Exhibition Notes

Exhibition Note: Lyme Artists and the Changing Landscape at Ferry Point

ON January 29, 2016

by Carolyn Wakeman

Featured image (above): Ellen Noyes Chadwick, View of Ferry Point, ca. 1860. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Krieble, Florence Griswold Museum.

Ellen Noyes Chadwick’s (1824-1900) expansive View of Ferry Point, included in the Florence Griswold Museum’s fall 2015 exhibition The Artist in the Connecticut Landscape, offers a unique glimpse of Lyme’s maritime past. Today the hotel and warehouses that clustered near the ferry wharf during the artist’s lifetime have disappeared along with the homes, windmills, and shad nets. By the time artists from New York arrived at the railroad depot on Ferry Point in the 1870s, the land dominant form displayed in her painting had already been transformed.

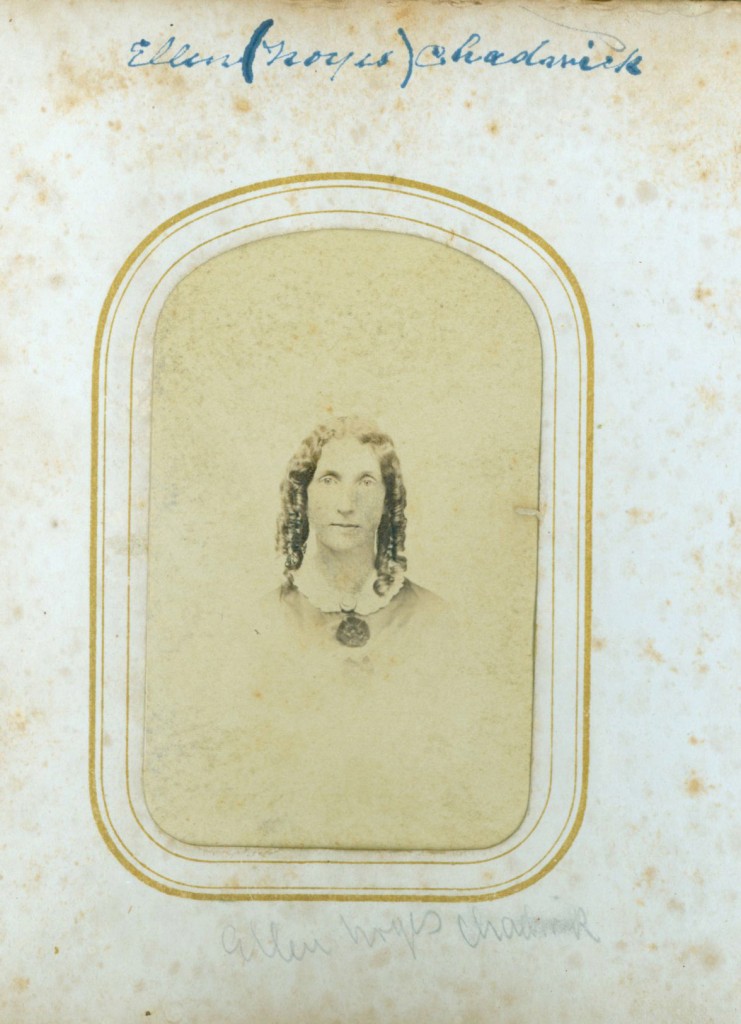

Ellen Noyes Chadwick

Ellen Noyes Chadwick, a descendant of Lyme’s first minister Moses Noyes (1643-1729) and a talented local artist, grew up in a comfortable home on a rise overlooking the mouth of the Connecticut River. Built for her father Enoch Noyes (1789-1877) in 1820 at the time of his marriage to Clarissa Dutton (1798-1838), the family dwelling stood along the road laid out in 1755 to connect the stagecoach highway through Lyme with the ferry landing. A great English elm with branches spreading 150 feet shaded her front dooryard, and a stone marker at the east end of her garden, placed by Benjamin Franklin’s assistants, measured the distance to the New London ferry as 16 miles.[1]

Shad nets at Ferry Point, showing Enoch Noyes house and Reuben Champion house, ca. 1885. LHSA.

Mile marker, Ferry Road, 1755. LHSA.

The eldest of five children, Ellen attended the first district school on Lyme’s main street until age fifteen. As a young woman, along with her neighbor Susan Champion (1820-1911), she studied painting in the village with her aunt Phoebe Griffin Noyes (1797-1875), a New York-trained portrait miniaturist who nurtured the artistic talent of local pupils in a small private home school over four decades. When Mrs. Noyes, a full-time teacher and mother of five, found time to paint, her children served as her primary subjects, but a group portrait from about 1845 displays her appreciation for landscape details. “No pupils passed through her hands without receiving instruction in art to a point far beyond what has been usual in any school, even of later times,” an obituary tribute to Mrs. Noyes observed half a century later.[2]

Phoebe Griffin Noyes home and school, renovated by Charles H. Ludington, ca. 1890. Courtesy First Congregational Church of Old Lyme.

Phoebe Griffin Noyes, Portrait of Her Children, ca. 1845. Photocopy courtesy Ludington Family Collection.

Ellen Noyes Chadwick. Courtesy Werneth Noyes collection.

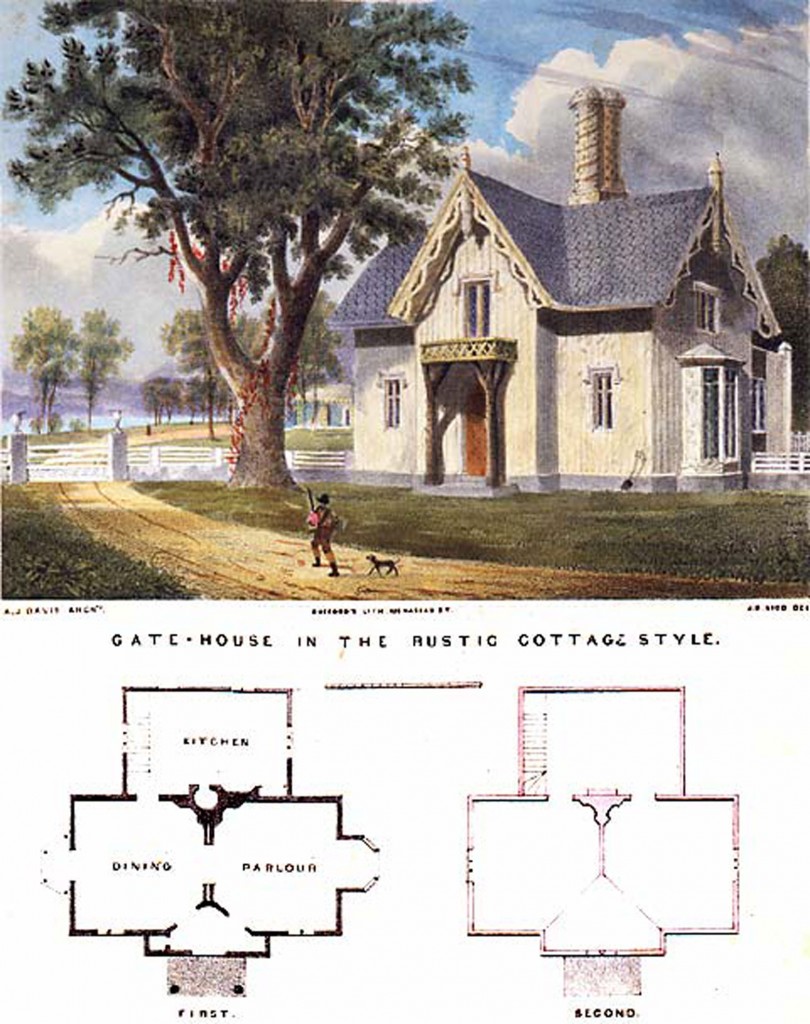

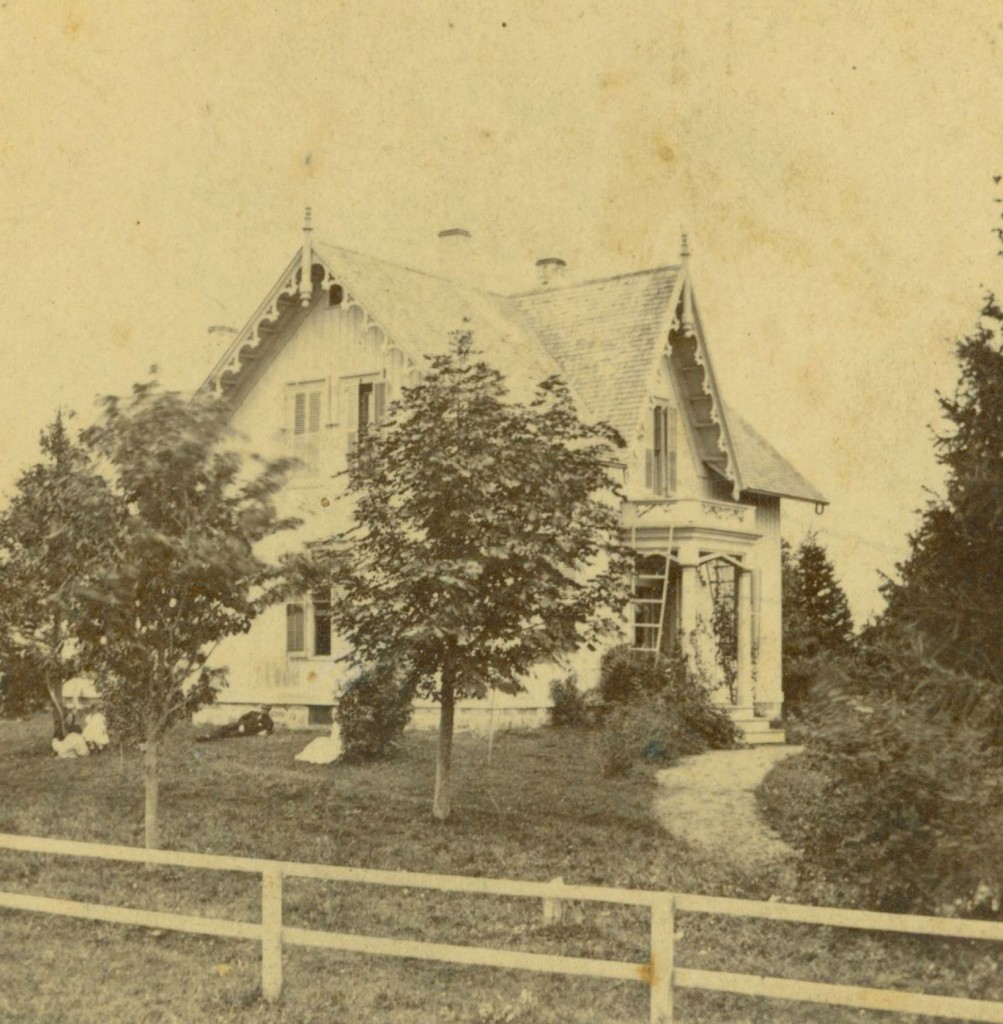

In 1848 Ellen Noyes, age 24, married the handsome young lawyer Daniel Chadwick, Jr. (1825-1884), a recent Yale graduate with a stately home in the village whom she had known from childhood. As a wedding gift her father provided a parcel of land down the hill from the family dwelling, and her father-in-law, the renowned trans-Atlantic packet ship captain Daniel Chadwick (1795-1855), built the young couple a newly fashionable Gothic revival-style cottage. Based on a design by Alexander Jackson Davis (1803-1892), the Chadwick home was the second in Lyme to depart from the colonial tradition of the older dwellings. In an undated painting Mrs. Chadwick captured the romantic aura of her cottage after a snowfall, delineating with fine brush strokes its tall gables, steeply pitched roof, and decorative moldings.[3]

Alexander Jackson Davis, Gate-house in the Rustic Cottage Style, from Rural Residences (1837).

Daniel and Ellen Noyes Chadwick house, Ferry Road, ca. 1870. LHSA.

Ellen Noyes Chadwick, Winter Landscape, Florence Griswold Museum.

Picturing Ferry Point

Engaged with the affairs of her family and community, Ellen Noyes Chadwick never pursued painting as a profession, and only three of her works have been identified. View of Ferry Point, her most ambitious painting, preserves on canvas the sweeping backdrop familiar from her childhood. From her dooryard she could see the distant Saybrook lighthouse built when she was a schoolgirl in 1838, as well as the inn, storehouses, and fishing sheds that made the area near the ferry wharf a hub of activity. Her brushwork blurs the opposite Saybrook shoreline, a technique used also in her watercolor study of sailing vessels approaching the river, but she draws the landscape of Ferry Point into sharp focus.

Ellen Noyes Chadwick, Seascape, watercolor on paper, Florence Griswold Museum.

We glimpse two rolled shad nets beside a dwelling along the far riverbank. We note the blades of a windmill and the roof of an old Mather house protruding above a central granite bluff. We see the large ferry shed and several warehouses beside the wharf, some of which may have housed workers at Reuben Champion’s (1787-) Ferry Point shipyard. Below the grass-covered bluff we notice the red brick inn with four prominent chimneys that Matthew Bacon (1785-), a farmer and practitioner of Thomsonian medicine, built just south of his home and barn in 1835 on land purchased from her father. The brick allegedly arrived as ballast on a sailing vessel from England, and shipping magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877) initially partnered in operating the inn, called Bacon House, to accommodate passengers traveling on his new steamboat line between New York and Hartford.[4]

Reuben Champion house and remains of shipyard, ca. 1940. LHSA.

Bacon House, ca. 1900. LHSA.

Ferry Point looking north, showing chimneys of Bacon House, ca. 1880. LHSA.

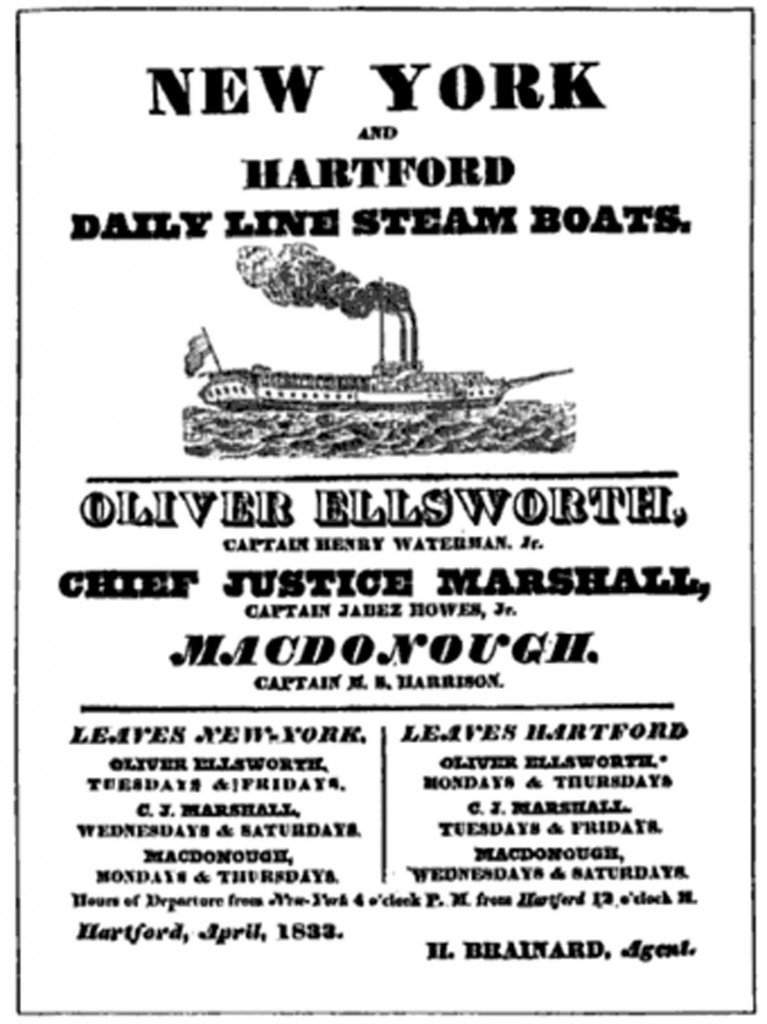

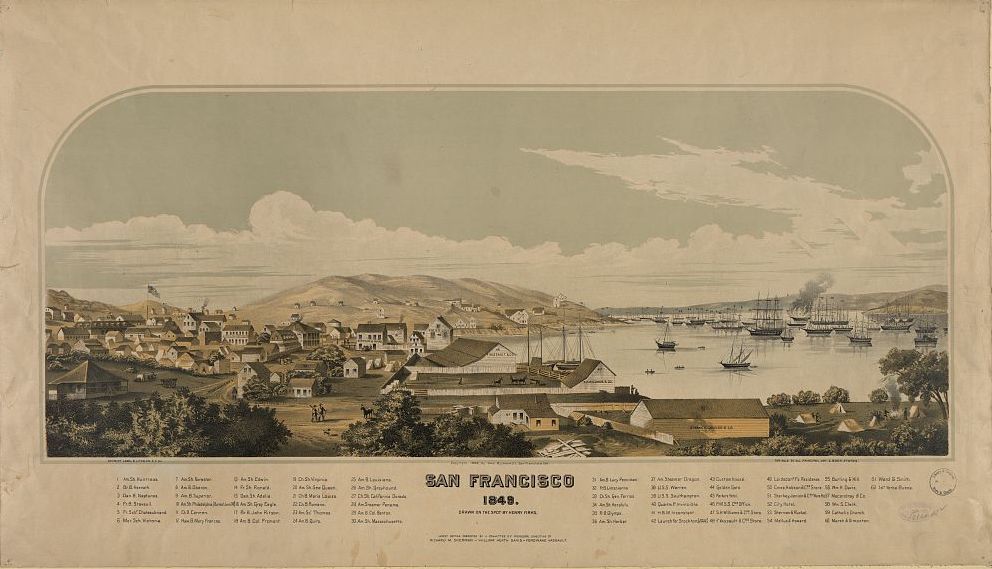

Mrs. Chadwick’s painting cannot be precisely dated, but its details document Ferry Point’s landscape before the intrusion of the railroad. Until 1852 steamboats offered travelers the fastest and most comfortable access to Lyme, and the Water Witch captained by Cornelius Vanderbilt’s brother Jacob first stopped in town when it began running as a “day-boat” to Hartford in 1833. “Her speed was a wonder for those times,” one historian noted of the Water Witch, which competed for passengers with the 60-berth Oliver Ellsworth. “She left New York at 7 A.M., and reached Hartford by sunset.”[5]

Handbill for Hartford daily steamboat line, April 1833.

Rail Service Begins

The New Haven & New London Railroad Company laid tracks through Lyme in 1851. At a town meeting in April, voters approved the railroad company’s right to lay tracks across the town road to the ferry and also to construct a “Bridge without draw” across the adjacent Lieutenant River. That summer Mrs. Chadwick’s father and more than thirty other local property owners sold to the railroad company small parcels of land along a shoreline route surveyed by Yale engineering professor Alexander C. Twining (1801-1844). Rail service started a year later, as Mrs. Chadwick’s neighbor Reuben Champion, Jr., noted in a family letter. “The Rail Road is now rapidly drawing towards completion, will be finished about middle of July. New Ferry Boat Shampushuh has arrived but don’t expect much,” he wrote to his sister Susan, adding that he had “secured the job of Ticket Agent.” A ticket from to Lyme from New Haven cost $.95.[6]

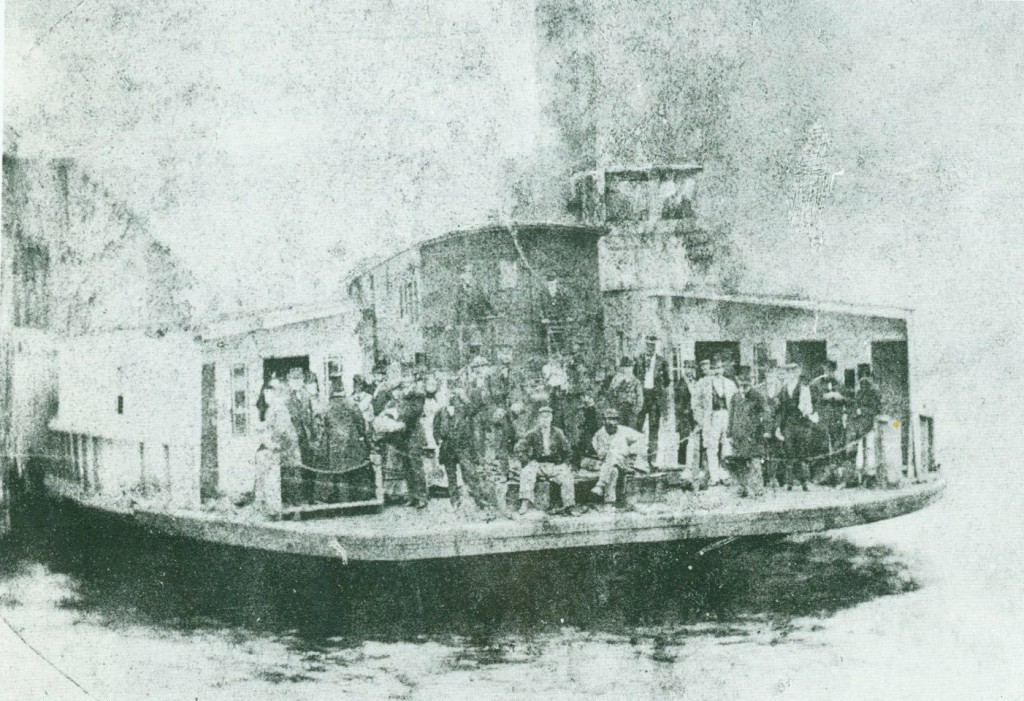

Ferry Shaumpishus carrying railroad cars and passengers, ca. 1865. Courtesy Connecticut River Museum.

Wooden railroad carriages crossed the Connecticut River on the new steam-powered train ferry Shaumpishus for the next nineteen years. But connections with the track on the opposite bank were not always smooth, as author Charles Dickens remarked when traveling from New York to Boston on a reading tour in 1867. “The steamer rises and falls with the river which the railroad don’t do,” Dickens complained, “and the train is banged uphill or banged downhill.” On his crossing a rope broke, and “the carriage rushed back with a run downhill into the boat again.” He whisked out of the carriage “in a moment,” he said, even though few seemed troubled by the mishap.

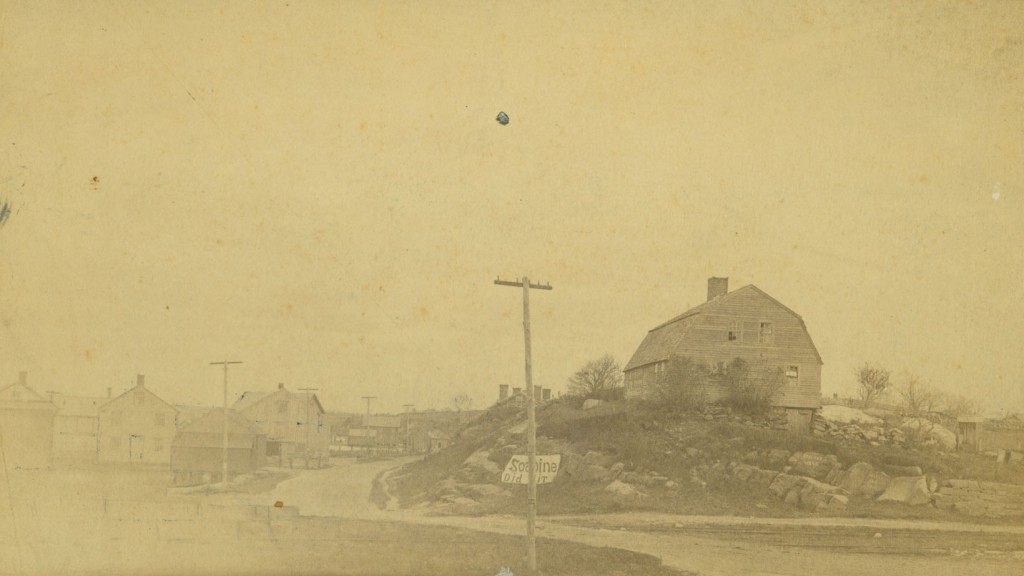

Transportation to Lyme improved after the first railroad bridge spanned the lower Connecticut River in 1870. But the Ferry Point landscape changed decisively during construction of the bridge, which was said to be made entirely of wood from Connecticut forests. Workers blasted away the rocky bluff near Matthew Bacon’s hotel to level the terrain and used the granite to build supporting piers for the railroad bridge.[7]

Train crossing after crossing Connecticut River, showing Lyme depot, ca. 1880. Courtesy Carolyn Wakeman.

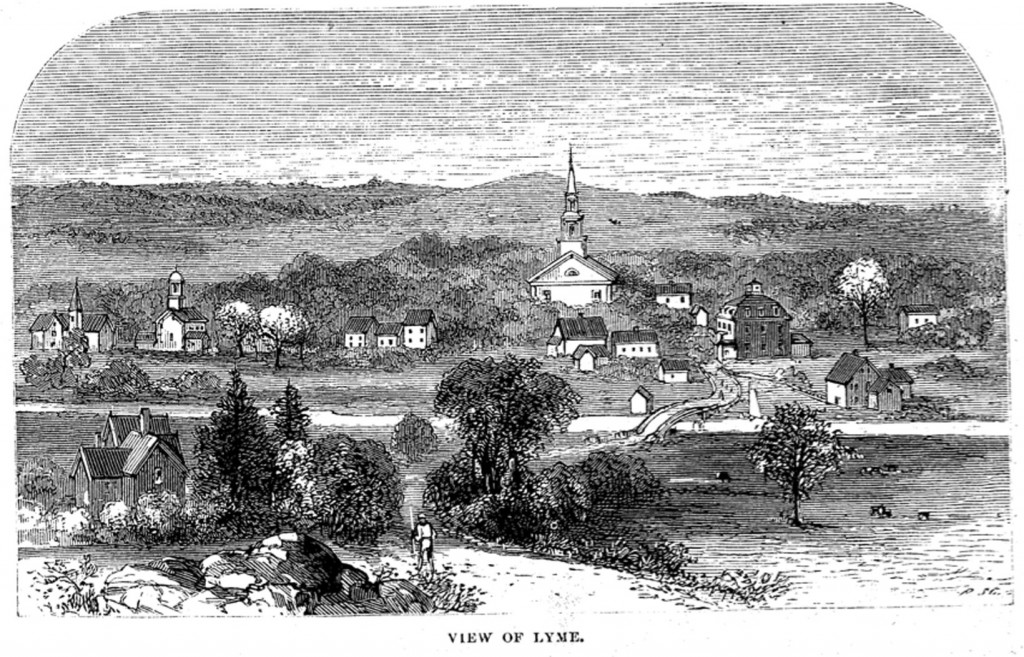

A syndicate of owners eager to encourage seasonal visitors soon opened a spacious hotel near the intersection of Ferry Road and Lyme’s elm-shaded main street. When historian Martha J. Lamb (1826-1893) arrived by train from New York in 1874, she stayed at the new Pierrepont House while drafting an extended profile of Lyme to appear in Harper’s Magazine. “From Noyes Hill, a few rods north of the station,” she wrote, referring to the site of Ellen Noyes Chadwick’s childhood home, “you obtain your first glimpse of the village, or rather of its roofs and chimneys and spires among the tree-tops.” Mrs. Lamb urged readers to stop at Lyme station and discover the town’s historic charm and scenic beauty. “The ferry road crosses a snug New England bridge, and guides you to the Pierrepont House, a new summer hotel, which occupies a commanding position just outside the wealth of shade which shields the town,” she remarked.[8]

Attributed to Charles Parsons, View of Lyme, showing home of Ellen Noyes Chadwick,

Lieutenant River bridge, and Pierrepont House. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 1876. LHSA.

Pierrepont House, ca. 1880. LHSA.

Artists in Lyme

Ellen Chadwick served as one of Mrs. Lamb’s principal informants about Lyme’s history and traditions and described in a letter the cultural pursuits that had long distinguished the town. “There is much love of art & music among the inhabitants,” Mrs. Chadwick wrote. “Some of the ladies paint in oil and water colors exceedingly well for amateurs, and there are very accomplished musicians playing the piano, harp, guitar, and violin, with great skill.” Four years later she would enroll her daughter Bertha Chadwick (1866-1940) at the home school on Lyme Street opened by Florence Griswold (1850-1937) and her sisters, where music and art were central to the curriculum.[9]

Mrs. Martha J. Lamb, ca. 1880. LHSA.

Students with musical instruments at the Griswold Home School, ca. 1885. LHSA.

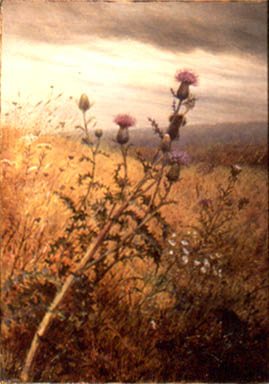

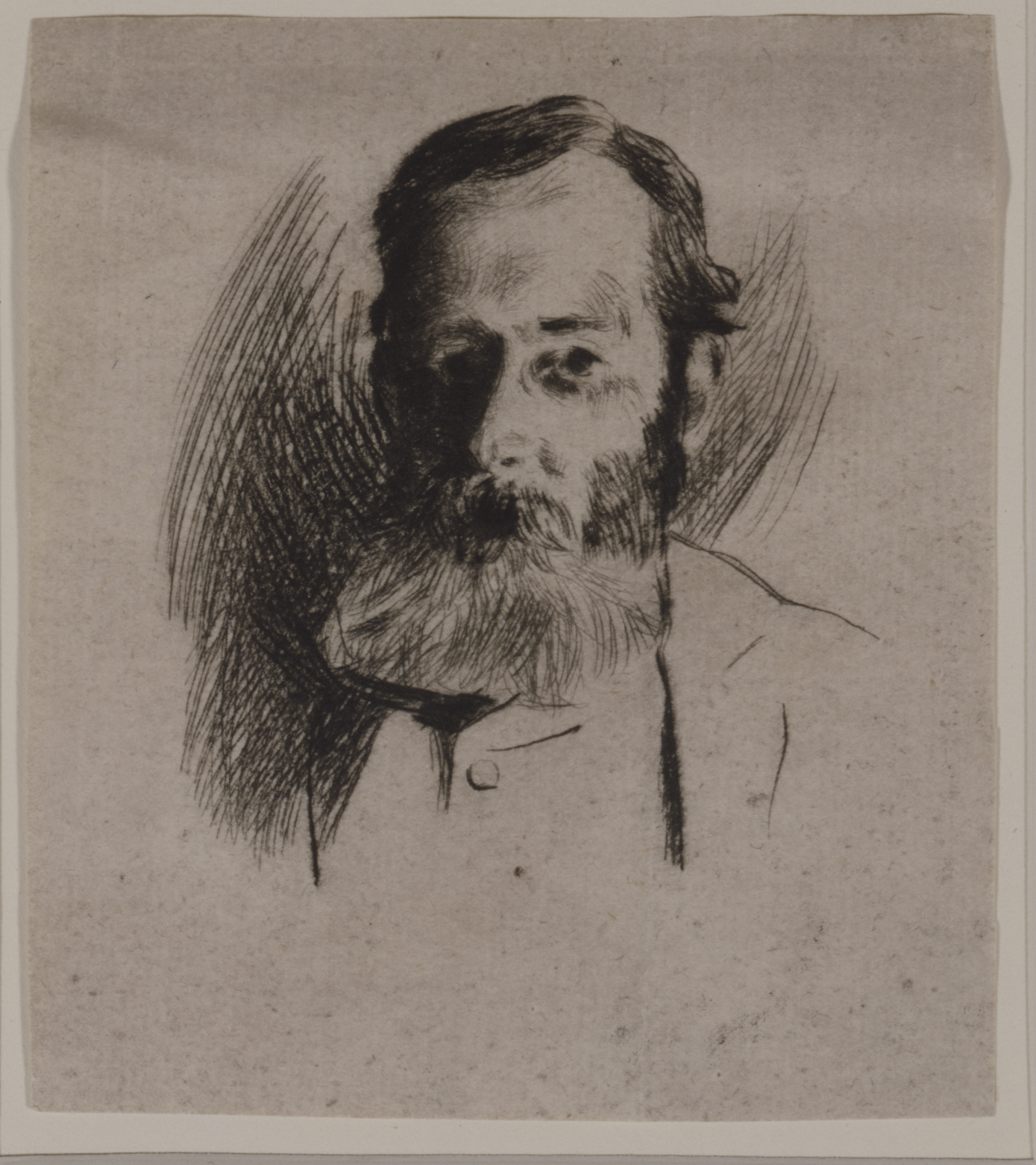

Mrs. Chadwick also noted that several New York artists had recently visited Lyme. “Artists are beginning to find the picturesque attractions of the neighborhood,” she wrote in 1874. “Mr. Bellew, & Mr. Parsons, chief artist for Harper’s, have taken sketches here, and Miss Fidelia Bridges, after spending last summer near the lakes in the center of the town, came again this year, and expects to make it a special summer resort for the prosecution of her beautiful art.”[10]

Fidelia Bridges, Thistles in a Field, 1875. Oil on canvas.

Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company.

While Mrs. Chadwick’s ongoing engagement with the arts contributed importantly to Lyme’s cultural legacy, it was her eldest son Charles Noyes Chadwick (1849-1920), a successful businessman in Brooklyn who summered on Ferry Point, who arranged in 1894 for artist Joseph H. Boston (1860-1954) to locate his summer classes for the Brooklyn School of Arts and Sciences in town. “Professor Boston with his Art school, expect to arrive at the Pierrepont to-morrow. Probably he will bring a dozen or fifteen young ladies with him,” the local Sound Breeze newspaper reported on June 19. The art students paid $6 a week for meals and lodging at the hotel on Ferry Road. Mrs. Chadwick, still active in her later years, would certainly have met Professor Boston and other artists, like Clark Voorhees, who visited Lyme before the turn of the 20th century. The young Yale graduate passed her home repeatedly on his touring bicycle in the summer of 1896 while staying at Bacon House, by then popular as a rustic inn for sportsmen.[11]

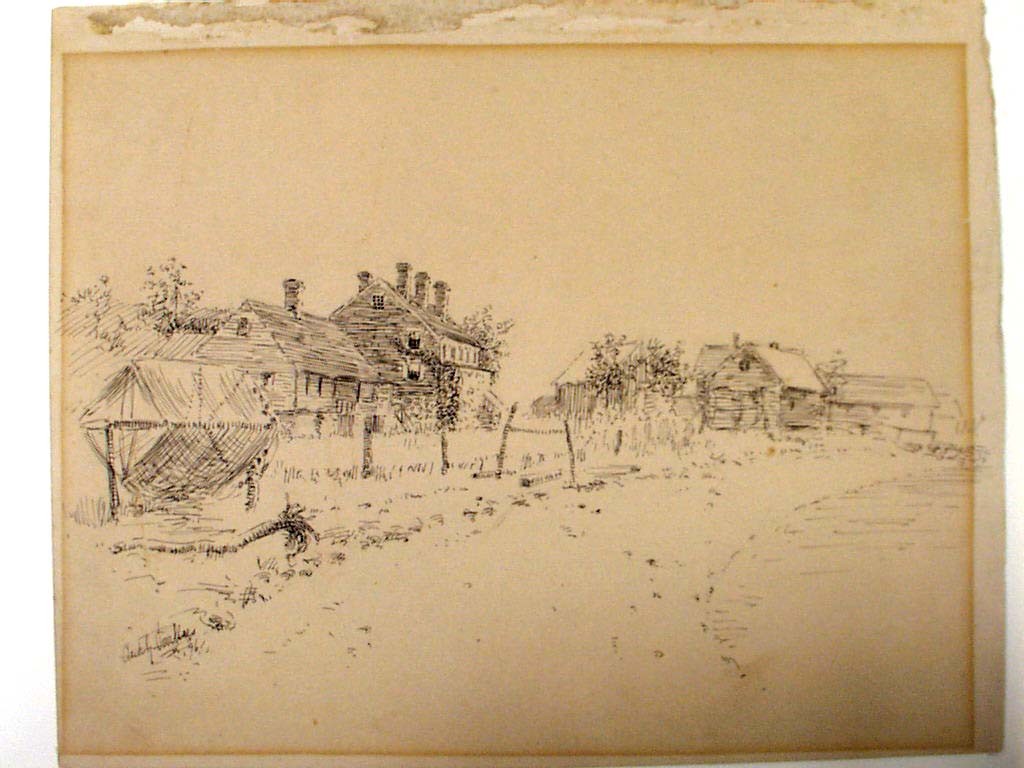

Clark Voorhees, The Bacon House, Old Lyme, 1896. Pen and ink on paper.

Florence Griswold Museum; Gift of Mrs. Wells Barney.

While Mr. Voorhees’ mother and sister rented rooms in Florence Griswold’s home, he engaged actively in the social life of the town, playing golf and tennis and singing in the church choir, accompanied by organist Bertha Chadwick. A hunting enthusiast, he often spent mornings shooting birds on the salt marshes and devoted afternoons to sketching. One of his pen and ink drawings depicts the aging hotel near the ferry wharf, and his diary also mentions sketches of the ferry, the old tap room, the Bow Bridge, and the landscape along Neck Road.[12] One of the founders of the Lyme art colony, Clark Voorhees would soon purchase an old gambrel-roofed house built some two centuries earlier beside the Connecticut River.

Clark Voorhees house, Neck Road, 1907. LHSA.

After Ellen Noyes Chadwick died at age 76 in 1900, New York artists arrived in growing numbers at the railroad depot on Ferry Point. In the years ahead they captured “the picturesque attractions of the neighborhood” with a new impressionist vision and established at Florence Griswold’s home one of the country’s most important centers of landscape painting. Meanwhile the home on Ferry Road where Mrs. Chadwick lived for more than half a century passed to her daughter Bertha, and in 1905 one prominent visitor inquired about its availability as a summer residence. “Mrs. Wilson and I have just finished a stay of some eight weeks at Lyme, Connecticut, whither we went in order that Mrs. Wilson might join the sketching class there,” Woodrow Wilson, president of Princeton University, wrote. Could he rent for the following summer, he asked, her “very attractive cottage by the bridge.”[13]

Bacon House before remodeling as Ferry Tavern, showing former home of Matthew Bacon, ca. 1924. LHSA.

[1] Special thanks to Amy Kurtz Lansing and Charlie Beal for generous assistance. See notes about Ferry Point written in 1913 by Mrs. Charles Noyes Chadwick (1846-1931). LHSA.

[2] School enumeration, Lyme first school district, August 1838, LHSA. In 1840 Ellen’s widowed father Enoch Noyes married Phoebe Griffin Noyes’ sister Catherine Lord (1807-1844). New-York Tribune, November 1875, Courtesy Ludington Family Collection.

[3] See “Beauty and the Brick: Illustrated Books & Nineteenth Century Domestic Design.” https://www.hudsonvalley.org/beauty/advice1.html Local doctor Shubael Bartlett (1811-1849) had already used an architectural plan published in 1842 in Cottage Residences, a book of designs for country homes by Davis’ partner Alexander Jackson Downing (1815-1852), to build a similar cottage residence on Lyme Street.

[4] See Lyme Land Records 33:71; Landmarks of Old Lyme Connecticut (Ladies Library Association of Old Lyme, 1968), pp. 25-27; Genealogical and Biographical Record of New London County, Connecticut (1905), p. 332. Matthew Bacon was elected treasurer of the Connecticut Botanic Medicine Society in 1835, and the federal census in 1850 lists him as a doctor.

[5] See James Hammond Trumbull, The Memorial History of Hartford County, Connecticut, 1633-1884 (1886), pp. 556-7; James Parton, Sketches of Men of Progress (1871), p. 145.

[6] Lyme Town Meeting Records, April 7, 1851; Lyme Land Records 38:305, 38:310. Professor Twining issued his initial engineering report in 1849. See New London Engine House and Turntable Archaeological Preserve (2003). http://www.iaismuseum.org/research-and-collections/preserve-booklets/preserve-booklet-new-london-engine-house.pdf Also see Reuben Champion, Jr., to sister [Susan Champion Avery], June 16, 1852, LHSA.

[7] Ian Hubbard, Crossings: Three Centuries from Ferry Boats to the New Baldwin Bridge (1993), pp. 18-22. “America: November and December, 1867,” in John Forster, The Works of Charles Dickens (1899), Vol. 35, p. 403. Landmarks of Old Lyme, p. 27.

[8] Landmarks of Old Lyme, p. 24. Martha J. Lamb, “Lyme: A Chapter in American Genealogy,” in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. LII (February 1876), p. 313.

[9] Ellen Noyes Chadwick to Martha J. Lamb (Coleman), November 5, 1874, in Martha J. Lamb Papers, New York Historical Society. Ellen Noyes Chadwick to Charles Noyes Chadwick, September 23, 1878, LHSA.

[10] Ellen Noyes Chadwick to Martha J. Lamb (Coleman), November 5, 1874, New York Historical Society. Mrs. Chadwick refers to New York artists Frank Bellew (1828-1888), a talented cartoonist and magazine illustrator, and Charles Parsons (1821-1910), who served as art director for Harper’s Weekly from 1863-1889. Fidelia Bridges (1834-1923) may have returned to Lyme in 1875, the year that she painted Thistles in a Field.

[11] The Sound Breeze, June 19, 1874, LHSA.

[12] “Put up at Bacon House,” Clark Voorhees noted in his diary on August 21, 1896. On September 2 he added: “Went across to Saybrook meadows this p.m. got several yellowlegs & meadow larks. Sketched later. Near Bow bridge.” LHSA.

[13] Woodrow Wilson to Bertha Chadwick Trowbridge, September 6, 1905. Photocopy LHSA.