Learn

Boardinghouse

- The Museum will be closed Sunday, April 9 in observance of Easter.

by Hildegard Cummings, independent art historian and curator

Boardinghouses

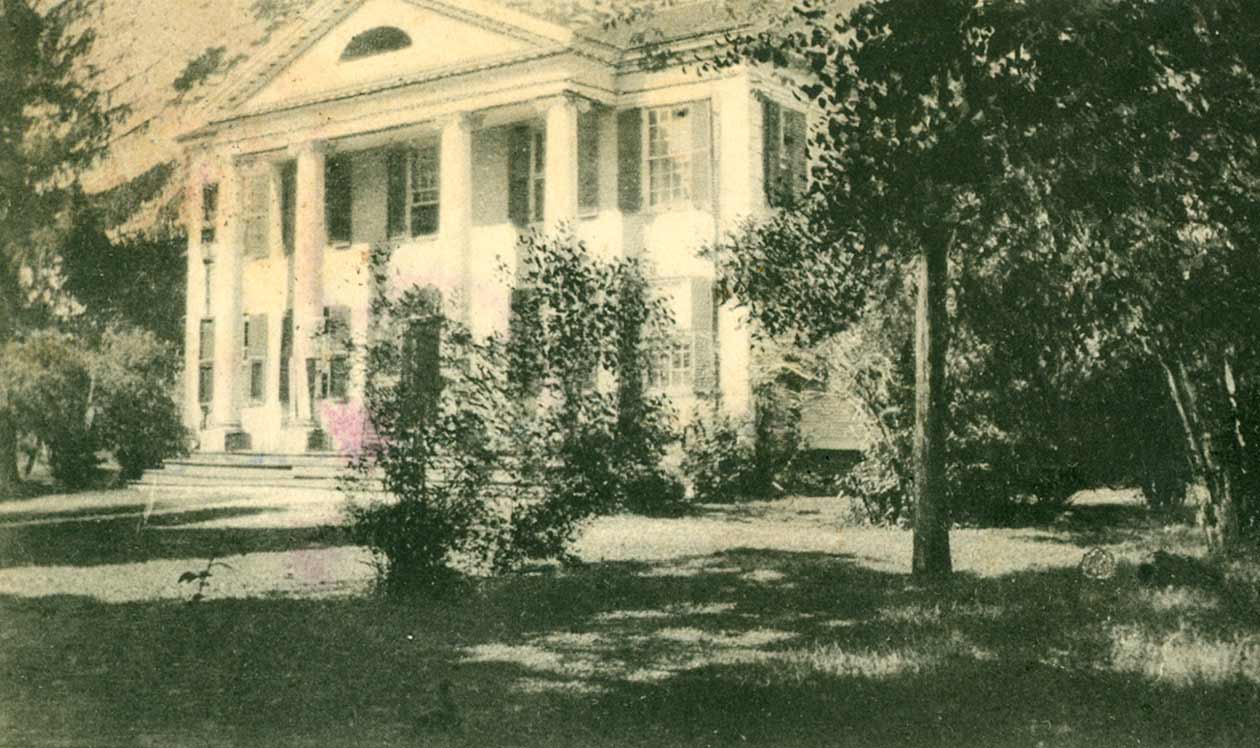

In the summer of 1900 a boardinghouse for artists began operation in the quiet shoreline town of Old Lyme, Connecticut. For the next two decades Miss Florence Griswold’s house on Lyme Street was home to one of the most famous art colonies in America and critical to the development of American Impressionism. This is a special story, but boardinghouses, where people paid to live and eat with others, once affected the lives of many Americans.

The boardinghouse era, from about 1875 to 1920, came into being with the burgeoning of cities. By 1910 as many as one-third to one-half of urban Americans had been boarders at some time or lived in a home that had boarders. Young people who left farms and villages behind, and even newlyweds and families, sought inexpensive places to stay, where they could be guided in the ways of the city and sheltered from undesirable influences.

To meet this need, widowed or married women who had to earn money offered space in their homes. In an era when it was considered degrading for a woman to have a job, caring for boarders was seen as an extension of her domestic sphere, so was more palatable to the world at large.

Inspired by this model, textile-mill owners in Massachusetts and Connecticut housed women employees in boardinghouses aimed at keeping them healthy, safe, and moral. Immigrants often began their American life as boarders. Most boardinghouses, however, whether in cities or towns, were in middle-class homes, where a family atmosphere prevailed. Guests were accepted on the basis of referrals, recommendations, or interviews. In time, people with special interests or needs, such as lawyers, sailors, actors, or artists, gravitated to boardinghouses that catered to them. The low cost of boarding continued to be a draw. The bond of fellowship had become another.

An important variant of the American boardinghouse appeared at the end of the 19th century: the summer boardinghouse. These were in homes in rural areas that could be easily reached from a city by train or boat.

Disagreeable aspects of city life had created in urban dwellers of all social classes a yearning for nature, so those who could afford to flocked to seashores, mountains, and farms, seeking respite from city and work. They wanted fresh air, leisure, and fun.

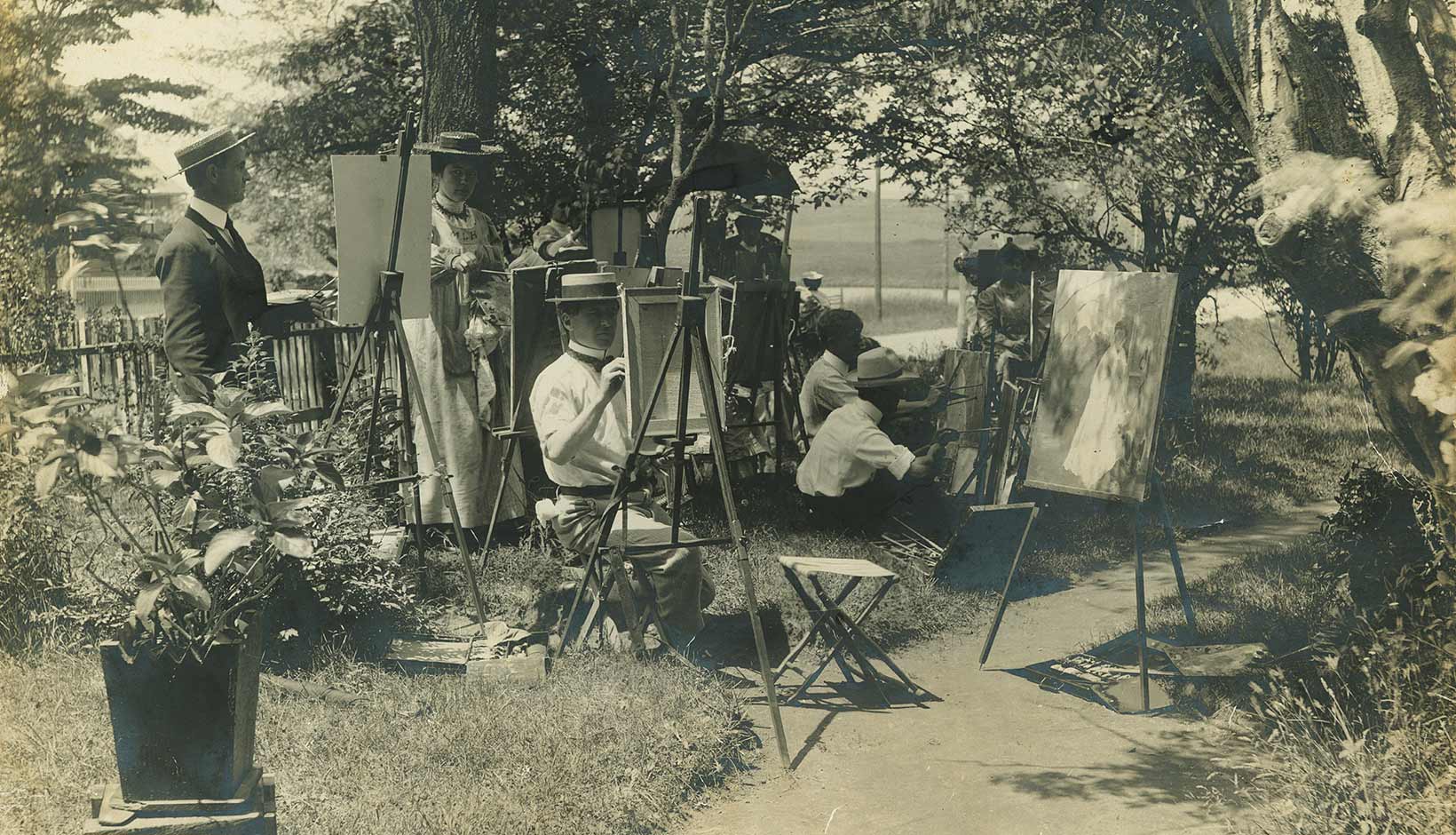

Landscape artists were also looking for an inexpensive summer escape from the city but with a difference: they wanted to be able to work as well as play. They had for some years been painting en plein air — out of doors.

In the 1860s and 70s, they tended to travel — to the countryside alone or in small groups, finding housing where they could. One or two at a time might board in the spare room of a private home, while the more affluent stayed in hotels and the poorer in tents. By the 1880s, however, their studies abroad had introduced American artists to art colonies, such as those at Barbizon and Giverny in France, and now they too wanted to summer in a quiet country spot with fellow artists, apart from vacationers and tourists. Some rural American boardinghouses, in locales rich with natural beauty and the feel of an earlier, simpler America, provided such an experience.

In the Long Island village of East Hampton, Aunt Phebe Huntting’s place on Main St. and Annie Huntting’s “Rowdy Hall” were mainstays of what was from about 1875 to 1890 the most popular art colony in America. In Greenwich, first on a farm and then from about 1889 in the historic Bush House in the Cos Cob section of town, the Holley family hosted artists such as John Henry Twachtman, Childe Hassam, and Theodore Robinson. The Bush-Holley House became home to the earliest Impressionist-oriented art colony in this country. The Griswold House in Old Lyme became the center of the largest and best-known.

Florence Griswold exemplifies in large part the kind of woman who became a boardinghouse operator. She needed money.

She was a single woman with no regular income, living in a large family home that was once elegant but now rundown, and she was the sole support of a sister. In the 1880s, her stately Late Georgian house had been converted into a small school for girls, which she had run with her mother and another sister (both deceased by 1900) and her surviving sister (mentally ill in 1900).

Eventually it had failed. In the summer of 1899, a vacationer boarding at Florence Griswold’s house was Henry Ward Ranger, a respected landscape painter from New York City, who liked the place and its surroundings so much that he proposed to return the next spring with artists who would help him create an American Barbizon there. Florence Griswold readily agreed.

She knew French, literature, art, and music, yet had also of necessity learned to do demanding house and yard work. While others of her era might look down on artists as bohemian, unreliable, even rowdy, Florence Griswold admired their creative talents, enjoyed their diverse personalities, and relished the opportunity to contribute to their success.

The artists who came to her home in 1900 and afterward were men (and an occasional woman) with established or growing reputations in the American art world. Generally in their late thirties or early forties, their student days were behind them and they had already begun or were about to win prizes at major exhibitions and election to prestigious art societies. Most had studied abroad; a few had been born there.

The early arrivals called themselves the “School of Lyme” and were, under Ranger’s leadership, committed to transforming the poetic realism of French Barbizon painting into an American mode they called Tonalism.

To serve them adequately, Miss Florence obtained the help of a cook, a maid or two, and a farm manager. To provide for more of them, she set about dividing the attic of her house into bedrooms and converting outbuildings into studios. A private sorrow, however, was that her sister was now so gravely ill that in the fall of 1900 she had to be committed to a mental hospital. So at age 50, Florence Griswold began a new life – among artists. Though it was never stable, financially or otherwise, she would find it ever fascinating and fulfilling.

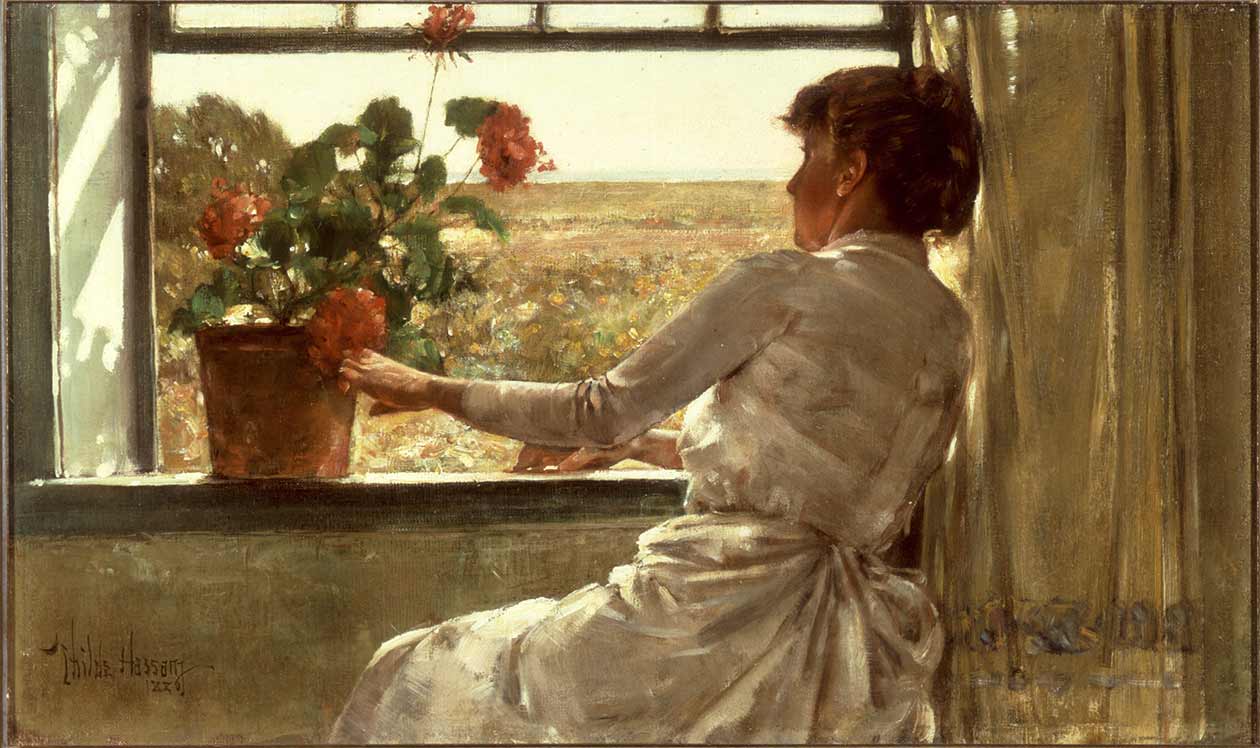

The arrival of avant-garde Impressionist Childe Hassam in 1903 and his friend Willard Metcalf in 1905 effected a change at Miss Florence’s house. A distinctly American form of French Impressionism soon dominated at Old Lyme.

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) Summer Evening, 1886, Oil on canvas, Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection & Inspection Company

Hassam was hailed, and Ranger moved on, leaving some Tonalists behind. No longer were all the artists like-minded. It was fortunate that Miss Florence had so sunny a personality, for challenges arose daily. Artists arrived with the bulky paraphernalia of their profession — canvases, easels, stools, and the white umbrellas that diffused the glare of outdoor light. The odors of paint and turpentine permeated the house, especially when bad weather forced the artists to paint indoors. Moreover, artist boarders came and went, from spring to late fall, sometimes leaving belongings for Miss Florence to pack up and send on. Some requested special bedrooms and studios, and all soon agreed that guests must win their prior approval and that no art students be allowed (although an exception was made for Woodrow Wilson’s first wife, Ellen).

Like all boardinghouses, the Griswold House operated on a schedule, although an uncommon one. Three daily meals were provided, not just dinner. Artists had to be called to lunch from whichever stream, marsh, meadow, rustic bridge, or old house they were painting; at one time a maid known as “Whistling Mary” blew a horn to alert those beyond shouting distance. Painting was often interrupted for impromptu picnics, canoeing, wagon rides, or games, which Miss Florence happily organized, pulling provisions from her larder as treats.

Dinner was in the dining room or, in hot weather, on the side porch. Meals were simple but ample: roasted meats, home-grown vegetables, pies from the orchard’s fruits. Room service was merely a kerosene lantern at night and a pitcher of water in the morning, until 1910, when electricity and plumbing were installed.

As in the liveliest of family gatherings in the era, evening activities ranged from card playing, to charades, to informal musical and theatrical performances, to the wiggle game, in which artists drew onto paper a few lines that others had to transform into caricatures. Always there was good conversation.

Woodrow Wilson was impressed by it, and the artists were stimulated by the exchange of ideas. The hospitality, the love, that Florence Griswold extended to “her boys,” as she called them, was deeply appreciated. Allen Butler Talcott described his experience in her house as having “all the charm of being a guest with the freedom of being at home.” Willard Metcalf marveled that “every day is so in line with work.” No wonder the artists called her home the “Holy House” and painted pictures on its doors and dining room walls as a lasting thank-you.