Featured image: Griswold House table set with Fitzhugh china

Every holiday season when place settings with the green Fitzhugh pattern appear on the table in the Florence Griswold Museum’s historic dining room, questions arise about the origins of the distinctive porcelain. Visitors often assume that the place settings with the initial “G” painted gracefully on each piece belonged to Florence Griswold’s parents. Instead the elegant china followed a different pathway to Lyme.

The Fitzhugh pattern decorated Chinese export ware for only a few decades, from the 1780s through the 1820s. Its characteristic design, suggestive of Chinese textile motifs and produced mostly in blue and white, features four groups of plants or flowers arranged around a central medallion. Named for Thomas Fitzhugh, who helped open China and Macao to foreign trade as an agent of the British East India Company, the pattern was less frequently produced in green and other colors. Fitzhugh place settings were made and glazed in the recently restored imperial kilns at Jingdezhen, a hilly town in southern China near the country’s largest porcelain deposits. From there they traveled 400 miles south to busy workshops in Canton to be decorated by skilled enamellers. Wealthy buyers in the west commissioned sets with monograms, coats of arms, or patriotic symbols like the American eagle in the central panel.[1]

Fitzhugh plate. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Griswold Terry Atkins

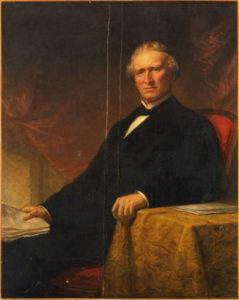

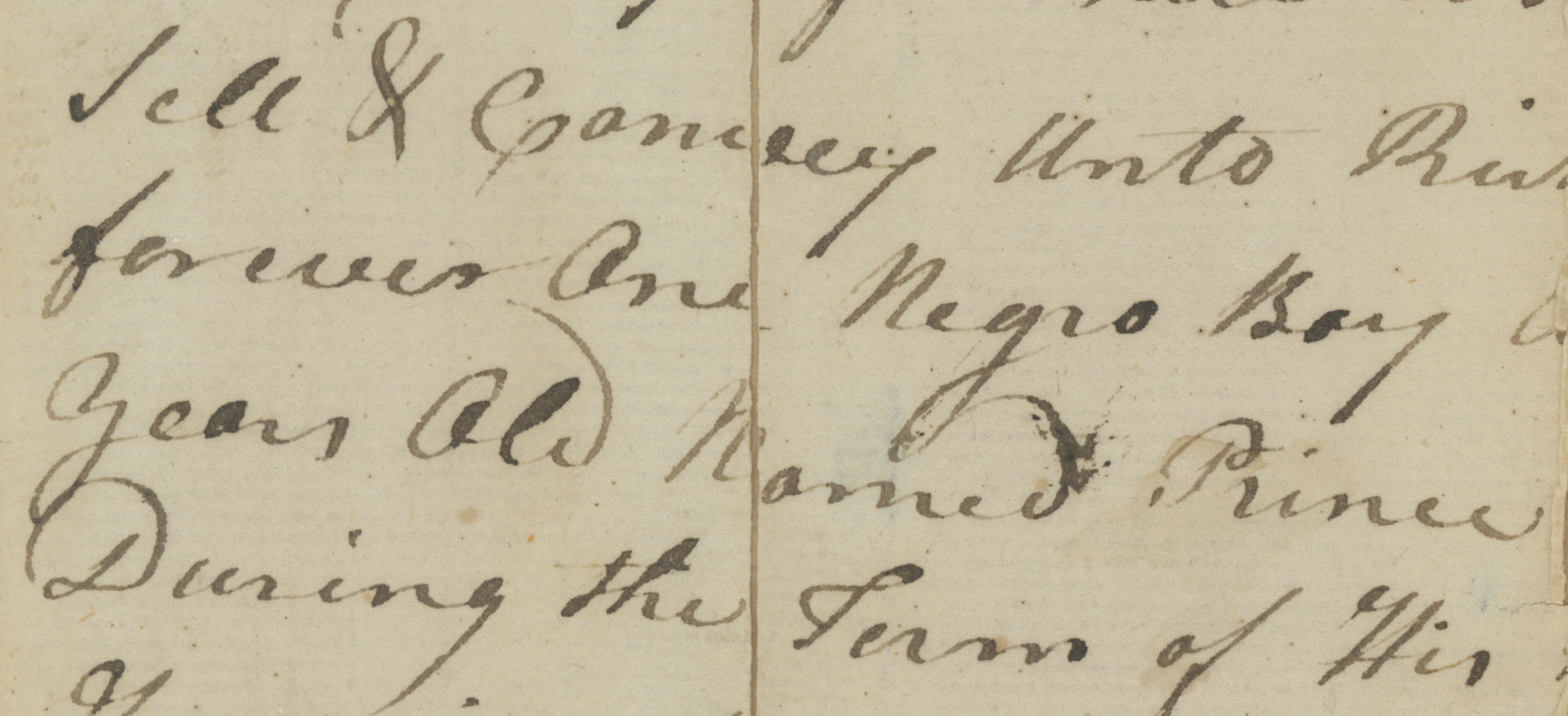

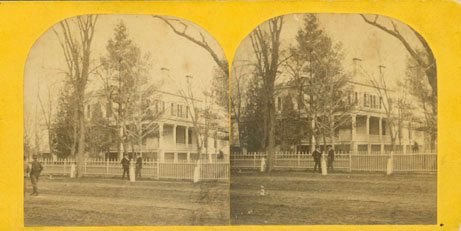

The Fitzhugh place settings on display at the Florence Griswold Museum reached Lyme through Richard Sill Griswold (1809-1849), who in 1841 built a stately home, later called Boxwood, for his second wife on land provided by his father-in-law James Mather (1785-1842). According to a Yale biography, Mr. Griswold, born in New York City, traveled to China as a representative of his father’s merchant house soon after his Yale graduation in 1829.[2] The firm N.L. & G. Griswold, which Richard’s father George Griswold (1777-1859) and his uncle Nathaniel Lynde Griswold (1773-1847) from East Lyme started in about 1796, began as a flour store at 69 Front Street. Records of the firm have not been discovered, but a survey of New York’s 19th-century merchant houses notes that by 1804 when the firm relocated to 86 South Street, the Griswold brothers were shipping flour heavily to the West Indies and importing large quantities of rum and sugar.[3]

N.L. & G. Flag

George Griswold had already started his journey to wealth and recognition when he married in 1800, at age 23, Elizabeth Woodhull (1784-1810), raised in a prominent New Jersey family and said to be “a royal descendant of William the Conqueror.” When she died in 1810, less than a year after the birth of their fifth child Richard Sill Griswold, her husband served as a director of the Columbia Insurance Company, and in 1812 he became a director of the profitable Bank of America.[4] Two years later he married as his second wife Maria Cumming (1792-1880) of Newark, and by age eleven Richard Griswold, his father’s oldest surviving son, had four half-siblings.

John Frazee, George Griswold, ca. 1842. Marble. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of the Hon. Mr. John Davis Lodge

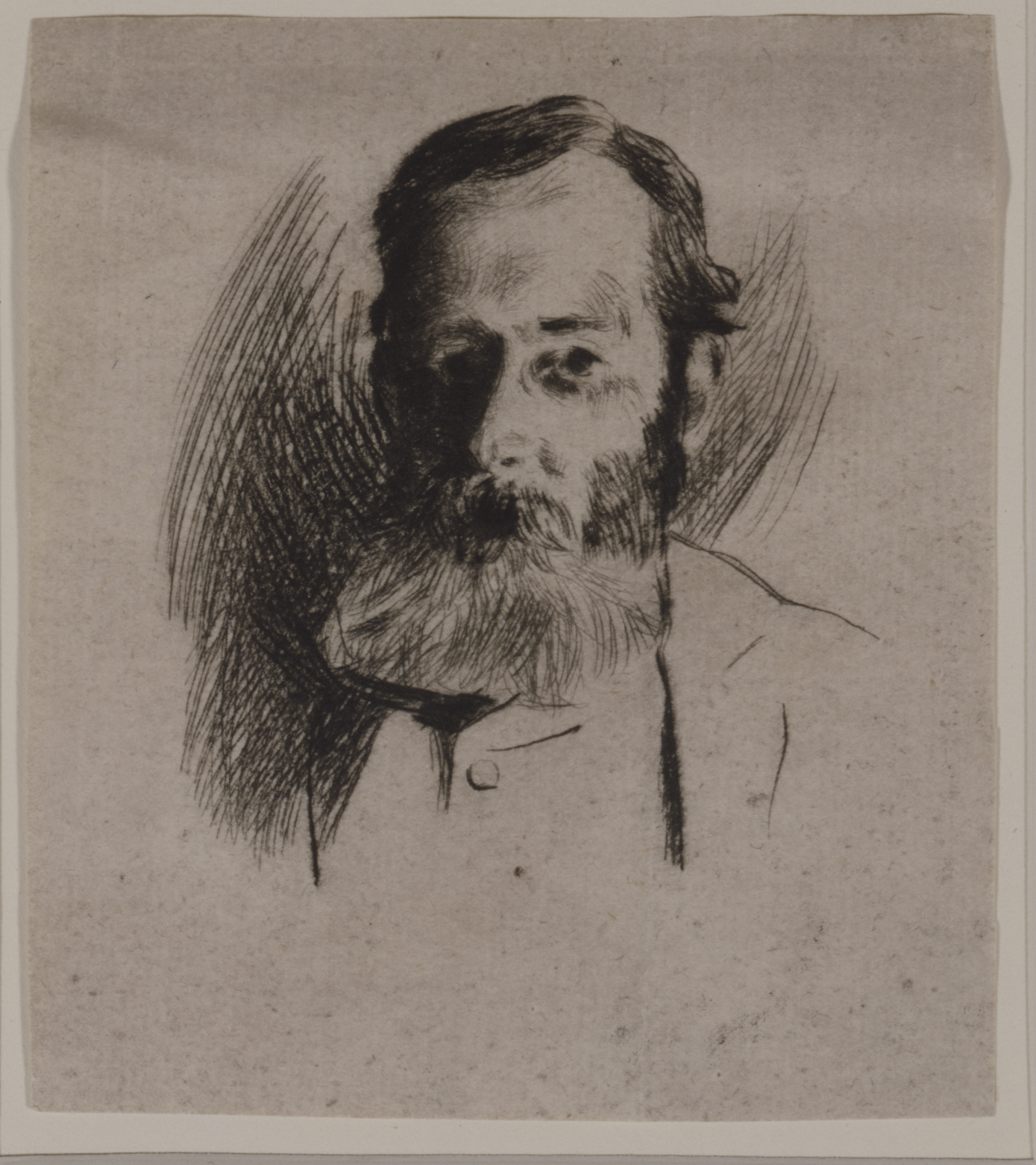

The date of Nathaniel and George Griswold’s entry into the China trade is not known.[5] According to the Providence Gazette, eleven American vessels were fitted out in 1783 for voyages to China and India, and the Empress of China, the first clipper ship with American registry to reach Canton, arrived the following year. Along the bank of the Pearl River, foreign merchants conducted business with officially sanctioned Chinese counterparts in thirteen designated “factories” that provided warehouse space on the lower floors and living quarters above.[6] John C. Green (1800-1875), whom the N.L. & G. Griswold firm hired initially as a clerk in 1816, would likely have been based there between voyages as he conducted the Griswold brothers’ China business for more than a decade. While serving as supercargo of the first of four ships named Panama that N.L. & G. Griswold commissioned, John Green negotiated in 1829 one of the earliest arrangements by which American merchants paid for Chinese goods in British pounds rather than Spanish dollars.[7]

Unknown Chinese artist, The thirteen Canton factories, painted on glass, ca. 1805, showing an American flag

Daniel Huntington, John Cleve Green, 1870. Princeton University Art Museum

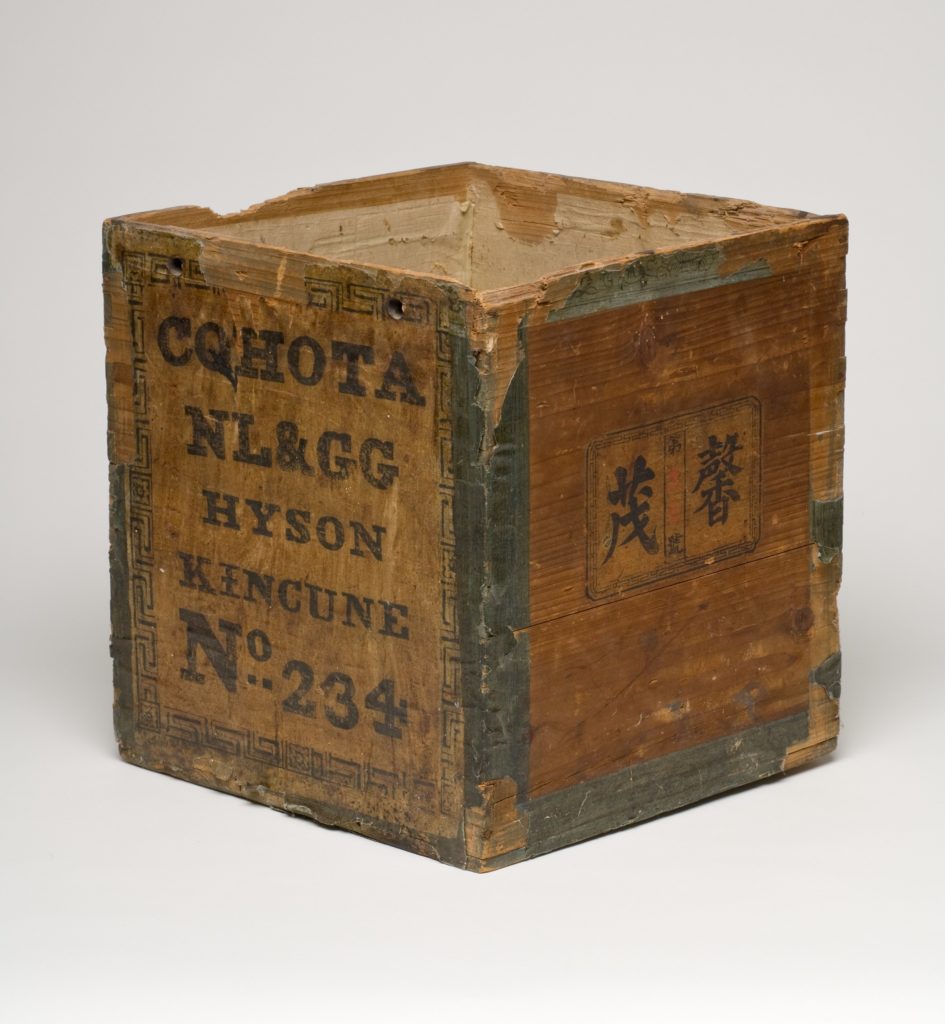

Inventories for N. L. & G vessels have not been found, but the firm is said to have “imported many Canton cargoes.”[8] Heavy crates of Chinese porcelain served as ship’s ballast, providing a platform on which boxes of perishable teas and silks avoided damage from leaking bilge water. Sturdy wooden boxes bearing the name of the shipping company protected the fragile tea leaves. In 1833 a promotional notice in New York’s Evening Post declared that great care was taken “by Mr. John C. Greene” with cargo “warranted to be new teas, country packed.”[9]

Unidentified Maker, N.L.G.G. Tea Box used on the ship Cohota, ca. 1844. Wood, paper. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. David J. Powell

By the time Richard Griswold reached China in 1829 as his father’s agent, unmarried and newly graduated from Yale, Fitzhugh-patterned settings, according to most sources, were no longer being produced.[10] His father most likely had ordered the elegantly decorated dishes with the initial “G” at least a decade earlier, either for his first wife Elizabeth before her death in 1810 or for his second wife Maria with whom he raised his growing family in a fashionable New York townhouse at 9 Washington Square. After Richard returned from China in 1833, he became a partner in his father’s company, and two years later he married in Lyme Louisa Griswold Mather (1815-1840), granddaughter of the town’s most prosperous merchant Samuel Mather, Jr. (1745-1809). Five years later in 1840 Louise died in Brooklyn with an infant son, and in 1841 Richard married her younger sister Frances Mather (1822-1889), for whom he built a spacious Lyme home. We can speculate that the elegant set of Fitzhugh china passed to Richard as George Griswold’s eldest son either when he married Louisa in 1835 or after he settled in his brick mansion house, next door to the Mather family home, with her sister Frances.

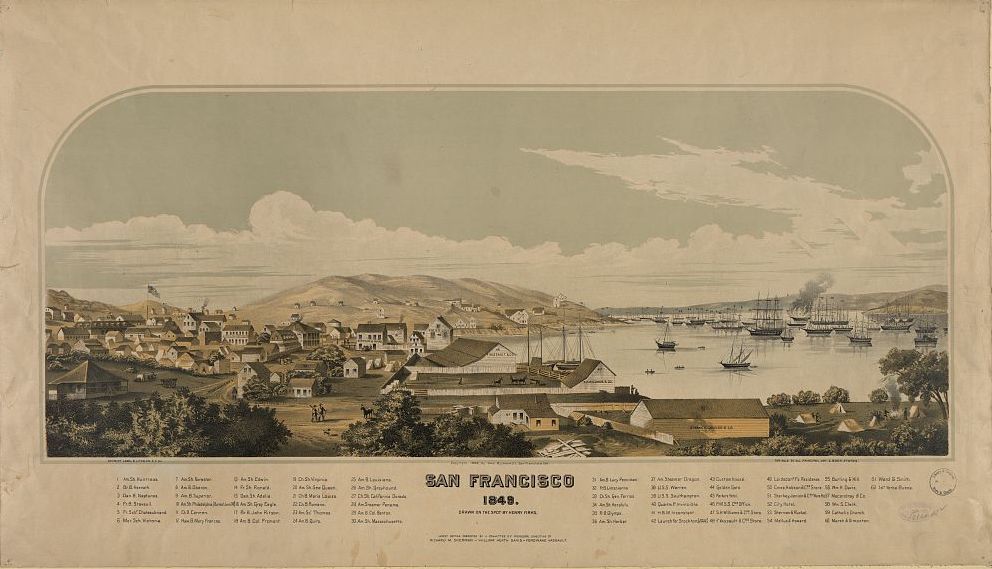

We catch glimpses of Richard Griswold and his new wife Frances Mather in letters that Florence Griswold’s mother sent in 1841 to her husband Robert Harper Griswold (1806-1882), master of the trans-Atlantic packet ship Toronto. The letters conveyed local news and occasionally mentioned, with a note of envy and remonstrance, his attentive and successful younger cousin. “Mrs. Richard Griswold was here yesterday,” Helen Powers Griswold (1820-1899) wrote to her husband at sea on August 13, 1841. “I have no doubt but she has an excellent, kind, indulgent husband, he must be very fond of her, he does not leave her but a few days at a time and takes her down with him every other week.” In a letter written three days later she remarked that Richard Griswold intended his new house to be “much more elegant, than anything that has, or ever will be built in Lyme, it is to be of Brick and completed in December, all the workmen are from N.York.[11]

Boxwood before additions. Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

A century and a half later a deed of gift to the Lyme Historical Society in 1985 describes a “55-piece set of Fitzhugh Chinese-export porcelain, each piece initialed “G” (Griswold).” The appraisal summary lists 14 8-inch plates, 16 6½-inch plates, 7 teacups and saucers, and 5 coffee cups, noting that “All pieces in perfect condition.” The gift of Fitzhugh porcelain also notably included a teapot, three covered dishes, and two large platters. On each piece the letter “G” in gold appears in the center medallion surrounded by four chrysanthemum sprays. Entwined in the blossoms are emblems of a Chinese scholar’s traditional mastery of painting, music, calligraphy, and accounting. The intricate border design weaves butterfly images together with latticework, stylized geometric motifs, and a dense honeycomb pattern.[12]

Fitzhugh china, Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Griswold Terry Atkins

From Frances Mather Griswold, Richard Sill Griswold’s widow, the Fitzhugh china passed to their daughter Frances Griswold Terry and ended up in the Pennsylvania home of Griswold Terry Atkins, a great-grandson. A letter to the museum’s curator in 1985 from donors Griswold Atkins and his wife Ethel Atkins states: “We will miss our baby but are very happy that it has found such a good home to end its many hazardous years of travel from one china closet to another.”[13]

[1] Craig Clunas, ed., Chinese Export Art and Design (Victoria and Albert Museum, 1987), p. 60; Jan-Erik Nilsson, “Chinese Export Porcelain for the West.”

http://www.gotheborg.com/~gothebor/qa/exportforthewest.shtml

[2] Franklin Bowditch Dexter, Biographical Notices of Graduates of Yale College (New Haven, 1913), p. 199.

[3] Walter Barrett, The Old Merchants of New York (New York, 1885), p. 158; Richard Cornelius McKay, South Street: A Maritime History of New York (New York, 1934), p. 92 ff.

[4] Portrait Gallery of the Chamber of Commerce of the City of New York (1890), p. 133.

[5] Barrett, p. 158, states: “I do not know what year this house went into the “China trade.”

[6] Providence Gazette, August 7, 1787, cited in Christina H. Nelson, Directly from China: Export Goods for the American Market, 1784-1930 (Peabody Museum of Salem, 1985), p. 11; Herbert, Peter and Nancy Schiffer, Chinese Export Porcelain: Standard Patterns and Forms, 1780-1880 (Exton, PA, 1975), pp. 11-12; Jean McClure Mudge, Chinese Porcelain for the American Trade, 1785-1835 (Wilmington, 1981), p. 116.

[7] Barrett, pp. 31-32; Henry Hall, ed., America’s Successful Men of Affairs: The City of New York (New York, 1895), p. 279; “The Clipper Ship Challenge,” in Pacific Maritime Review (Vol. 19, 1922), p. 408; Walter Hubbell, History of the Hubbell Family (New York, 1881), p. 133; Five Colleges and Historic Deerfield Collections Database.

http://museums.fivecolleges.edu/detail.php?museum=&t=objects&type=exact&f=&s=piu&record=10

[8] Mudge, p. 115.

[9] Schiffer, p. 11; for New York Evening Post, see:

[10] Nelson includes in her study of Chinese export goods five examples of the Fitzhugh pattern and dates the dish that most closely resembles the Griswold china ca. 1815-25. Nelson, p. 80.

[11] Helen Powers Griswold to Robert Harper Griswold, August 13, 1841, August 18, 1841. LHSA.

[12] Letter of appraisal, LHSA. For Fitzhugh design motifs, see Schiffer, p. 37; Mudge, pp. 164-166.

[13] Griswold Terry Atkins to Deborah Filos, 1985, LHSA.