Exhibitions

The Exacting Eye of Walker Evans

- The Museum will be closed Sunday, April 9 in observance of Easter.

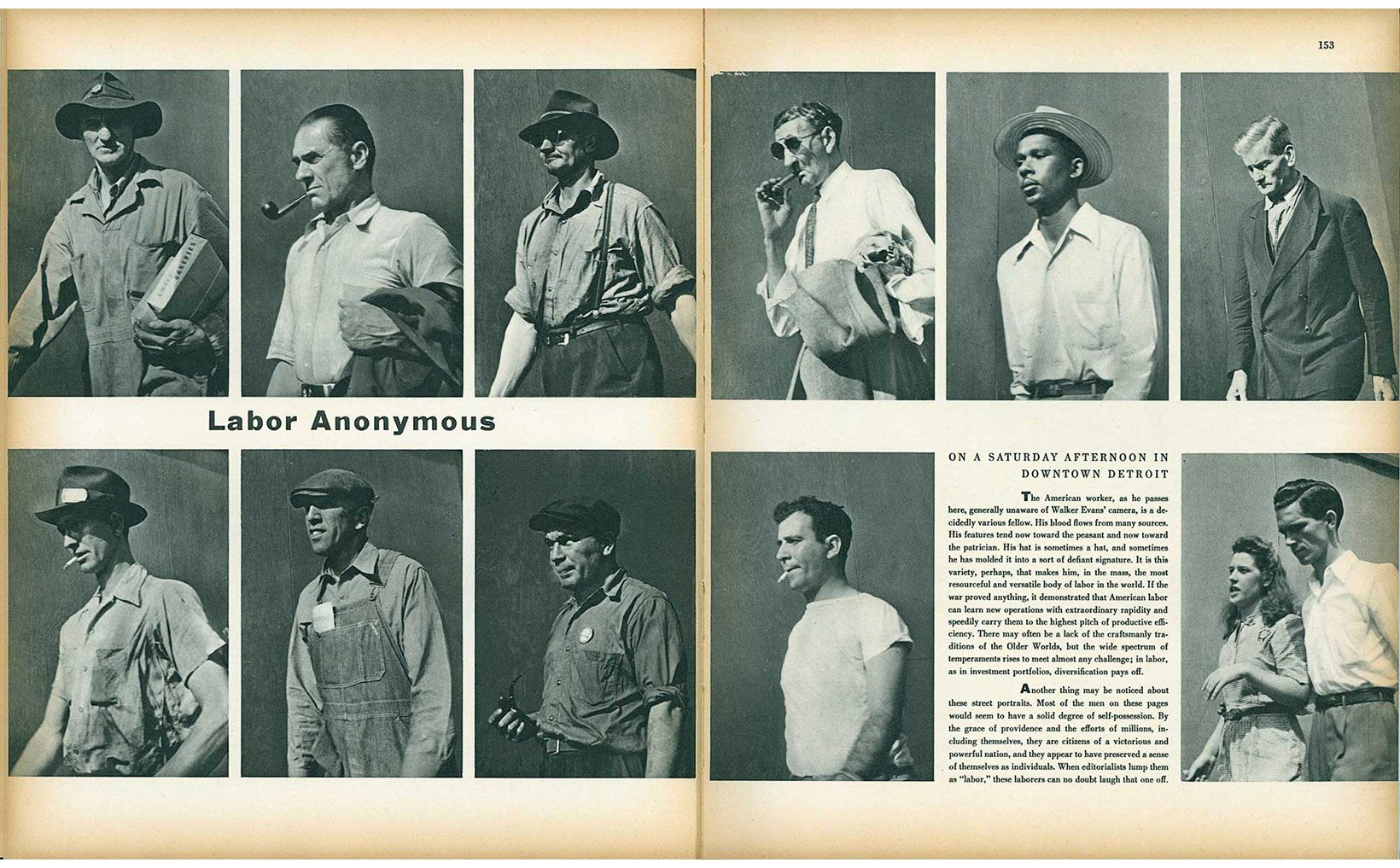

The photographer Walker Evans (1903-1975) captured a place in American social, cultural, and artistic history with his unforgettable images of the Great Depression.

This website was created in conjunction with the exhibition, The Exacting Eye of Walker Evans, on view at the Florence Griswold Museum from October 1, 2011 through January 29, 2012. Engaging with his later career, when he made his home in Lyme, Connecticut, Museum curators produced new scholarship that traced several recurring themes in Evans’ work into the 1970s, shedding new light on the photographer by examining him as creator, editor, and collector-curator. It is a part of an ongoing series of exhibitions that help to fulfill the Museum’s institutional goal of fostering an understanding of American art in all its forms.

Walker Evans, Private Collection

Joe's Auto Graveyard, Pennsylvania, 1935

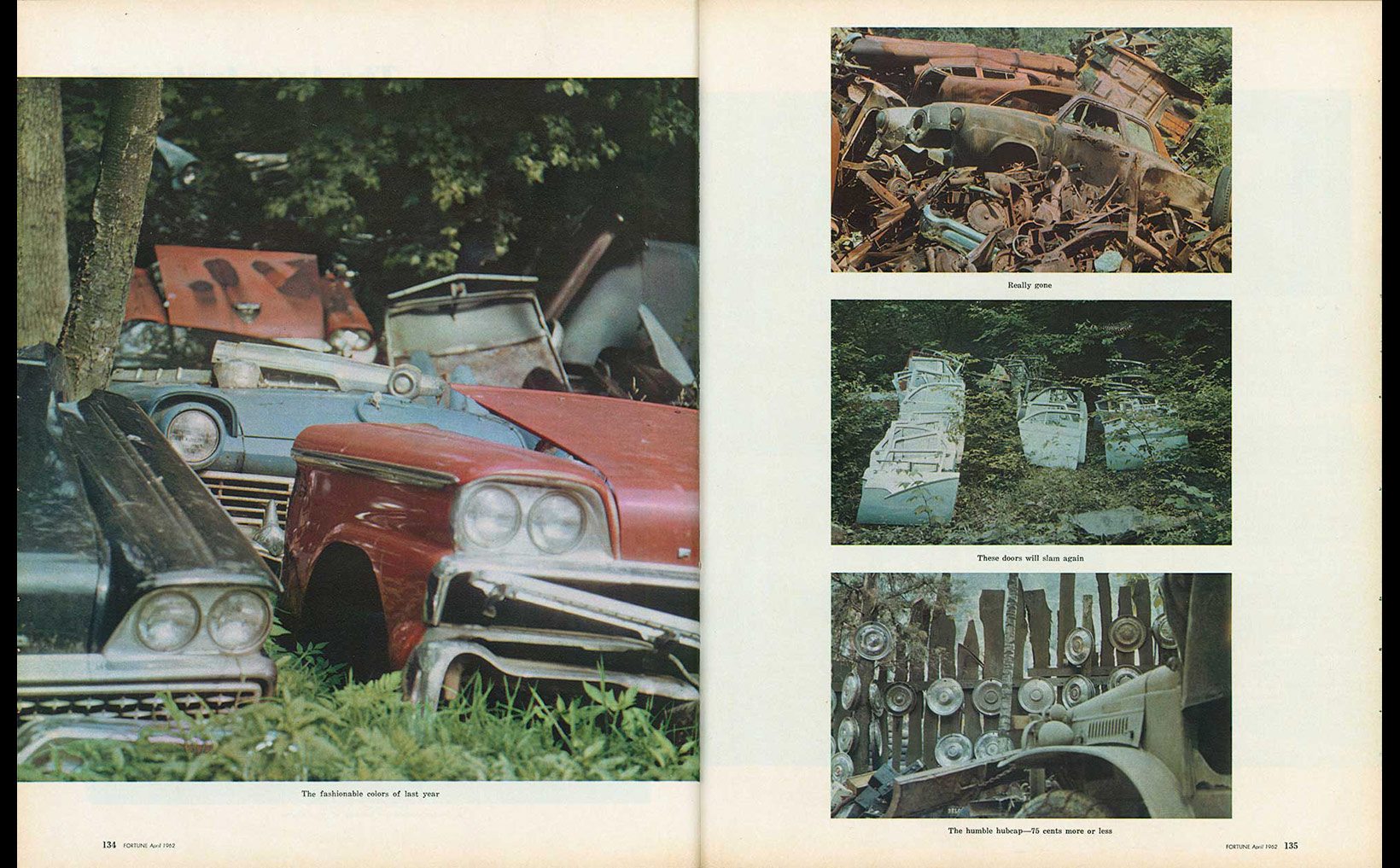

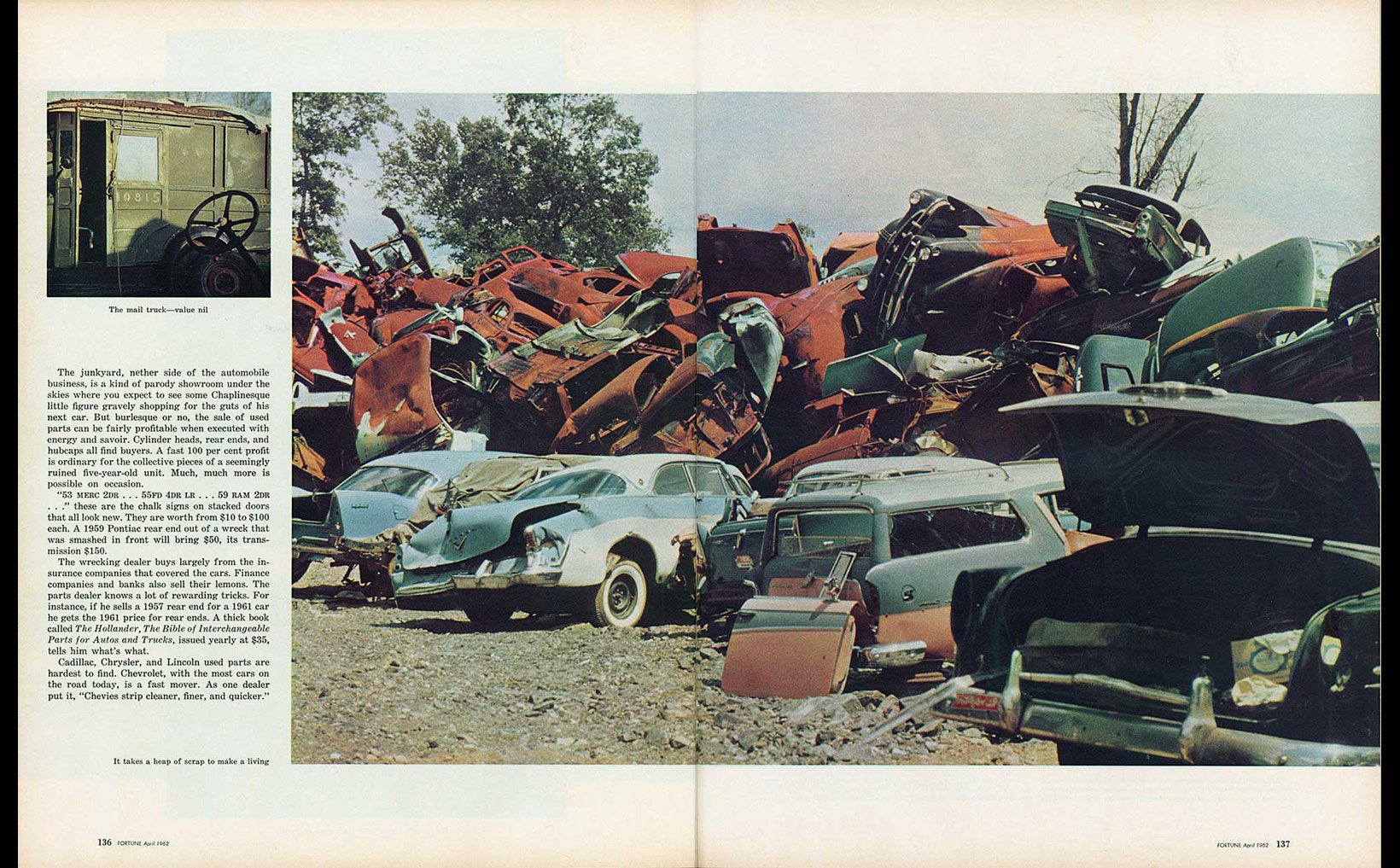

Although never explicitly a part of his directive from the Farm Security Administration, the government agency for which Walker Evans worked during the 1930s, the photographer seemingly could not resist the sight of a junked car as a symbol of the Great Depression. Here in a roadside auto dump he happened upon in rural Pennsylvania, Evans took a moment from his own road trip to capture a landscape vista of the mechanized era.

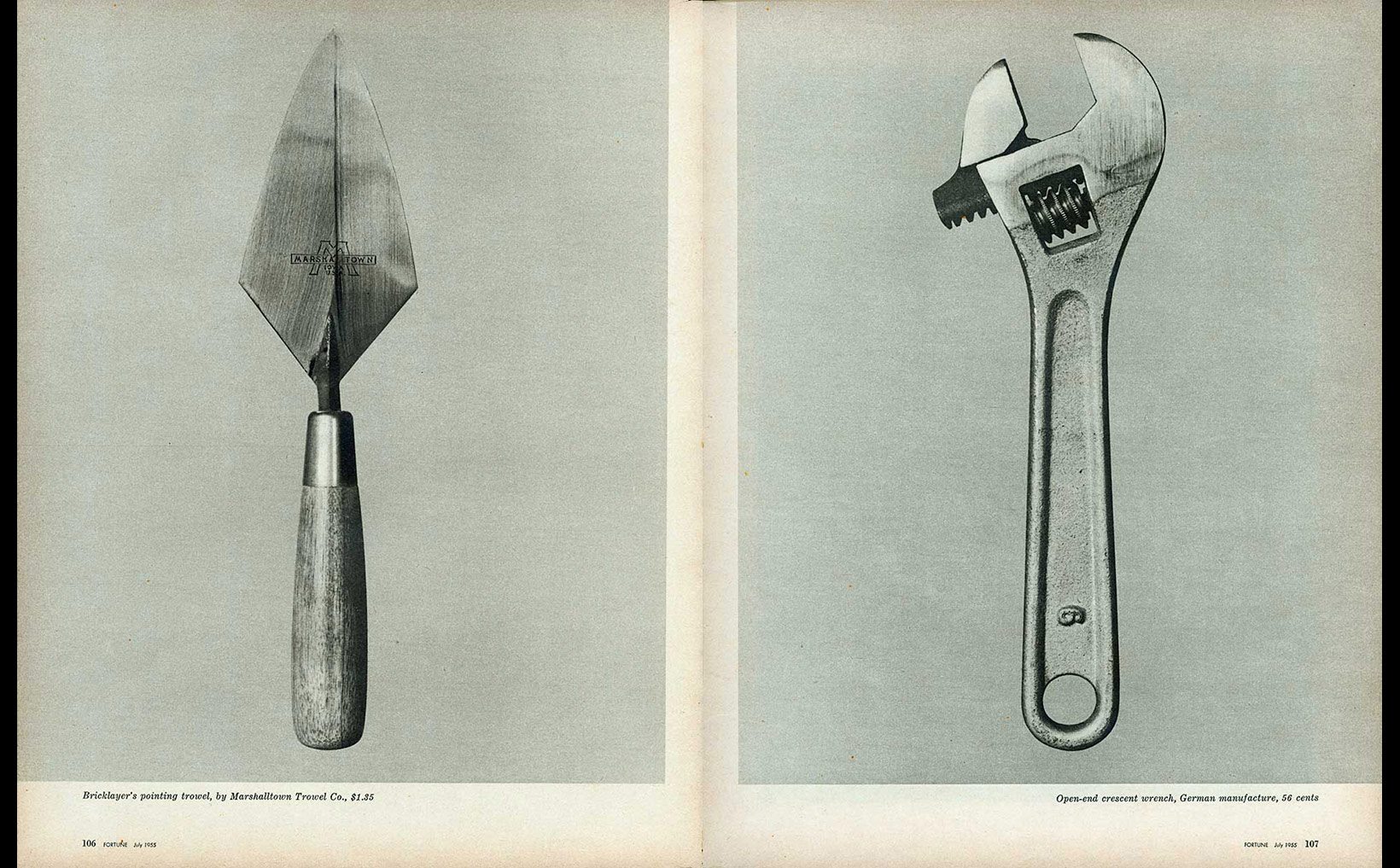

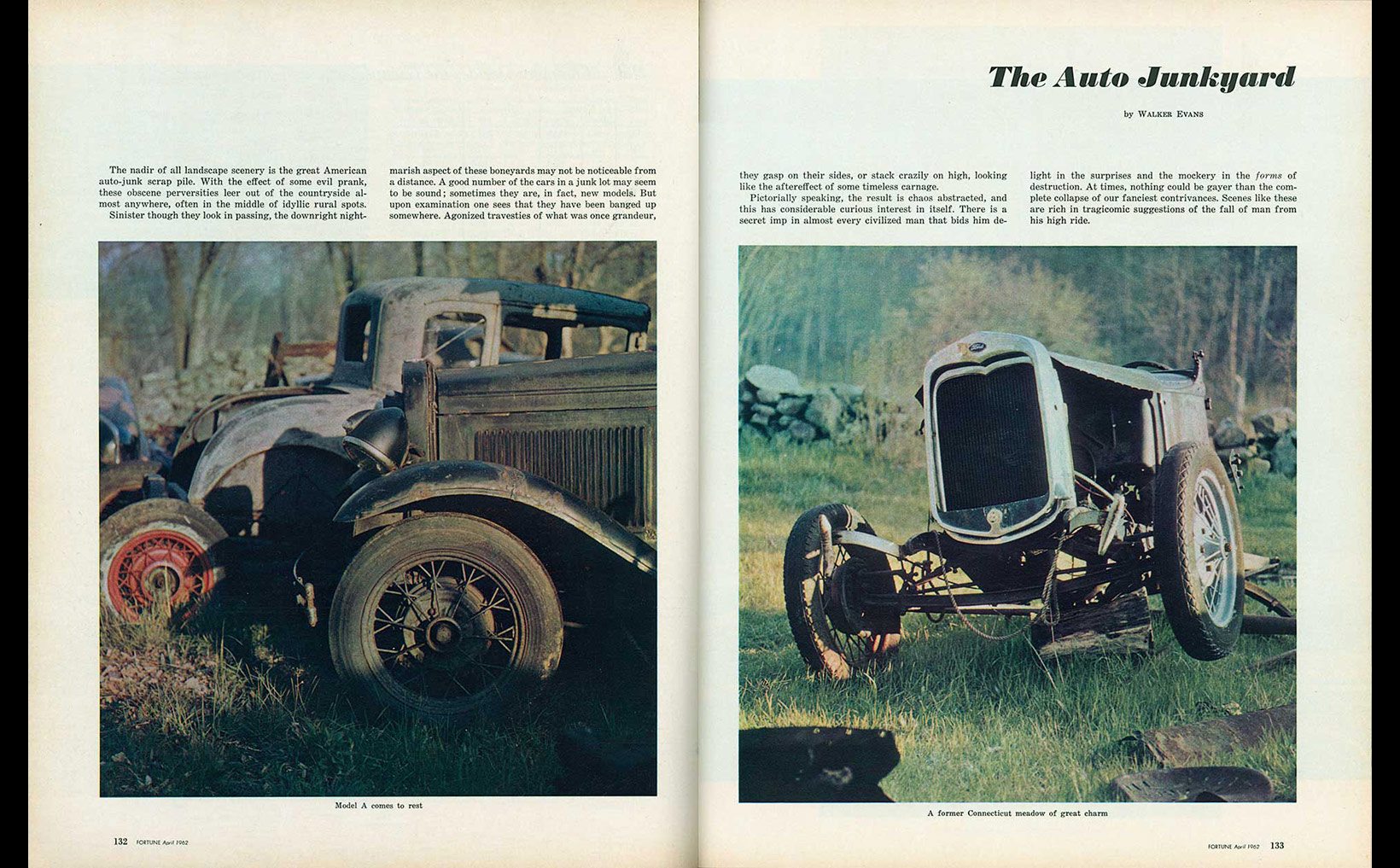

As a young man, before the Depression, Evans spent a summer working in an automobile factory, not as a matter of necessity, but as a lesson in earning money and the value of work. In 1962, reflecting on the lifespan of a car, Evans wrote for Fortune magazine of the scrap yard as a parody of the showroom. Rusted shells are scavenged and picked over in a second round of commerce, with parts swapped and sold in a process of disassembly that reversed Henry Ford’s famed production lines.

Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of the Walker Evans Estate ©Walker Evans Archive, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Chris Voorhees' Junkyard, Lyme, CT, ca. 1962

The remnants of this Model A Ford sat in a junkyard adjacent to Walker Evans’ home in Lyme, Connecticut, for decades. He captured this portrait of decay, reminiscent of the field full of junked cars he famously photographed in Pennsylvania in 1935, for a 1962 Fortune magazine photo essay using both black and white and color film. The color photo appeared in the magazine, with the caption “A former Connecticut meadow of great charm.” In the early 1970s, Evans reexamined the neighboring junkyard, this time with a Polaroid SX-70, one of a very select number of subjects he re-visited over his career.

His persistent appreciation of subjects others found too ordinary came to be one of the hallmarks of the photographer’s career. “Most people would look at those things,” Evans recounted, “and say, ‘Well, that’s nothing. What did you do that for? That’s just a wreck of a car or a wreck of a man. That’s nothing. That isn’t art.’ They don’t say that anymore.”

Walker Evans, Private Collection

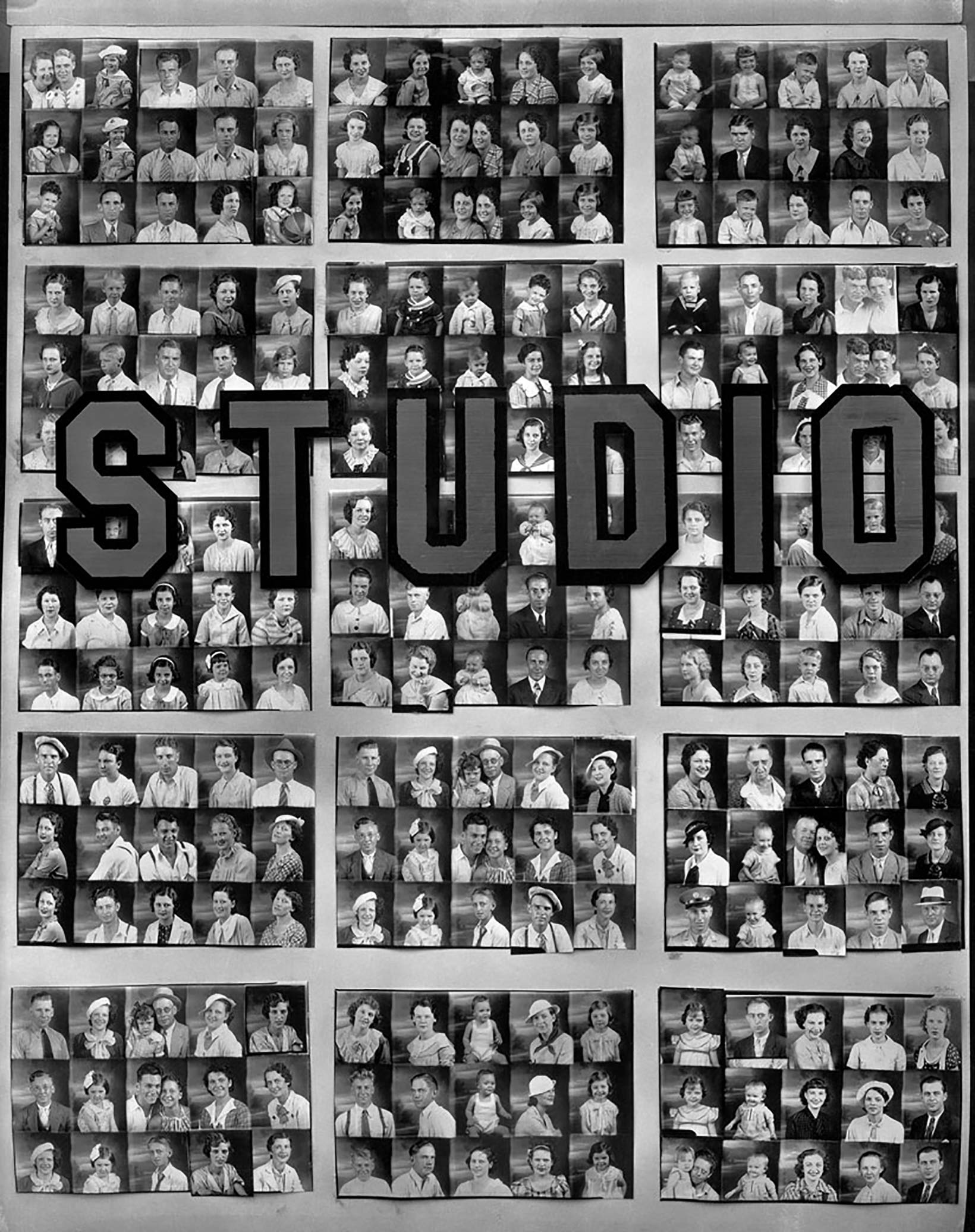

Penny Picture Display, Savannah, 1936

One of the benefits of working for the FSA during the Depression was the loan of an 8×10 Deardorff view camera, which Walker Evans used to capture this image of a photographer’s window display in Savannah, Georgia. On the market from 1923 through 1988, these large format cameras were loaded with individual film sheets, good for a single exposure. With its various moving parts and extensions, the camera offered the greatest control for professional photographers in creating their images. Evans sent his 8×10 negatives in individual envelopes inscribed with technical information about the shot back to the FSA headquarters in Washington, D.C., where they were later printed.

In Penny Picture Display, Evans discovers a kind of anonymous portraiture in the way that he makes this photograph of other photographs, or, in this case, many photos. In just a few years he would set about surreptitiously capturing anonymous portraits on the subway in New York with a concealed handheld camera, a project that could not be accomplished with a massive view camera used here.

Walker Evans, Private Collection

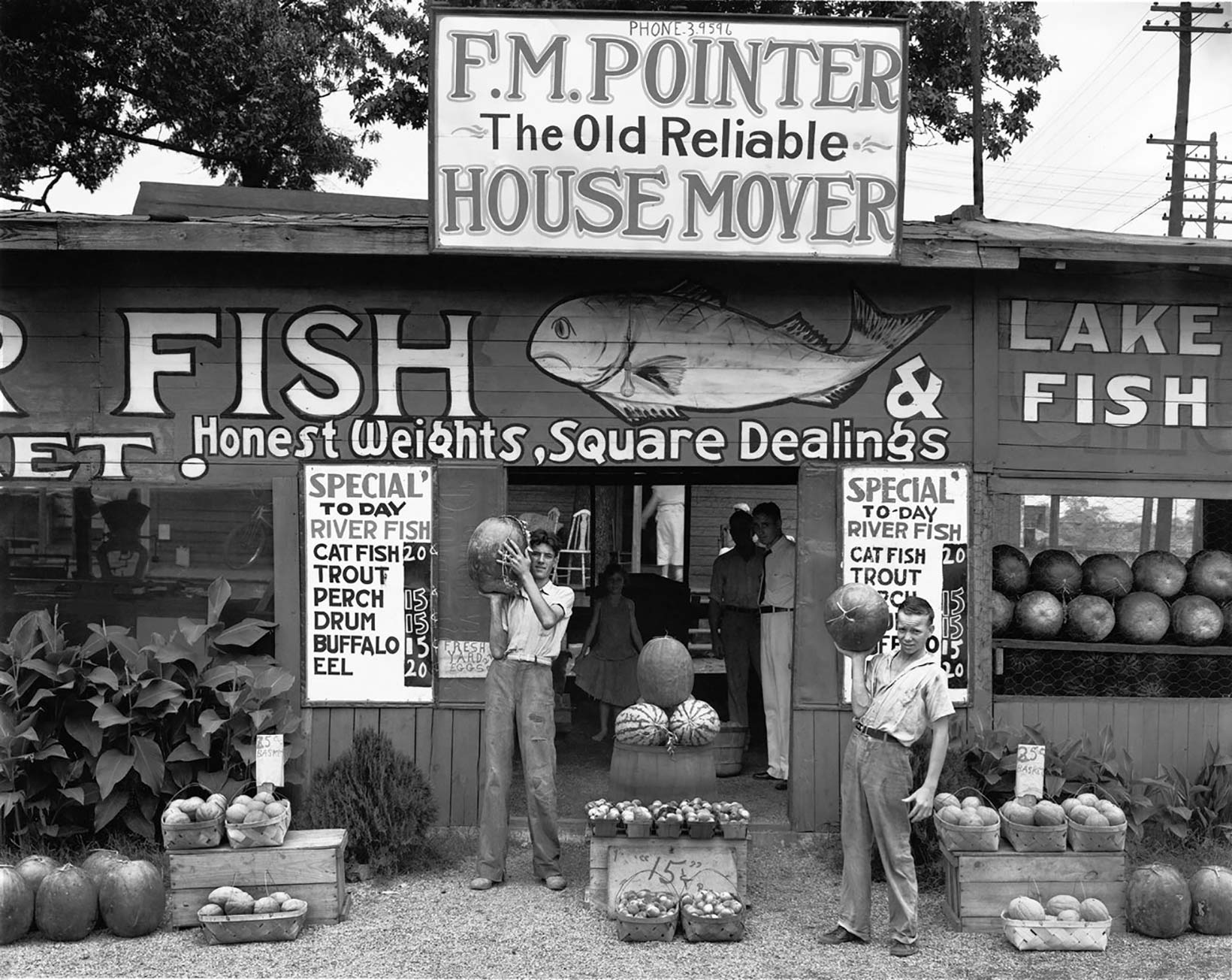

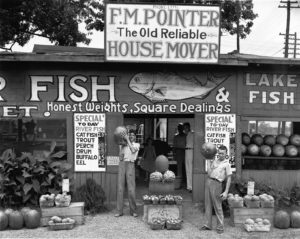

Roadside Stand Near Birmingham, 1936

“I think in truth I’d like to be a letterer,” Walker Evans reflected in a 1971 interview, when he was a faculty member in graphic design at Yale. By that point his fascination with signs had mingled with his passion for collecting; instead of simply photographing signs—collecting their images—he was decorating his Lyme home with them. Many years before, when Evans was a boy, his father was a copywriter for an advertising agency, a field Evans acknowledged as a new “American profession.”

In this example of a roadside farm stand, the building is virtually lost in the signage announcing what is on offer. Even the melons stacked and hoisted out front serve as a kind of non-verbal sign. In other images of signs Evans seems more amused by ironic meanings and double entendres or the abstract shape made by letters and partial letterforms. Here, the message is as straightforward and honest as the services being advertised.

Walker Evans, Private Collection

Butcher Sign, Mississippi, 1936

Walker Evans’ attraction to advertising and signs was a logical progression throughout his career. Instinctually drawn to strong visual imagery, he developed his eye as a young man, working in the map room at the New York Public Library. Stimulated by more than just interesting type and clever wordplay, he later fixed on how an image alone could convey meaning. Its text long faded, this sign relies upon the hand painted bull to advertise the butcher shop. Signs, Evans thought, offered “infinite possibilities both decorative in itself and as popular art, as folk art, and also as symbolism… It’s a very rich field.”

The artistic endeavors of country sign painters intrigued Evans. He frequently captured with his camera the naïvely painted chickens, pigs, and cows of butcher shop signs. In his later years, Evans took up the brush himself, working in a kindred flat, folksy style.

He even displayed his paintings in a local exhibition in Stonington, Connecticut, in 1961. One of the works from that exhibition is now in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Walker Evans, Private Collection

Garage in Southern City Outskirts, 1936

In contrast to so many of his straight-on views of buildings and uninhabited streets, a small drama plays out in the tableau of Garage in Southern City Outskirts. Evans managed to capture the scene relatively anonymously from a vantage point across the street. Inside the garage a woman in a fur coat looks with concern at the work the man opposite her is bending down to accomplish. Judging from her attire, it is an unplanned trip to the mechanic.

Waiting outside, another woman stands with the twisting pose of a Botticelli Venus, a classical beauty among the spare tires. Back inside the garage, a boy, perhaps a shop assistant, spies Evans at work across the street, regarding him with mild curiosity. The extreme detail captured by Evans’ 8×10 view camera even records a man in the distance on the other side of the building, his face visible through the windows of the car in the garage.

Walker Evans, Private Collection

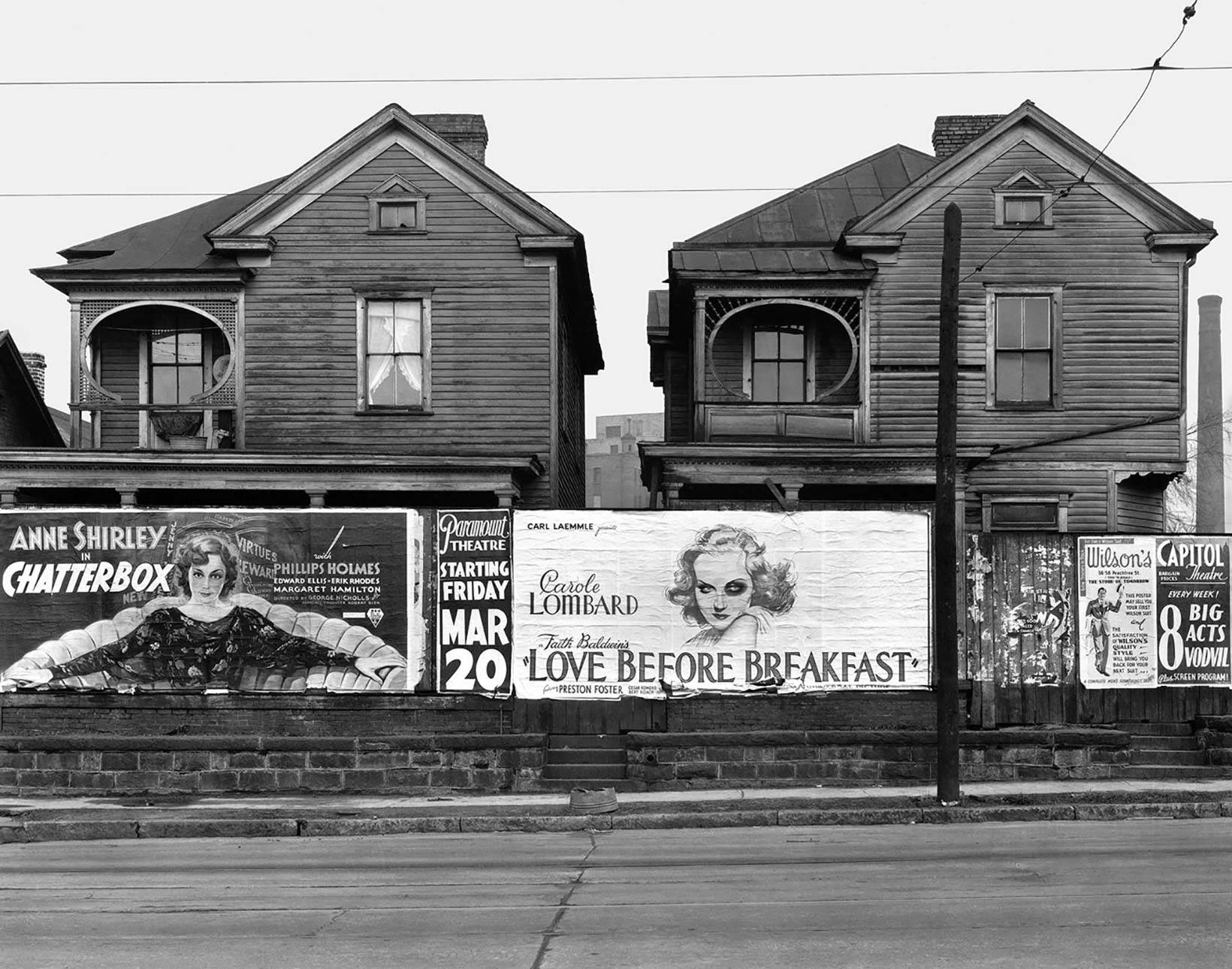

Houses and Billboards, Atlanta, 1936

On March 23, 1937, Evans was cut from the Farm Security Administration, ending his contract with the government, and his bi-weekly checks of $120. The government owned the rights to his photographs including House and Billboards, Atlanta. The image later appeared in Land of the Free, a 1938 book by Archibald MacLeish, without Evans’ prior knowledge. The accompanying poem about rural decay seemed mismatched with Evans’ photo of two walled up Victorian homes in the heart of Atlanta.

The oval porch decorations on the houses visually rhyme with the eyes of Anne Shirley and Carole Lombard pictured on the billboards. As if to blur the boundaries between art, popular culture, and life, Evans frequently incorporated movie posters into his imagery over the course of his career. In 1932 Cuba, where he befriended Ernest Hemingway, Evans’ captured a street scene that included a poster for the film version of A Farewell to Arms.

In Bridgeport, Connecticut, he photographed a movie poster for Tobacco Road, a 1933 novel about poor tenant farmers of rural Georgia, adapted into 1941’s comedic film version directed by John Ford.

Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of the Walker Evans Estate ©Walker Evans Archive, Metropolitan Museum of Art

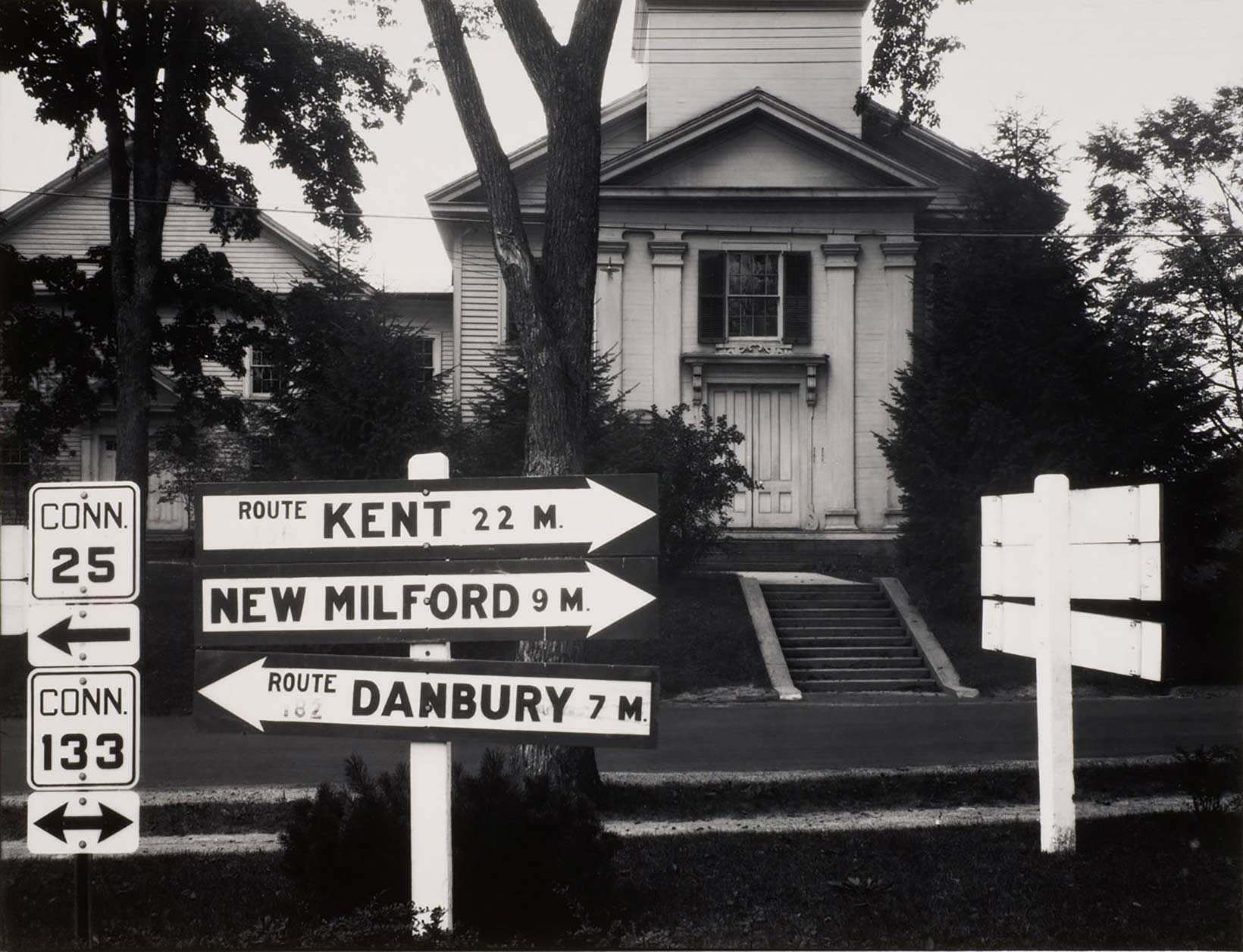

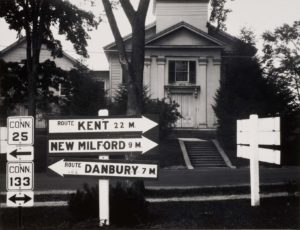

Brookfield Center, CT, 1930-31

As early as 1930, Walker Evans struck upon visual themes that would remain strong in his work over the next forty years. Evans captured this view of the Congregational Church of Brookfield, Connecticut, as a part of a series on Victorian architecture commissioned by Lincoln Kirstein, then an undergraduate at Harvard. “I was working by instinct but with a sense—not too clear—but a firm sense that I was on the right track, that I was doing something valuable and also pioneering aesthetically and artistically. I just knew it,” Evans recalled in a 1971 interview.

Though not as centrally framed as his later iconic images of churches across the American Southeast, this shot foreshadows their stark, silhouetted frontality. The inclusion of directional road signs, a frequent subject in his 1970s Polaroid work, reminds us of the scope of Evans’ lifelong appreciation of signs, which he began to collect (or “liberate” as he called it) decades later, displaying them in his home as works of art.

Walker Evans, Private Collection

New Orleans Houses, 1935

On assignment for the Farm Security Administration, Walker Evans frequently photographed vernacular housing, street scenes, and signs. His decision to photograph the facades of buildings, like New Orleans Houses, in such a direct manner focuses the viewers’ attention and piques our curiosity about the location. Evans places us in the street, staring at the houses as if we mean to enter them. The houses, however, are closed off to the viewer, with doors and windows shuttered, shades pulled, and curtains drawn.

Between the conspicuously depopulated public zone of the street and the walled off world inside the homes, the porches and balconies are a middle ground where the railings, columns, and fences block, rather than invite, our entrance. Evans kept his distance, as do we.

This image appeared in the 1938 exhibition American Photographs at the Museum of Modern Art, the museum’s first major treatment of an individual photographer. A landmark exhibition, the show and its accompanying catalogue established both Evans’ career and the viability of the documentary style of photography as fine art.

Walker Evans, Private Collection

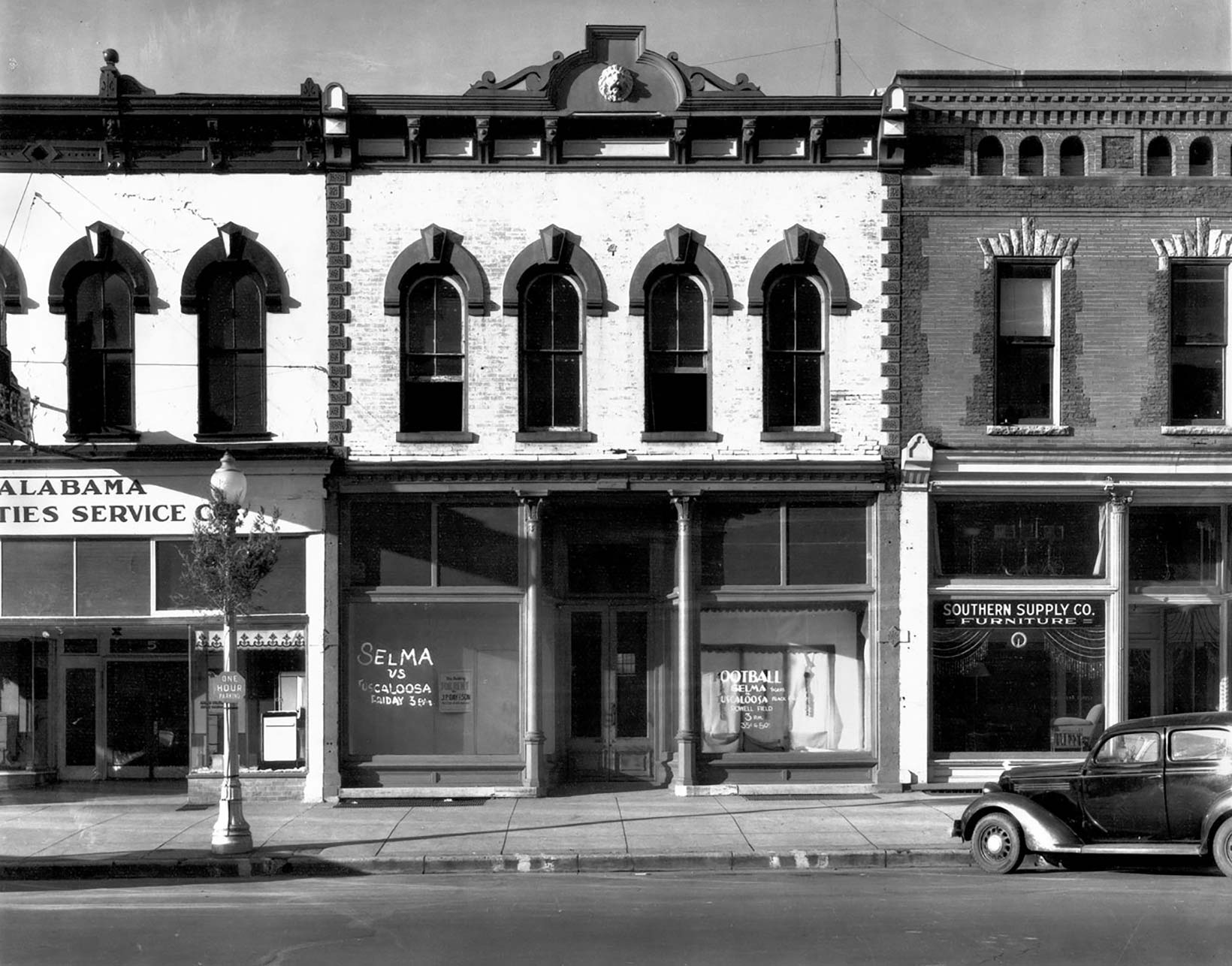

Main Street Block, Selma, Alabama, 1936

Walker Evans’ career as a fine art photographer traces back to his earliest exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art; not the celebrated American Photographs exhibition of 1938, but the very first show given to a photographer: 1933’s Walker Evans: Photographs of 19th Century Houses. Planned by MoMA’s director Alfred Barr and Evans’ friend Lincoln Kirstein, the exhibition was intended to complement a retrospective of the painter Edward Hopper running concurrently at the museum. Evans’ and Hopper’s shared aesthetics have long been recognized, and the visual similarity between this photograph of Selma, Alabama, and Edward .

Hopper’s painting Early Sunday Morning (1930, Whitney Museum of American Art) provide an excellent example of their affinities. Hopper’s Early Sunday Morning was included in the MoMA retrospective and certainly studied by Evans during the run of his exhibition. Later, however, Evans denied any influence: “This is a case of parallel. I didn’t know Hopper or what he was doing. I was doing very similar things. It just happens. It’s one of the wonders of the art world.”

Walker Evans, Private Collection

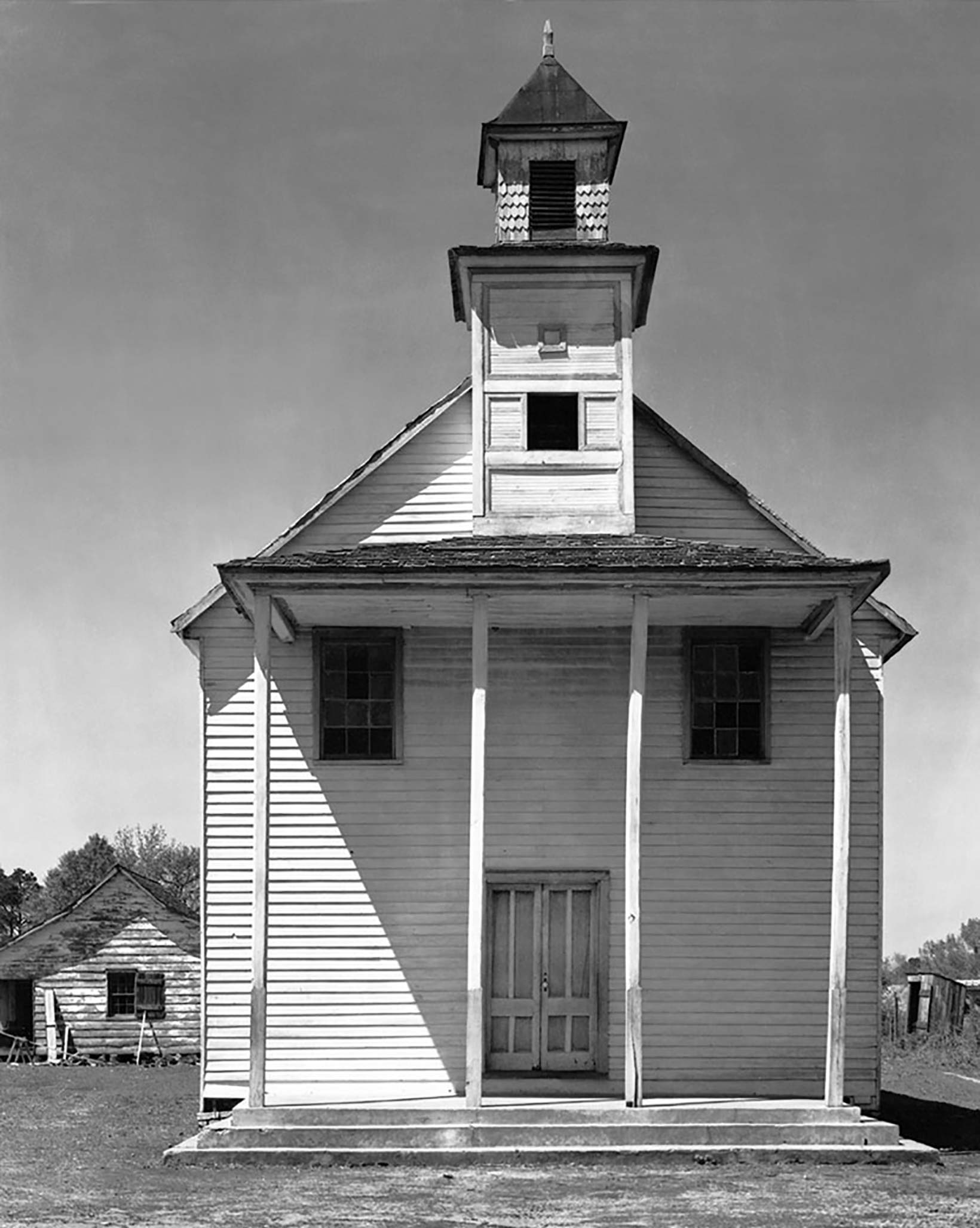

Negro Church, South Carolina, 1936

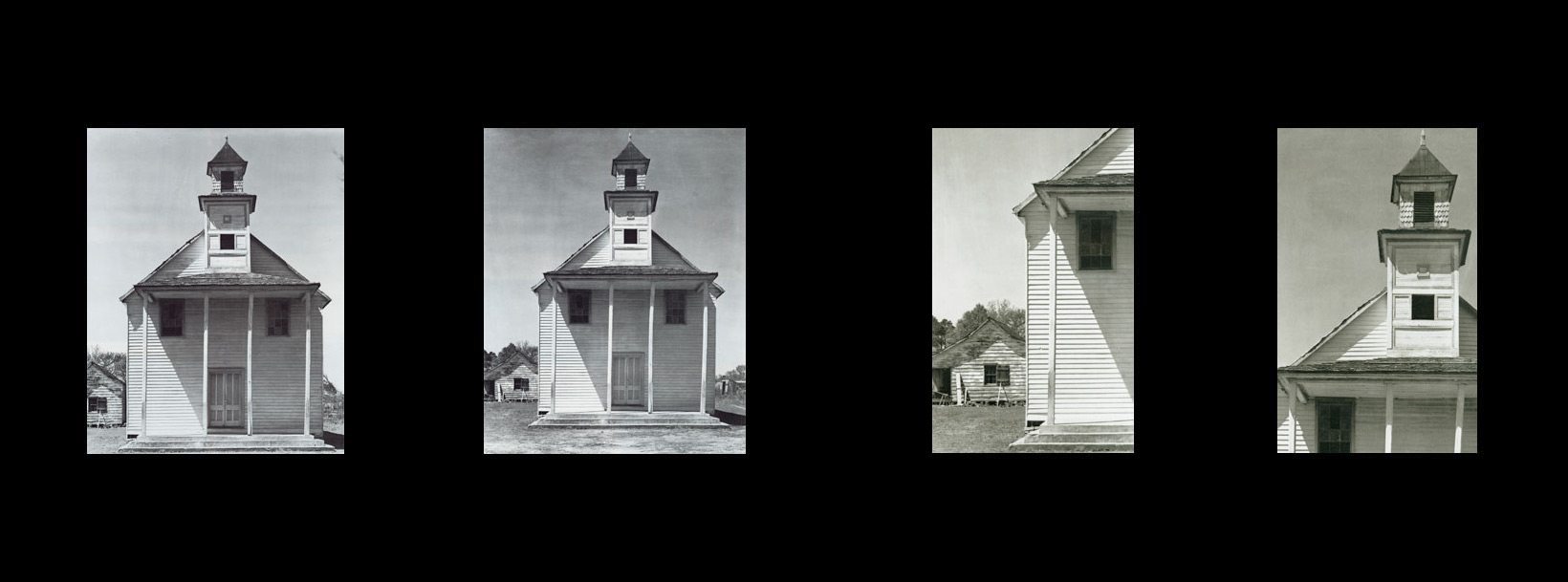

Walker Evans’ earlier concentration on photographing Victorian architecture trained him in capturing the façades of buildings. Although always sensitive to the quality and kind of light when working with a camera, architecture posed a particular challenge for him; “you have no control over where the sun is and where the building is placed,” he explained. Two different exposures of this church in South Carolina, with slightly adjusted focal lengths reveal a patient Evans waiting as the shadows crept across the whitewashed facade.

In contrast to the high style architecture he photographed in New England, and even the plantations he shot in the South, his series of Southern church photographs document their bare bones design. Evans’ frontal approach to the churches emphasizes the stark geometry of their pared down columns and cupolas. Shadows, when they appear, are as strong and linear as the architecture itself.

Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of the Walker Evans Estate ©Walker Evans Archive, Metropolitan Museum of Art

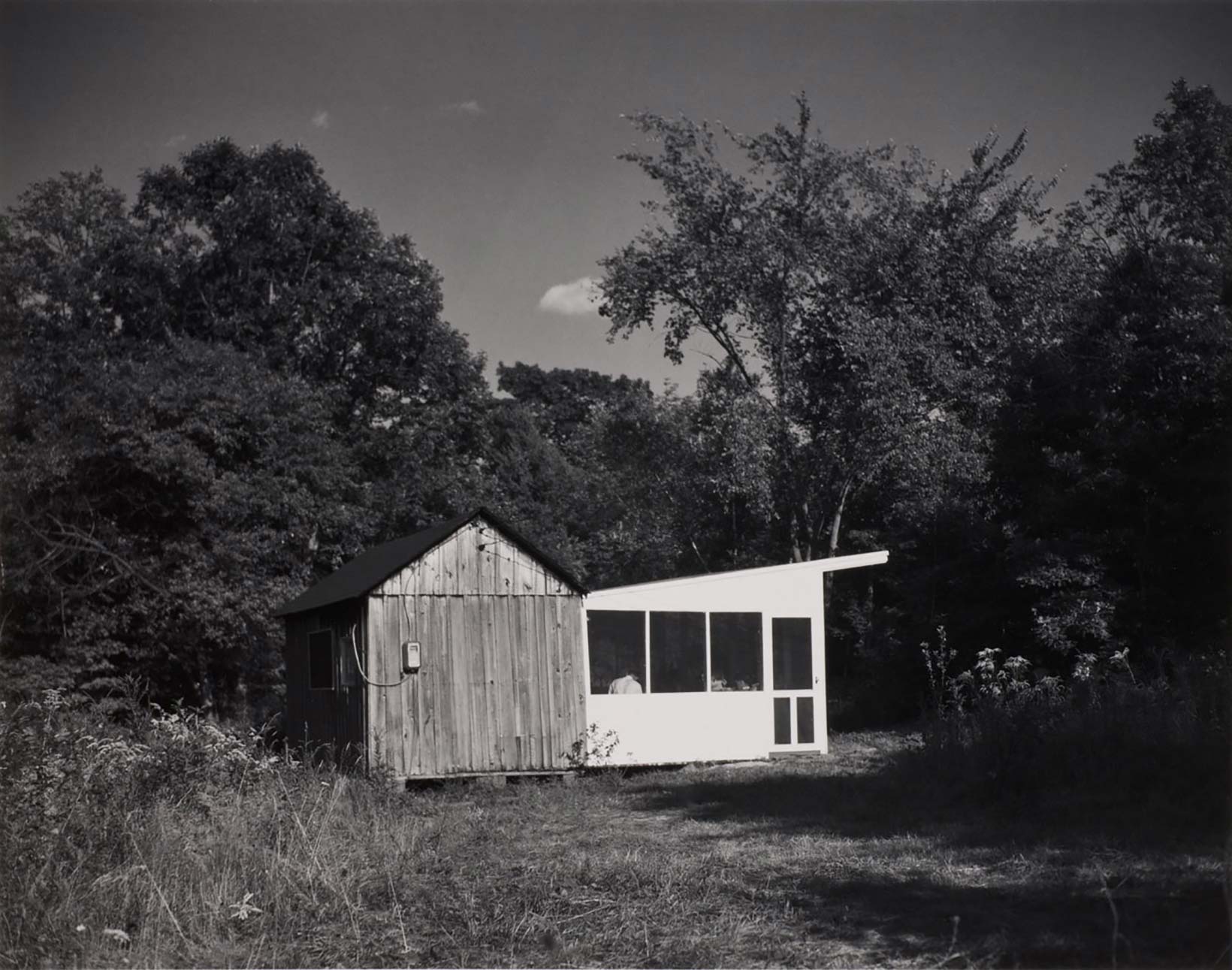

Early Dawn Farm, Route 156, Lyme, CT, ca. 1955

A careful and patient observer, Evans scoped out his surroundings, often considering how they would photograph. One particular barn near his home in Lyme attracted him for its Coca-Cola sign and the old timber he imagined using to build a studio one day. Stopping to show it off to visiting friends, Evans pointed out, “When we come back around six, half of this wall will be in the shade, divided diagonally by a sharp line. That’s not the right light for my pictures.”

Another barn in Lyme, however, was right for his images. On his way to and from his home, Evans traveled along Route 156, passing the Early Dawn Farm as he went.

To make this picture, he stood on the opposite side of the country highway with the light coming from the west, in the late afternoon of a winter’s day. The face of the barn is illuminated, but overrun with shadows from the trees, both the one in the frame and unseen others behind Evans. In addition to this photograph, Evans stopped to capture the building again with his Polaroid camera in the 1970s, waiting for precisely the same lighting to paint shadows of the now larger tree branches across the façade.

Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of the Walker Evans Estate ©Walker Evans Archive, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Walker Evans House, Lyme, CT, 1940s

Jane Smith Ninas, Walker Evans’ first wife, introduced him to Lyme, Connecticut, where she spent time visiting her old college roommate Billie Voorhees, daughter-in-law to the Lyme Art Colony painter Clark Voorhees. After Evans and Ninas married in 1941, they frequently visited Lyme, where Jane gardened and used the building seen here as a painting studio. In the 1940s, they added on a whitewashed modern screened porch to the original chicken coop, more or less taking over a portion of the Voorhees property as their own.

This photograph is part of a sequence of more than two dozen images taken as Evans circled the building, examining it from all angles with his camera. Not until the mid-1960s, once he began teaching at Yale, would Evans build a proper home in Lyme. Designed by Yale architecture student Robert Busser, the contemporary style of the new house on Grassy Hill Road remains, even today, an unusually modernist statement in the countryside of Lyme.

Walker Evans, Private Collection

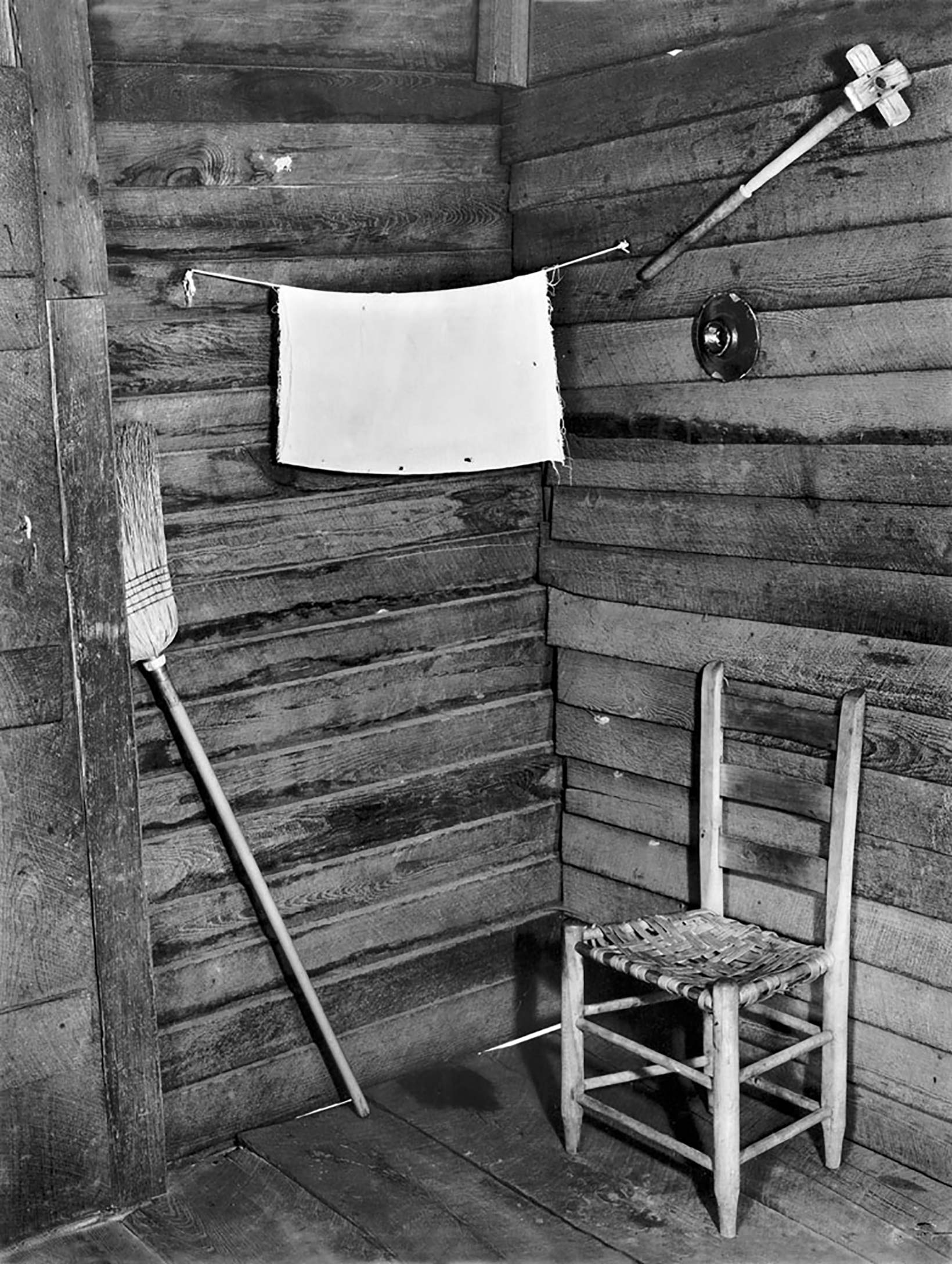

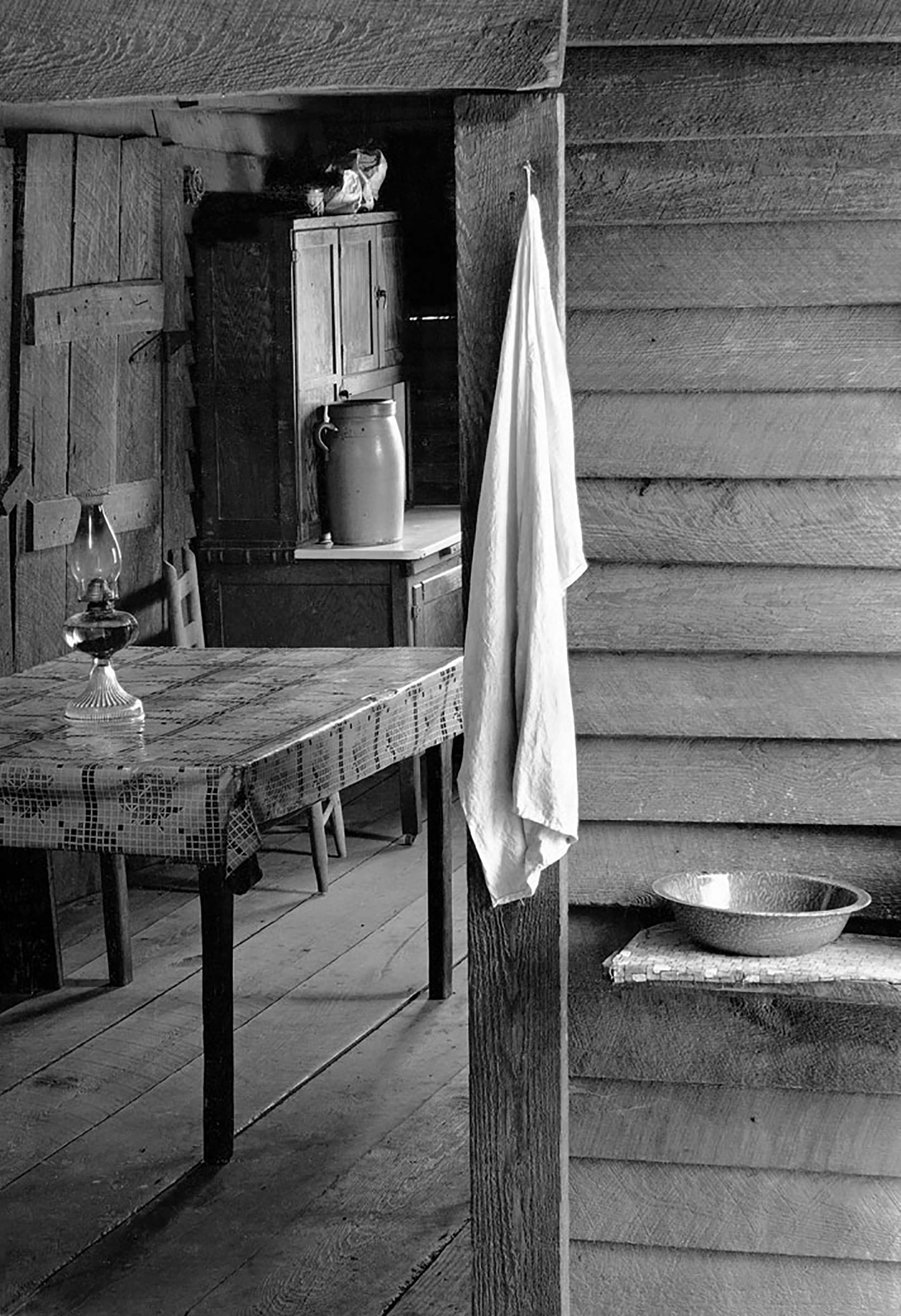

Kitchen Corner, Tenant Farmhouse, Hale County, Alabama, 1936

While working in the South photographing sharecroppers and tenant farmers, Evans aimed to find the potential beauty in their surroundings. Even though he was sent by a government agency as an “information specialist” he resisted the idea of using his images as propaganda. He felt “that his fellow Americans would respond more sympathetically to a positive portrayal of tenant life than to a morbid curiosity with dirt, disease, or suffering” explains historian James Curtis.

Every element of Kitchen Corner was carefully composed by Evans to evoke the mood he was hoping to convey. Evans went as far as to move the kitchen table and bench out of the room in order to fit his tripod in the precise location he desired. “I do feel that I like to suggest people sometimes by their absence. I like to make you feel that an interior is almost inhabited by somebody,” he explained. Evans’ arrangement and editing of the world around him extended to his own life and home, which was a carefully curated space.

Walker Evans, Private Collection

Farmer's Kitchen, Hale County, Alabama, 1936

The kitchen of the Burroughs family, one of the subjects of Walker Evan’s and James Agee’s book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, deeply interested Evans as a compositional and technical problem. Two windows in the kitchen provided ample lighting, allowing Evans to forego the use of a flash with his large format camera. In his first attempts to photograph the room, however, the brilliant light proved difficult to control. Evans solved the problem by shifting sideways and eliminating the window from his camera’s view.

The resulting image appears to be an effortless snap of the shutter highlighting the depth of the space illuminated from an unseen source.

Evans’ colleague Agee remembered the kitchen scene in a different way. He described the small room as an extremely hot place in the summer, overcrowded with a table, chairs, and stove. Agee also focused on the sheer dirt and clutter of the space, neither of which are evident in Evans’ photograph.

Walker Evans, Private Collection

Gourd Birdhouses, Hale County, Alabama, 1936

Walker Evans’ image of a gourd tree holds a particular place of honor in the revised edition of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, which he co-authored with James Agee. In the book, a portfolio of Evans’ photographs from Hale County, Alabama, precedes all of the text, standing as its own essay on the three sharecropper families profiled in the pages that followed.

In the preface to the text, Agee attempts to make the role of the photographs clear, understanding that this type of word and image combination was uncommon. “The photographs are not illustrative. They, and the text, are coequal, mutually independent, and fully collaborative.

By their fewness, and by the impotence of the reader’s eye, this will be misunderstood by most of that minority which does not wholly ignore it. In the interests, however, of the history and future of photography, that risk seems irrelevant, and this flat statement necessary.”

After Agee’s death, Evans assisted in preparing the second edition of the book, the most notable alteration of which was the doubling of the number of photographs. The 1960 edition’s photos conclude with this image of gourd birdhouses.

Walker Evans, Private Collection

Sharecropper's Daughter, Hale County, Alabama, 1936

Walker Evans photographed Dora Mae Tengle, seen here, and her family as a part of his collaboration with James Agee. This image of Dora Mae was not among those selected for the book, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, which was eventually published in 1941. In the sequence of photographs of the young woman, now a part of the Library of Congress collection, Evans began shooting at a distance. At first Dora Mae was dwarfed by the barn that surrounded her, boxed in by the doorway in which she stood.

As Evans moved closer to his subject, Dora Mae loomed larger in the vertical frame, even as Evans’s shadow encroached upon her. The grimace on Dora Mae’s face as she looks out into the bright sunlight at times looks like a self-conscious grin suppressed while the photographer and his camera examined her. In the closest shot—the one that appeared in the book—Evans moved slightly to the side of her, to avoid darkening her face with his own shadow. Her stance remains unchanged, but Dora Mae’s eyes followed Evans, regarding him with a mix of skepticism and curiosity as he went about his work.

Walker Evans, Private Collection

Tenant Farmer's Daughter, 1936

As a means of obscuring the identities of the sharecropper families they documented, Walker Evans and his collaborator James Agee used pseudonyms in the text of their book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Despite the way Evans’ photographs laid bare so much of the farmers’ lives, withholding their names made their stories more universal and preserved a semblance of privacy.

Evans wrote that although an artist was not “directly able to alleviate the human condition. He’s very interested in revealing it.” The tragedy of this belief is poignantly revealed in the story of ten-year-old Lucille Burroughs, called Maggie Gudger in the book.

Evans’ 35 mm lens followed her into the cotton fields with her burlap sack in tow and captured the intense gaze of her gray eyes in this 1936 portrait. Five years after posing for Evans, when the book was finally published, Lucille was married, pregnant, and still picking cotton. In the mid-1950s, when Evans had moved on to a career with Fortune magazine, Lucille was a thirty-year-old grandmother in rural Alabama. In 1971, the year of Evans’ major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art where the Burroughs family was once again on display, Lucille committed suicide.

Walker Evans, Private Collection

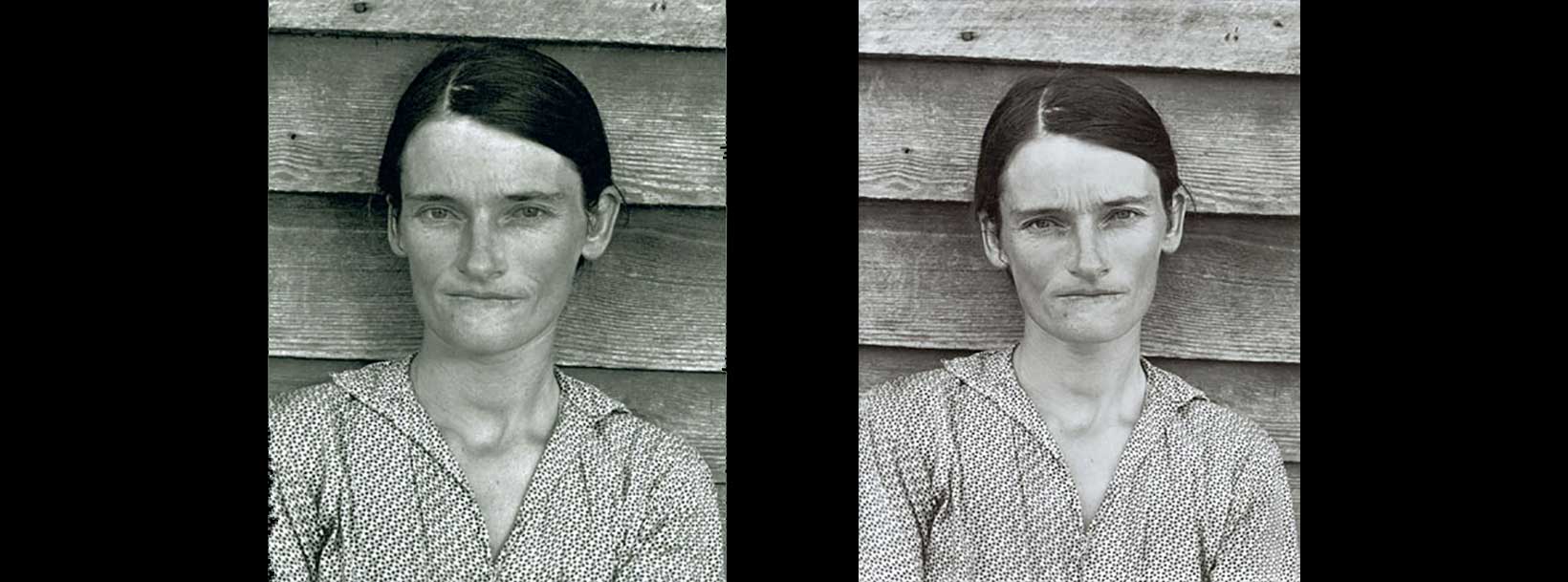

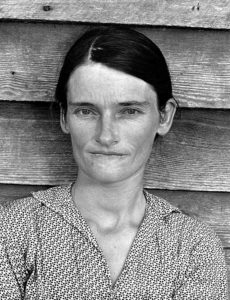

Alabama Cotton Tenant Farmer's Wife, 1936

Although portraiture in the traditional sense rarely interested him, Walker Evans’ photograph of Allie Mae Burrough’s face, seen here, is among the most universally recognizable images in the visual discourse of poverty in America. In the sequence of photographs he made of the woman with her back to the bare wood siding of her home, her expression changes slightly in each exposure. Her brow furrows, she chews her lip, and the angle of her head shifts in a perceptible but natural way. She appears intensely aware of the photographer’s presence but innocently did not understand the consequences of the pictures being made and the social reform they would help to achieve.

To avoid the self-conscious modeling of portraits, Evans engaged in a number of experiments in anonymous portraiture in the years that followed. With his adoption of the Polaroid camera in the 1970s, Evans embarked once again on the kind of up-close examination of an individual seen in Allie Mae’s portrait. His late twentieth century subjects, however, were all too aware of the camera’s gaze and the implications of being captured by the noted photographer Walker Evans.

Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of the Walker Evans Estate ©Walker Evans Archive, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Old Black Point Beach, Niantic, CT, 1967

The beach at Old Black Point was a favorite spot of Walker Evans during the years he lived in Connecticut. Other photographs from this series show a gathering on the beach, a fife and drum corps on parade, and a clambake, all quintessential New England summer activities. Even in the cooler weather Evans enjoyed Old Black Point Beach as a spot for gathering driftwood, one of the many collections on display in his Lyme home.

In the sequence of photographs including this image, Evans shoots from behind the row of seated children, visually playing with the perspective of the straight lines formed by the corps.

In earlier parade images, such as the Fourth of July celebration in Bridgeport, Connecticut in 1941, Evans concentrated on the marchers. Other times he turned his lens to study the crowd of spectators. In this shot, Evans positions himself in a way that emphasizes the diagonal of the gaze shared by the small standing boy and the drum corps officer as they meet face to face.

Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Rudolph Besier in Honor of the Centennial. ©Walker Evans Archive, Metropolitan Museum of Art

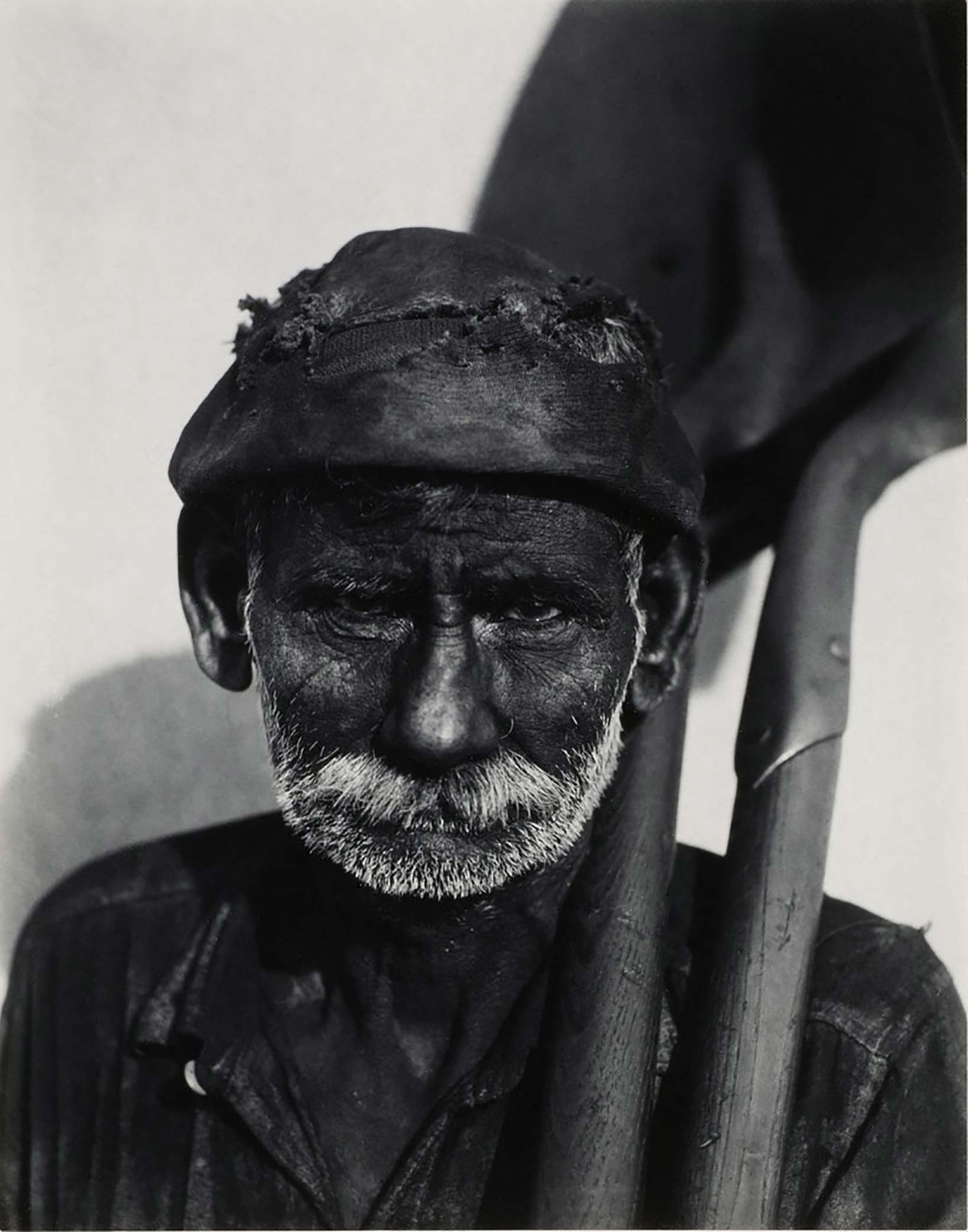

Coal Dock Worker, Havana, 1933 (printed 1971)

In 1971, Walker Evans partnered with the fine art publishing firm of Ives-Sillman to produce a fourteen-print portfolio showcasing his work from the 1930s. He selected this print as a representative of the work he did in Cuba, where he went to shoot accompanying photos for Carleton Beals’ book The Crime of Cuba. Even early on, Evans’ sense of independence as a photographer was clear. “I said I wanted to be left alone. I wanted nothing to do with the book. I’m not illustrating a book. I’d just like to just go down there and make some pictures but don’t tell me what to do. So I never read the book,” Evans recounted in a 1971 interview about the experience.

He would later make essentially the same demands of his other employers. With Evans’ supervision, Ives-Sillman produced an edition of eighty-eight portfolios of gelatin silver prints. In both this and another portfolio, produced by the Double Elephant Press in 1974, Evans looked back over his career taking the opportunity to select and re-edit familiar images. In 1971, retrospectives at the Museum of Modern Art and the Yale University Art Gallery did much the same work with a broader brush—MoMA’s exhibition showcased an astonishing 200 photographs.

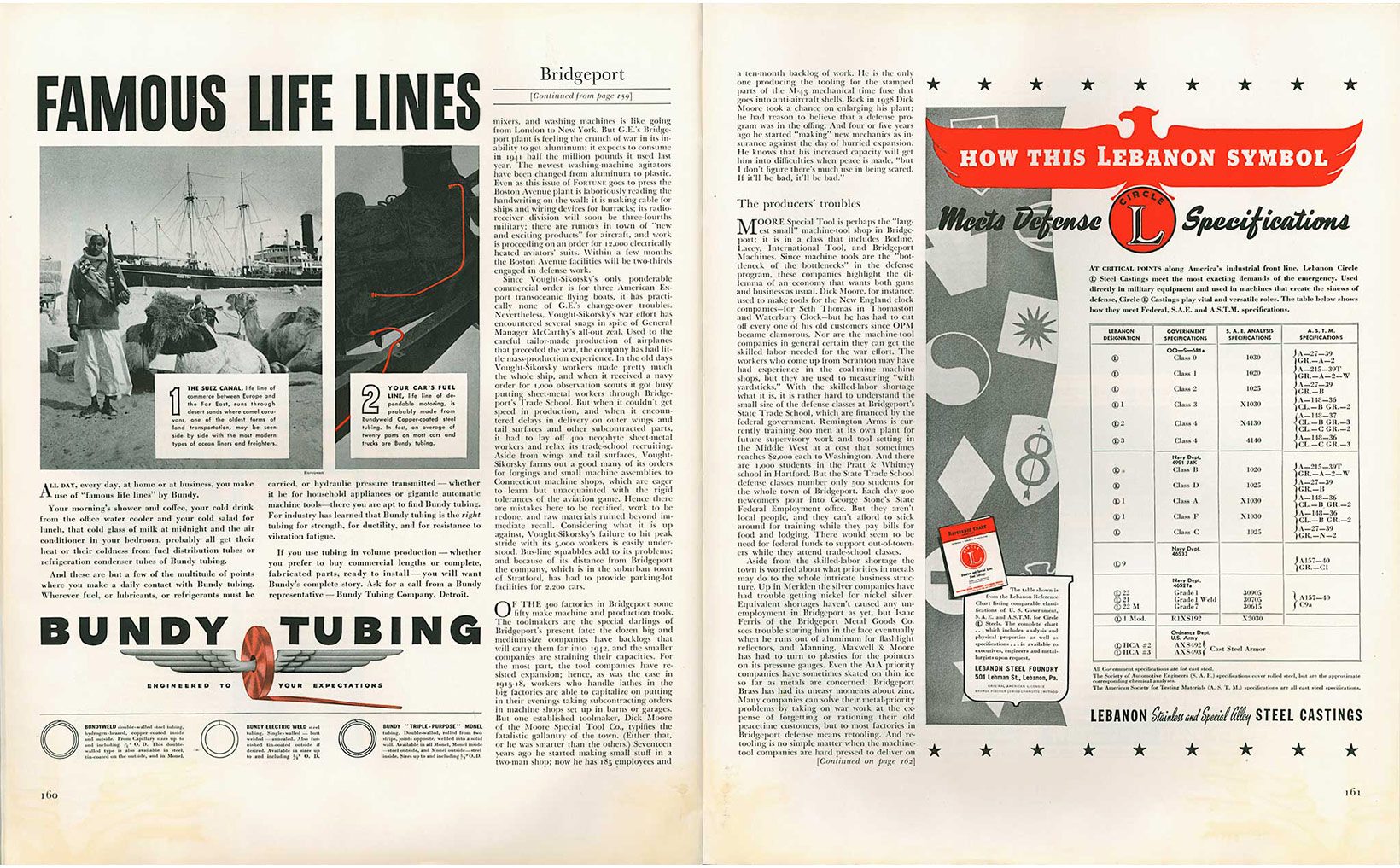

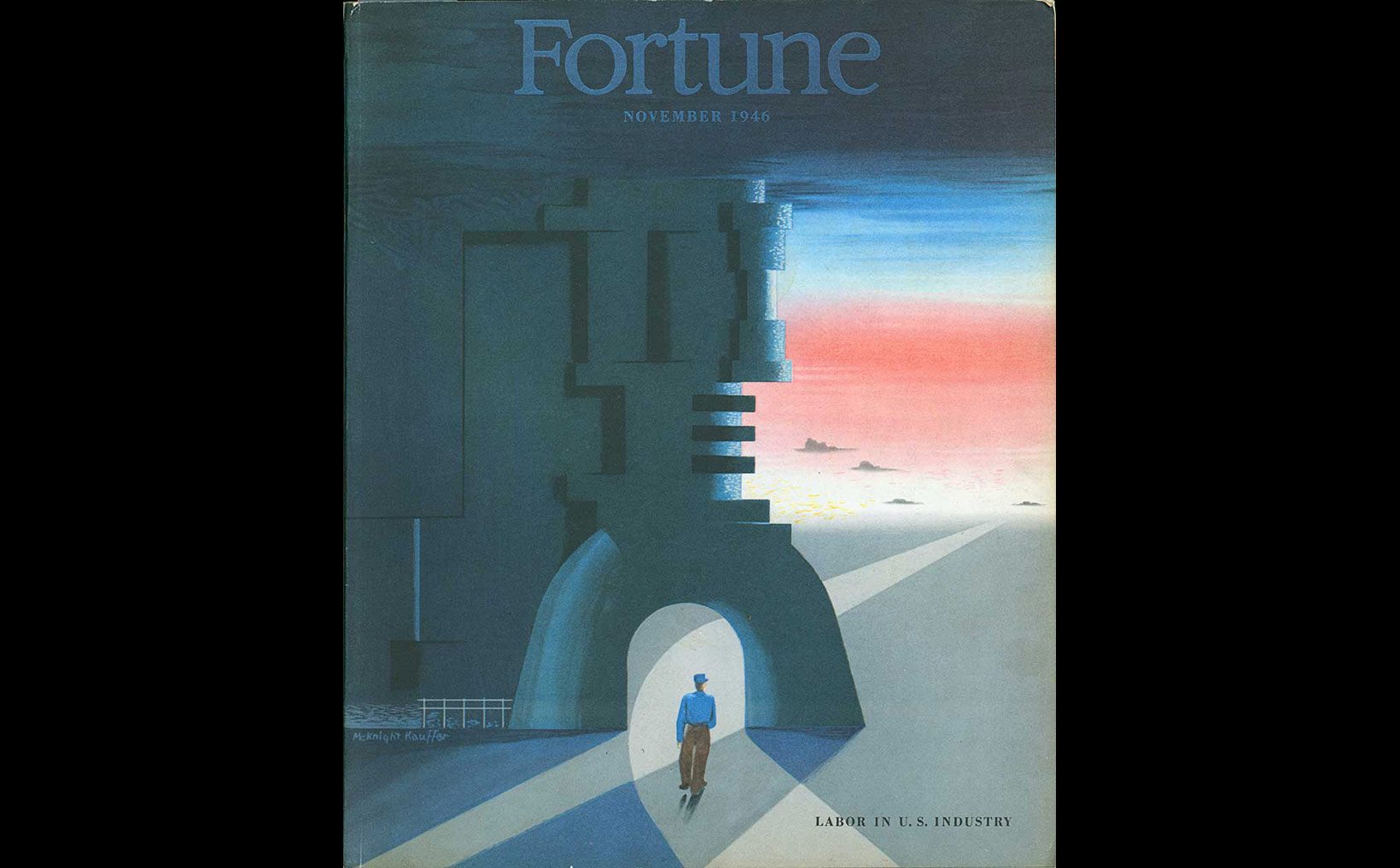

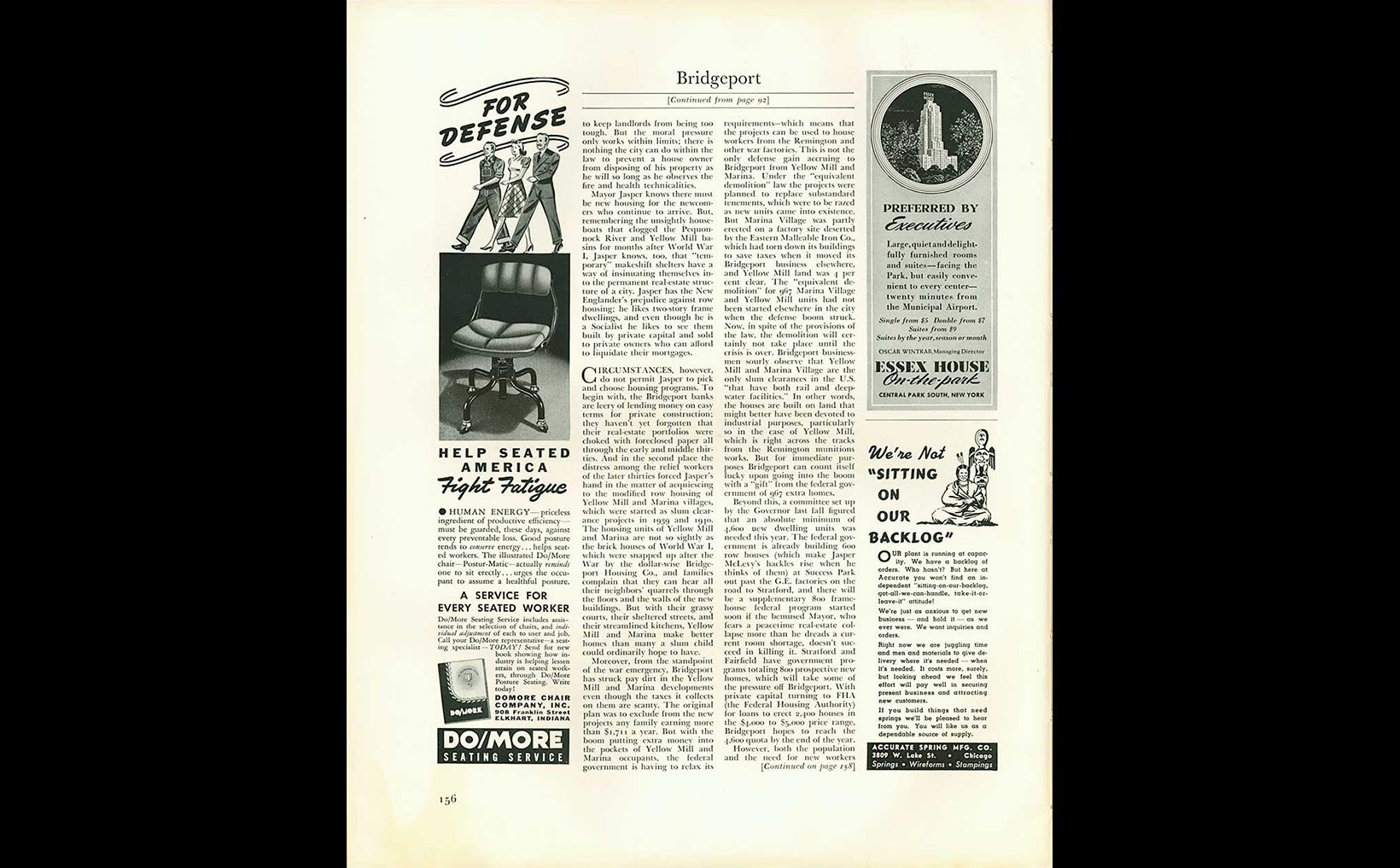

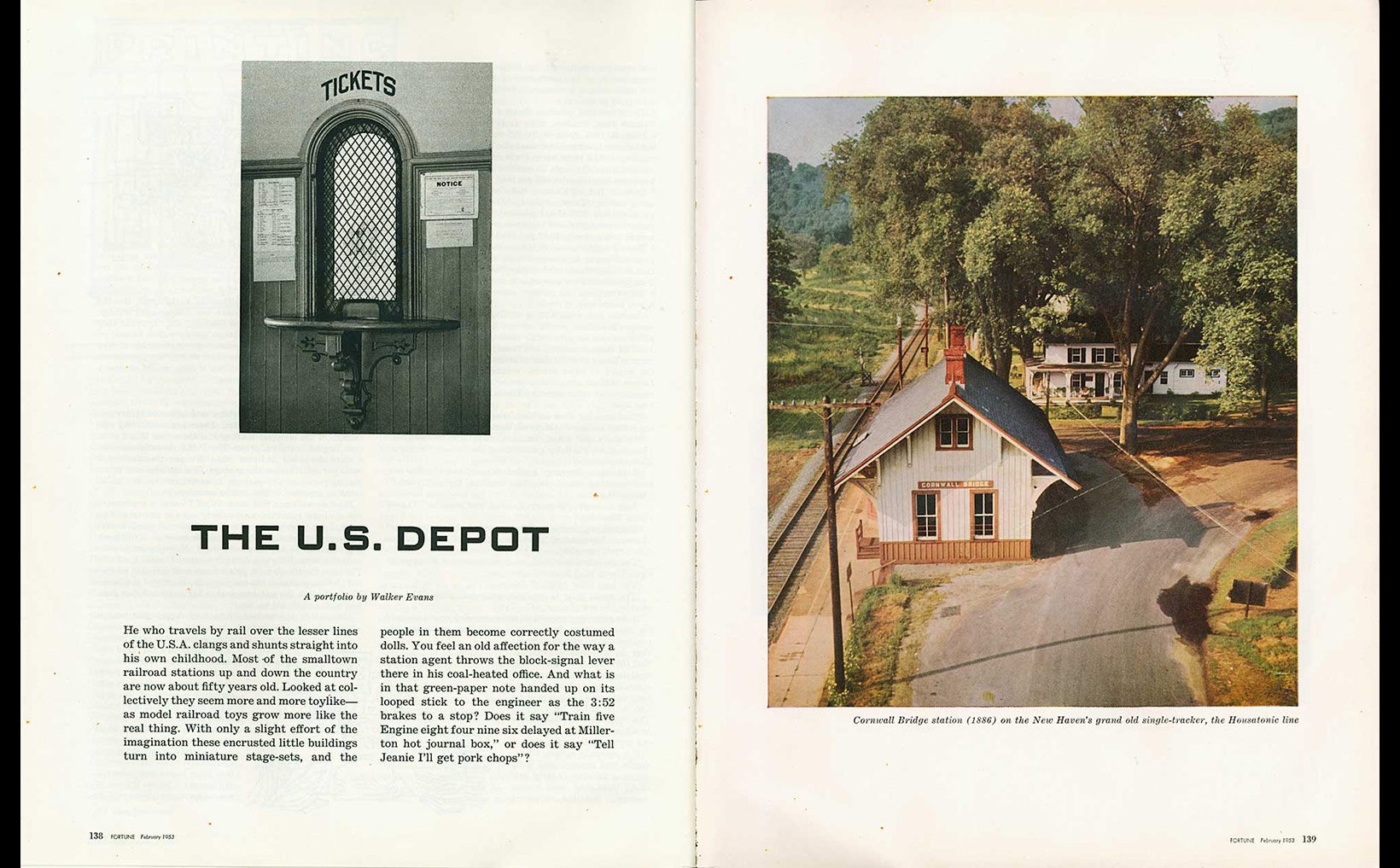

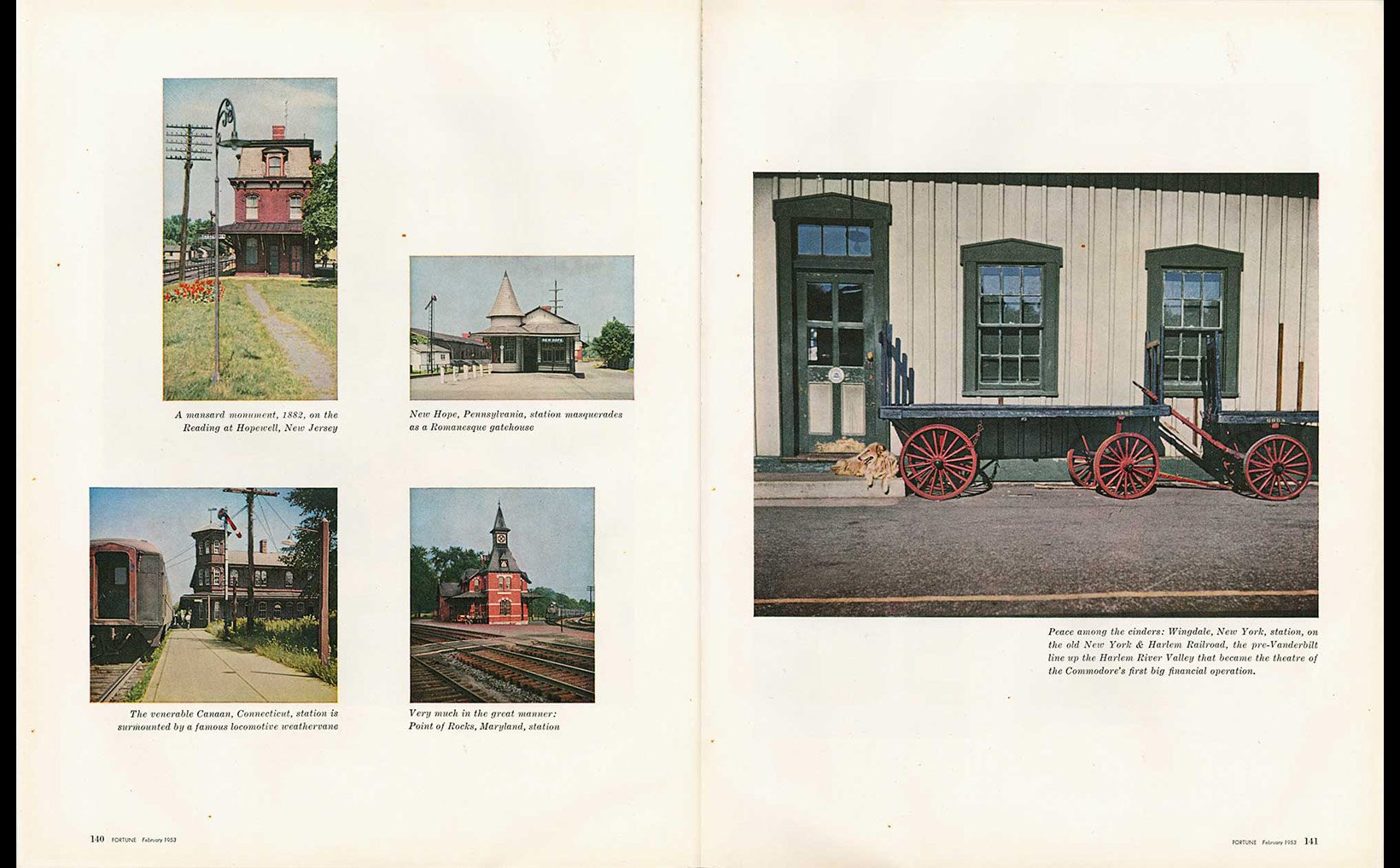

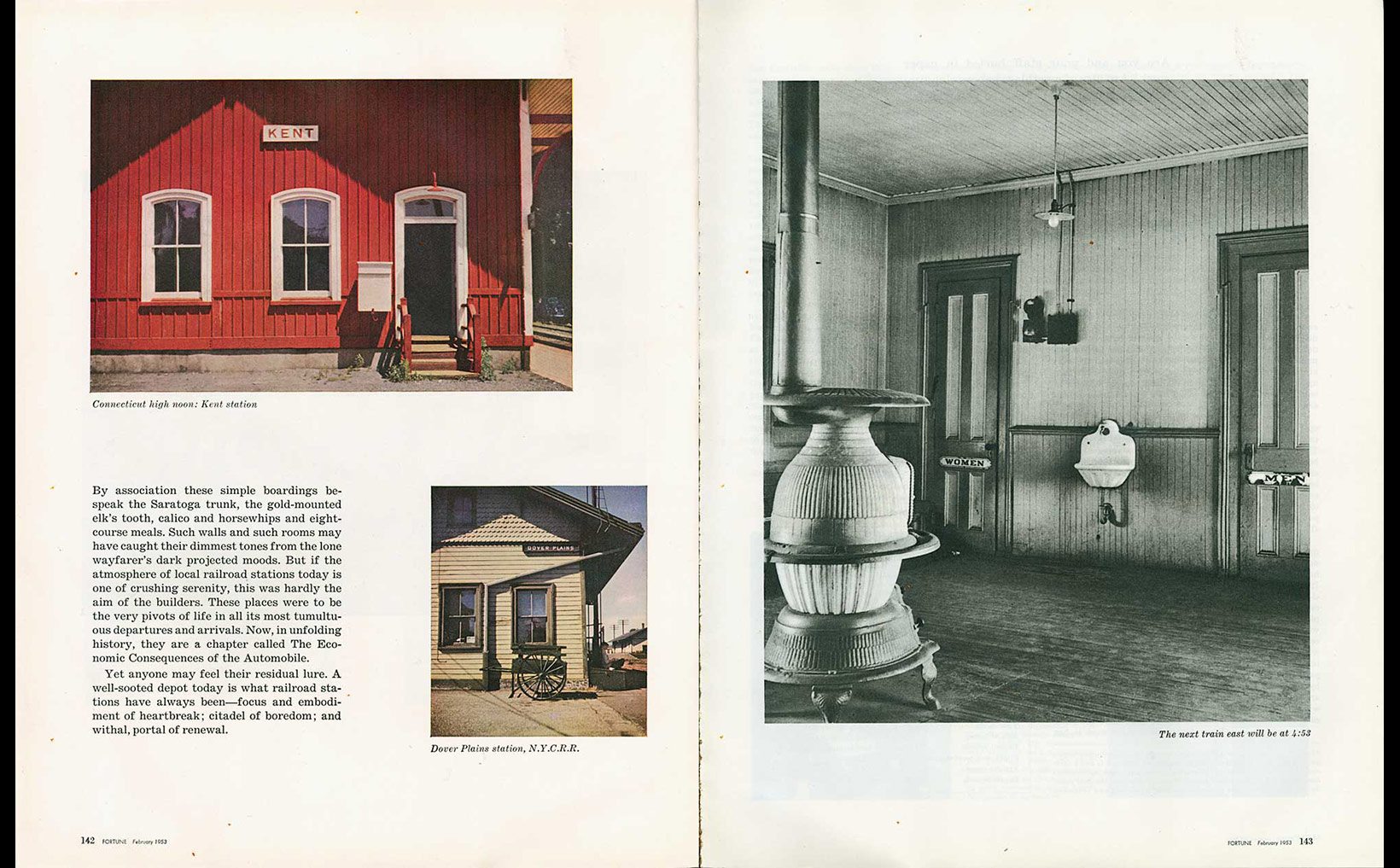

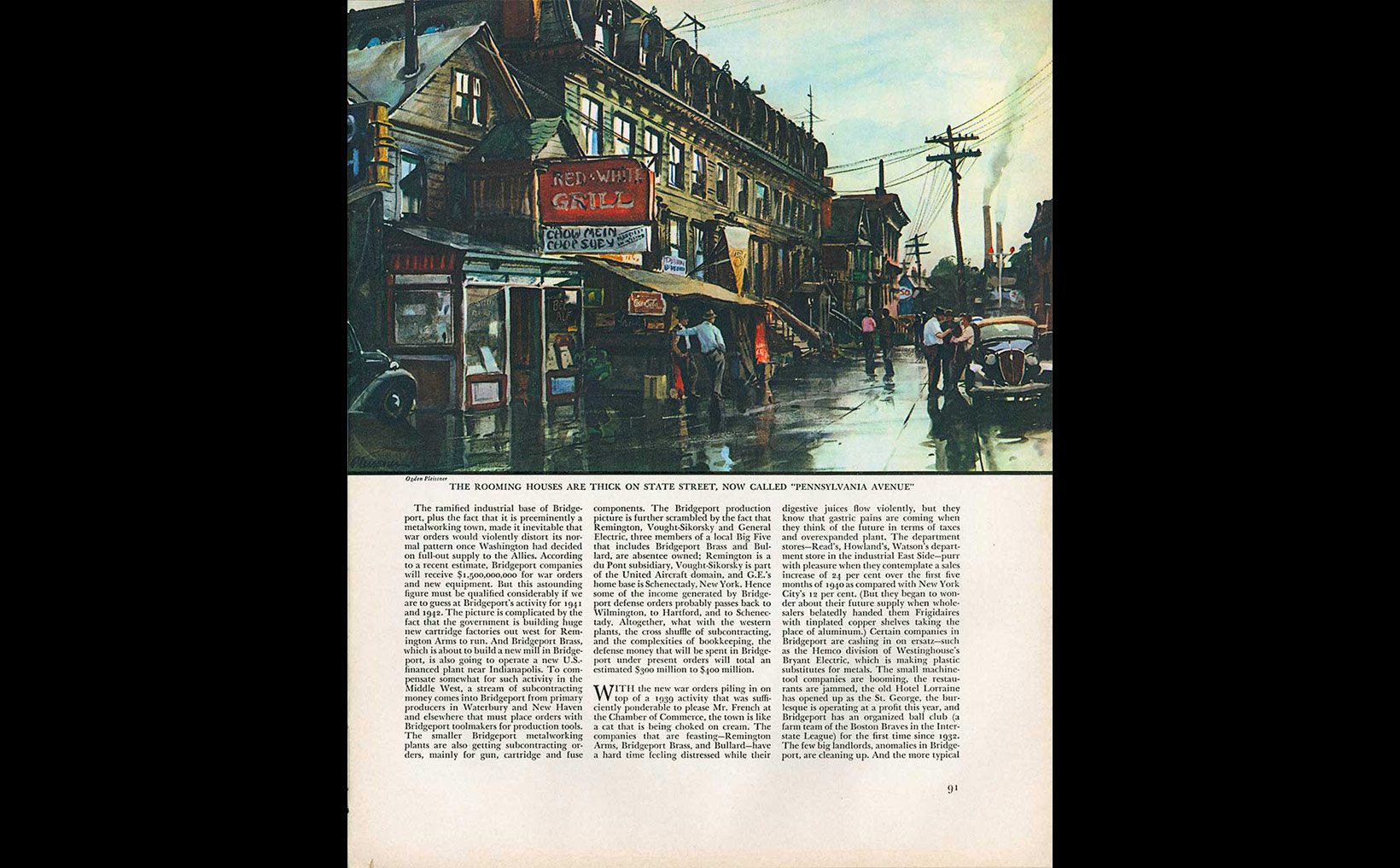

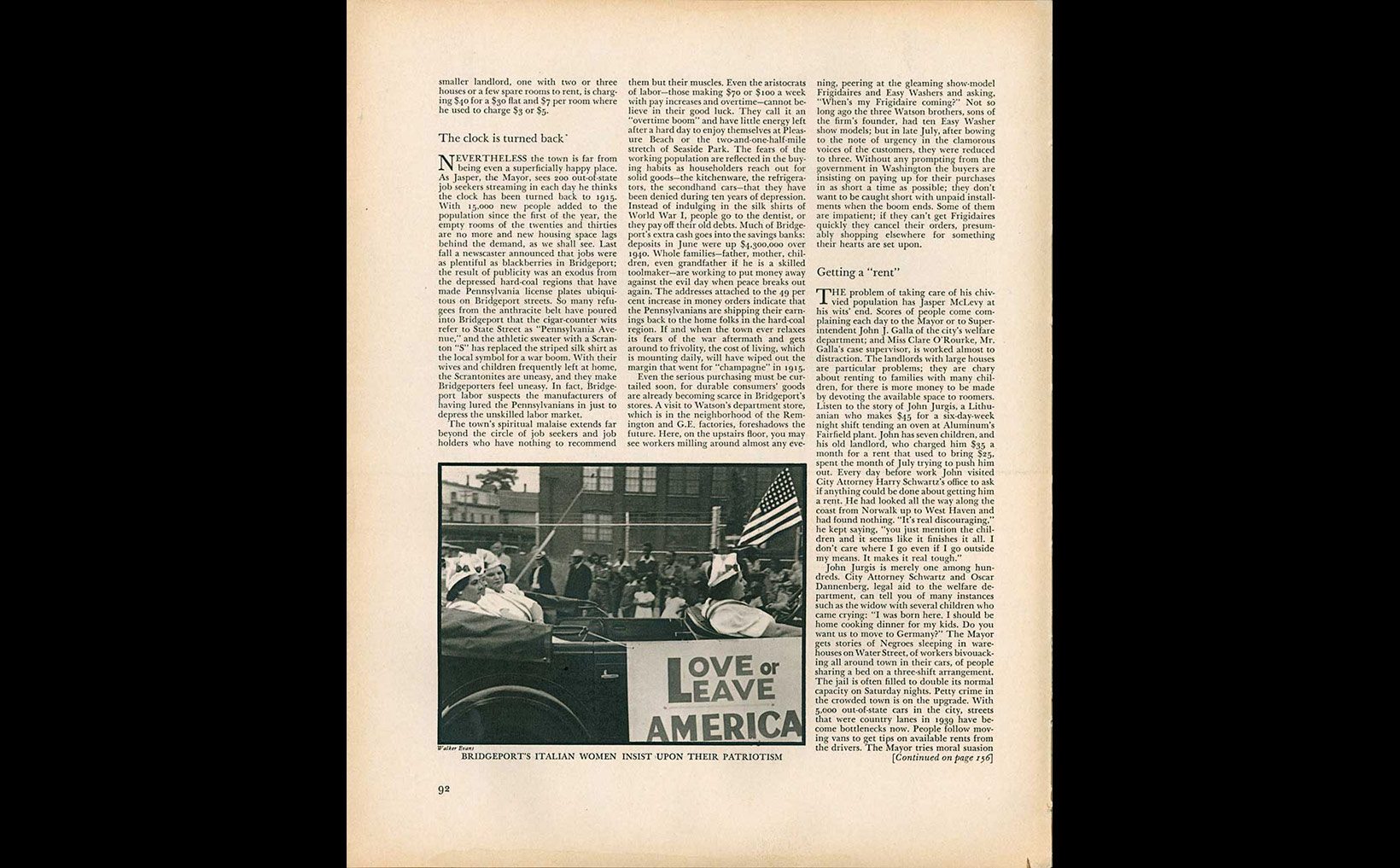

Fortune Magazine

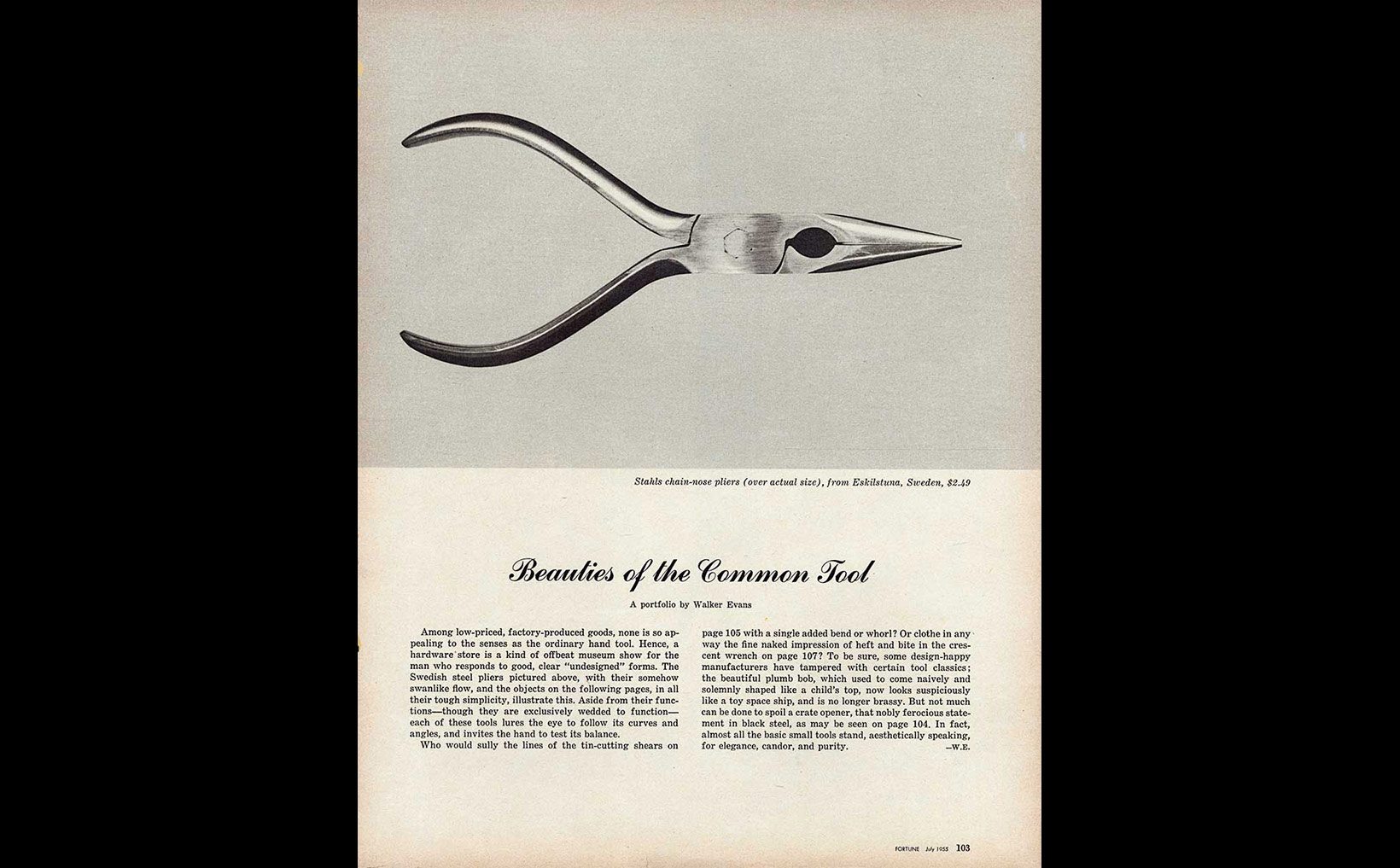

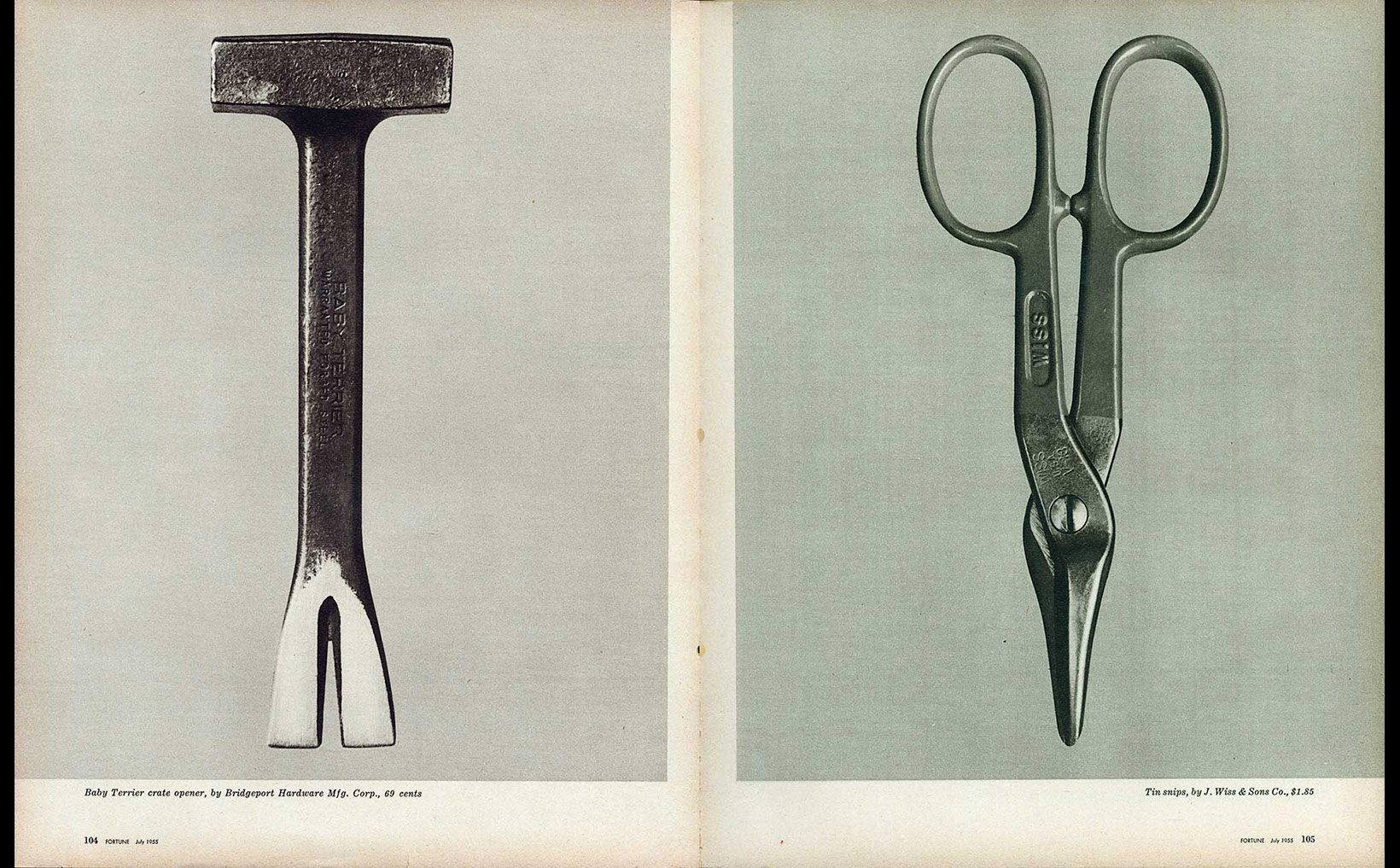

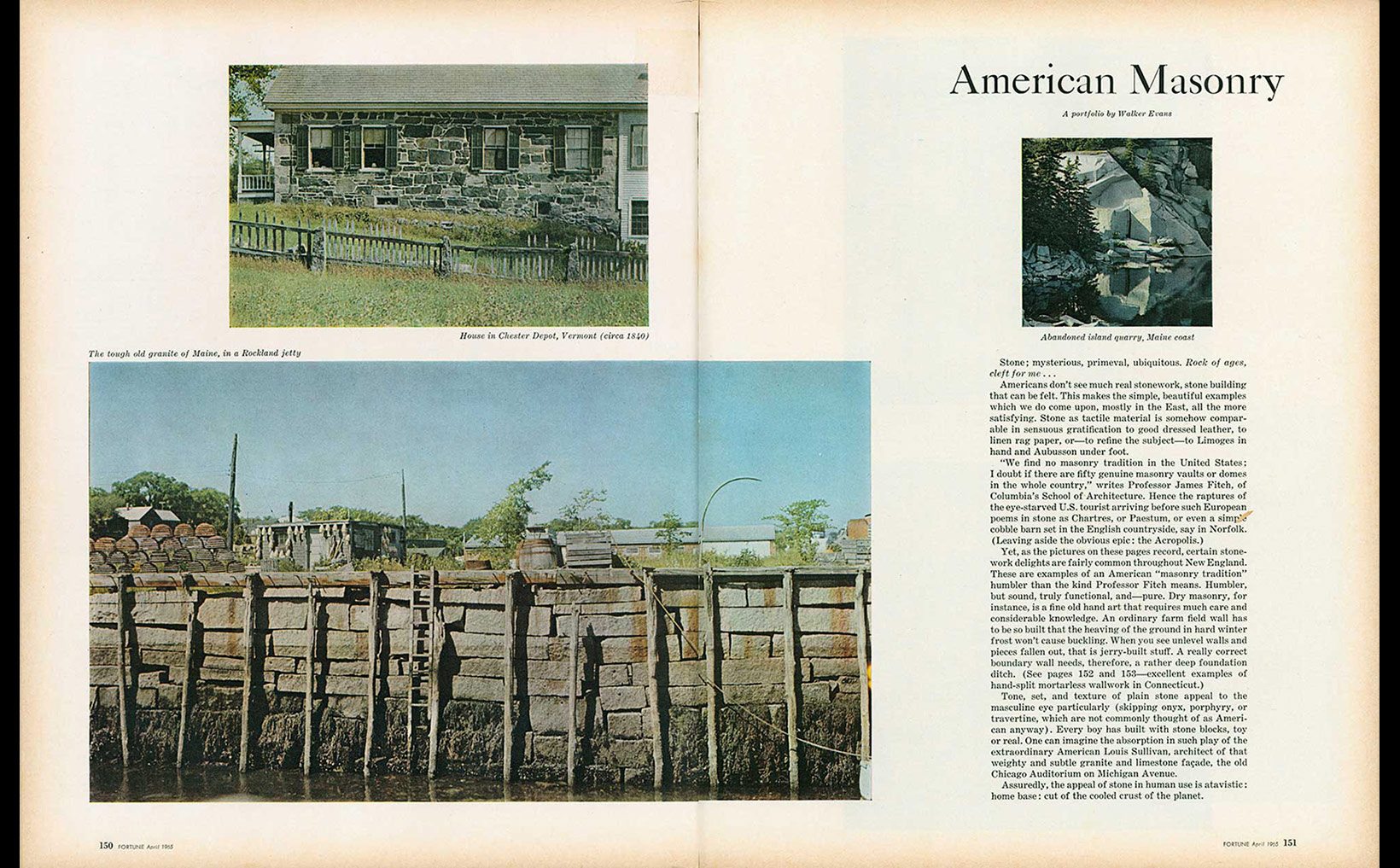

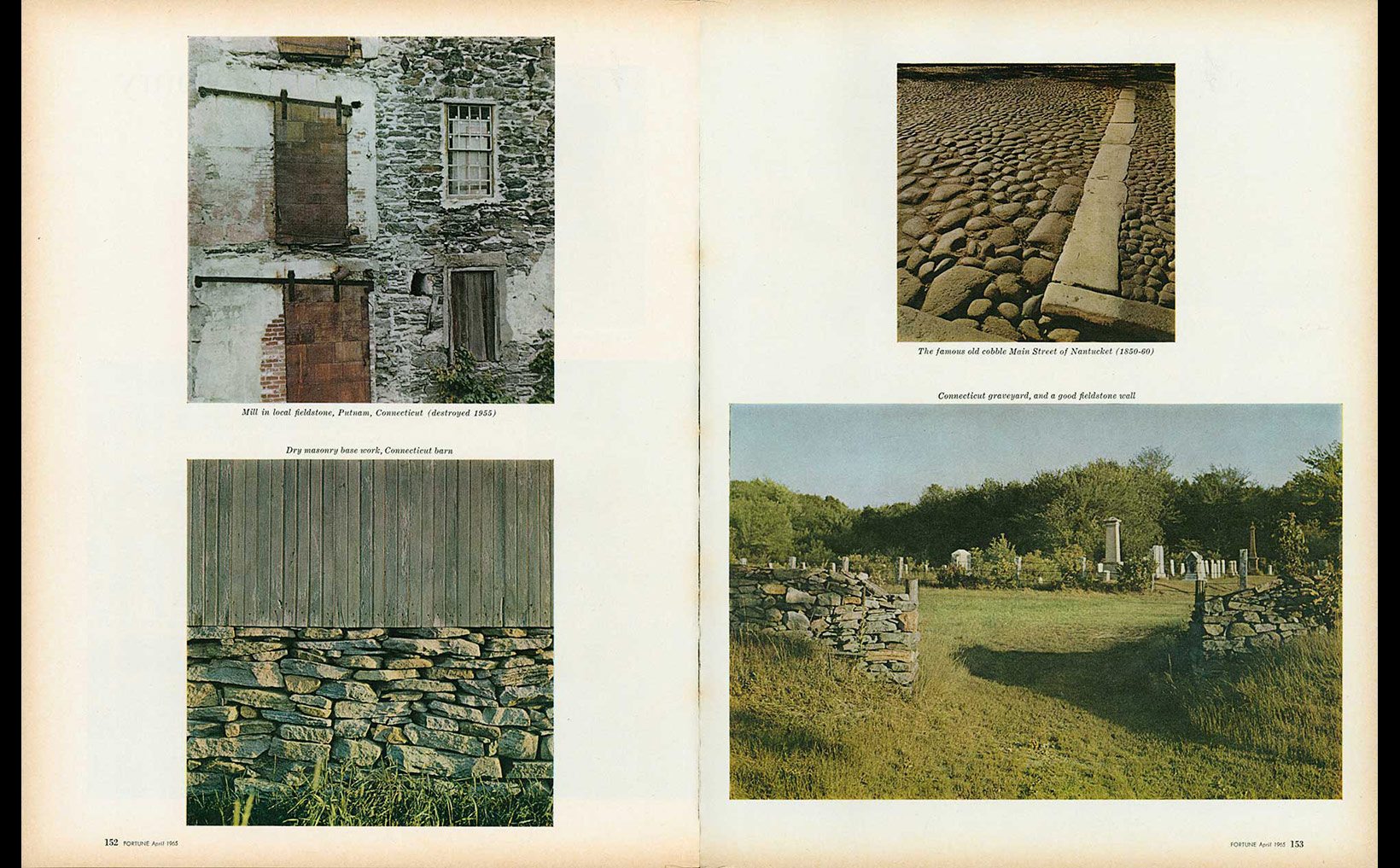

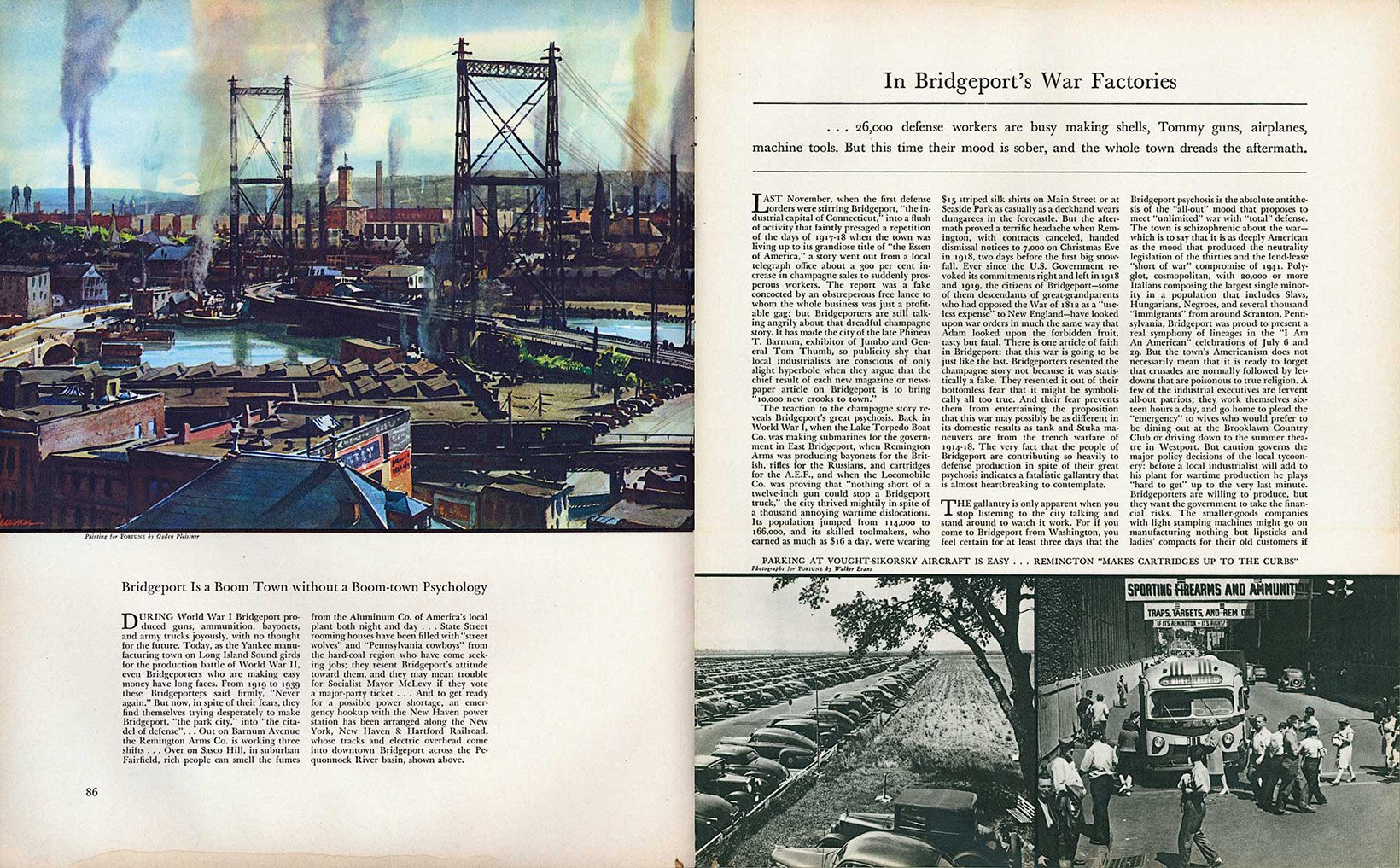

Beginning very early in his career, Walker Evans worked for Fortune magazine, on special assignments from 1934 to 1941 and as a photo editor from 1945 through 1965.

He published 372 photographs over that period, only a small fraction of the total number he shot for the magazine. In addition to taking the photographs, he devised his own assignments, frequently penned the accompanying essays, and worked up the page layouts. Founded only months after the start of the Great Depression, Fortune covered the international business world for the Time-Life media group. The magazine instantly gained a reputation as a high quality publication, with fine art on the cover and artistic features, like those by Evans, inside.

Compare

Cautious of the darkroom tricks utilized by others, Walker Evans said: “I don’t believe in manipulation… of any photographs or negatives. To me it should be strictly straight photography and look like it.”

Characteristic of his working style, Evans took many photographs of his selected subjects, approaching from different angles or using different cameras. Evans’ exacting eye worked tirelessly to capture the image in the moment, rather than in the darkroom after the fact. In the course of his experimentation, the variations between the shots can sometimes appear subtle. Although we cannot reconstruct all of the complex decisions made by Evans’, both artistic and technical, it is possible to read the variant images in relation to one another, in an effort to see what he saw.

Comparison A

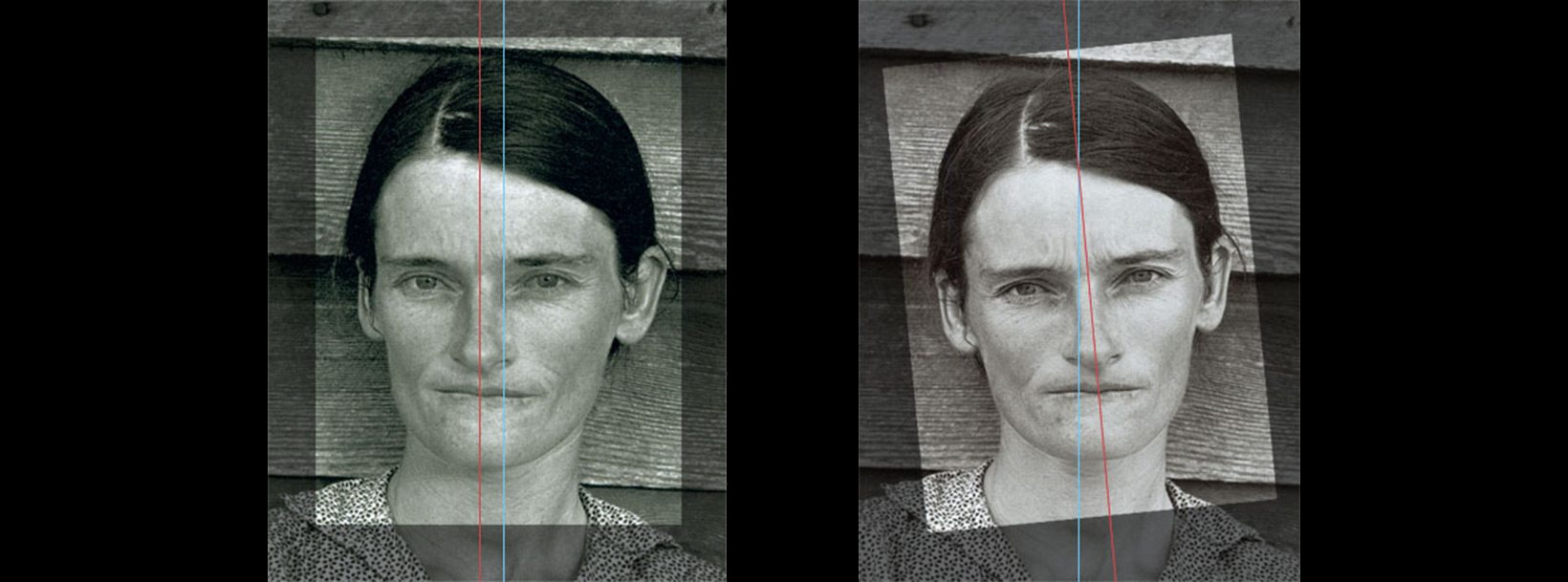

MODEL: In a series of photographs taken of Allie Mae Burroughs, the camera, lens, film, and nearly everything but the model are the same from image to image. The slight variations in Allie Mae’s facial expressions differentiate the photos. In the first image, her expression, while stoic, is somewhat gentle, compared to the second where the tip of her head to one side and the furrow of her brow combine to seem as if she is scrutinizing the viewer. The second image is the one selected for the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

Comparison B:

SETTING: Although the setting does not shift in these images, it is important to notice how Walker Evans’ selection of the location influences the interpretation of the images. Allie Mae’s portrait is taken with her back against the exterior wall of her home. The powerful lines of the heavily-grained bare wood boards are repeated in the strong horizontals of her mouth and eyebrows, particularly in the first image, where her brow line continues the line of the board behind her.

Comparison A

LENS CHOICE: When comparing images 1 and 2, the dominant difference is in the choice of lenses. In the first photograph, Evans uses a longer lens, which appears to compress space. The steps of the church are at the edge of the frame and the building to the left appears closer than it does in the second version taken with a wide-angle lens. Switching lenses also changes our perspective of the scene so that the tree branches (upper right) and the distant outhouse seem to disappear.

Comparison B

CROPPING: Evans collected postcards and experimented in printing some of his images in postcard format. In images 3 and 4 he has selected details from his 8×10 inch negative made with a wide-angle lens and turned them into postcards. In contrast to the full frame negative, in which the church is central and symmetrical, the cropped versions literally push the church to the side. The presentation in image 3 conceals any sign of the building’s function, while the cupola in image 4 could be an embellishment on a country barn rather than a house of worship.

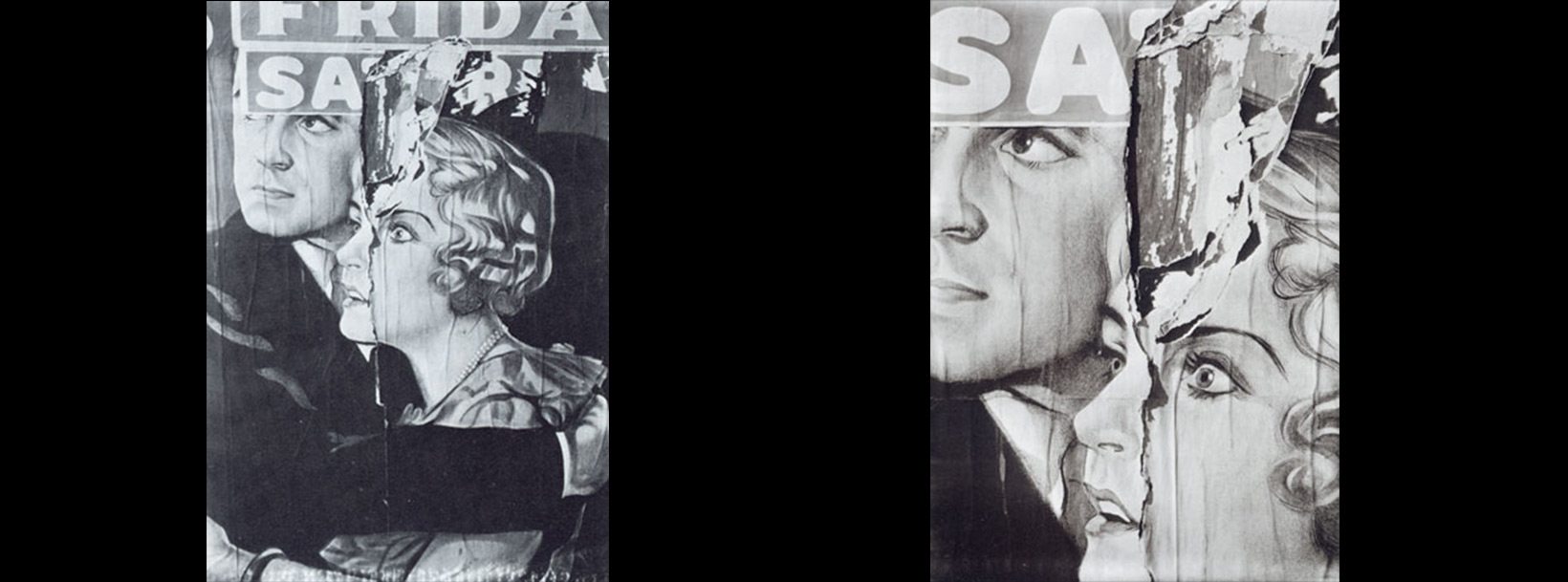

Comparison A

FRAMING: In this photograph of a portion of a movie poster it is easy to imagine that Evans simply reprinted a cropped version of his negative to produce image 2 of this comparison. They are, in fact, two separate negatives. In the first, more of the poster is visible and we observe the man’s protective embrace. In the second version, the narrative is truncated and the tear in the poster dominates the image, appearing as a gash in the woman’s face. In the varied framing of his subject, Evans heightens the drama in an already dramatic image.

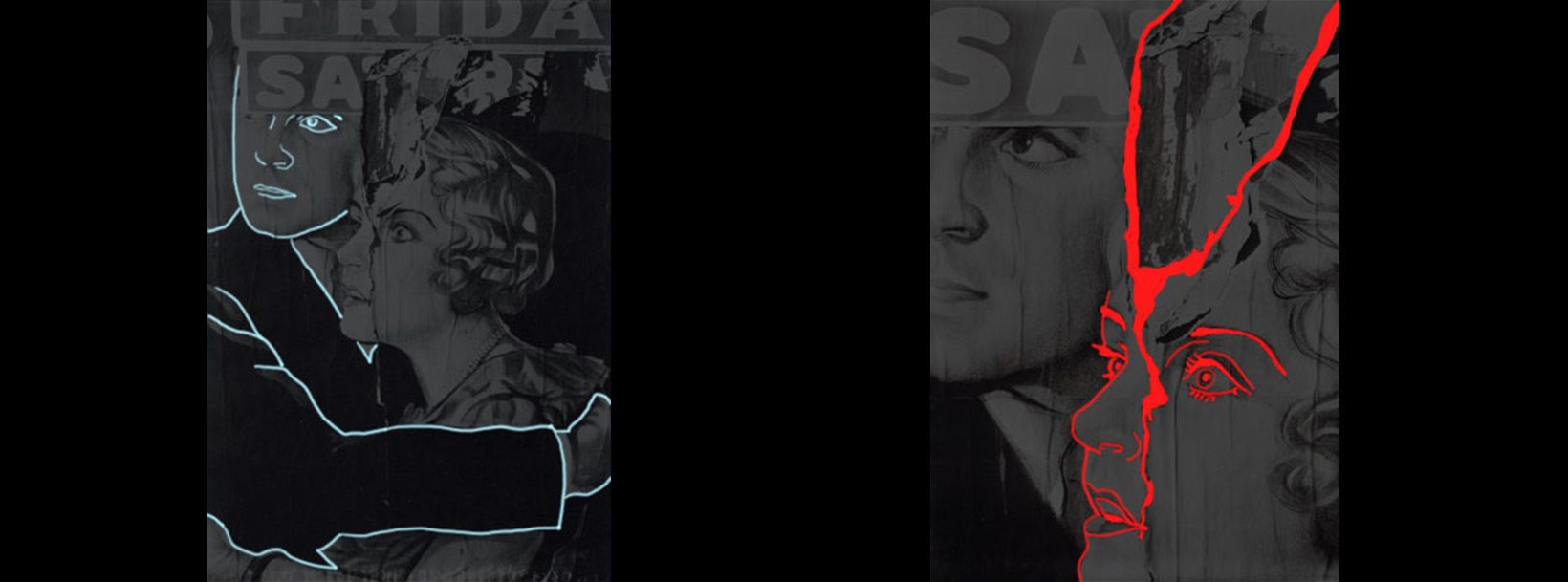

Comparison A

FORMAT: The rapid change from vertical to horizontal format is seen in these snapshots of Dora Mae Tengle. Using a 35mm camera without a tripod permitted Evans the freedom of spontaneous movement not allowed by the larger view camera. In this sequence he approaches Dora Mae, capturing her full height and the strong vertical of the barn in the first image. In the second image, as he gets closer and steps to the side, turning the camera, the barn’s interior structure is exposed and rather than posing, Dora Mae appears to be passing by the camera.

Comparison B

SHADOWS: Shadows frequently play a role in Evans’s photographic compositions, even in their absence. The strong frontal light he often preferred in photographing building façades is used here in Dora Mae’s portrait. While she casts virtually no shadow in either photograph, Evan’s own presence is felt in the shadow he casts in the vertical image. The bold diagonal shadow in the horizontal image echoes the girl’s stooped posture, as if the barn and its shadow are pressing down upon her.

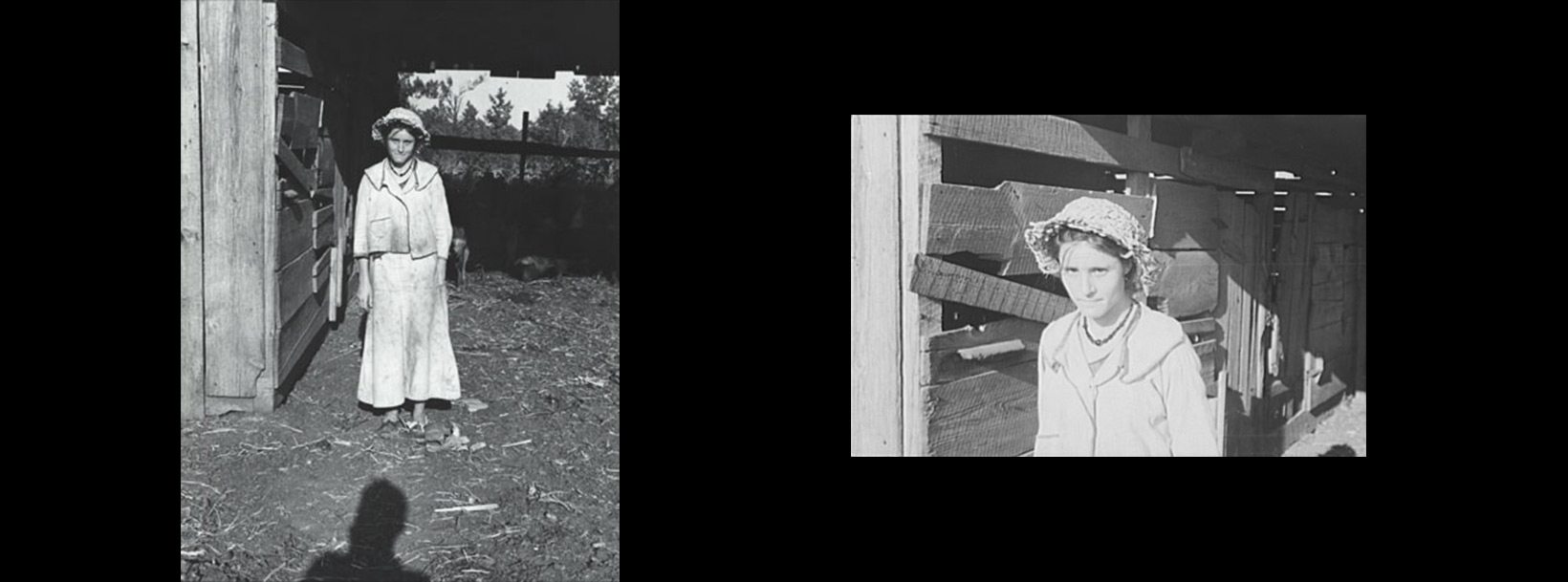

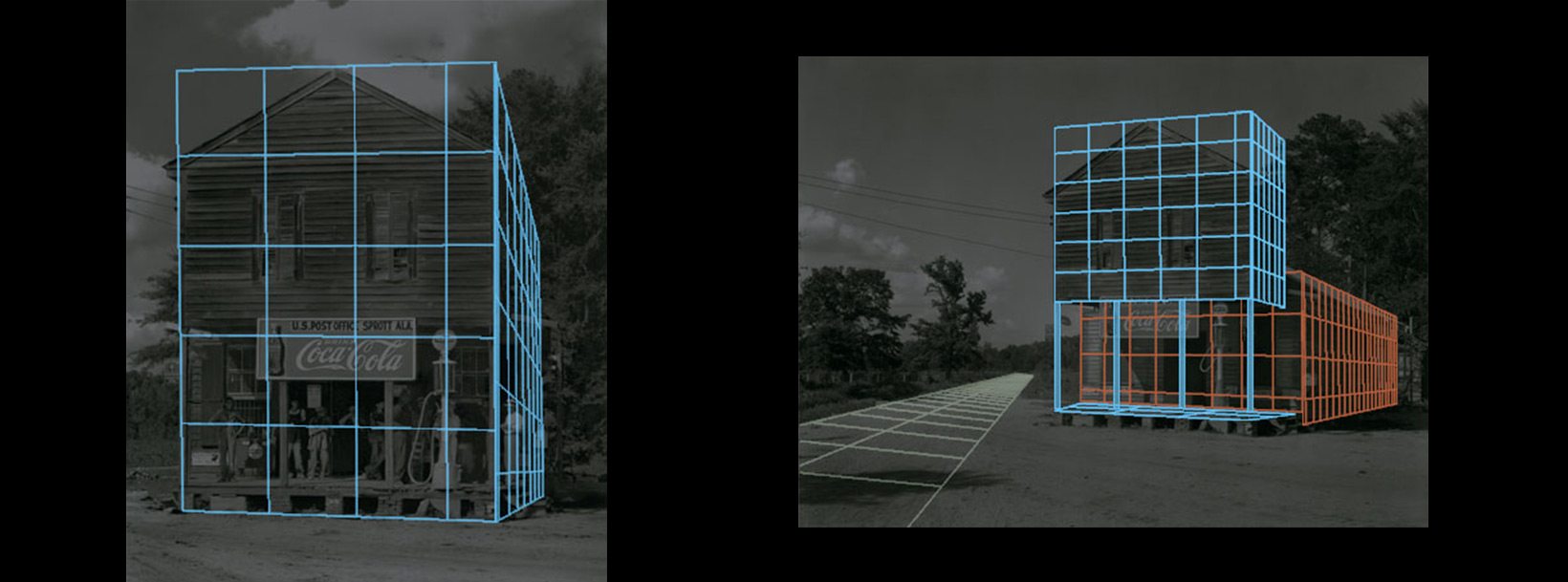

Comparison A

CAMERA POSITION: By changing the position of his camera Evans can reveal the true structure of the building his is photographing. Image 1, photographed straight on, appears to be a large two-story structure, possibly in a row of similar stores in a small village. The vantage point of image 2 shows the actual structure of the building, a shallow façade teetering on spindly posts, fronting a low-slung shed. From this perspective the building appears isolated, a lonely landmark along the dusty country lane.

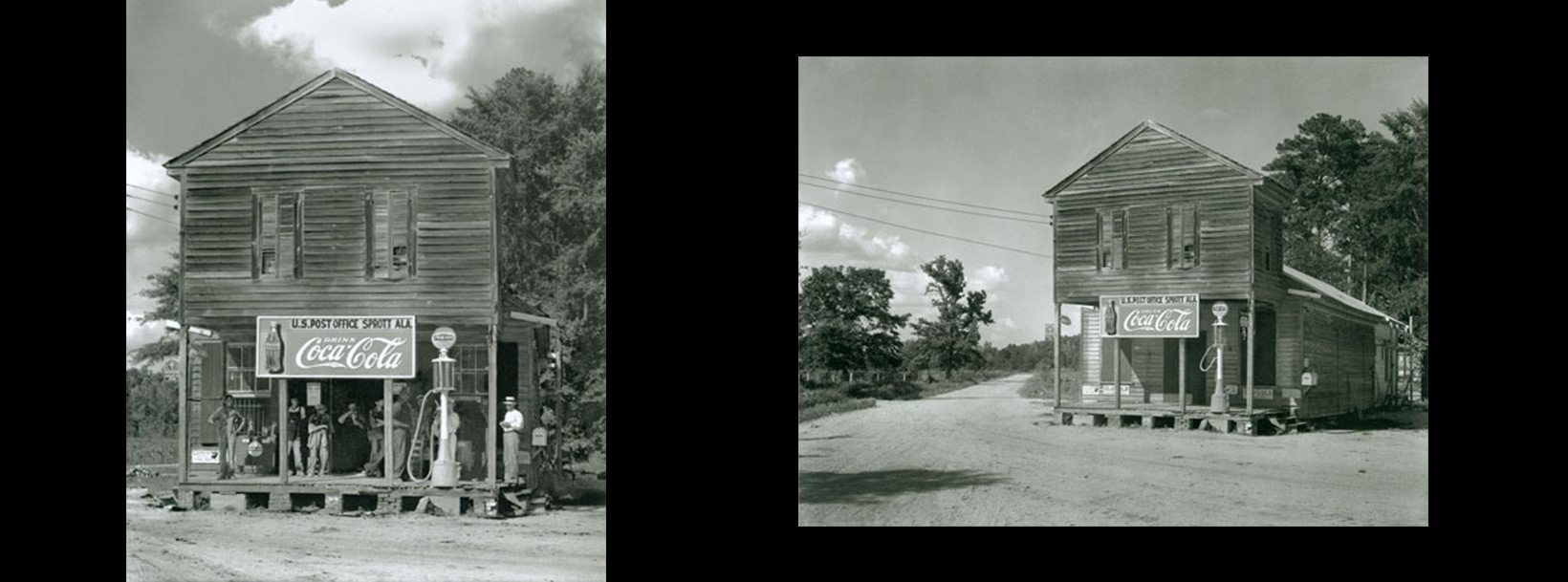

Comparison B

TIME: It is possible to observe the passage of time in some Evans photographs by noting the slight changes in the shadows in successive images. Here, the record of time is seen in the contrast between the views of the building, open for business with a porch full of people in image 1, and tightly shuttered and deserted in image 2. Evans suggests two different interpretations of the same building as he observed it over the course of the day, or perhaps on different days of the week. A single building can appear to be a bustling hub of activity or an abandoned outpost depending upon the crucial element of time.

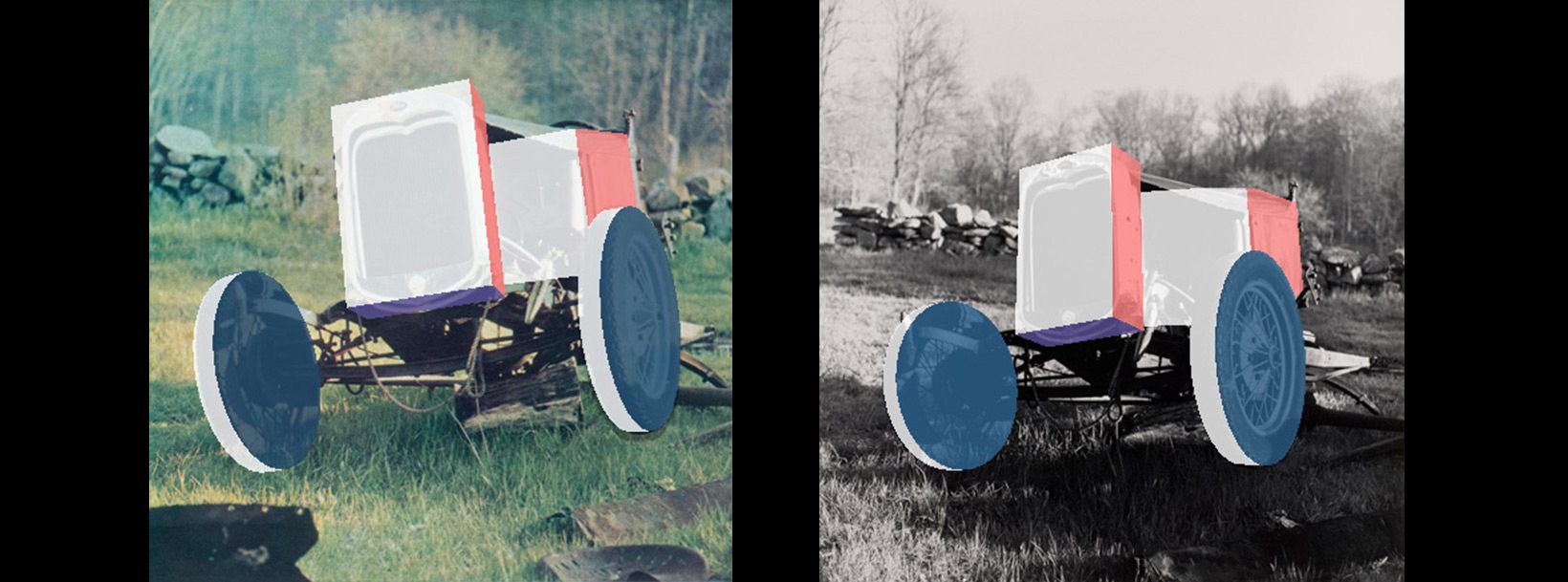

Comparison A

FILM: Shooting photos for his 1962 Fortune magazine portfolio on auto junkyards, Evans loaded two Rolleiflex cameras, one with color film and one with black and white. Along with his usual technical and artistic experiments, he explored color imagery. The automotive debris rusting in the foreground catches our attention in color, but virtually disappears in the shadow in black and white. In image 2 the car’s undercarriage is a tangle of black shapes, while the color of image 1 helps to distinguish the various parts. Even ten years later when asked about color photography Evans disapproved, “I don’t think color is true yet.”

Comparison B

ANGLE: Although the angle is only slightly different in these two images, the Model A is seen from a more head-on view in the color image. The yawning “mouth” of the grill seems to stretch up and away in the black and white version, emphasizing its broken down quality as the chassis seems to sag and collapse.

Essays

No sooner is the phrase “The Great Depression” spoken than a flurry of photographic dramas leaps to mind.

For some the image is Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, while for others it is Arthur Rothstein’s Fleeing a Dust Storm, and for many more the iconic shot is Walker Evans’ Alabama Cotton Tenant Farmer’s Wife. Like Lange and Rothstein, Evans ranks among the Farm Security Administration’s corps of documentary photographers who collectively captured those images of poverty and hard times indelibly etched in American memory. Evans’ contribution to this incredible body of work spanned the brief period from 1935 through 1937, but in those few years he accomplished a lifetime’s work.

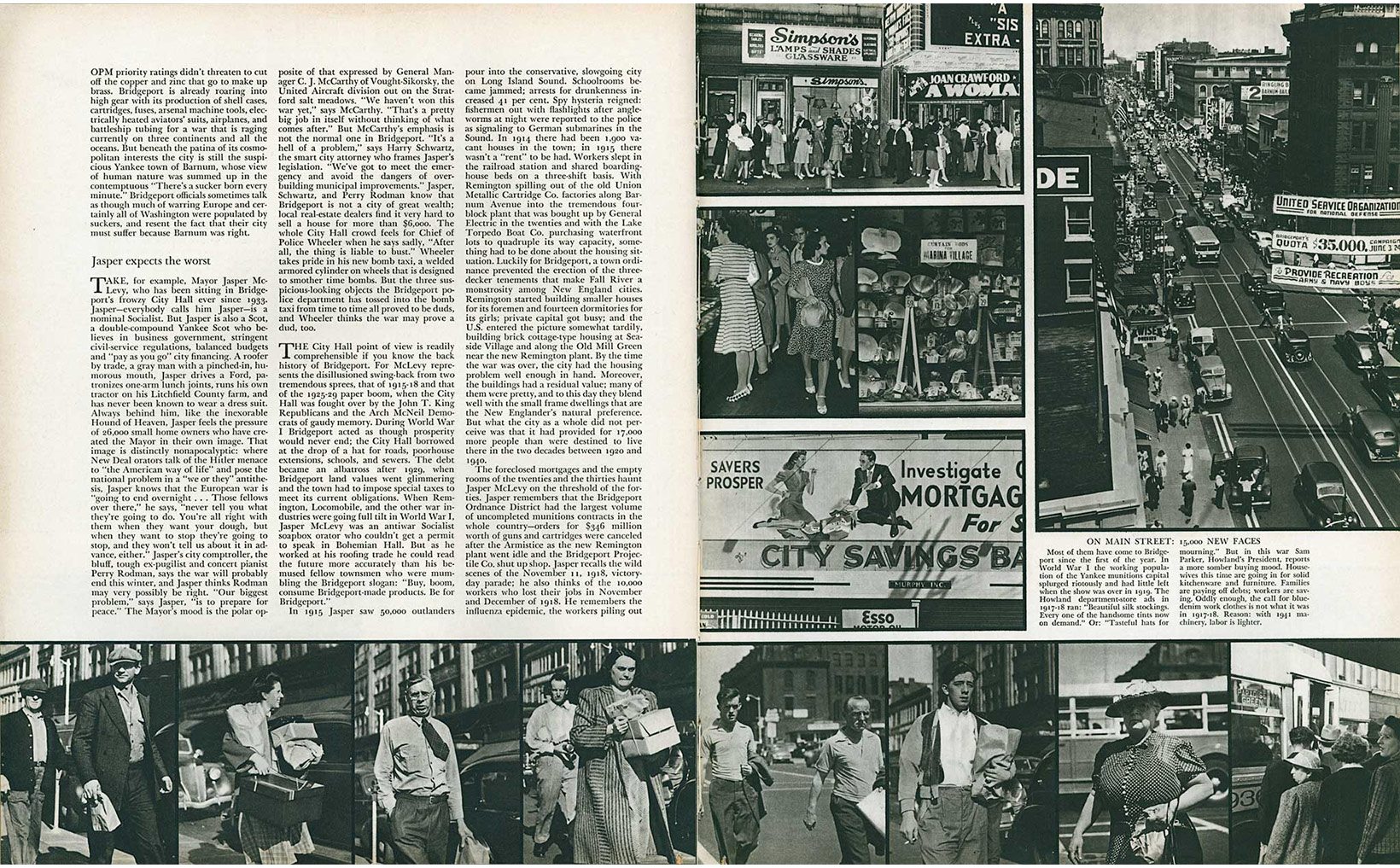

While Evans’ unforgettable Depression-era photographs launched his career and earned him a lasting place in American social and cultural history, the photographs he made during the ensuing years have been largely overlooked. In his later career, a period when he made his home in Lyme, Connecticut, Evans worked for Fortune magazine, published many books, and taught at Yale University, in addition to managing the legacy of his renowned FSA-era photographs. Evans lived through numerous innovations in photography beginning his work with the large format 8×10 camera and moving on to hand-held Rolleiflex and 35mm devices; he guardedly adapted to color film in the 1950s, and eventually came to embrace the instant prints of a Polaroid camera in the 1970s.

Evans made his first trip to Lyme, Connecticut, in 1939, immediately on the heels of his major exhibition and book Walker Evans: American Photographs, the Museum of Modern Art’s first exhibition of an individual photographer and a show that drew heavily on the FSA material. Visiting artist friends in Lyme, Evans spent increasingly more time in the area, lengthening his stays and even taking over a small shack on his friends’ property, which he eventually converted into a makeshift summer home. In the Connecticut countryside he often found inspiration for his Fortune portfolios, from the state’s characteristic stone walls to the auto junkyard quite literally in Evans’ own backyard.

Essays

In the 1960s, he turned his attention to publishing books and other long-term projects including a second edition of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (originally published in 1941)

the landmark collaboration between Evans and James Agee that told the story of three sharecropping families living in rural Hale County, Alabama, in 1936.

Evans’ first self-assigned project following the FSA years culminated in the 1966 publication Many Are Called, a book based on a series of unposed portraits taken in the New York subway in the late 1930s and early 1940s. In the same year the book was published, the Museum of Modern Art exhibited images from the project, which Evans had guided through an evolution of forms and phases in the intervening years.

In the mid-1960s, Evans joined the faculty in Graphic Design at Yale University. In this period, Evans built a large contemporary home in the hills of Lyme, where he often hosted his Yale students as they mingled with a generation of more established artists in area. Never particularly enamored of working in the darkroom, Evans found a number of skilled students and colleagues in the Yale community who would painstakingly print his negatives, including the FSA work, meeting the photographer’s exacting standards.

Following up the Museum of Modern Art’s retrospective of Evans’ career earlier in the year, Yale University Art Gallery held its own tribute to the photographer in December 1971, entitled Walker Evans: Forty Years. The Yale exhibition was the first to feature Evans’ recent passion: collecting. Evans displayed a selection of signs—and photographs of signs—from his growing collection of what many would see as unremarkable, common things. Long intrigued by signs and advertising, Evans made them the subjects of many photographic studies over the years. In a text accompanying the exhibition he compared photography (the taking of images) to collecting (the taking of objects) and, through the juxtaposition of signs and photos of signs in the gallery, semiotically blurred the boundary between the object itself and its surrogate image.

In a final, and widely unknown, photographic campaign, Evans adopted the Polaroid SX-70, a pocket-sized, mass-market camera that produced instant, self-developing prints.

In what historian Alan Trachtenberg has called “the late miracle of his Polaroids,” Evans’ photographic practice was reinvigorated.

Although he first regarded the camera as a toy, he set about to do “something serious” with it as a professional photographer. In an interview he cautioned, “I feel that nobody should touch a Polaroid until he’s over sixty. You should do all that work first.” Between Evans’ initial encounter with the camera in September 1973 and his last photographs in November 1974 he produced over 2,500 Polaroid prints.

Not adverse to new technologies, Evans would likely relish the new light being shed on his FSA photographs, which are today benefitting from digital innovations. High resolution scanning and printing, as well as the development of photo-quality inkjet papers, allow the production of new prints, based on Evans’ negatives, that rival traditional gelatin silver prints. Made by photographer John T. Hill, the former executor of the Estate of Walker Evans and co-curator of the exhibition, archival pigment prints of the FSA material both preserve the images for future generations and enhance our experience of them. Advances in printing permit enlargements of the images that reveal the wealth of detailed information recorded in Evans’ original glass plate negatives, now in the collection the Library of Congress. In an age of increasing economic anxiety, prints such as Alabama Cotton Tenant Farmer’s Wife transcend their historical context and are revitalized in the eyes and minds of contemporary audiences.