By Carolyn Wakeman

Featured Image: Kendall Banning, The Road to Eden (showing the road to the meetinghouse), Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

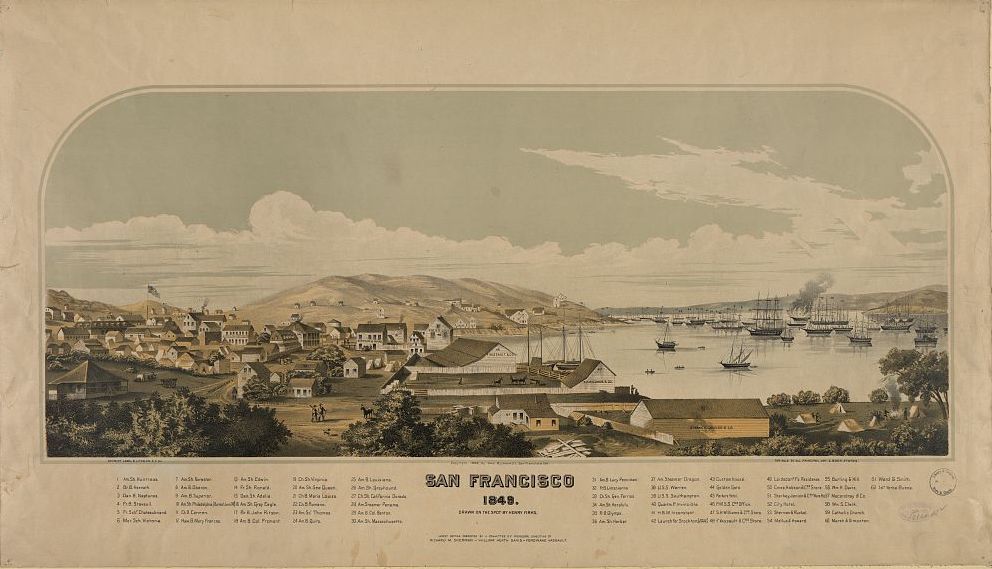

Early Connecticut towns were required by law to provide food and lodging for strangers. In 1644, the year that Saybrook became part of the Connecticut Colony, the General Court in Hartford ruled that each town must choose “one sufficient inhabitant to keepe an Ordinary, for provision and lodgeing in some comfortable manner, that such passengers or strayngers may know where to resorte.” More than two decades later the newly established town of Lyme complied with the Court’s mandate. A town meeting in 1670 decided that Mr. John Lay, whose farm bordered the road to the Meetinghouse, “shall keep the ordinary of this town.”[1]

When a town meeting in 1697 decided that Edward DeWolfe (ca. 1646-1712) “shall keep a house of entertainment upon the Road,”[2] three other Lyme inhabitants had served as keepers of an ordinary, or inn, licensed to sell “strong drinks.” New London County Court records provide a glimpse of the lodgers DeWolfe entertained in 1700 and 1701 in the house he had recently built near his sawmill, on today’s Sill Lane. Among them were a wayward husband, an unaccompanied woman, and four deckhands from an ice-bound ship.

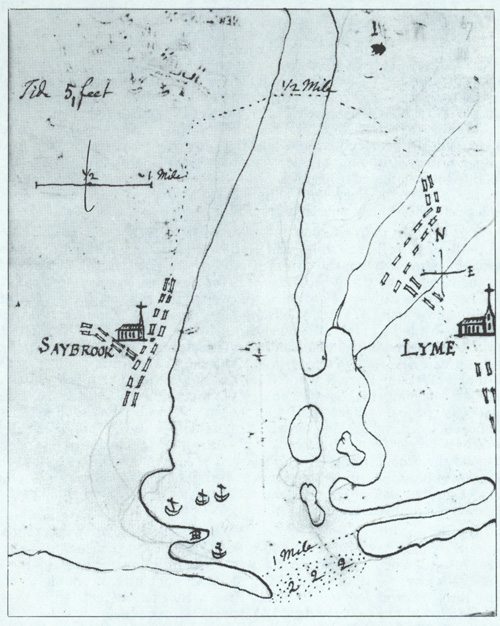

Ezra Stiles, Map of Lyme, 1768. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

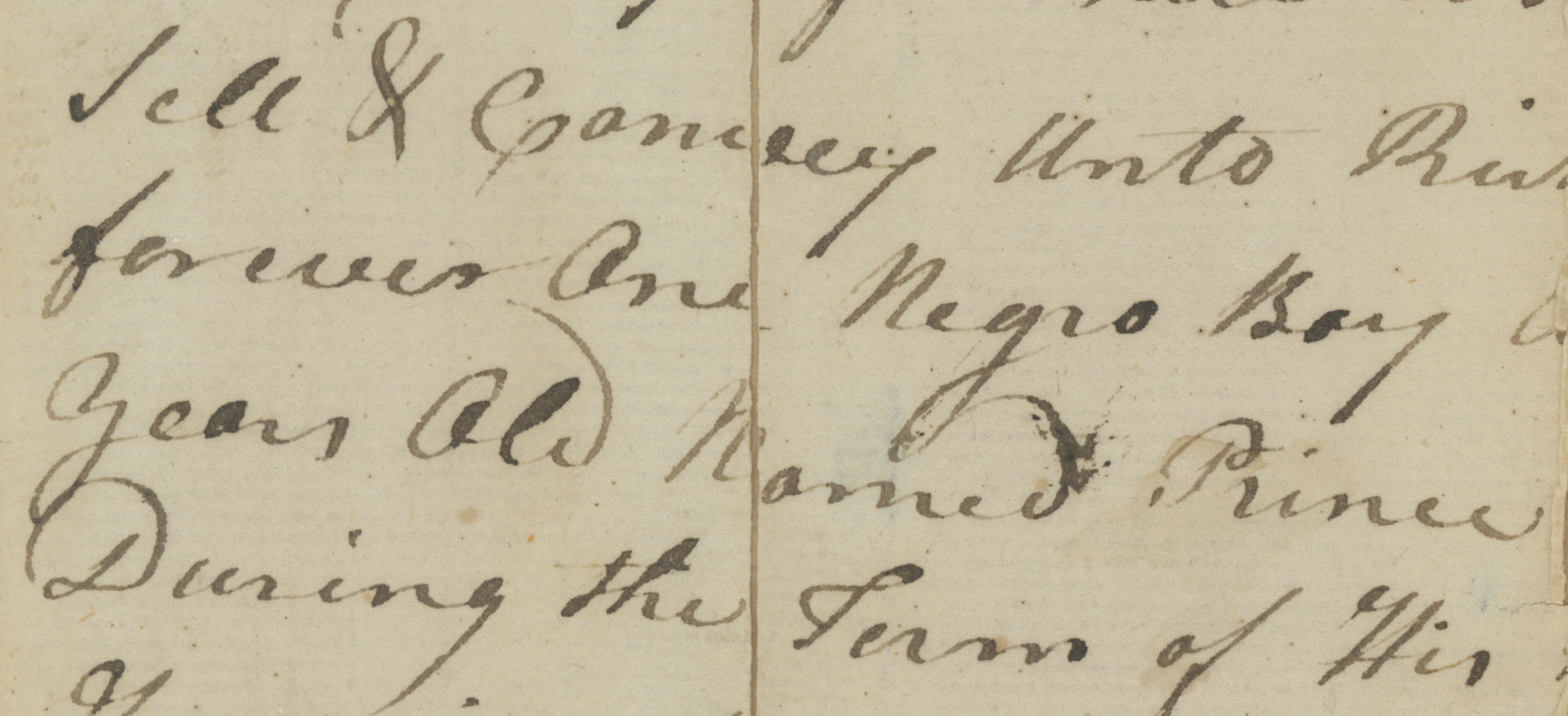

Josiah Raynor (1665-1742), a mariner from Southampton, had purchased a home lot in Lyme in January 1700, and in December his wife Sarah gave birth to their daughter Elishabe. A month earlier in November the New London County Court found Raynor guilty of lascivious carriage, or wanton sexual conduct, while staying at DeWolfe’s boarding house. When Raynor returned there on the last day of militia training in November, Court records state. Rebecca DeWolfe, Edward’s wife, found him in bed with Sarah Kelly. Kelly, apparently unaccompanied, had recently arrived and was looking for lodging. The couple “tarried there together until after milking time in the evening.” A young boy observed them in bed, and DeWolfe’s daughter Mary DeWolfe Stocker (1681-1704) also saw them “together apon the bead rapt up in the coverlet.”[3]

Later when the couple came out and sat by the fire, Raynor “had his legge upon the young Womans Lapp and boath hands about her neck.” After John Lee, another boarder, asked him what his wife thought of his “horable” behavior, the couple retired to another room for the rest of the night. Two months later, after Edward DeWolfe filed charges against Raynor for “very uncivill and Lascivious carriage in his house,” seven additional witnesses testified about his lewd behavior.

Several recalled that a few weeks after spending a night with Kelly, Raynor repeatedly attempted to put his hands under the apron of Philadelphia Thomson, a boarder at Isaac Watrous’s house. She had “bid him be quiet or I will strike you downe,” she testified, and she had also asked why as a married man he would act so shamefully. Raynor pleaded guilty, asked for leniency, and the Court reduced his fine from five pounds to four pounds.[4]

Raynor had an adventurous past. According to a Long Island genealogy, he was involved in “piracy escapades” as a crewman on privateer vessels prior to 1700, and a Southampton historian specifies that he “went out a privateering (that is pirating) with Capt. Tew.” Captain Thomas Tew, based in Newport, had turned from government-sanctioneed privateering to open piracy with the consent of New York governor Benjamin Fletcher (1640-1703). Raynor appears to have signed on as a deckhand on the 70-ton sloop Amity bound for the Indian Ocean in 1693. Reports of the voyage state that an interlude in Madagascar offered crewmembers an opportunity for dalliance with local women.[5]

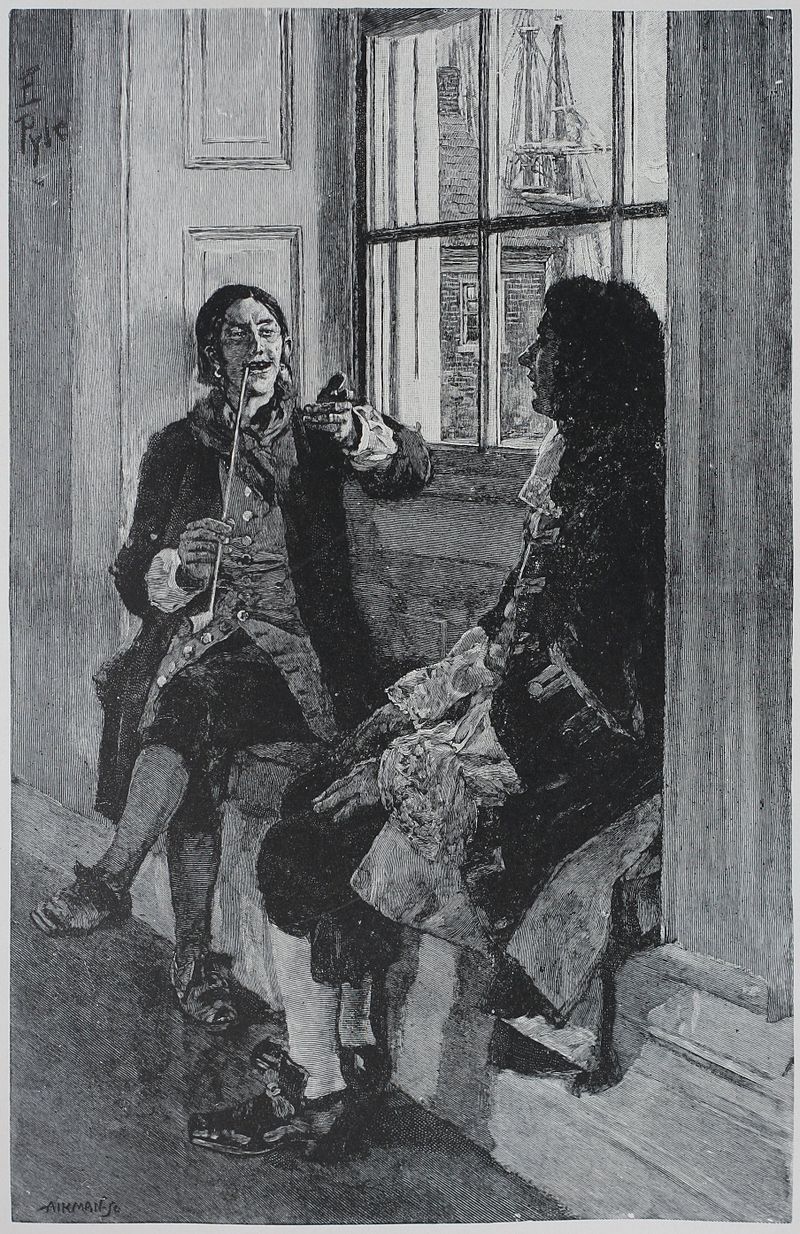

Howard Pyle, Thomas Tew conversing with Gov. Benjamin Fletcher, Harper’s Magazine, November 1894

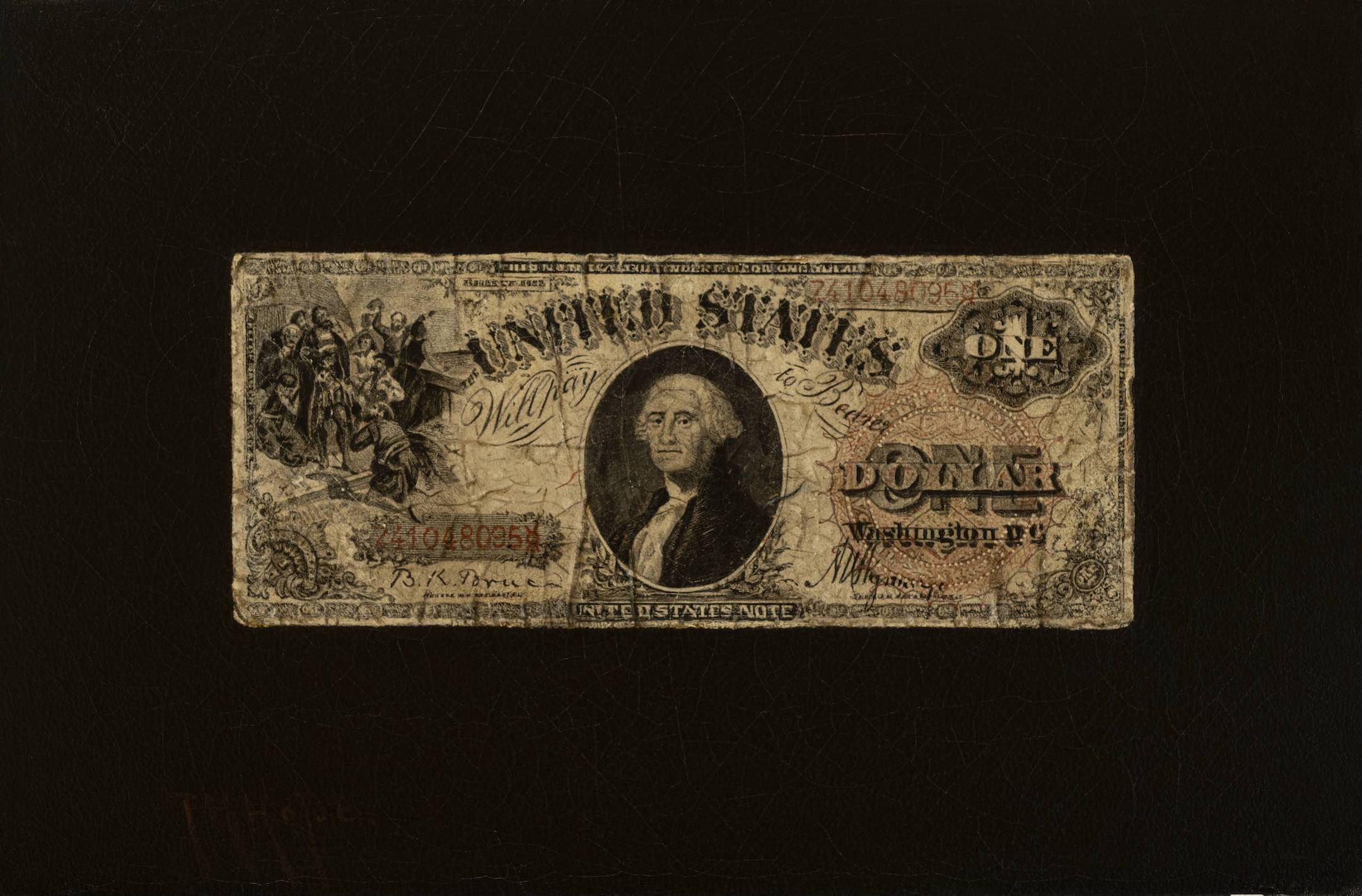

When Raynor came ashore on eastern Long Island with his portion of the loot from a vessel plundered in the Red Sea, the Suffolk County sheriff arrested him and seized his chest, which contained “a considerable treasure,” worth an estimated 1,500 pounds. Raynor’s arrest was brief. Through a friend he appealed to Governor Fletcher, offered a gift of 50 pounds, and secured not only his release but the return of his chest.[6] The recent discovery of late 17th century Arabic coins in a Rhode Island orchard and three sites in Connecticut indicates that pirates returned to Southern New England after preying on vessels in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. A coin discovered in 1988 on the west bank of the Niantic River, linked to the notorious pirate raids of Capt Henry Evers, suggests that treasure plundered in the Red Sea found its way to the Lyme region.[7] Ongoing research may shed more light on Raynor, whose “piracy escapades” likely allowed him to purchase a home lot in Lyme.

Arabian silver coins found in Middletown, RI, in 2014. Courtesy of the American Numismatic Society via Flickr

In 1702 New London court records again reference strangers lodging at DeWolfe’s ordinary, after he entertained four sailors from a vessel stranded in the ice-bound Connecticut River. DeWolfe sued John Arnold (1651-1725), a Boston mariner and anchorsmith, for debts owed to him for lodging Arnold’s crewmen the previous winter. DeWolfe said he had provided the crew with “vitals and drink” until the ship was freed, but Arnold refused to pay the charge of 18 pounds and bargained out of court, offering to pay for the men’s food and 5 pounds for their drink if DeWolfe would not charge for lodging. When DeWolfe filed suit for the full debt, Arnold threatened to sue him for illegally boarding the crew without official permission from New London’s selectmen.

Arnold then claimed that DeWolfe’s hospitality was injurious and that he had caused the crew “to spend excessively at your house whereby the work of the sloop was neglected and so became frozen up that she could not get out to proceed their voyage to the damage of L100 silver.” Court records do not include the outcome of the case, suggesting a settlement outside of Court.[8] But like the previous year’s case involving DeWolfe’s house of entertainment, Court testimony offers an important glimpse of social life in Lyme as the town’s mercantile trade developed at the turn of the 18th century.

[1] Special thanks to Dominic F. DeBrincat for sharing detailed research on the New London County Court records. Charles J. Hoadly and Hammond J. Trumbull, eds. The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut I:103 (June 3, 1644); Jean Chandler Burr, Lyme Records, 1667-1730 (Stonington, 1968), p. 4.

[2] Burr, p. 83.

[3] Lyme Land Records 2:207 (January 1, 1700); Vital Records of Lyme Connecticut, To the End of the Year 1850, ed. Verne M. Hall & Elizebeth B. Plimpton (Lyme, 1976), p. 256: “Elishabe was Borne….4 Desembr 1770.”

[4] Ibid.

[5] The Raynor Family of Long Island http://longislandgenealogy.com/Surname_Pages/raynor.htm James Truslow Adams, History of the Town of Southampton (Bridgehampton, 1918), p. 134; Kevin P. McDonald, ‘A Man of Courage and Activity’: Thomas Tew and Pirate Settlements of the Indo-Atlantic Trade World, 1690-1720 (Working Paper, UC Santa Cruz, 2005), pp. 3, 16.

[6] Adams, p. 134.

[7] James Bailey, “Late 17th Century Arabian Coins Found in Southern New England: Uncovering the Evidence and History of Red Sea Piracy in Early America,” The Colonial Newsletter: A Research Journal in Early American Numismatics (August 2017), p. 4576 ff.; “An Amateur Anthropologist Found a 17th-Century Coin That May Solve the Mystery of an Infamous Pirate Heist,” ArtNet News (April 6, 2021). https://news.artnet.com/art-world/arabian-coins-pirate-heist-1957291 See also Jim Littlefield, “A 17th-century Arabic coin discovered locally may be tied to pirate plunder,” The Day (April 28, 2021).

[8] DeBrincat, pp. 206-207; transcript, Ely-Plimpton Papers, Box 8. Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum.