them once the forest cover was removed, see Robert M. Thorson, Stone by Stone: The Magnificent History in New England’s Stone Walls [New York: Walker & Co., 2002].

[2] Although early property deeds in Lyme frequently referred to boundaries in terms of a road, a river, or land of neighboring owners, some mentioned stone walls. E.g., Deed of sale of four acres from Elisha Way to Abraham Avery [November 12, 1827], LHS (referring to the “corner of the stone wall”); Deed of sale of seven acres from William Noyes, Jr. to Richard Noyes and Joseph Noyes [December 17, 1821], Vol. 26, Lyme Land Records, p. 498 (referring to “a new wall”).

[3] Susan Allport, Sermons in Stone: The Stone Walls of New England and New York [Woodstock, VT: The Countryman Press, 2012], p. 143; Thorson, op cit., p. 158.

[4] Colonial laws required farmers to fence cultivated areas to keep livestock out of their crops. E.g., The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut Prior to the Union with New Haven Colony, May 1665 [Hartford: Brown and Parsons, 1850], pp. 516-517, available at https://archive.org/details/publicrecordsofc001conn. See also Allport, op. cit., pp. 34-35; Thorson, op. cit., p. 95.

[5] Allport, op. cit., p. 89; Thorson, op. cit., pp. 102-103.

[6] According to some writers, Native Americans also built stone structures, including walls, before European settlers arrived. See, e.g., Markham Starr, Ceremonial Stonework: The Enduring Native American Presence on the Land [North Stonington, CT: Fowler Road Press, 2016]. Others have persuasively argued that many supposed Native American structures were in fact geologic formations or the work of colonists. See, e.g., “Pre-European Contact” [2010], University of Connecticut Stone Wall Initiative, https://stonewall.uconn.edu/investigation/pre-european-contact/.

[7] Diary of Joshua Hempstead of New London, Connecticut, Covering a Period of Forty-seven Years from September, 1711, to November, 1758 [New London, CT: The New London Historical Society, 1901], p. 75, available at https://archive.org/details/diaryofjoshuahem00hemp.

[8] See ibid. pp. 156, 579, 607, 626, 702.

[9] James Ely Harding, Lyme as It Was and Is [published by author, 1975], p. 40.

[10] Harding referred to the work of Italian immigrants along highways, ibid., but Lyme historian Carolyn Bacdayan believes it more likely that Irish immigrants worked on stone walls locally. Author conversation with Carolyn Bacdayan, June 13, 2018. For discussion of the work of Irish and Italian stone masons in the northeast, see Allport, op. cit., pp. 161-169.

[11] Gillet also served as a captain in the Revolutionary War. See “Documents: Tracing Capt. Jonathan Gillet (1720–1786)”.

[12] Jonathan Gillet, Account Book [1771], LHS, p. 28. In 1774, Elisha Dewolf also worked off his debt to Gillet by “making Wal.” Ibid. p. 27. It was common for writers in Gillet’s day to spell and capitalize inconsistently. Standardized spelling developed gradually, as dictionaries gained popularity during the 1800s.

[13] During 1809–1813, Marvin sold John Gilbert cheese, corn, trousers, “overhalls,” and the right to use Marvin’s saw mill and cider mill. Gilbert paid his debt by undertaking various chores, including, on December 7, 1813, “making wall.” Elisabeth Marvin, Account Book [Sept. 1806], LHS, p. 21. A day later, Marvin credited Samuel Chadwick for working on a wall, to help pay for a “meet cask” he had purchased. Ibid. pp. 36-37.

[14] On May 31, 1862 William Coult credited Charles J. Beckwith “[b]y 5 days making wall at 92 cts. $4.60.” William Coult, Account Book, LHS, p. 13. See also ibid. p. 21 (crediting Gurdon Clark $5.88 for “making wall”).

[15] Historian Bruce Stark explored the sources of the doubtful accounts that Browne owned 13,000 acres and a large number of slaves, researched information about the slaves owned by Browne or his descendants, and documented the roles of tenants in clearing and improving the Browne land. Bruce P. Stark, “The Myth and Reality of Slavery in Salem, Connecticut,” Connecticut History, Vol. 50, No. 2 [Fall 2011], p. 158.

[16] Thorson, op cit., p. 142. See also Allport, op. cit., p. 18. Thorson’s estimate of 240,000 miles of stone walls, see Thorson, op. cit., pp. 1, 141-142, may include walls in rural New York, in light of information in Thorson’s cited reference, Oliver Bowles, The Stone Industries [New York and London: The McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 2d ed. 1939], pp. 297-298, available at https://archive.org/details/stoneindustriesd00bowl.

[17] Harding described outcrops of gneiss north of Beaver Brook Road, which intersects the northern end of Grassy Hill Road. James E. Harding, Lyme Yesterdays [Stonington, CT: Pequot Press, Inc., 1967], p. 50. The outcrops extend into Hadlyme.

[18] In 1825, only 25 percent of Connecticut was forested; by the twenty-first century, 60 percent was woodland. Eric H. Wharton et al., The Forests of Connecticut [U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Resource Bulletin NE-160, 2004], pp. 2, 5. In 1900, an estimated 38 percent of Connecticut was covered by forest, and by 1910 that coverage had increased to 41 percent. “Long Island Sound Study: Changes in Forest Cover in CT and NY” [2012], http://longislandsoundstudy.net/2012/06/changes-in-forest-cover-in-ct-ny/.