Exhibition Notes

Exhibition Note: “Ocular Evidence” of Black History: Thomas Hope’s “Trompe L’Oeil U.S. One Dollar Note” and Blanche K. Bruce

ON February 8, 2023

by Amy Kurtz Lansing

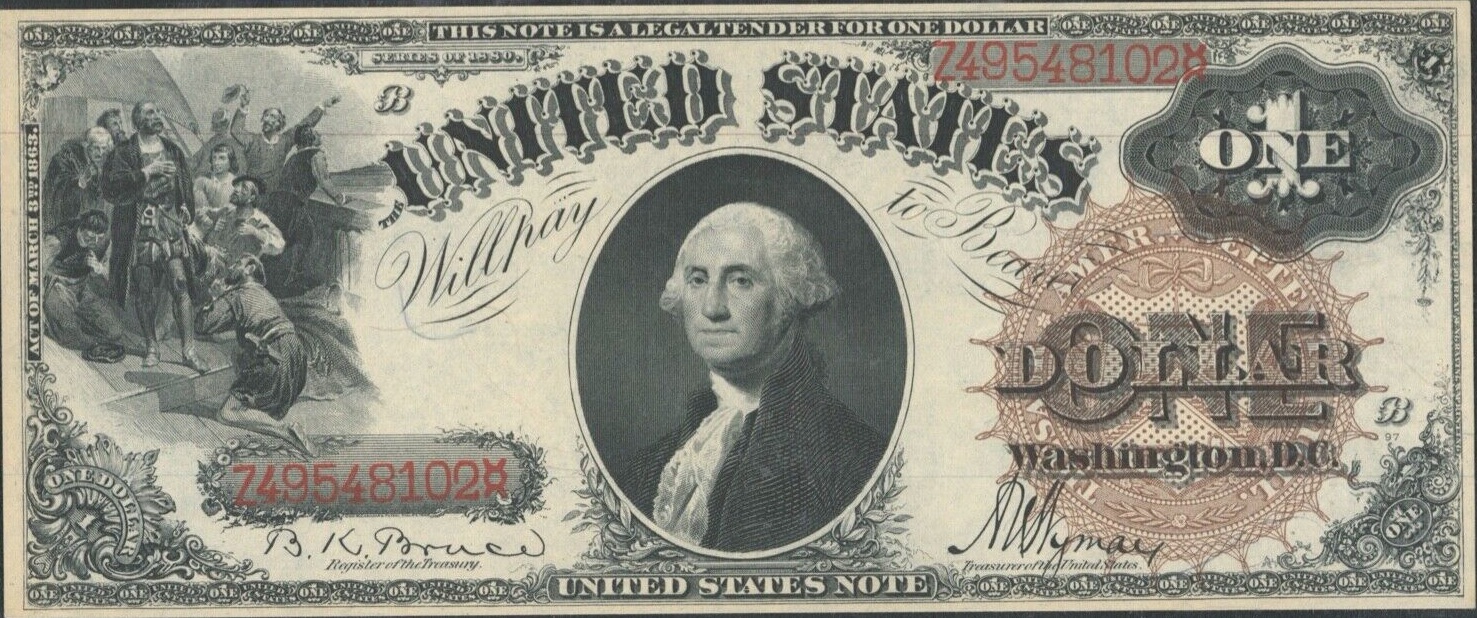

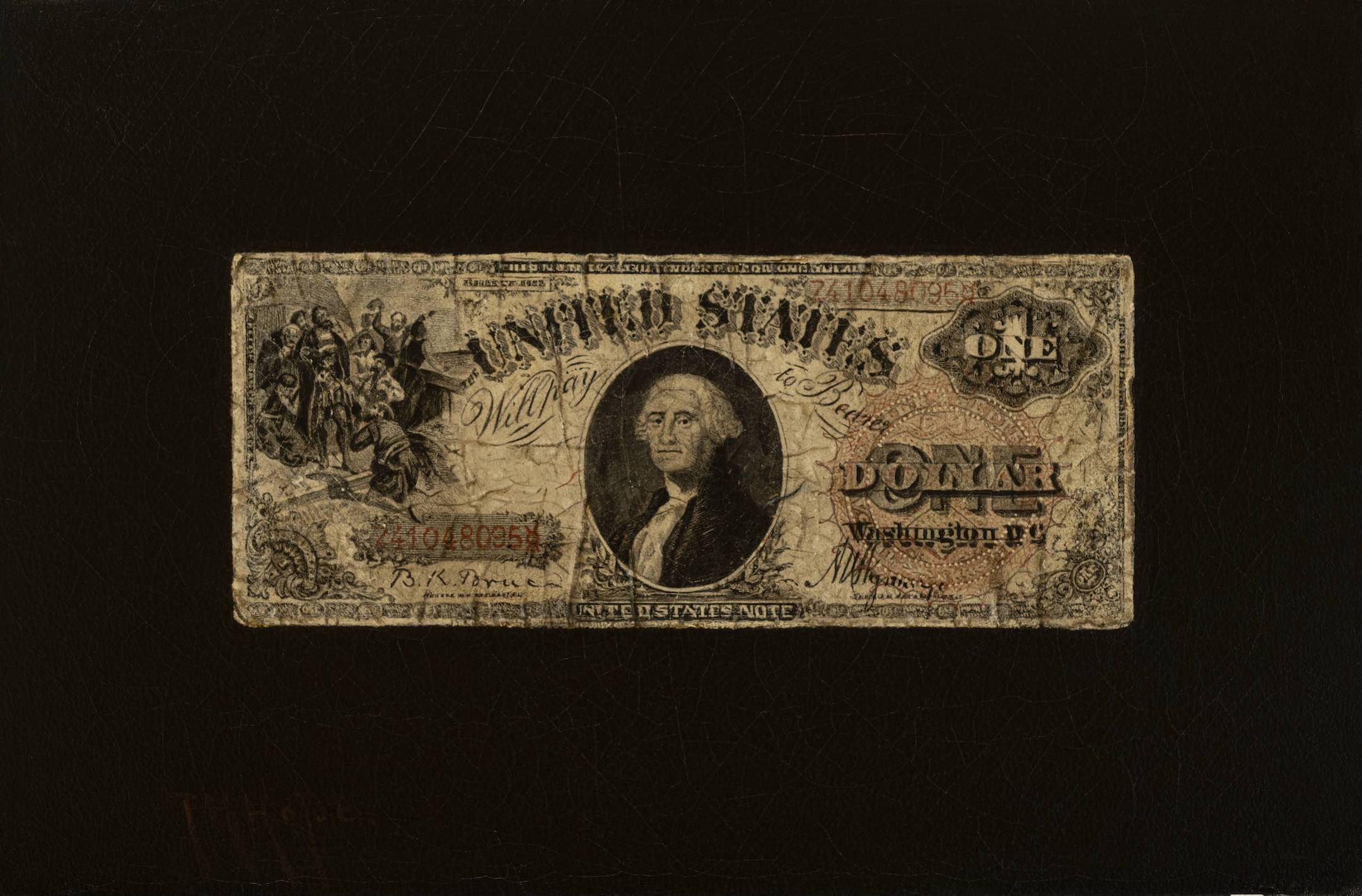

Featured image: Thomas H. Hope, Trompe L’Oeil U.S. One Dollar Note, after 1883. Oil on panel, 7 ½ x 11 ½ in. Florence Griswold Museum, Bequest of Arthur J. Phelan, Jr., 2017.1.13

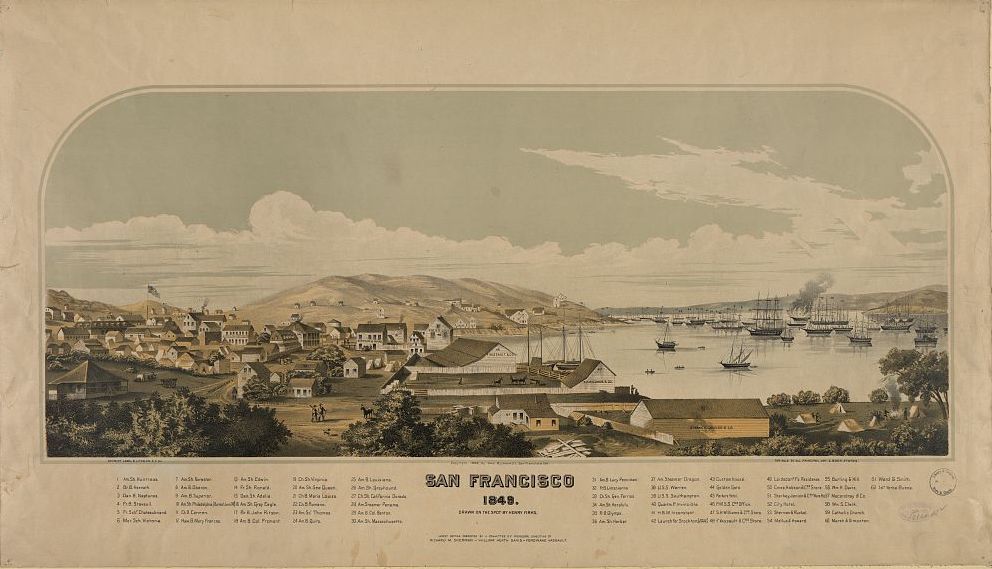

The current exhibition Dreams & Memories includes a painting of a $1 bill by Thomas H. Hope (1832–1926). Money may have been on the mind of the artist, who immigrated from England and had settled in New Haven as a music teacher by 1860. He served as a musician in the 17th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry regiment during the Civil War. Afterward, he enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, becoming a painter of still life based in Connecticut.[1]

This depiction of a dollar has been executed in a hyper-realistic style known as trompe l’oeil, a French term meaning “to fool the eye.” The convincing currency replica is so tangible we almost believe we could pluck the dollar from the wall. While Hope mainly seems to have focused on traditional still-life subjects such as food, wine, and decorative objects, like the trompe l’oeil painters William Harnett, John Haberle, and John F. Peto, he inserted images of newspaper, or in this case, currency, to add verisimilitude to his depiction and display his skills of observation and replication. Artists who worked in this genre were particularly attracted to money both for the subject’s allure and for the extra thrill of walking the line between creativity and counterfeiting.

But amid the apparent certainty that what we see before us is a dollar bill are details that many Americans have long ignored. By looking closely at those details, we can revisit the Reconstruction era when for a few years following the South’s defeat in the Civil War, the racial balance of power was recalibrated until it was undermined by the rising forces of Jim Crow. For Black History Month, Trompe L’Oeil U.S. One Dollar Note (after 1883) can open our eyes to a fuller, more inclusive picture of this nation’s past.

Series 1880 $1 Legal Tender example. Image from Ebay

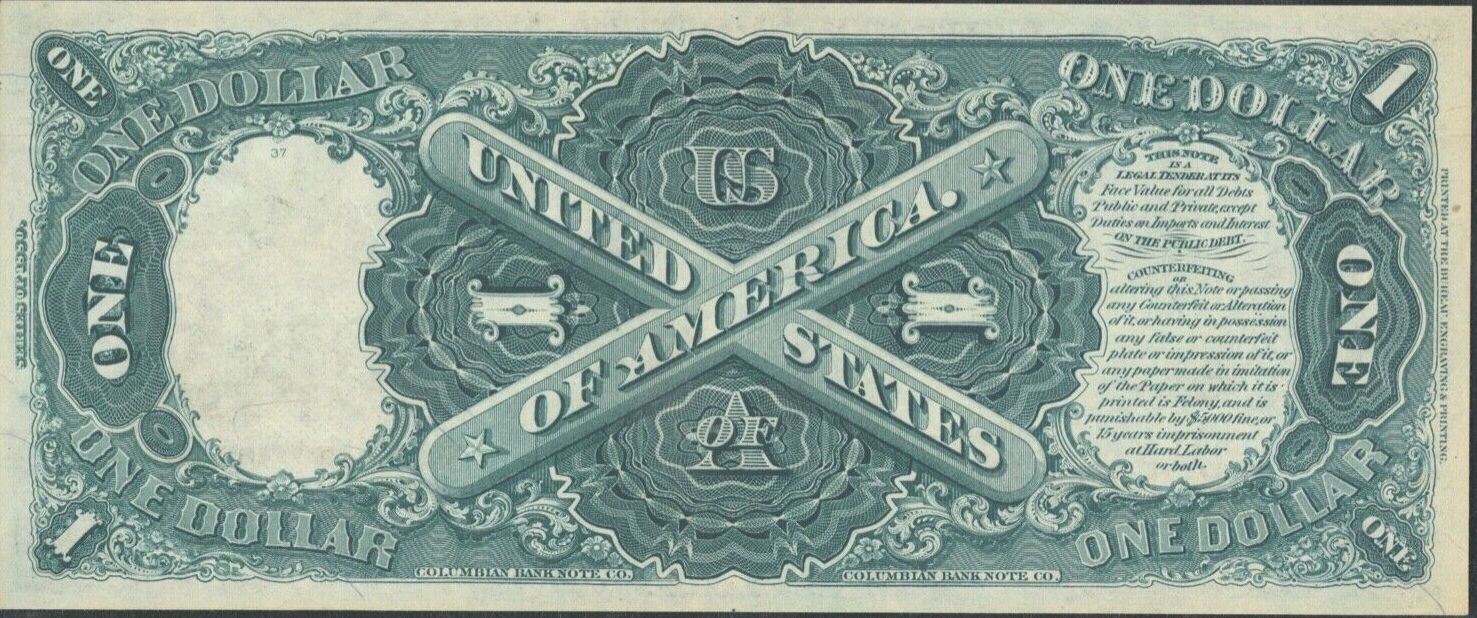

Back of Series 1880 $1 Legal Tender example. Image from Ebay

The dollar Hope used as his model is an example of Series 1880 $1 Legal Tender, a type of paper currency first issued by the federal government during the Civil War to address the extreme need for money in an era of considerable expenses.[2] George Washington’s likeness, based on a portrait by Gilbert Stuart, appears at the center of the bill, and to the left, we see a vignette from William Henry Powell’s Columbus in Sight of Land, images that allude to America’s history.[3] The pairing of those pictures on currency suggests a link between Columbus’s arrival in this hemisphere on his colonial expedition and the founding of the United States, with Washington as its first president. The dollar’s iconography was drawn from the past to suggest the U.S.’s historical roots and the Union’s continuity despite the divisiveness of the Civil War during which the bill was designed and first circulated.

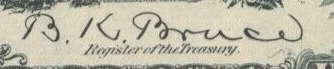

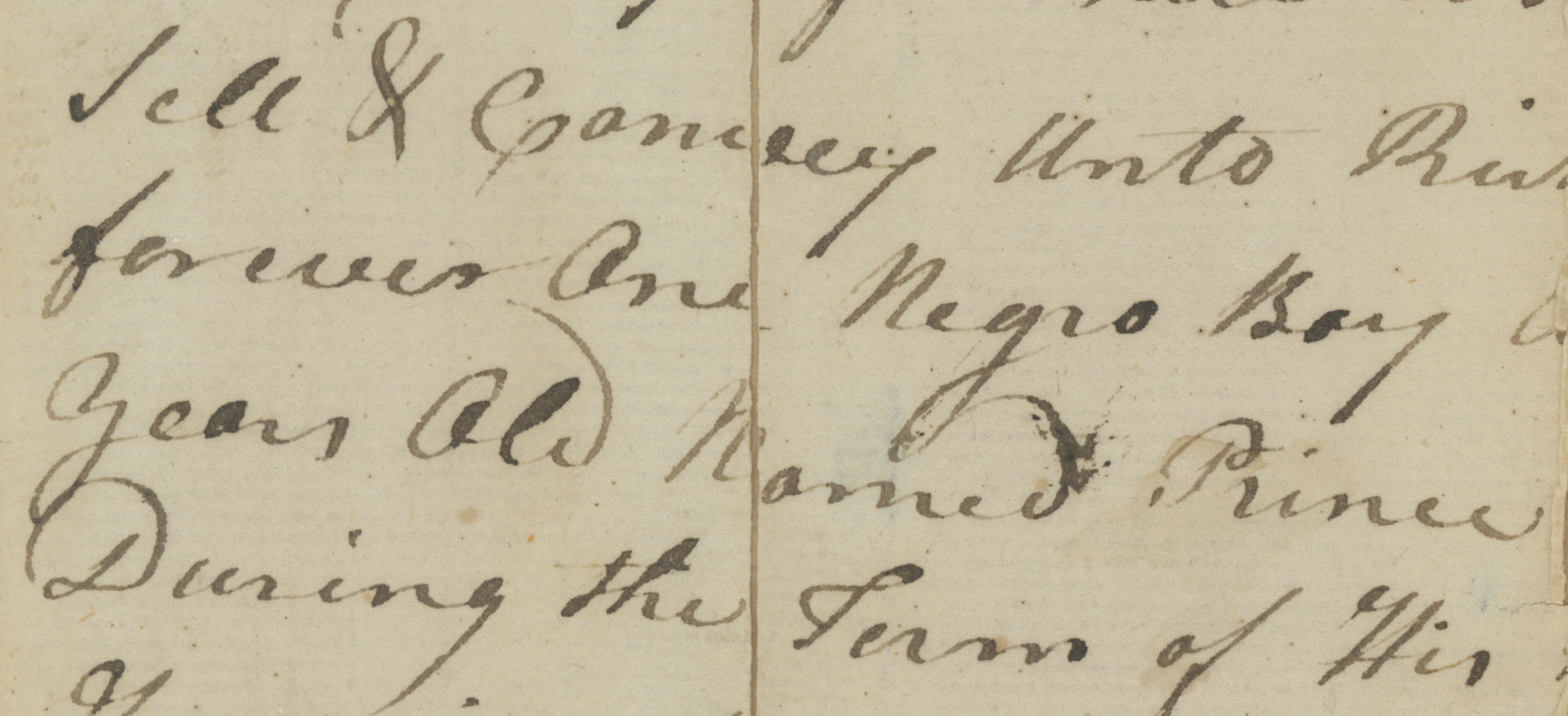

Signature detail, from lower left of bill

In contrast to these historical references, the $1 bill incorporates the names of contemporary government officials, who, during Reconstruction, included Black Americans in unprecedented numbers. Notably, the signature of one of them, Blanche Kelso Bruce (1841–1898), as Register of the Treasury is visible to the left of center. It is intriguing to consider what may have inspired the artist Hope, who had participated in the Civil War on the Union side in 1865, to depict this dollar bill that reflects so profoundly the transformation underway in post-bellum America.

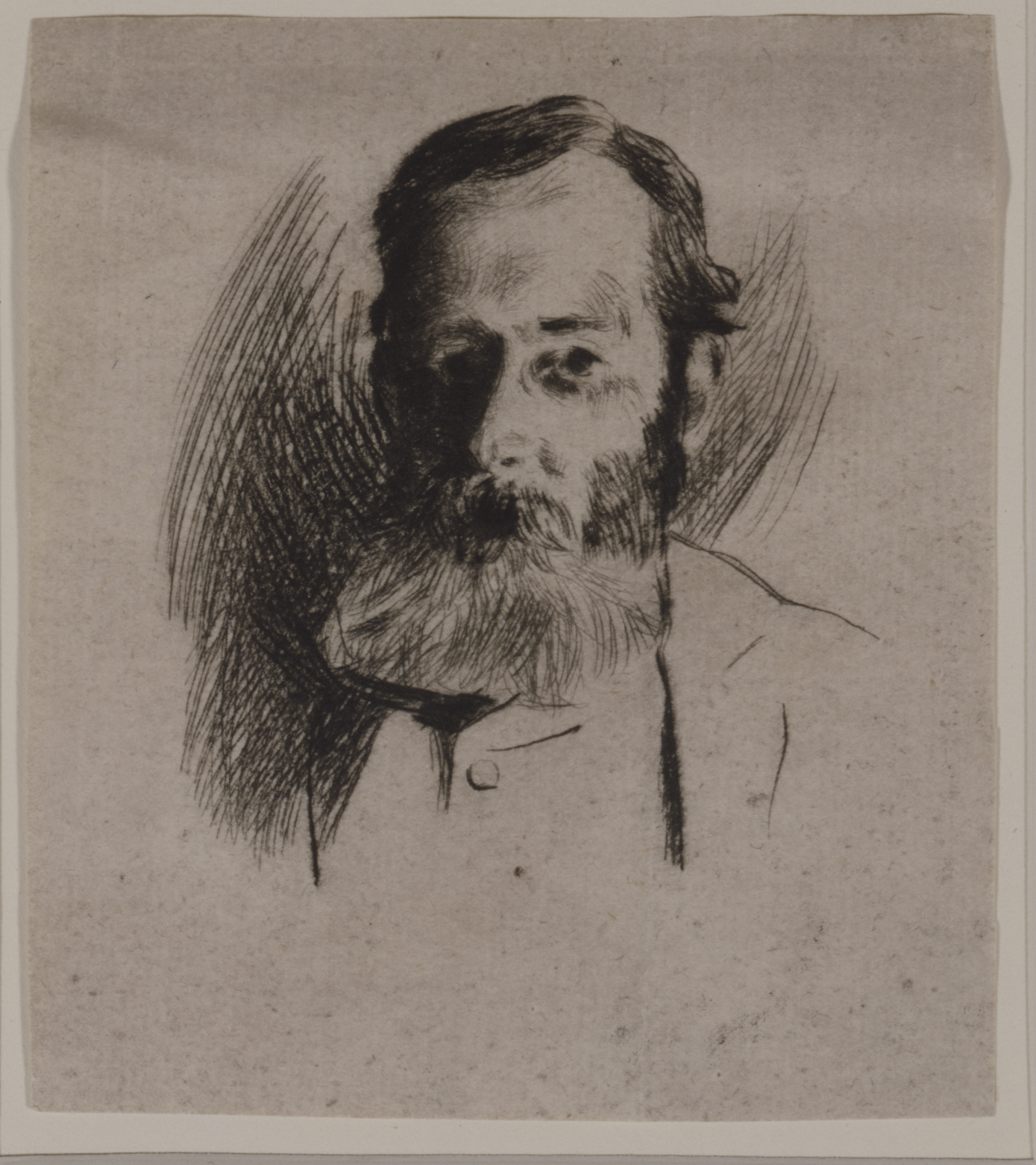

Matthew Brady, Sen. B.K. Bruce, Mississippi / Brady, Washington, D.C., between 1863 and 1890. Library of Congress, https://lccn.loc.gov/2011649218

Bruce’s career embodied both the promise and the obstacles faced by Blacks in his era. He was born into slavery in Virginia to Polly Bruce, the mother of eleven children who was owned by planter Pettus Perkinson, Blanche’s father. Originally called Branch, the mixed-race Bruce grew up as personal servant to his own white half-brother. While laws typically forbade enslaved people to obtain an education, he learned to read from his half-brother’s tutor. The Perkinsons moved their enslaved workers to Missouri in the 1840s, back to Virginia, and then to Mississippi and Missouri, hiring them out on a variety of contracts.[4] Bruce learned printing in Missouri and was hired out to labor in tobacco production. While he and his siblings largely remained together during these peregrinations and gained some ability to spend off-work hours as they preferred in activities such as reading, their wages were not theirs to keep.[5]

When his master joined the Confederate Army, Bruce departed in 1861 for free soil. He later recalled “after the firing on Fort Sumter and the opening of the war of the rebellion (I) concluded (that) I would emancipate myself. So I worked my way to Kansas, and became a free man before the emancipation proclamation was issued by President Lincoln.”[6] It was at this time that he changed his name, taking Blanche in place of Branch and claiming the last name “Bruce” for himself.[7]

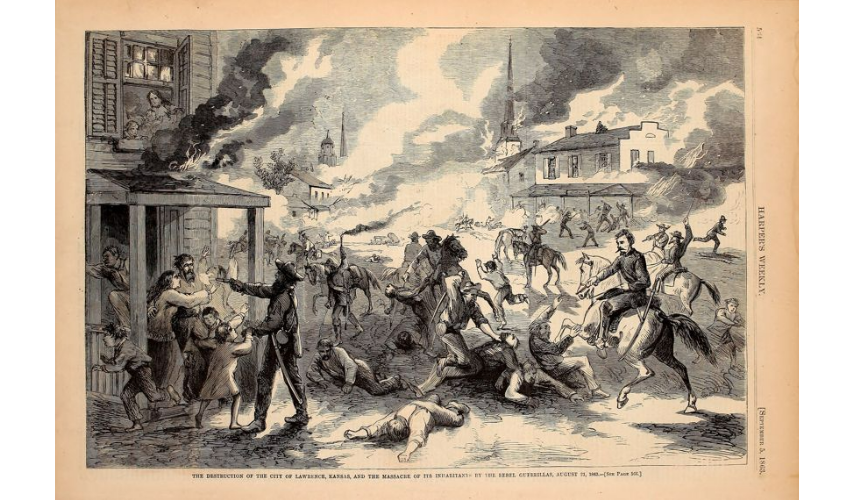

Raid by William Quantrill and his guerrillas on Lawrence, Kansas, Harper’s Weekly, September 5, 1863. Courtesy Internet Archive

The young man became a teacher in Lawrence, Kansas, a center of abolitionism, where he narrowly escaped a bloody raid in 1863 by slavery supporters from Missouri.[8] Before the war’s end he founded the first school in Missouri for Black children. Some sources say that in the war’s aftermath, Bruce spent time in Oberlin, Ohio, studying alongside a friend attending Oberlin College with his own hope of preparing for the ministry. Reports conflict about whether he withdrew because of insufficient funds or whether the institution has any record of his attendance.[9]

Work as a porter on a Mississippi River steamboat brought Bruce to Mississippi in 1868. Drawn by economic opportunity and his determination to make a mark, he became involved with local Republican politics after he heard the future governor give a stump speech. As a man who had grown up literate and in close proximity to white planters, Bruce made inroads with the Republican reformers helping to implement Reconstruction by building interracial democracy in Mississippi under federal oversight. District military commander General Adelbert Ames appointed him register of voters in Tallahatchie County, a role in which he worked to ensure the franchise for those formerly enslaved.

African Americans casting ballots in the first reconstruction election in the state of Virginia, “The First Vote,” Harper’s Weekly, November 16, 1867. Library of Congress

In 1870, Bruce became sergeant at arms for the state Senate. He built a power base in Bolivar County as sheriff, tax collector and editor of the Floreyville Star newspaper, offices in which he was able to address the needs of Black constituents as they constructed a political and social order that at last included them as citizens. As county education superintendent, Bruce developed a fully funded, if segregated, school system for Blacks. Named to the state board of levee commission in 1872, he raised revenues to build flood-control embankments on the Mississippi to help farmers.

Reconstruction politics were a turbulent mix of African American aspiration and achievement beset by whites’ machinations to control, restrict, and ultimately demolish the process. Mississippi’s white Republicans split in 1870 into factions, the more conservative of which ignored Blacks’ calls for civil rights. As an ally of the state’s radical governor, the more moderate Bruce was encouraged to accept the position of Lieutenant Governor but chose instead to put himself forward for nomination by Mississippi’s Republican-controlled legislature for the U.S. Senate seat the governor had vacated. With the support of his fellow Black republicans in the legislature Bruce won the seat, becoming the second Black man to represent Mississippi in Congress and the only formerly enslaved person to hold a Senate seat. He would eventually be the first African American elected to a full term in the Senate, a feat not repeated for ninety years.

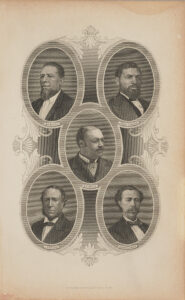

Wellstood & Co., Engraved portraits of five members of Reconstruction Congresses, clockwise from top left: Hiram Revels of Mississippi, James T. Rapier of Alabama, John R. Lynch of Mississippi, J.H. Rainey of South Carolina, with Blanche K. Bruce of Mississippi in center, early 1880s. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2020.26.43

Despite the exertion required to obtain his position in Reconstruction-era Mississippi, Bruce arrived in Washington, D.C., in March 1875 only to be snubbed by the state’s other, white, Senator. While he was embraced by Radical Republicans such as New York Senator Roscoe Conkling, Bruce himself walked a diplomatic line across the minefield of Senate decorum as a Black member with little individual power to address federal indifference to the treatment of Black southerners.

He lent his voice in 1876 to the failed effort to seat a Black Senator from Louisiana and introduced a bill demanding an inquiry into 1875 election violence in his home state of Mississippi. Bruce advocated for Black veterans as well as for education funding. He chaired the Select Committee to Investigate the Freedmen’s Savings and Trust Company following the bank’s failure. Although the committee could not persuade the Senate to reimburse depositors, Bruce deployed some of his own money as well as his political influence to raise funds to reimburse what depositors they could.[10]

He also used his voice to oppose the act excluding Chinese immigrants from the United States and argued for greater equity for Native Americans. As chair of the Select Committee on Levees of the Mississippi River, he urged improvements along its banks for the benefit of those trying to make a living without the disruption of floods. Bruce had invested in Mississippi real estate and become prosperous as the owner of a plantation cultivated by sharecroppers, an economic advantage that increasingly differentiated him from his constituents.

When white Democrats turned the political tide in Mississippi in 1880, Bruce’s tenure in the US Senate came to an end because there was no longer a path in the state legislature for re-election as a Black candidate. Despite what he had done to nurture equality for Blacks, the gradual dismantling of Reconstruction advances in Mississippi led him to stay in Washington, D.C., as part of the Republican establishment when his Senate term ended in the spring of 1881.

In May of that year, President James Garfield appointed Bruce Register of the Treasury, a nod to Black voters for their support and a testament to Garfield’s conviction that the formerly enslaved should have representation in government. In that position, Bruce signed the bill depicted in Thomas Hope’s painting sometime after the appointment of the other signatory, Treasury Secretary A.U. Wyman, in 1883.[11] The two men served together in office until 1885.

In June 1881, The Christian Recorder newspaper commented on the significance of the announcement that former Senator Bruce would continue in public service as Register of the Treasury:

“A colored man, in the person of Mr. Bruce, now holds a position under the government where every man in the country will soon have daily ocular evidence of the fact that the colored race has received prominent recognition as a part of the body politic. Every circulating note, whether of the United States or national banks, every Government bond, and all other forms of national indebtedness, bear the signature of Register of the Treasury, and from this time onward, while Mr. Bruce continues in his present office, the signature of a man who, twenty years ago, had no rights that white men were bound to respect, will be necessary to give currency to the circulating notes of the United States and national banks, as well as to attest the correctness and completeness of nearly all the transactions of the Treasury of the United States. The signature of Blanche K. Bruce on the circulating notes of the United States furnishes emphatic illustration of the great results that have been accomplished by the war for the suppression of the rebellion.”[12]

Christian Recorder, June 23, 1881, p. 1. Internet Archive

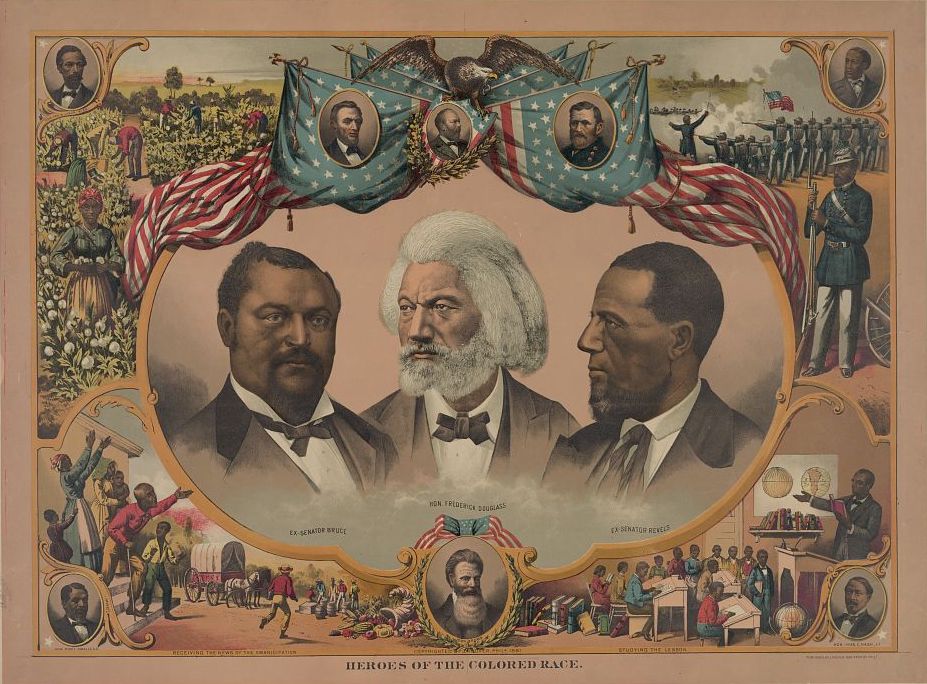

Bruce continued as Register of the Treasury until 1885 and was named again in 1897 to the post, which the Republican party reserved for a prominent Black member in the late nineteenth century. From his home in Washington, D.C., he was a major force in Mississippi Republican politics throughout the 1880s and was a delegate to every Republican national convention from 1869 to 1896. In opinion of the period, Bruce was considered the most well-known person of his race after Frederick Douglass.[13] Bills with Bruce’s name circulated for years after the promise of Reconstruction embodied in his signature was dismantled. But the persistence of his name on surviving examples of the dollars and in the indelible image Hope painted, remind us to celebrate Bruce’s legacy.

Blanche K. Bruce, Frederick Douglass, and Hiram Revels, in J. Hoover, Publisher, Heroes of the Colored Race, 1881. Chromolithograph. Library of Congress

[1] Record for Thomas H. Hope, Connecticut Military Census of 1917, Hartford, CT, Connecticut State Library, via Ancestry.com

[2] Thanks to Dustin Johnson, Heritage Auctions, for confirming the identification of the note. Email exchange with author, February 3, 2023.

[3] William Henry Powell (1823–1879) is best known for contributing the history painting Discovery of the Mississippi by De Soto (1855) to the decoration of the U.S. Capitol rotunda. His oil Battle of Lake Erie (1873) is installed on the United States Senate side of the Capitol. Powell’s depiction of Columbus would later also appear on U.S. stamps. The original oil is currently unlocated, but a work with that title was last recorded in a private collection in New Hampshire. See Inventory of American Paintings.

[4] Sadie Daniel St. Clair, “The National Career of Blanche Kelso Bruce,” Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1947, p. 11, 16.

[5] St. Clair, 21-22.

[6] “Washington Letter,” The Kansas City Times, October 17, 1886, quoted in St. Clair, p. 20.

[7] Bruce, the name Blanche’s mother bore, came from the father-in-law of master Pettus Perkinson, with whom she grew up.

[8] St. Clair, 20-21.

[9] St. Clair summarizes the evidence, p. 22.

[10] See https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/BAIC/Historical-Essays/Fifteenth-Amendment/Legislative-Interests/

[11] Albert U. Wyman (1833–1915) was a Wisconsin banker who went to work at the Treasury in Washington, D.C. beginning in 1863. Nominated by President Ulysses S. Grant, he served as Treasurer of the United States from 1876 to 1877. In 1883, President Chester A. Arthur nominated Wyman to be Treasurer of the United States for a second time. He occupied the position from April 1, 1883, to April 30, 1885.

[12] Prof. W.S. Scarborough, “The Claims of the Colored Citizen Upon the Republican Party,” The Christian Recorder, June 23, 1881, p. 1

[13] “Hon. Blanche K. Bruce Dead,” The Atlanta Constitution, March 18, 1898, p. 1.