Exhibitions

Woodrow & Ellen Axson Wilson in Old Lyme

- The Museum will be closed Sunday, April 9 in observance of Easter.

This online exhibition was created in conjunction with the exhibition, The Art of First Lady Ellen Axson Wilson: American Impressionist, on view at the Florence Griswold Museum October 5, 2012 - January 27, 2013.

This exhibition is designed to enrich the Museum’s educational offerings related to Woodrow and Ellen Axson Wilson, as well as their young family’s role in Old Lyme at the Griswold Boardinghouse as part of the Lyme Art Colony. The exhibition was made possible through a grant from Connecticut Humanities.

In the midst of one of the pivotal decisions of his life…

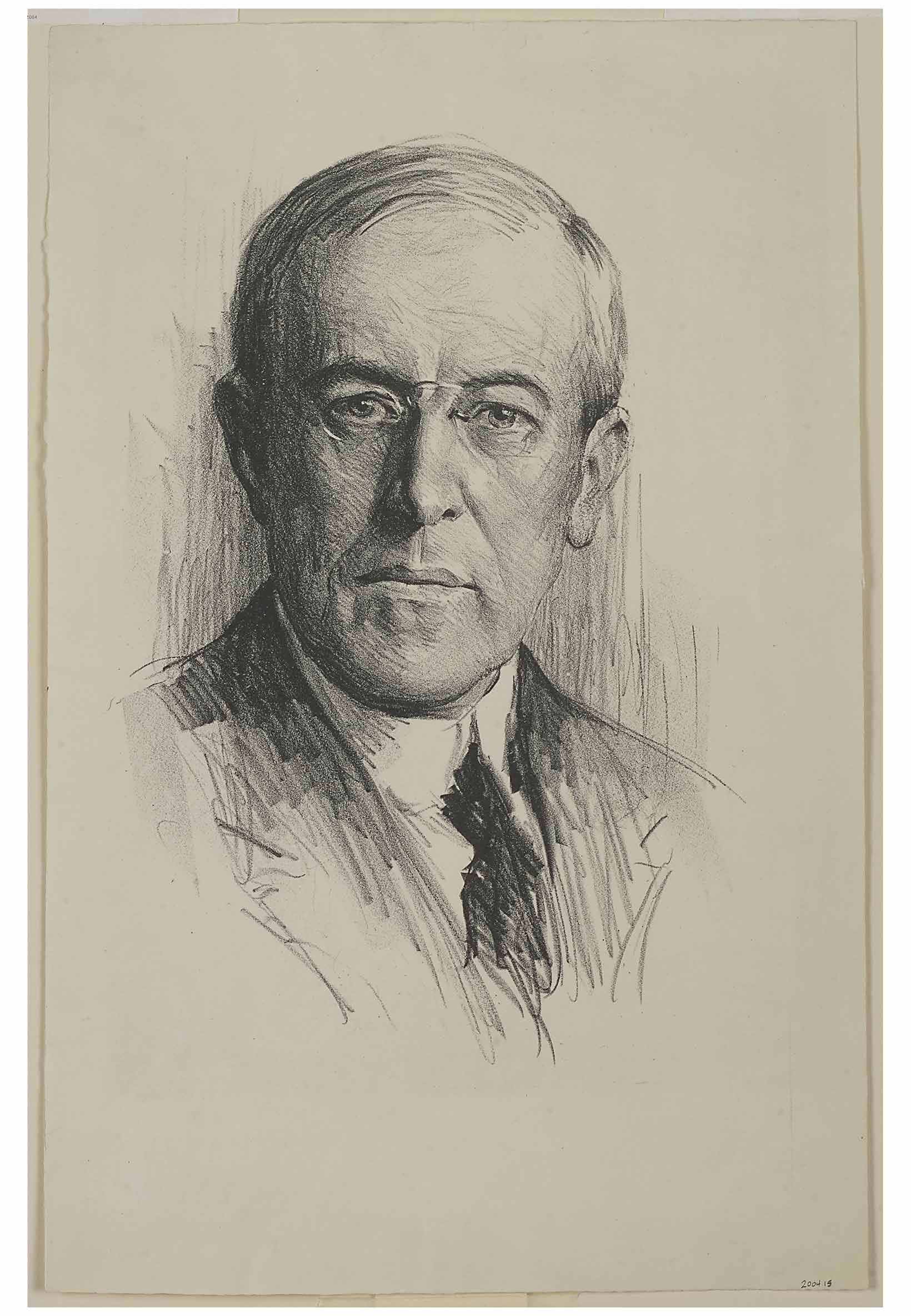

Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), then President of Princeton University, spent the summer of 1910 at the Griswold House in the company of “a jolly, irresponsible lot of artists, natives of Bohemia, who have about them the air of the broad free world.” [1] It was a place of familiarity and pleasure for Wilson and, especially, his wife, the artist Ellen Axson Wilson (1860-1914), who wanted to paint in the company of the Lyme artists and enjoy a respite from the social demands of their life at Princeton.

Throughout that June and July of 1910, Woodrow was considering whether to accept the Democratic nomination for the governorship of New Jersey. The decision was a weighty one because New Jersey was, as Wilson put it, the “mere preliminary” [2] for a larger plan.

A group of national political leaders were eager to recruit Dr. Wilson for the governorship as a means of making him a strong and popular candidate for the ensuing Presidential election in 1912, only a little more than two years hence. Ruminating on this life-changing decision, he discussed it with his wife Ellen and sought the advice of several friends and Princeton trustees to whom he was particularly close. [3]

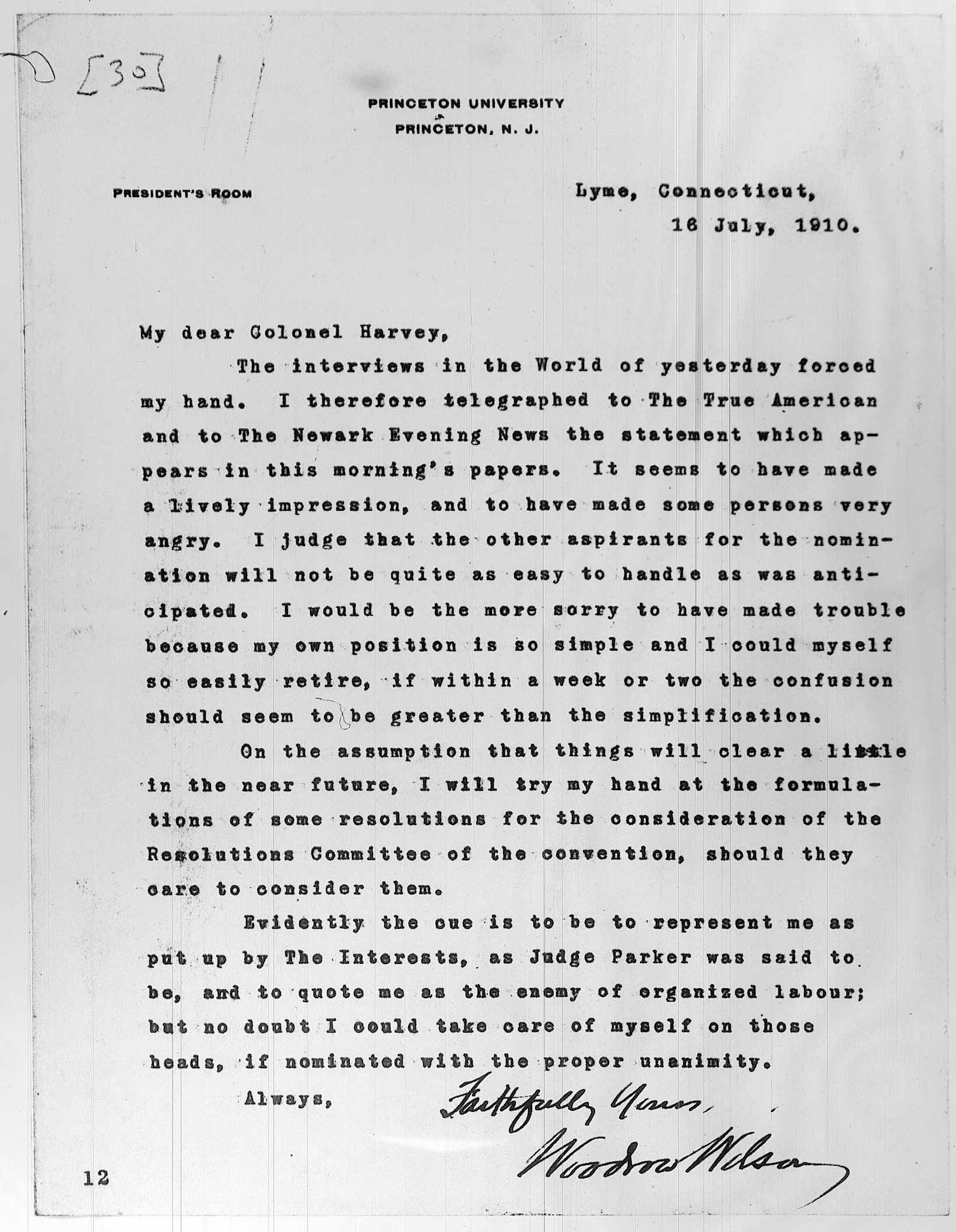

Letters, telegrams, and phone calls came daily to the Griswold House, “care of Miss Florence Griswold, Lyme, Conn.” The excitement in the household was considerable.

In early July, when news of this possibility was leaked to the press, reporters showed up to interview Dr. Wilson after a round of golf. The reporter noted that he was “collarless and perspiring and his face was bronzed.” He greeted the reporter with a smile, which darkened into a frown, however, when the subject of politics was broached. ‘I don’t want to talk politics at all,’ said Dr. Wilson, when first asked as to his possible candidacy for Governor.” [4] Within a week, however, Wilson decided he would accept the nomination on the condition that it was desired by a “decided majority of thoughtful Democrats of the State” and that it was clear he had not in any way campaigned for the office. [5] If those conditions were met, he did not see how he could forego practicing what he had long preached in his classes – the duty of public service when called upon. On July 16, 1910, Wilson released a statement to the press from the Florence Griswold House, signaling the beginning of his entry into politics. [6] In little over two years, Woodrow Wilson would rise to its highest office, becoming the 28th President of the United States.

The Wilsons’ first stay in Old Lyme – the summer of 1905 – was prompted by personal tragedy.

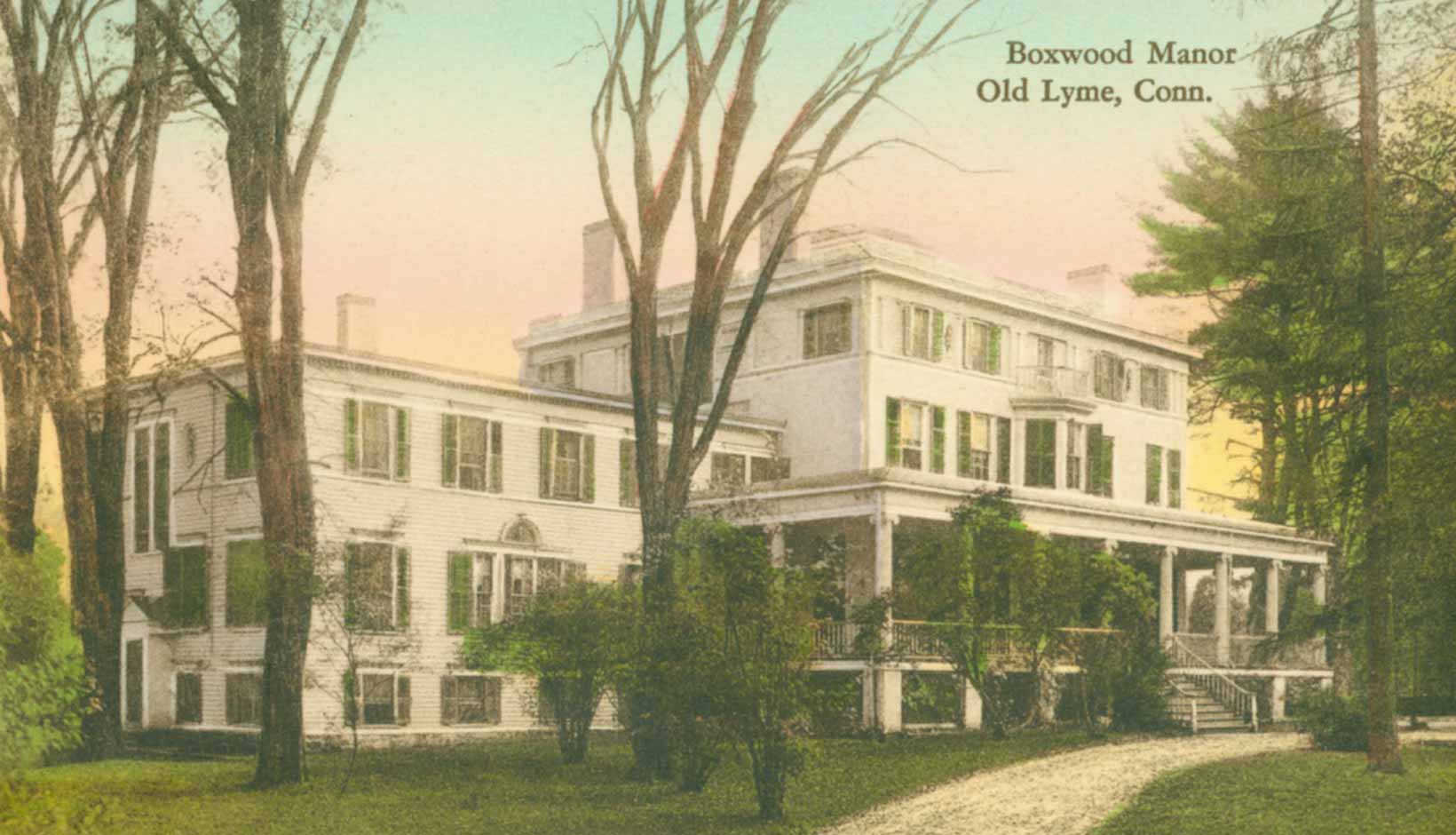

That spring Ellen’s younger brother Edward Axson (1876-1905) and his young family had all drowned in a boating accident.Ellen was devastated. Feeling that a change of scenery would be restorative for her, and at the suggestion of Princeton Professor Williamson Vreeland, the Wilsons made plans to spend the summer in Old Lyme. [7] The Vreelands had a summer place on Lord Hill in Lyme and they felt the area would be an ideal place where Ellen could pursue her interest in painting with the artists’ colony. In early July, Wilson traveled to Old Lyme to investigate the possibilities. He stayed at the Old Lyme Inn and made arrangements for the family to take their room and board at Boxwood, then a summer boardinghouse run by Miss Thibits, and just down the street from the Florence Griswold House.

Art had been long been Ellen Axson Wilson’s passion.

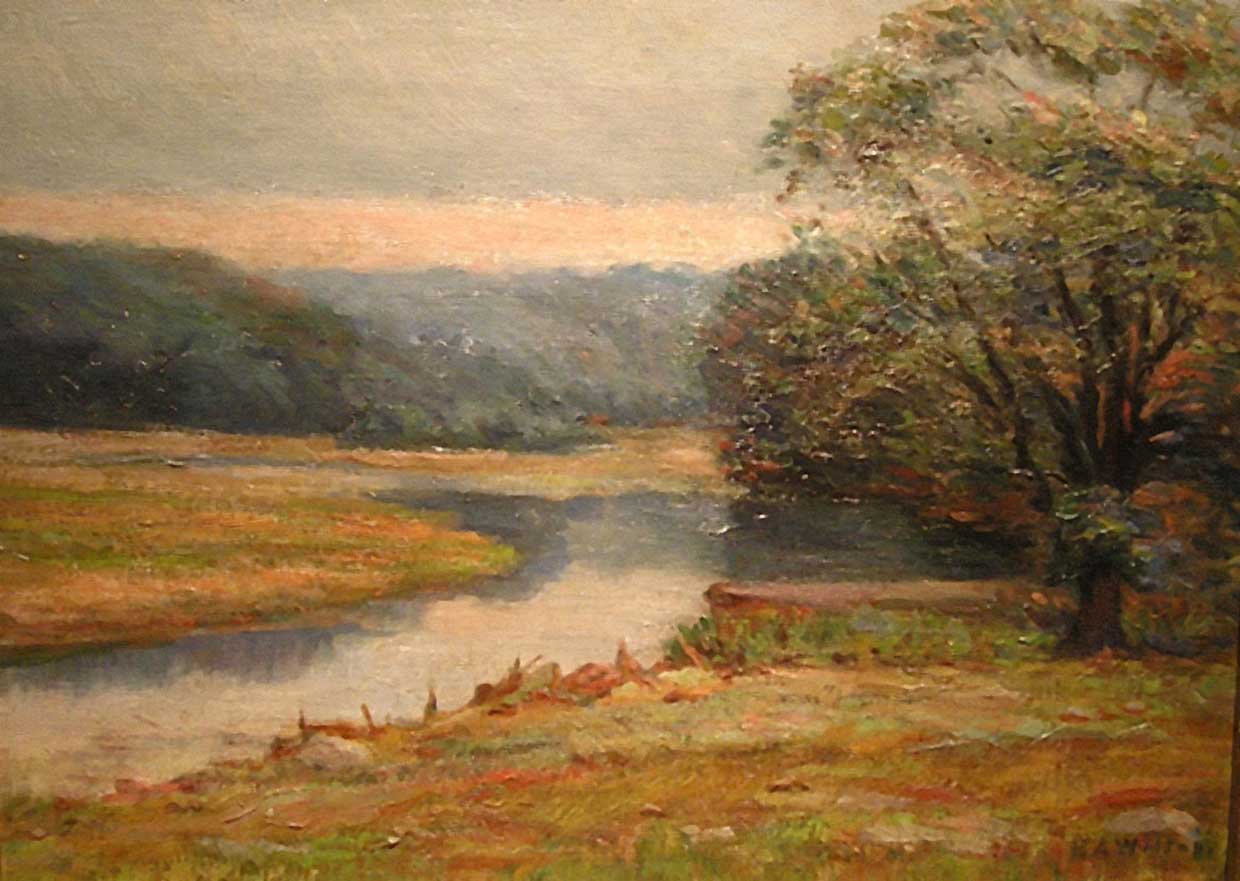

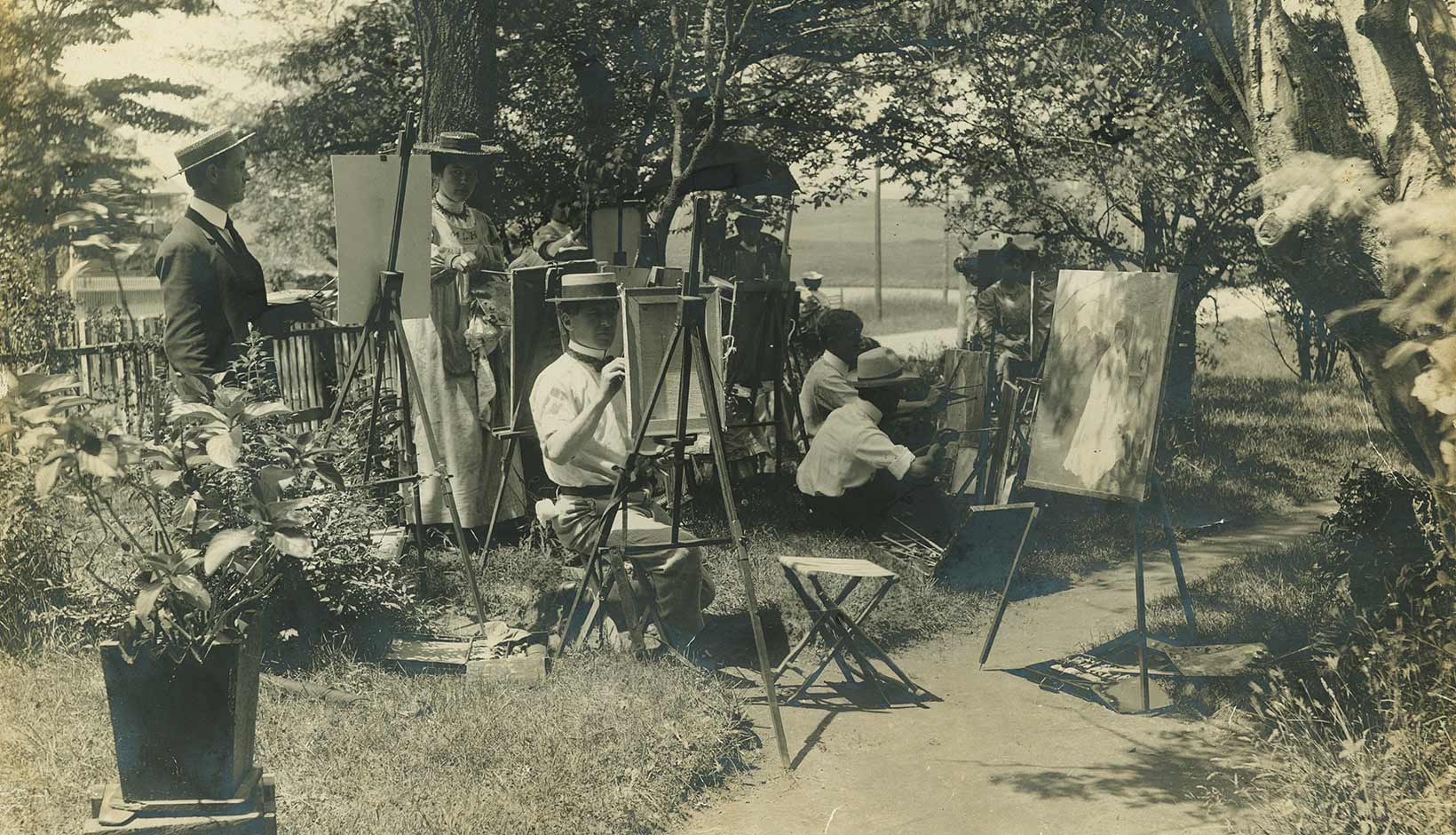

[8] Trained initially at the Rome Female College in her native state of Georgia and then at the Art Students League in New York where she spent a year from 1884 to 1885, Ellen had largely abandoned her career as an artist to raise their three daughters, Margaret, Jessie and Nell. Now that they were teenagers with their own interests, she had begun to seriously work at her art again. She enrolled in the Lyme Summer School of Art, sponsored by the Art Students League.

Normally led by the popular teacher and art colony member Frank Vincent DuMond, it was taught by his assistant Will Howe Foote during the summer of 1905. Ellen enrolled in daily classes and twice weekly critiques for a period of five weeks. According to Ellen’s biographer Frances Saunders, “Woodrow’s plan to surround Ellen with artists proved wise. She began to enjoy painting landscapes in oil, and, in due course, this would supplant her former work in portraiture.” [9] With “spirits vastly improved,” she left Old Lyme in mid-September and returned to Princeton.

During the spring of 1908, Ellen made plans to return to Old Lyme.

… but this time she sought accommodations in the Griswold House. [10]

She wrote to her daughter Jessie: “I have just learned that Mr. DuMond teaches the Lyme class this summer! Isn’t that good!”

On June 22nd, she arrived at Miss Florence’s with her three daughters and her sister Margaret “Madge” Axson. Woodrow went abroad that summer to the Lake District of England, a region he had greatly enjoyed on previous occasions. Staying in a series of rooms on the second floor of the Griswold House, Ellen threw herself into her painting and found DuMond an encouraging teacher who saw progress in her own work. He arranged for Ellen to have her own studio, an unusual accommodation for an art student in Lyme.

While the letters she wrote to Woodrow that summer have not been found...

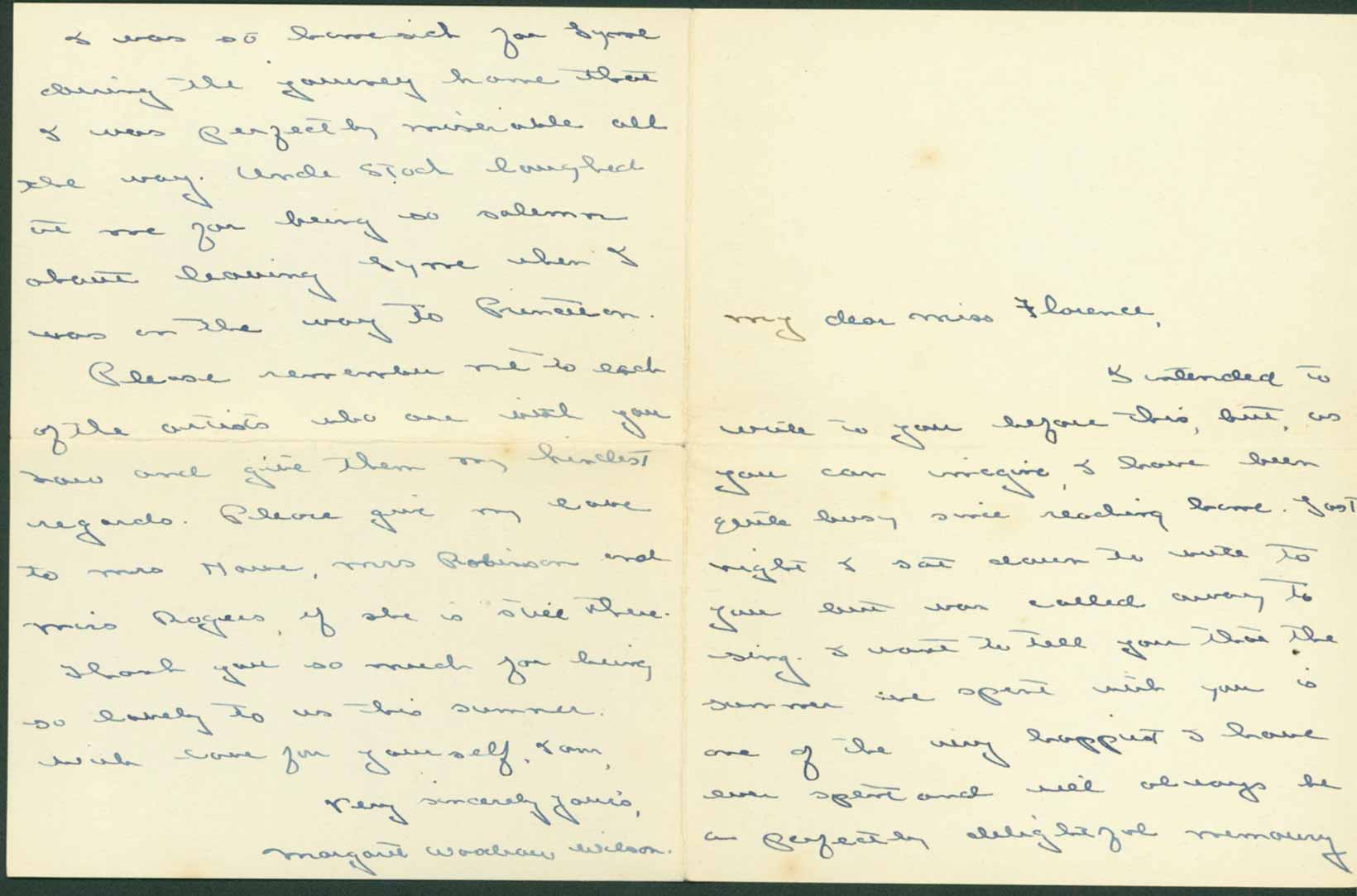

It is possible to gain a sense of her pleasure and that of her daughters at living amidst the artists. Woodrow writes of his relief that “the experiment at ‘Miss Florence’s’ [is] such a success, the situation so different from what it was at Boxwood, — your teacher so capable and direct in his method of helping, — and the outcome for you so certain and satisfactory in my mind.” [12]After returning to Princeton with ‘Mittens,’ a kitten from the house, Margaret, the oldest daughter, wrote to Florence Griswold:

“I want to tell you that the summer we spent with you is one of the happiest I have ever spent and will always be a perfectly delightful memory. The informal life at your house is just the kind that suits me down to the ground. I do hope that we shall be able to go to Lyme and to ‘the Holy House’ very often. In fact I never should go to Lyme at all unless we could stay with you.” [13]

She went on to describe her desire to return with her father: “I hope we can bring him to Lyme with us some time. I am sure he would enjoy living with the artists and eating at the hot air table.” [14]

Ellen’s interactions with the artists in Lyme continued over the winter months in New York. The sculptor Bessie Potter Vonnoh had started work in Lyme on a small bronze of the Wilsons’ middle daughter Jessie, whose beauty was noticed by the artists and others. Ellen went into the city to visit with Vonnoh and to see the finished work which she thought had “a sort of large nobility about it in spite of its size.” [15]

A few years later, Robert Vonnoh, Bessie’s husband and a respected painter also associated with the Lyme colony, would paint a large figurative oil of Ellen and her three daughters while they summered in Cornish, New Hampshire. Ellen particularly admired the work of Willard Metcalf, whose landscapes had brought such renown to Old Lyme.

She spent an afternoon in his studio in New York and came away thinking that he “outranked every other American artist.” [16]

What the artists thought of her work is less clear. In her letters, Ellen reported many positive comments. But William Chadwick remarked “although Mrs. Wilson thought that she painted well, she was not really good.” [17] Within the colony, the distinction between the art student, no matter how dedicated, and the professional artist, who relied on his or her work for a livelihood, was sharply drawn.

What the artists thought of her work is less clear. In her letters, Ellen reported many positive comments. But William Chadwick remarked “although Mrs. Wilson thought that she painted well, she was not really good.” Within the colony, the distinction between the art student, no matter how dedicated, and the professional artist, who relied on his or her work for a livelihood, was sharply drawn.

Just because Ellen Wilson was accorded the privilege of living with the artists at Miss Florence’s didn’t mean that she was one of “them.”

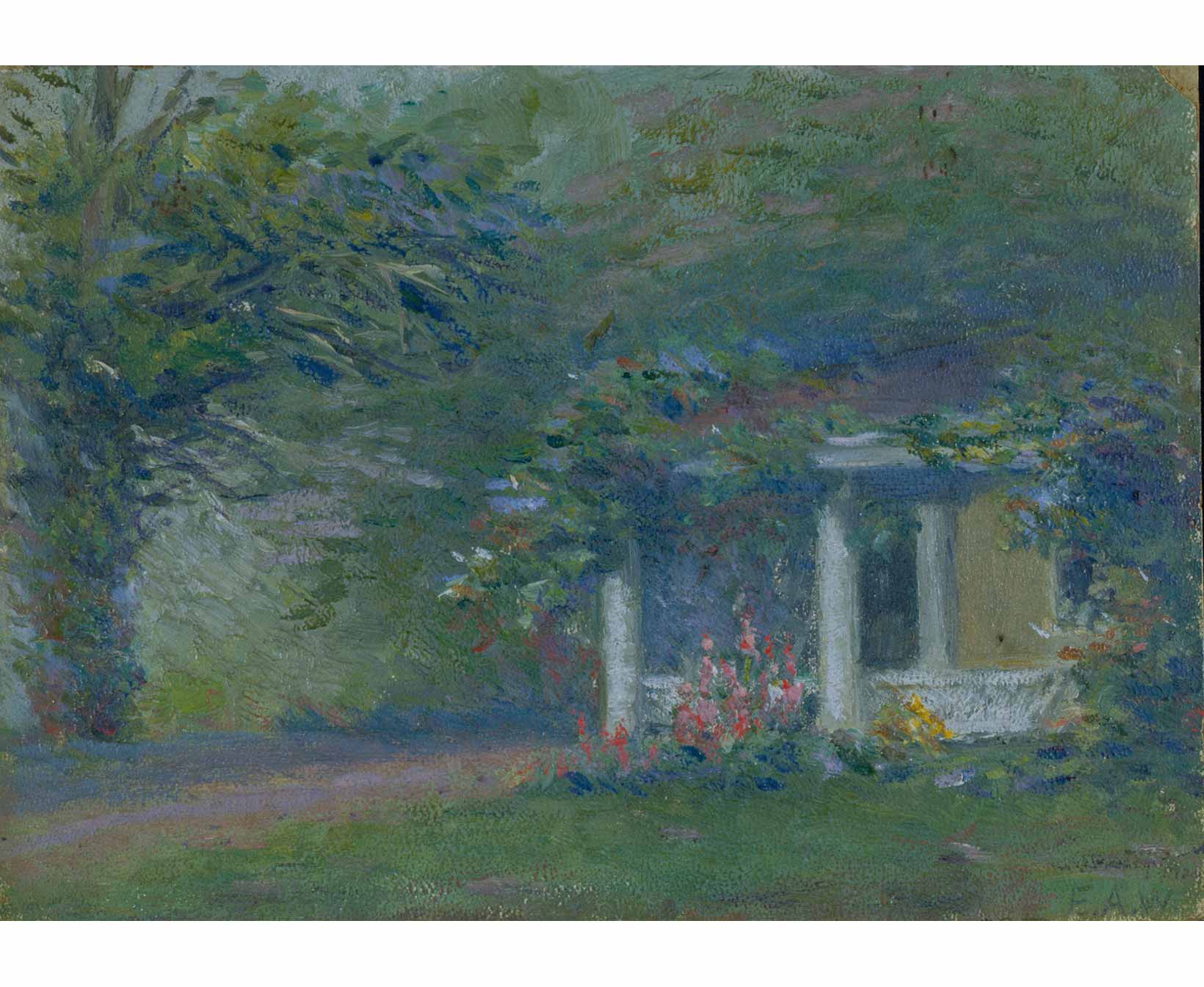

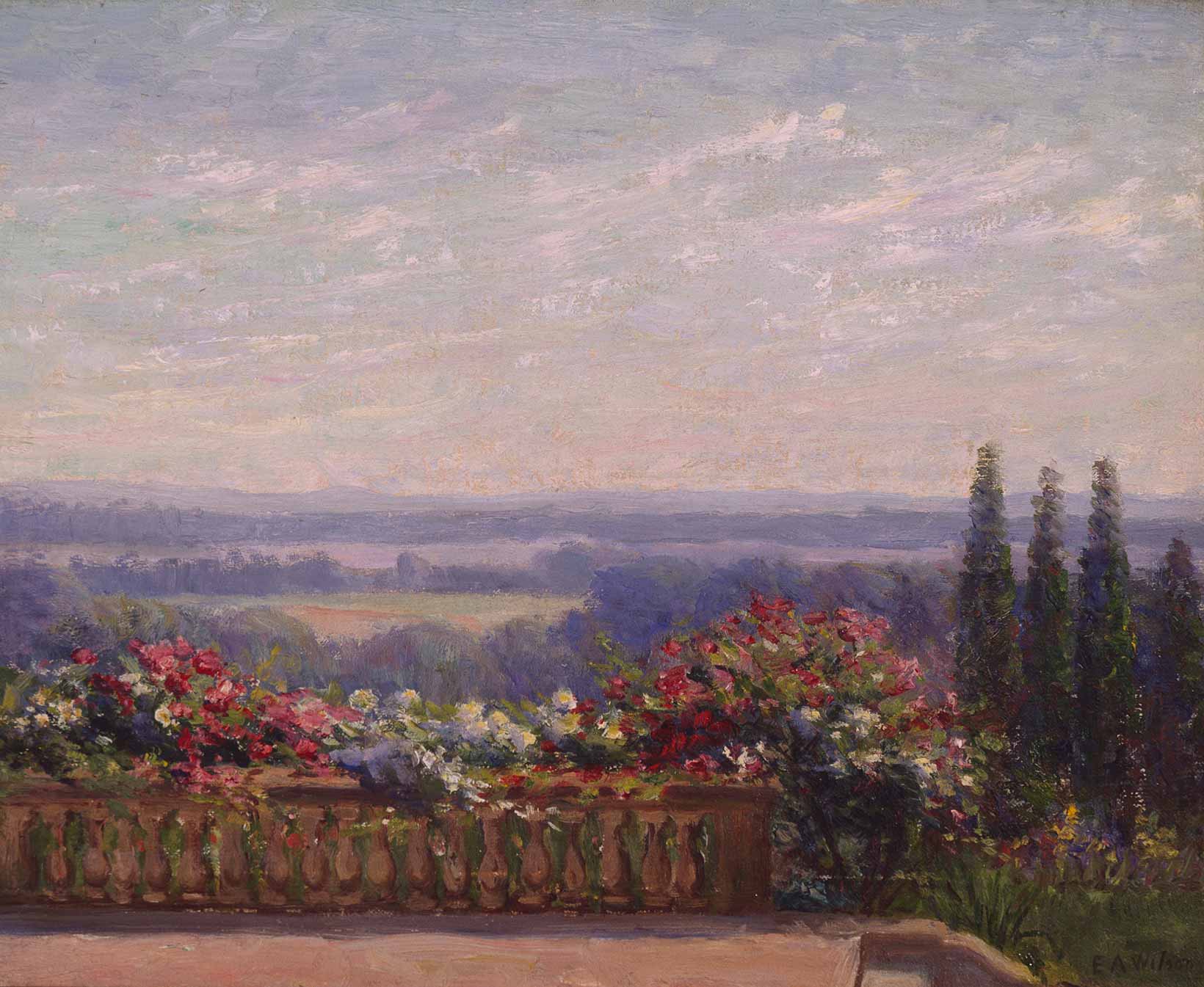

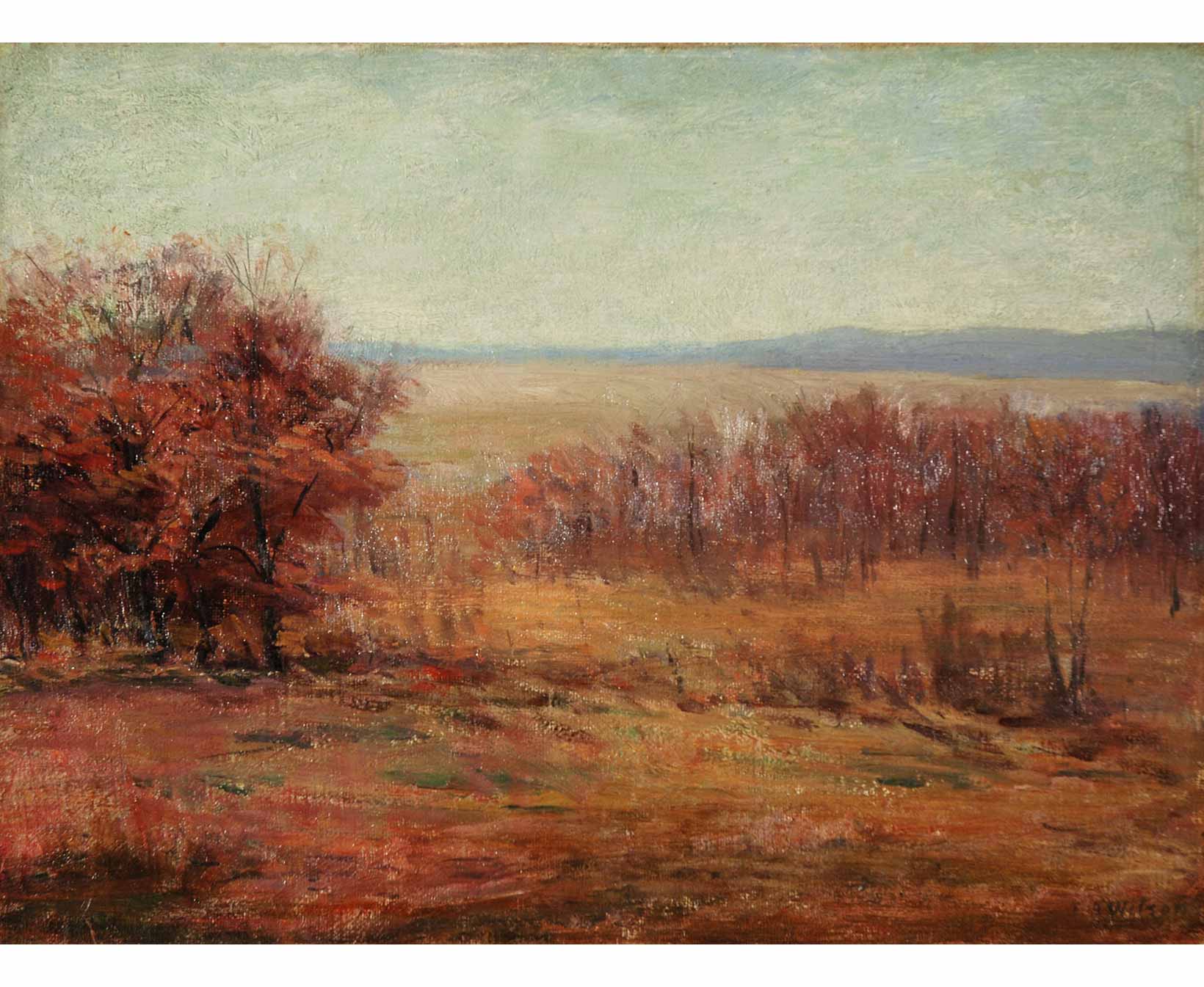

Chadwick’s judgment seems harsh today. While some of her oils have a somewhat labored quality, many of her small landscapes interpret the seasonal nuance and mood of her subject with perceptiveness and feeling. Her art was consistent with prevalent themes within the colony – rural landscapes, river views, nocturnes, apple trees in bloom, and old-fashioned gardens. She responded well to DuMond’s advice to simplify and grasp the artistic significance of nature. Her oil of “Miss Florence’s Side Porch,” which Florence Griswold owned and treasured as a memento of their friendship, captures the back ell of the Griswold House draped in verdant vines and flowers.

The painting also depicted the locale of the “hot air table” that her husband was soon to join during the summer of 1909. Leaving in mid-July, Woodrow and Ellen Wilson were accompanied by their daughter Margaret (Nell and Jessie went off to Europe) for the summer season at Miss Florence’s. While this was Woodrow’s first stay at the Griswold House, he had very likely visited during their first summer in Old Lyme in 1905 and had certainly heard much from his wife and daughters. Judging from a letter he wrote to a friend before leaving he seems to have already experienced first-hand its daily rhythms, “The Griswold’s have been great people in their time and are still decidedly gentlefolk.”

Miss Florence has taken artists (for whom Lyme is headquarters in this part of the world) in to board in her spacious old house out of mind.

The place is a perfect artistic curiosity shop, the walls and doors of one room, for example, being painted from end to end with landscapes and figures by men of all stamps, most of them now famous, who have lived there the pleasant, informal life they love and she permits.

The artists of the Lyme School regard her as their patron saint, and have all in their turns made love to her. In summer all of the meals of the singular household are taken out-of-doors on the piazza, the women at one table, the men at another, in order that they may with the less embarrassment come directly from their work to the table, dressed as they happen to be. The men’s table is known as “the hot air club,” and it I shall very appropriately join. I expect to be quite in my element in Bohemia. [18]

"They are very easy to make friends with, and I hope I am."

Lyme was a “haven” where Woodrow spent the mornings writing, the afternoons playing golf, and the evenings around the hot air table engaged in conversation with the artists. [19]

Wilson saw Lyme as a place far removed from the fast-paced world – an enclave that appealed to his scholarly, reflective nature.

“We have the sound of trains often in our ears and motor cars whirr by on the road at our door: but the world which passes by us does not notice us: we are side-tracked at a very quiet rural station where life has hardly changed its pace since the thirties [1830s]. Certainly it is the same town to a stick that I knew four years ago. I have changed much more than it has.” [20]

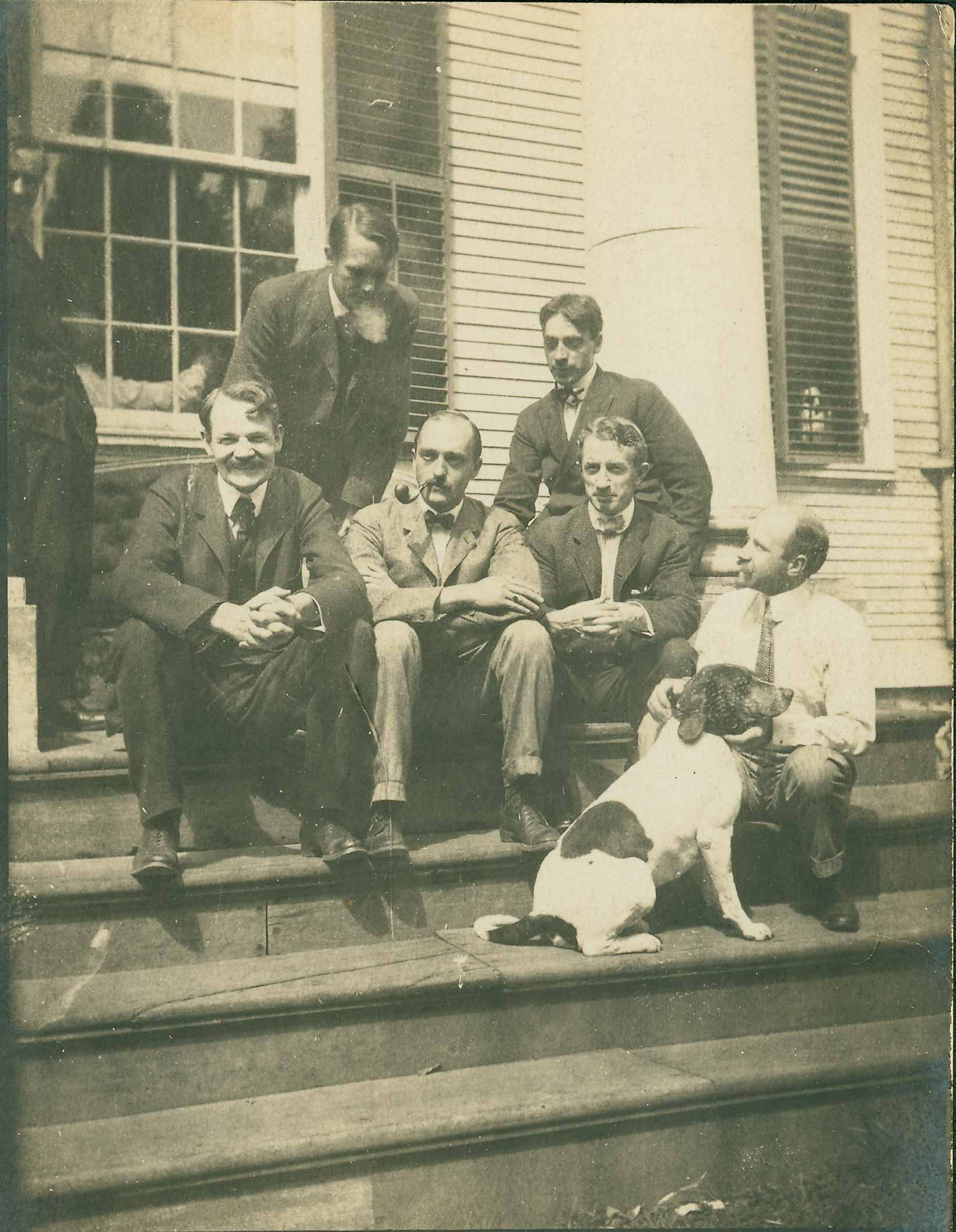

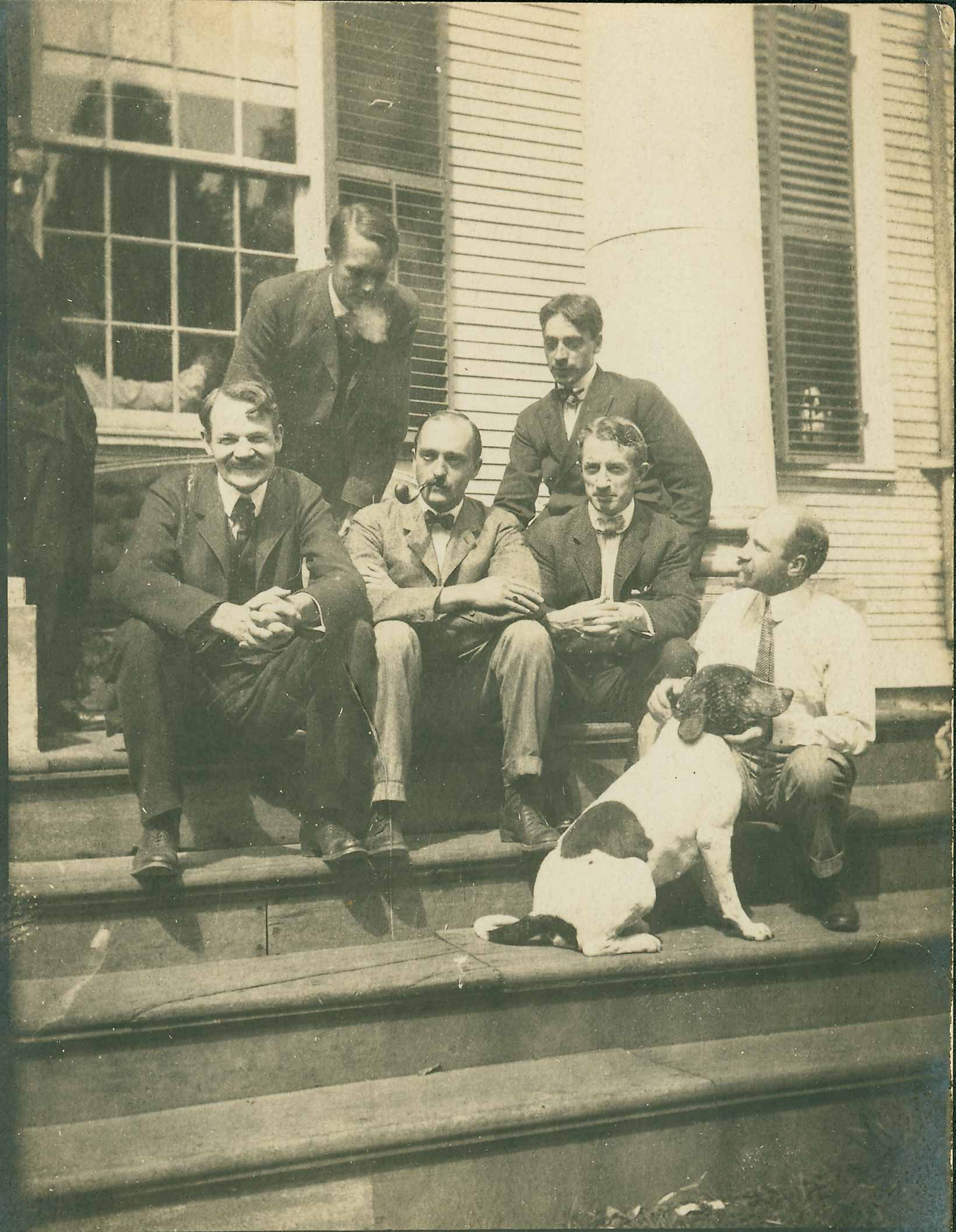

The Wilson family fit right in at Miss Florence’s boardinghouse. Ellen was encouraged by some of the artists there that summer (William Robinson, Harry Hoffman, Ernest Albert, and Frank Bicknell were among those staying there) that her work was “no longer that of an amateur” and was indeed better than “a good deal of that in the exhibitions.” [21]

Woodrow was given the title of “Colonel Wilson” [22] and, as initiation into the fraternity, was the subject of the artist’s antics. Wilson’s customary breakfast was a bowl of shredded wheat. Artist Arthur Heming “selected a nice little bunch of excelsior from a newly arrived packing case, put it in a bowl, poured cream over it, and served it to the future President of the United States.” [23]

Wilson found the colony to be a compelling experiment in communal living. As a non-artist with a somewhat detached point of view, Wilson provides us, through his letters, with some of the most detailed descriptions of life in the boardinghouse. Returning from a side trip to Philadelphia, he wrote

I find the make-up of the household here a good deal altered. People come and go. You no sooner get interested in them than they are off. It is always the interesting ones that go. The others, to whom you never give a thought and who serve as a sort of filling, are fixed and stationery, as are their counterparts in nature.

But, fortunately, even the commonplace ones are not, in this house, of the ordinary boarding house breed. It is, even in its mere ballast, an artists’ house. [24]

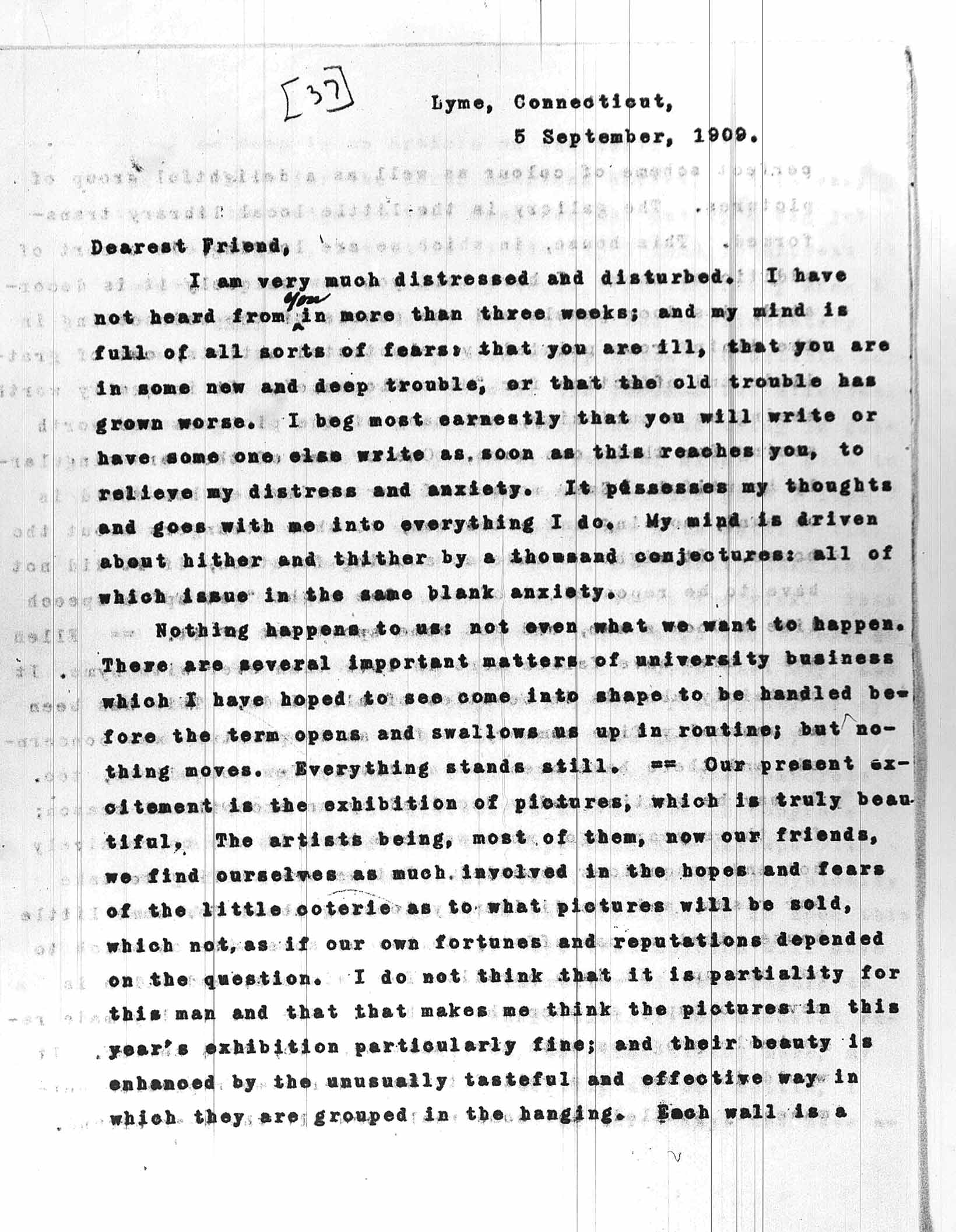

As the summer wound down in late August, the Wilson family became involved in the annual exhibition at the library. Plans and preparations for the exhibition was the subject at every meal, although once again Ellen was not invited to participate as an exhibiting member of the colony “The exhibition business is very diverting in a way,”

Like many of the artists, Woodrow and Ellen longed for a place in the country.

Their happy experience in Old Lyme led them to think seriously about buying a place there. “Ellen and I have fallen more in love than ever with Lyme,” Wilson enthused. “It certainly abounds in beauties of all kinds.” [26] Living at Princeton in the President’s residence meant they didn’t have a residence truly their own and so, late that summer of 1909, the Wilsons began “diligently looking about for some little house, that we can afford, to buy or some site on which to put one up.” [27] They eventually found a piece of property on the west side of the Lieutenant River that was owned by David P. Huntley. Everything was settled between purchaser and seller, but Huntley’s difficulties in clearing the title to the property prevented the final closing. Despite this setback, Old Lyme continued to be an important chapter in the Wilsons’ family life over the next few years.

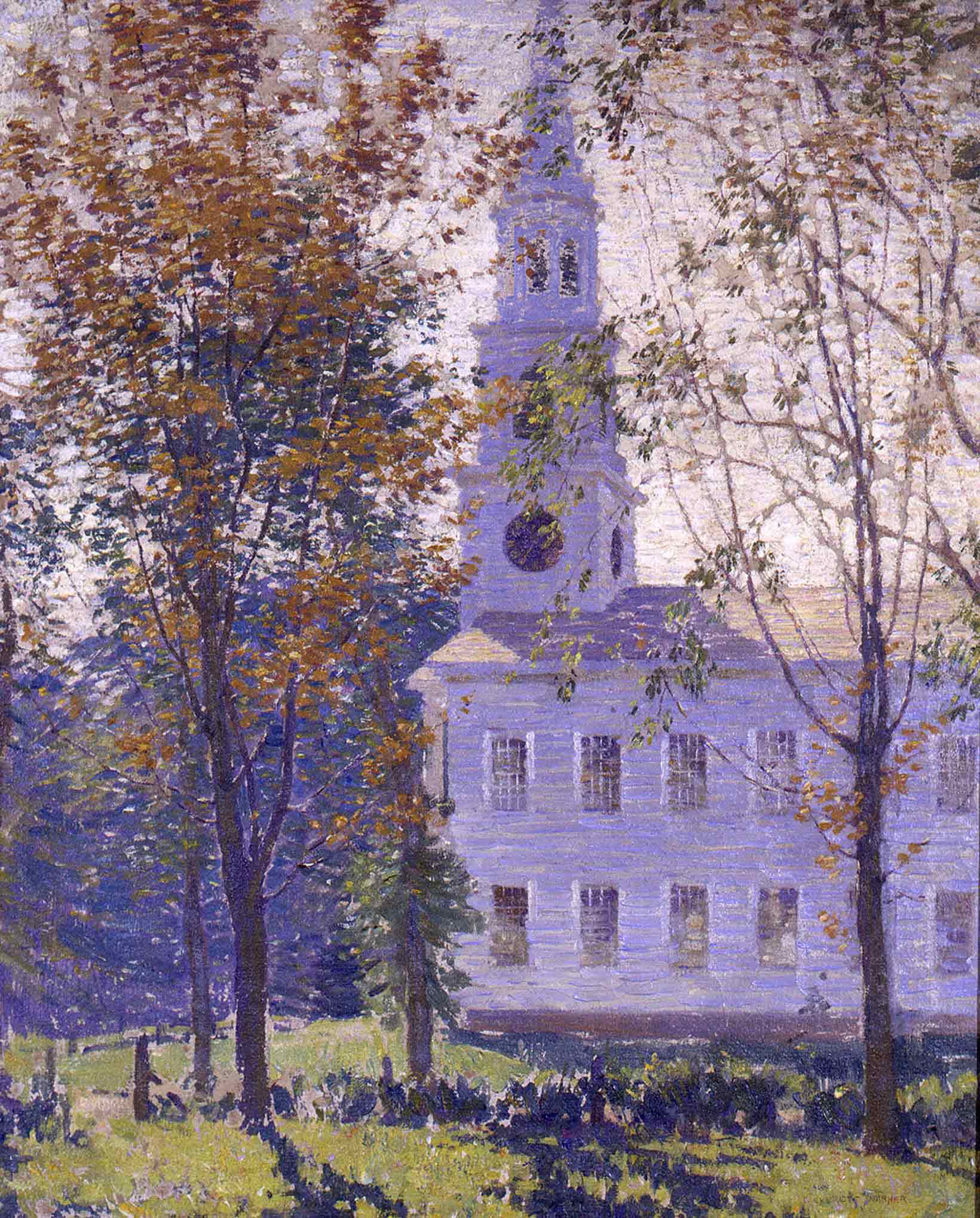

They celebrated their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary with the purchase from Macbeth Gallery in New York of a painting by the Lyme painter Chauncey Ryder. [28] Woodrow came to Old Lyme in June 1910 to give the principal address at the dedication of the rebuilt Congregational Church. His subject was “The Country Church.” He and his wife were joined that eventful summer of 1910 with an entourage that included, at various times, their daughters, Ellen’s sister Madge, and two sisters from New Orleans, Lucy and Mary Smith, who were best friends with Ellen. Not only was there excitement about Woodrow’s political overtures, but about Madge’s impending marriage to Edward Elliott, who had recently been appointed dean of faculty at Princeton. The two were married on September 8th at the Old Lyme Congregational Church in a quiet ceremony attended by the family. [29]

In May 1911, Ellen Wilson returned to Old Lyme by herself. Writing ahead to Florence Griswold, she exclaimed: “I should love to get in two weeks of sketching at that charming season.” [30] Comfortable among both old and new friends at the Griswold House, Ellen turned to painting “apple-blossom subjects” with the other artists in residence, an exercise that she reported in a letter to her husband that left “everybody swearing over them and declaring them impossible.” [31] Her daughters and the Smith sisters joined her in June, all of them in rooms at Miss Florence’s, where, by all reports, they thoroughly enjoyed the Holy House’s diversions and informal life. The artists especially regarded the daughters as good sports. [32] Woodrow Wilson came up twice during the month of June for brief visits and then, in mid-July, the entire group left for Sea Girt, New Jersey.

This was the last summer the Wilson family would spend in Old Lyme. “Mrs. Wilson and I think very, very often of our happy days with you in Lyme, and I know that Mrs. Wilson has genuinely regretted that she could not get down to the exhibition this year,” wrote President Woodrow Wilson to Florence Griswold in a letter dated September 10, 1913. [33] At the time they were making plans for a fall wedding of their daughter Jessie to Frank Sayre, a recent Harvard Law School graduate who would become assistant to President Harry A. Garfield at Williams College. The wedding took place on November 25th in the White House and Florence Griswold was one of the guests. “It was quite an event for her as she had done very little traveling,” the artist Gregory Smith recalled. [34]

The relationship between the Wilsons and Florence Griswold remained one of her most cherished friendships.

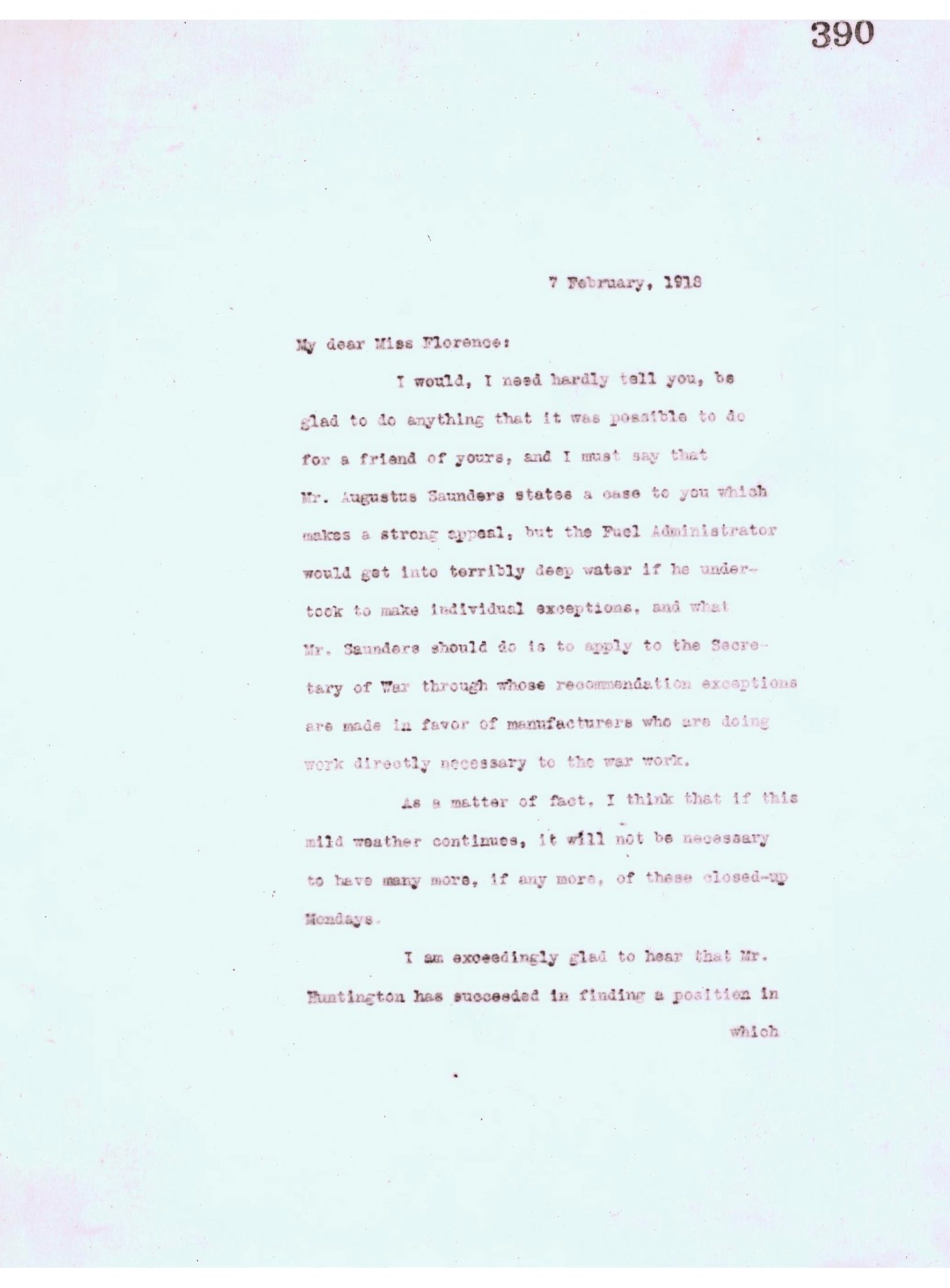

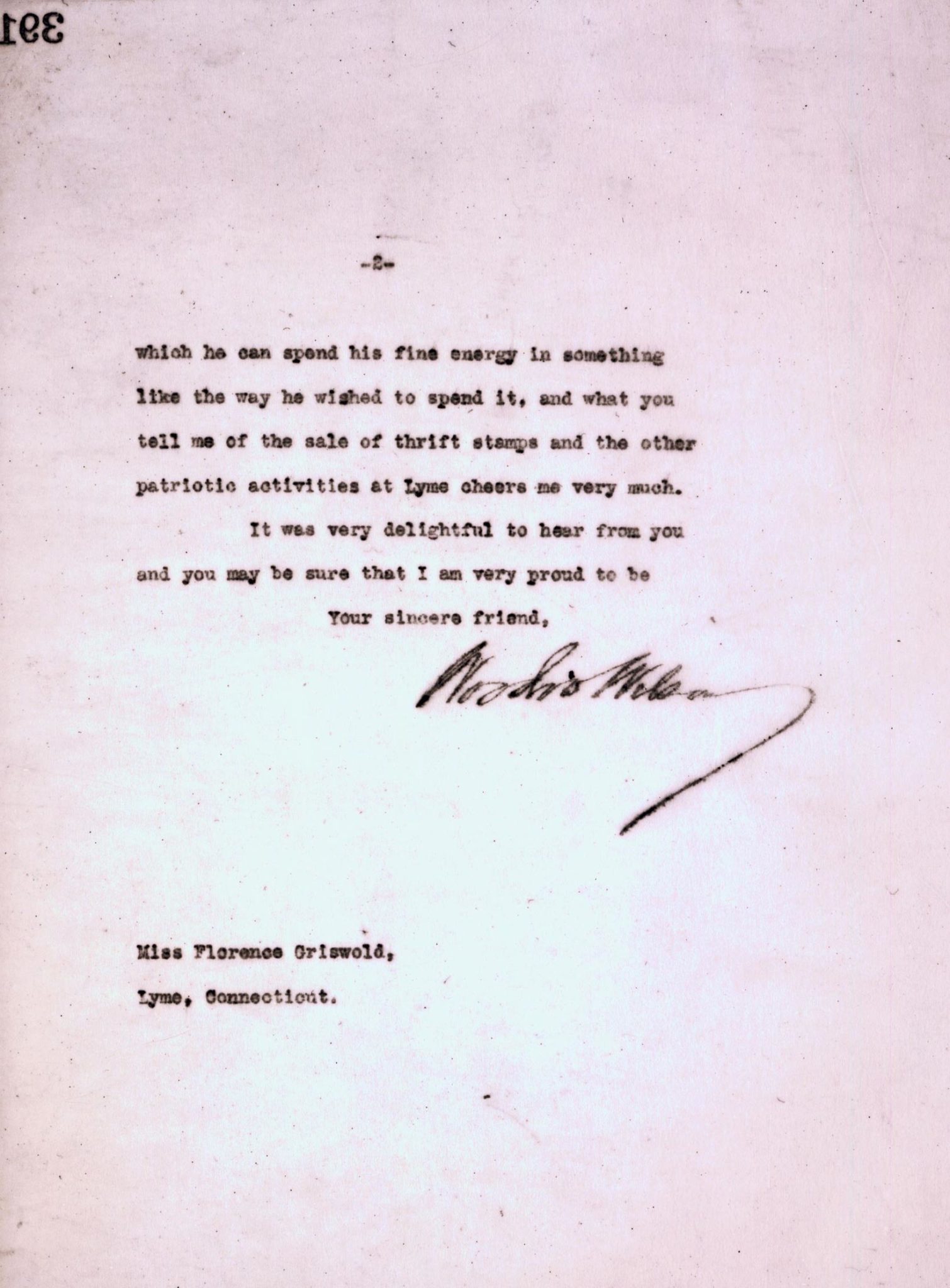

“I can’t bear to think that the Wilsons will not be here,” she wrote to Ellen in 1912, in recognition that the Governor’s campaign schedule probably wouldn’t permit a visit to Old Lyme. Even after Ellen died prematurely on August 6, 1914 in the White House, Florence Griswold maintained contact with President Wilson, frequently writing to him on largely local subjects (and often requesting that he intervene on her and the town’s behalf) that had little to do with his responsibilities as President. Nevertheless he responded patiently and with obvious fondness for her. After Woodrow remarried in December 1915, he brought his new wife Edith up to Old Lyme in September 1917 to meet Miss Florence and call upon the Vreelands.

The Presidential yacht, the U.S.S. Mayflower, anchored off Saybrook Light at the entrance to the Connecticut River. A tender brought them up the Lieutenant River and they walked through the gardens to the Griswold House. On the way back, Mrs. Wilson was overheard to comment that she did not see how anyone could stand to stay in such an “absolutely dreadful, filthy” place. The charm and informality of the Griswold House that “suits me down to the ground,” as Margaret Wilson once put it, was lost on the new Mrs. Woodrow Wilson. It would, however, not be so easily forgotten by her husband and the rest of his family.