Exhibitions

Life Stories in Art: Three American Women Artists in Connecticut

- The Museum will be closed Sunday, April 9 in observance of Easter.

October 3, 2014 – January 25, 2015

Three Women/Three Artists/Three Centuries

Together, these exhibitions highlight the contributions of three important women artists in Connecticut in three different media over the course of three centuries. The Museum’s Krieble Gallery will feature more than 70 works by 19th century painter Mary Rogers Williams; 20th century sculptor Mary Knollenberg; and contemporary glass artist Kari Russell-Pool. Although separate exhibitions, they each carry the theme “Life Stories in Art” and serve as an exploration of these women’s individual journeys of sacrifice, self-discovery, and balancing multiple roles in the pursuit of their art.

Life Stories in Art presents the perfect opportunity to assess the extraordinary role that women have played in American art, both historically and currently,” says Jeffrey Andersen, director. “Each of these artists—although separated by centuries and by different circumstances—demonstrate great courage in their commitment to their art. I hope our audience will be prompted to delve deeply into their individual accomplishments and reconsider their contributions to the arts of Connecticut.”

Exhibition Booklet

Download exhibition booklet for more in-depth information on each artist.

Download BookletThe Art of Mary Rogers Williams

“Forever Seeing New Beauties”

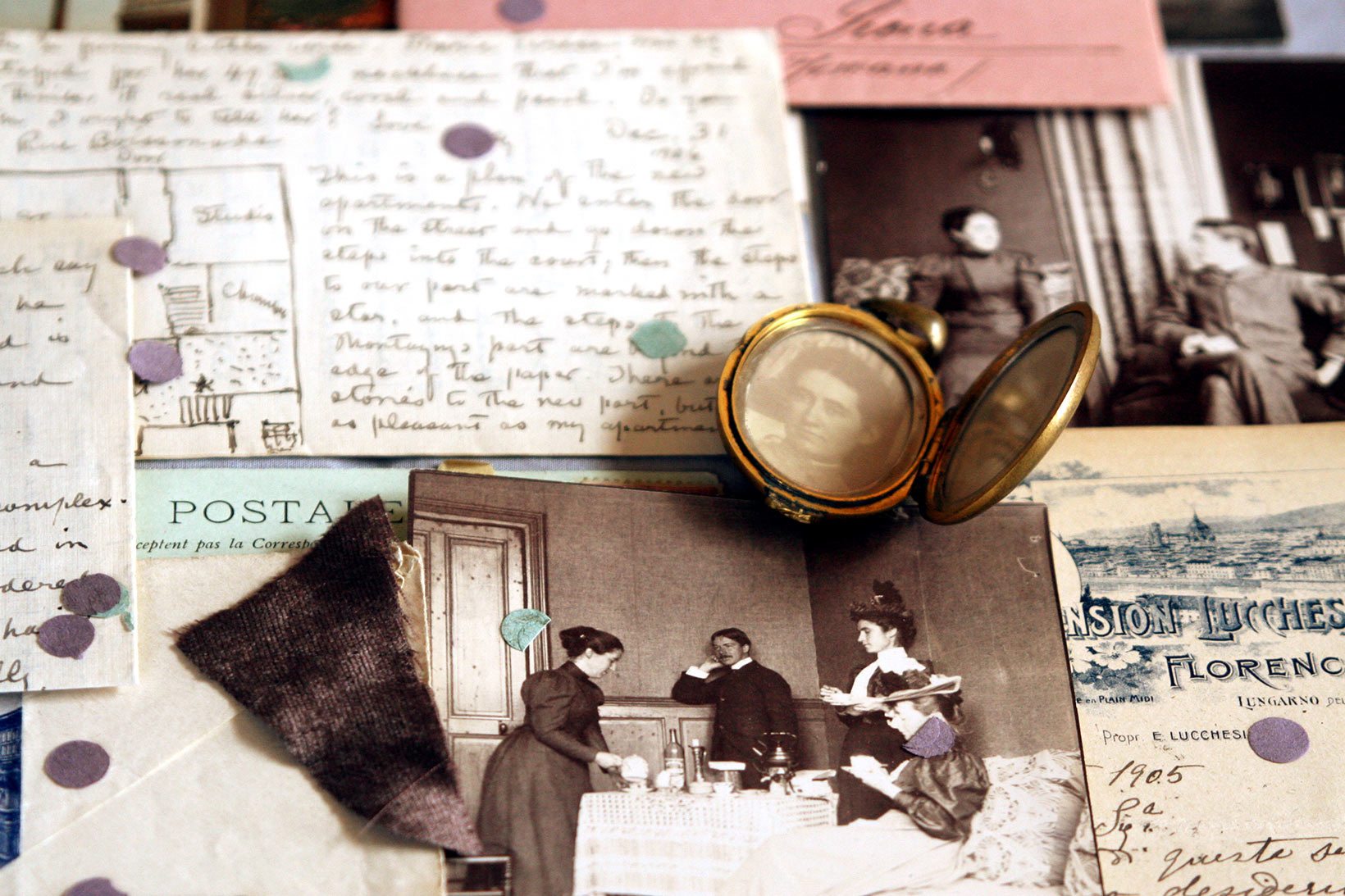

This is the first retrospective of Mary Rogers Williams (1857-1907). Despite an active career as a painter, pastellist, portraitist, and teacher, Williams faced the challenge of acceptance in an art world that was largely closed to women at the time. Her artistic contributions would have descended into obscurity if not for a few supporters who believed in her work and made an effort to preserve it after her unexpected death at the age of fifty. Mary’s sisters kept around 70 works and almost all of her letters, which were entrusted to her good friend and fellow artist, Henry C. White. Henry’s grandson, the artist Nelson Holbrook White, has inherited the collection and is having Mary’s paintings restored gradually. Thanks to the White family’s stewardship, this retrospective recovers and examines her contributions to the American Tonalist movement, unusual in the fact that she was one of the only women to be identified with this style.

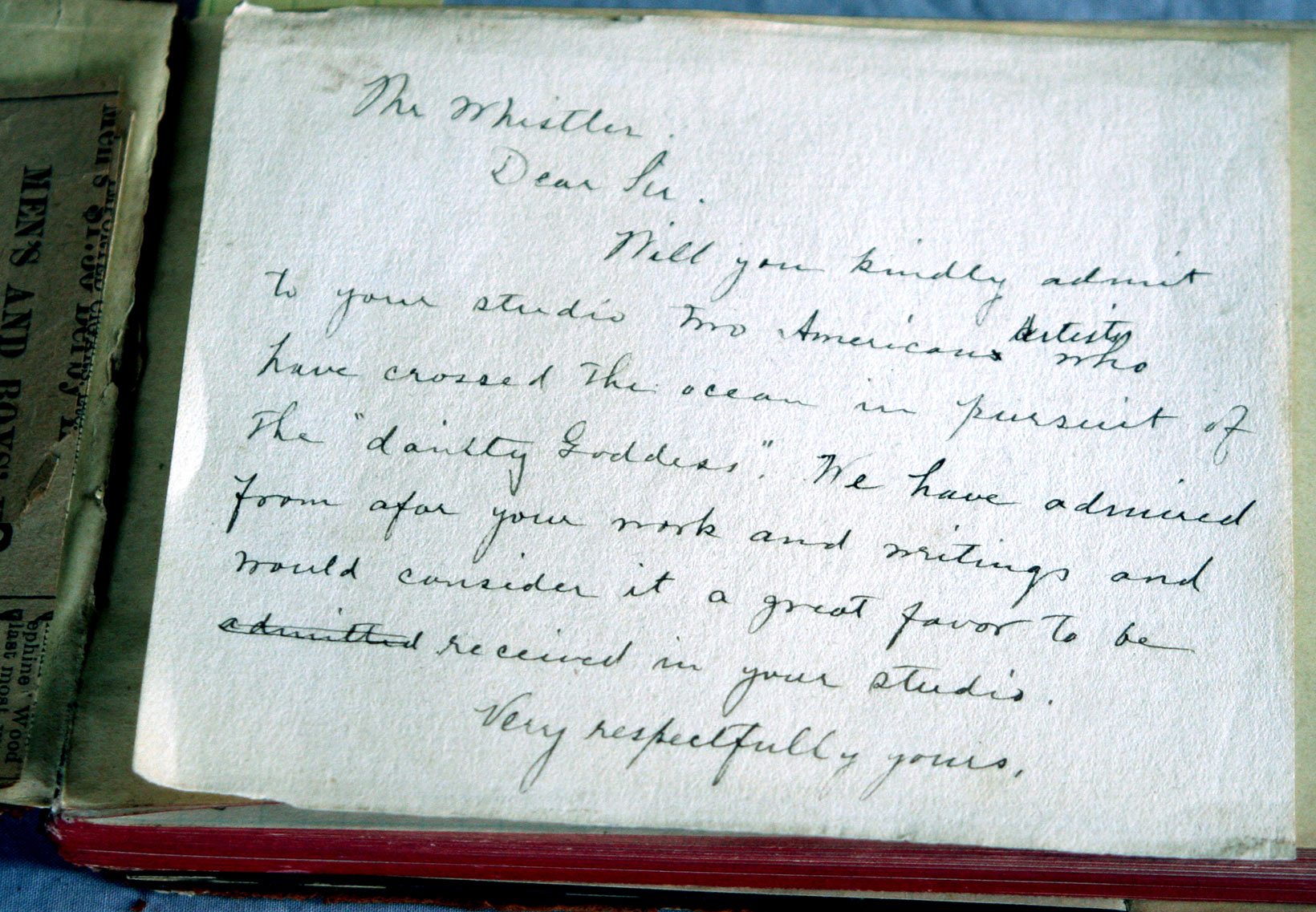

Williams, born and trained in Hartford, became second in command of the art department at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, serving under the landscape painter Dwight Tryon. Unlike many women of the time, Mary’s adventurous spirit would not be bound. During her summers off from teaching, Mary traveled extensively by herself, visiting Norway, Italy, and England. In Europe, she sought out leading artists such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler, learning from him the power of gently evocative landscapes.

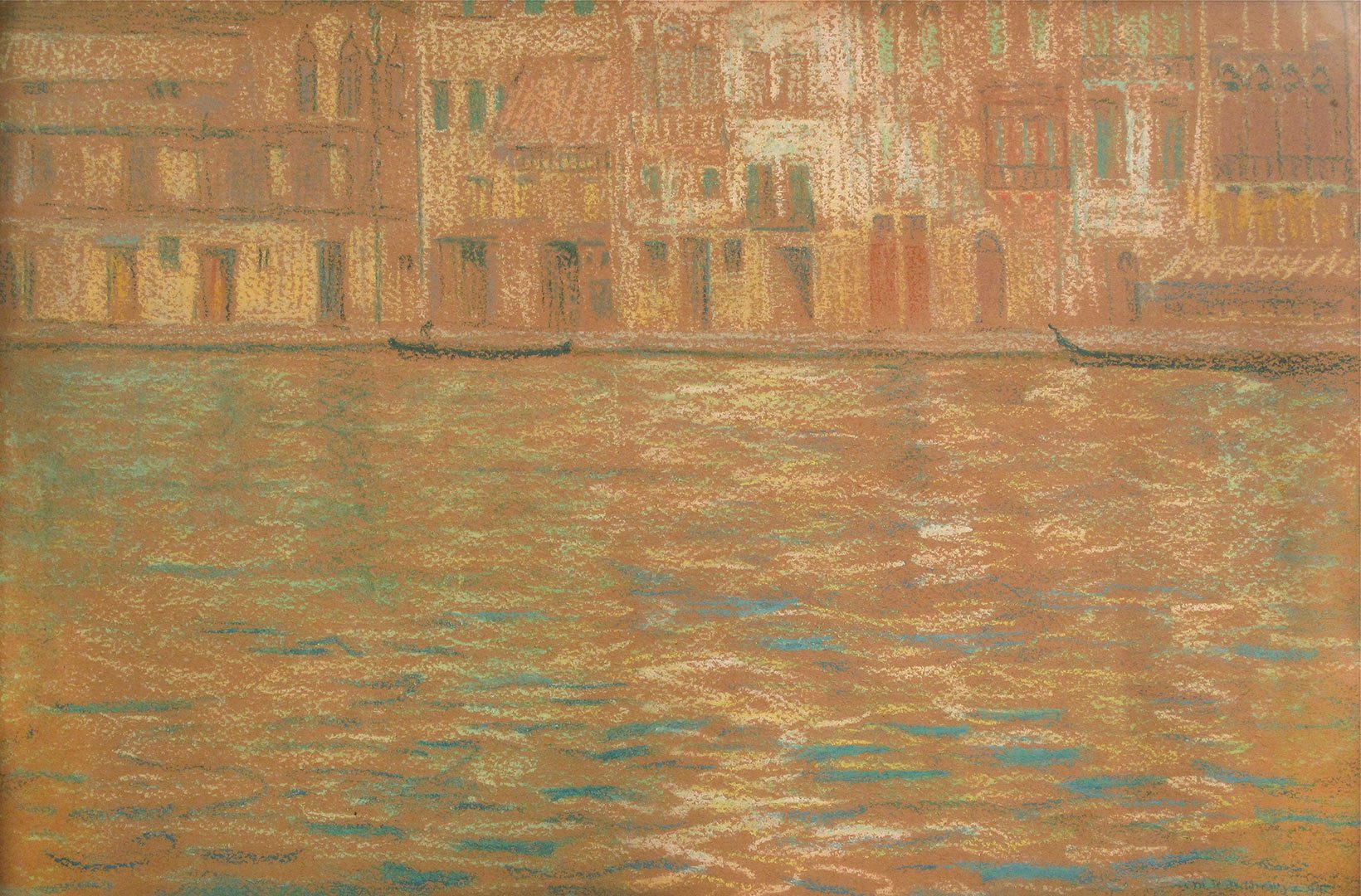

Back in New England, Williams translated these lessons to her students and exemplified them in the works she exhibited at venues such as the American Watercolor Society, the National Academy of Design, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In an untitled pastel of Venice, Williams lends a dream-like quality to a view of buildings glimpsed across the water. Noting her flair for atmospheric effects, The New York Times described her pastels as “curious in their shadowy quality.”

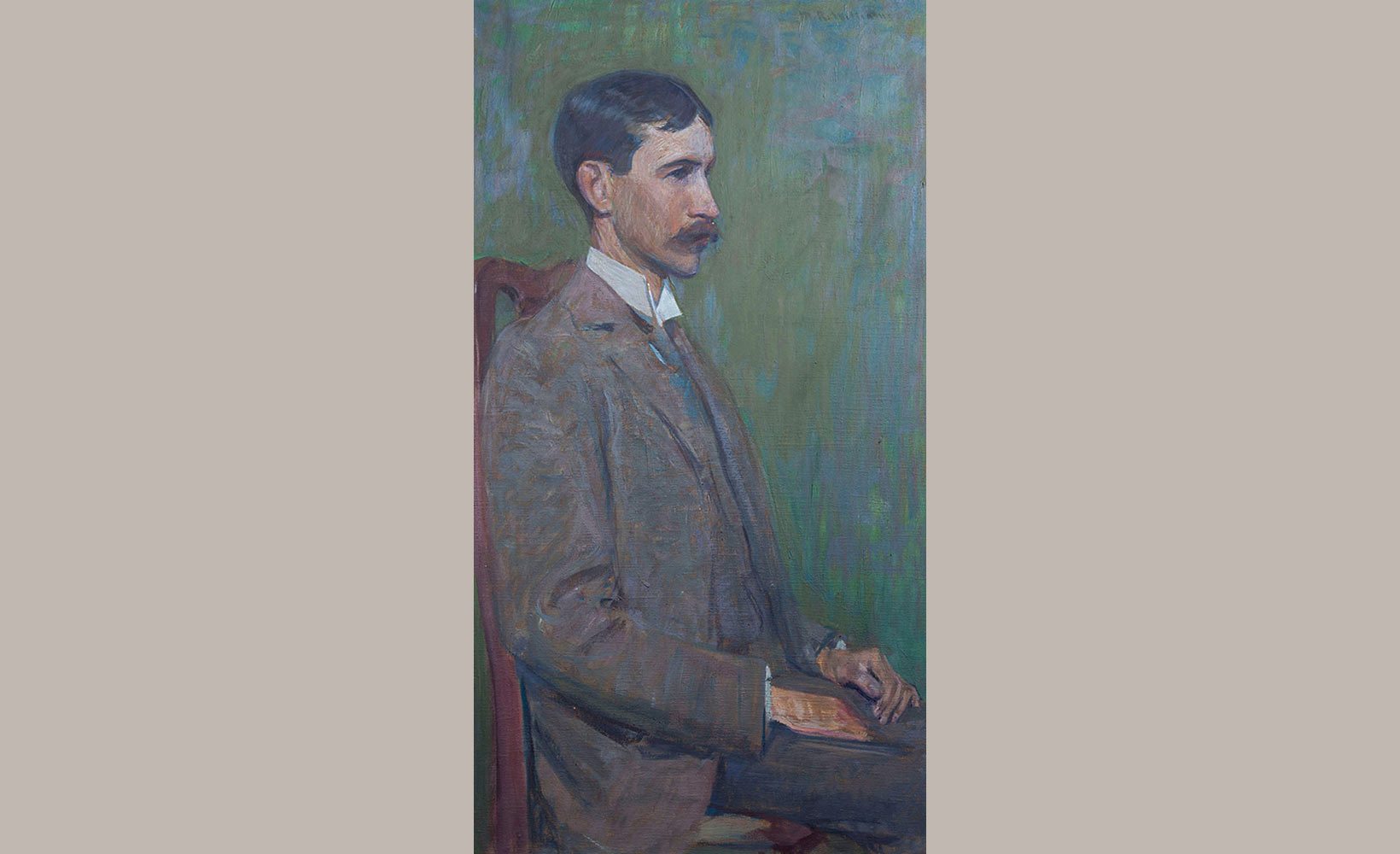

At the same time, Williams excelled at portraiture, depicting Connecticut notables such as the antiquarian George Dudley Seymour and friends, including fellow artist and Lyme Art Colony member Henry C. White, who would play a crucial role in preserving her work. Williams’ portraits incisively capture the spirit of her sitters and blend it with a stylistic sensibility of attenuated forms, strong contours, and unexpected colors. Her portrait of White depicts him as lanky, his frame folded into a chair that accentuates his slender build. Williams flecks color across the portrait’s surface, playing secondary hues off the harmony of the earthy tones in the sitter’s clothes, chair, and background.

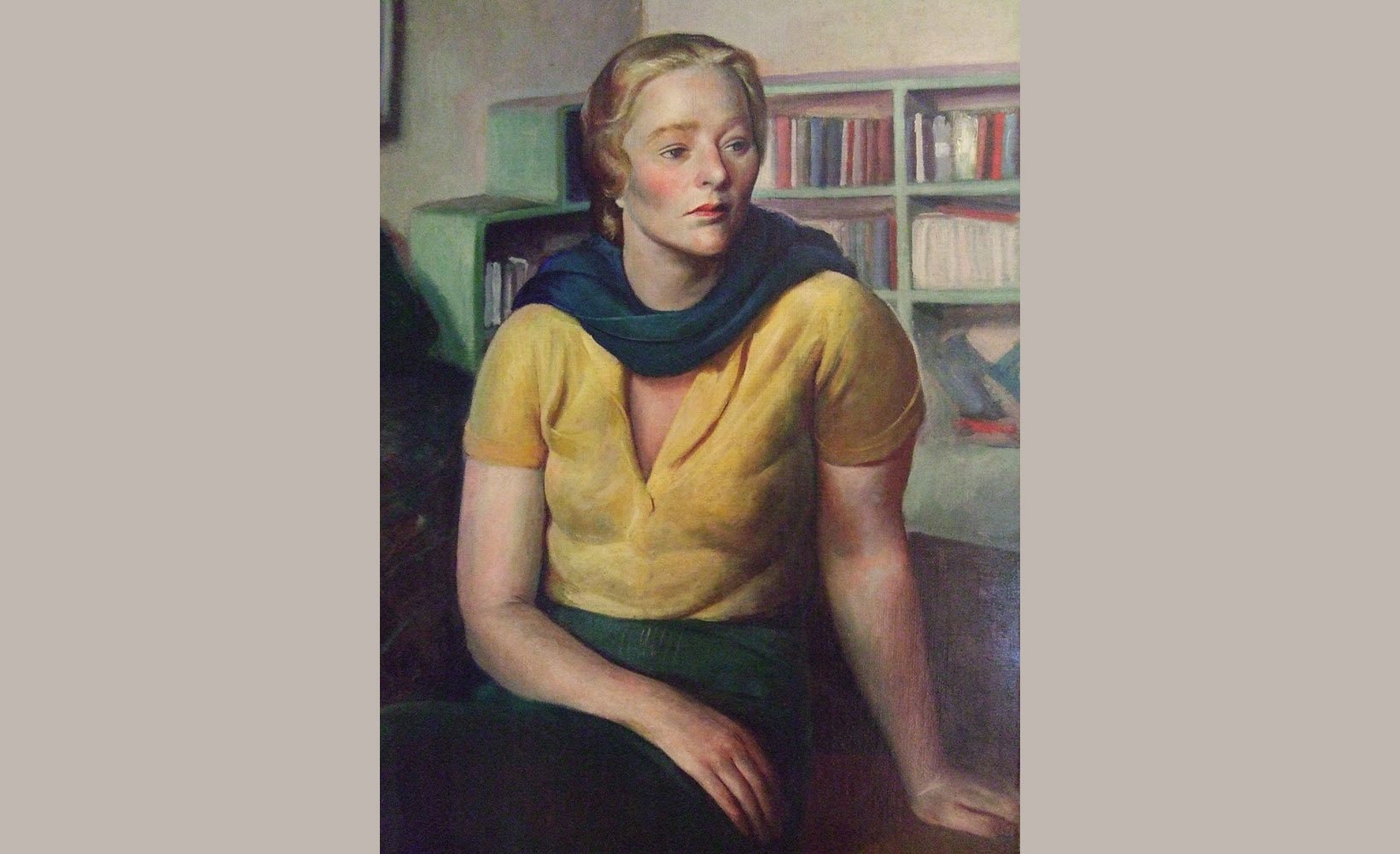

Mary Knollenberg Sculptures

Modern Figures

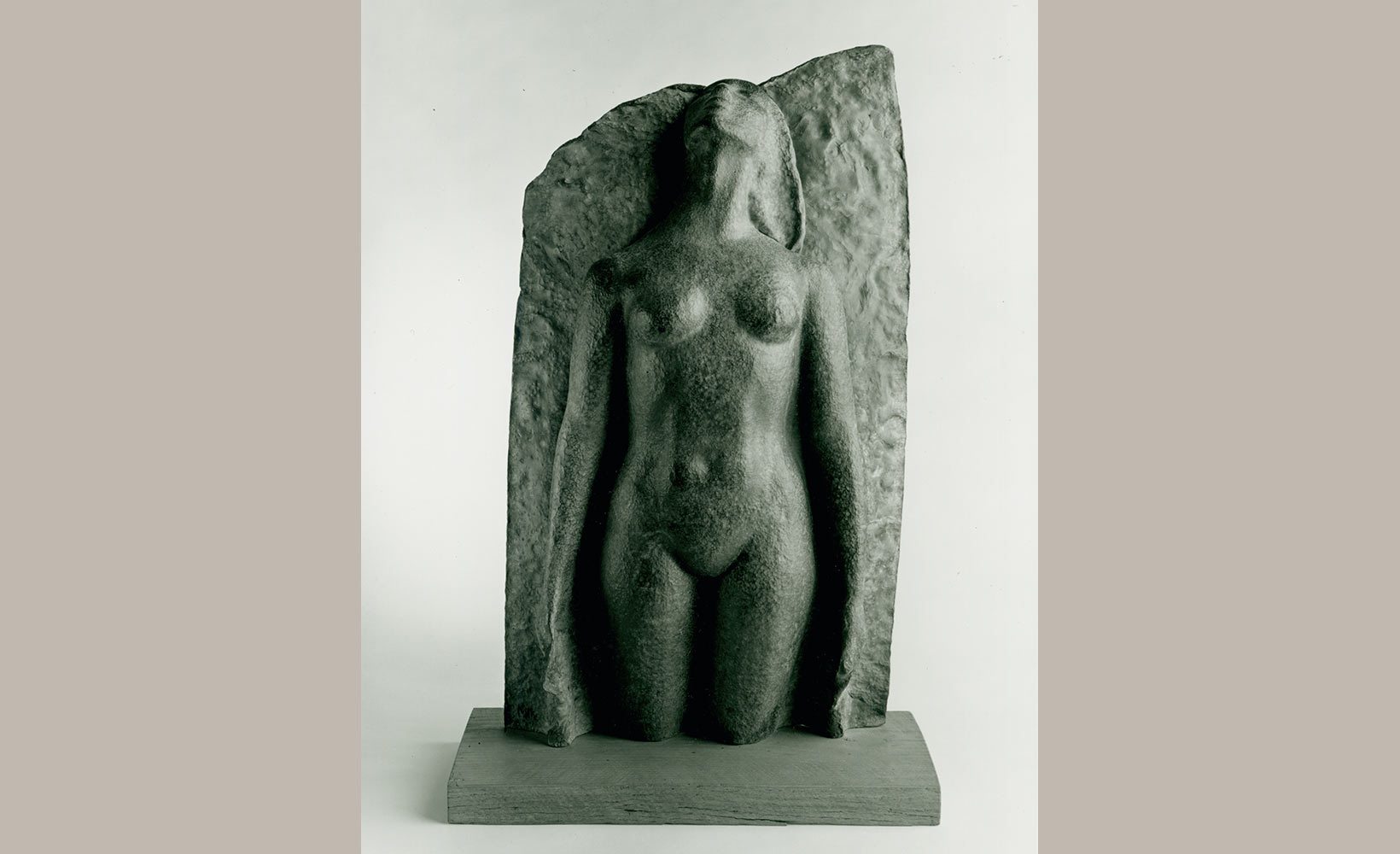

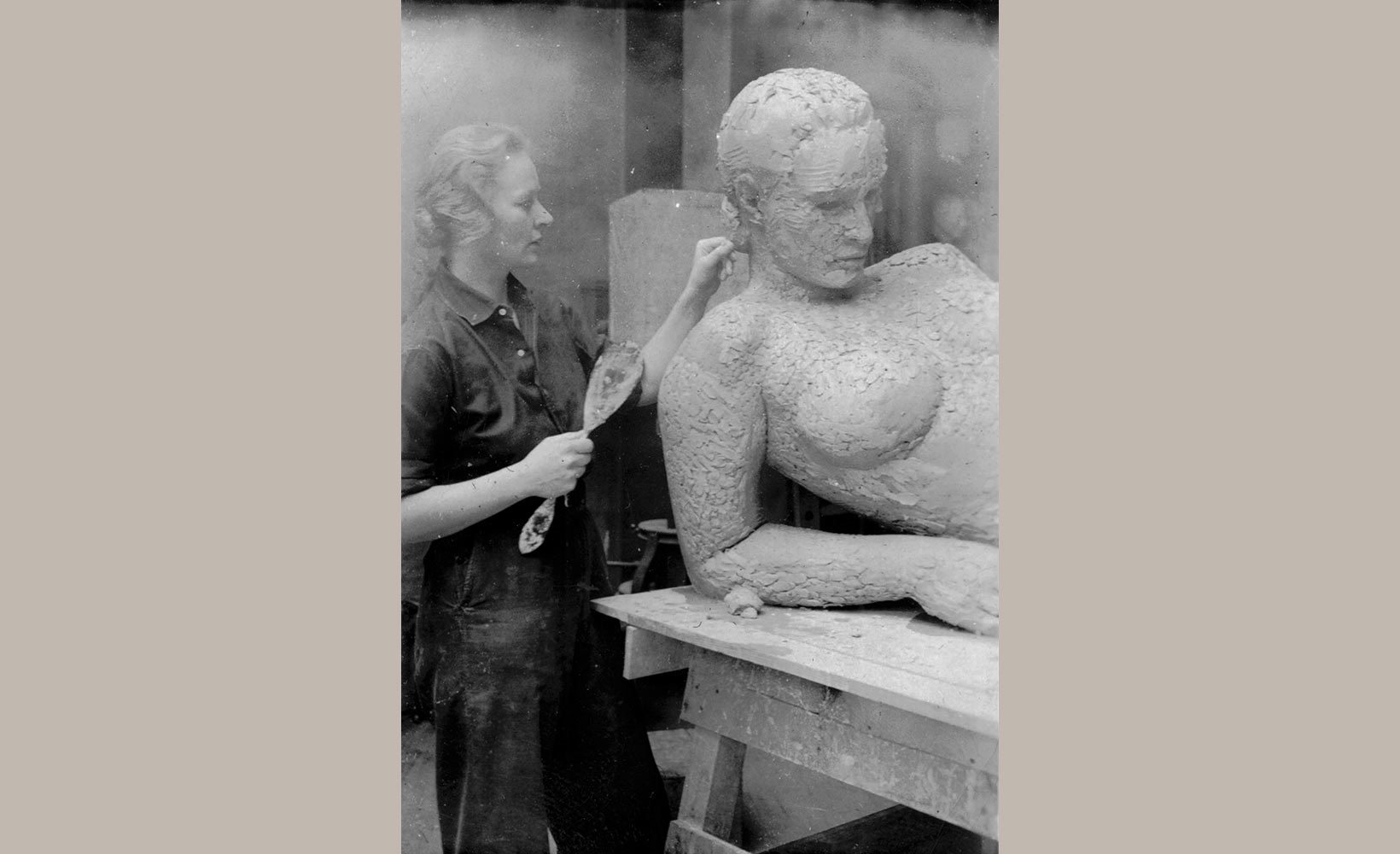

This exhibit of 20 sculptures in bronze, stone, and plaster is the first retrospective since her death in 1992 in Chester, CT. Born in 1904 in New York, Knollenberg trained with sculptors Mahonri Young and Heinz Warnecke. Many of her critically-praised sculptures explore the form of stylized female bodies and the selection of motifs reflects the artist’s lifelong struggle to define herself as a woman. In a 1988 interview, Knollenberg revealed she grew up as a tomboy and as a result, “I didn’t know how to get along with little girls. I didn’t know what little girls were about, and I’ve always had this feeling I didn’t know what it meant to be a woman, what women looked like, or what they were, and I think a part of this doing a woman’s figure is a way of educating myself — a search for identity.”

Josephine, a small statue modeled in 1935 after the artist’s cleaning woman and cast in bronze in 1938, attests to Knollenberg’s appreciation for the strength of the female form. Josephine’s crossed arms and legs and voluptuous proportions convey the sitter’s physical confidence, a quality Knollenberg imparted to many of her depictions of women’s bodies and explored through her own study of dance.

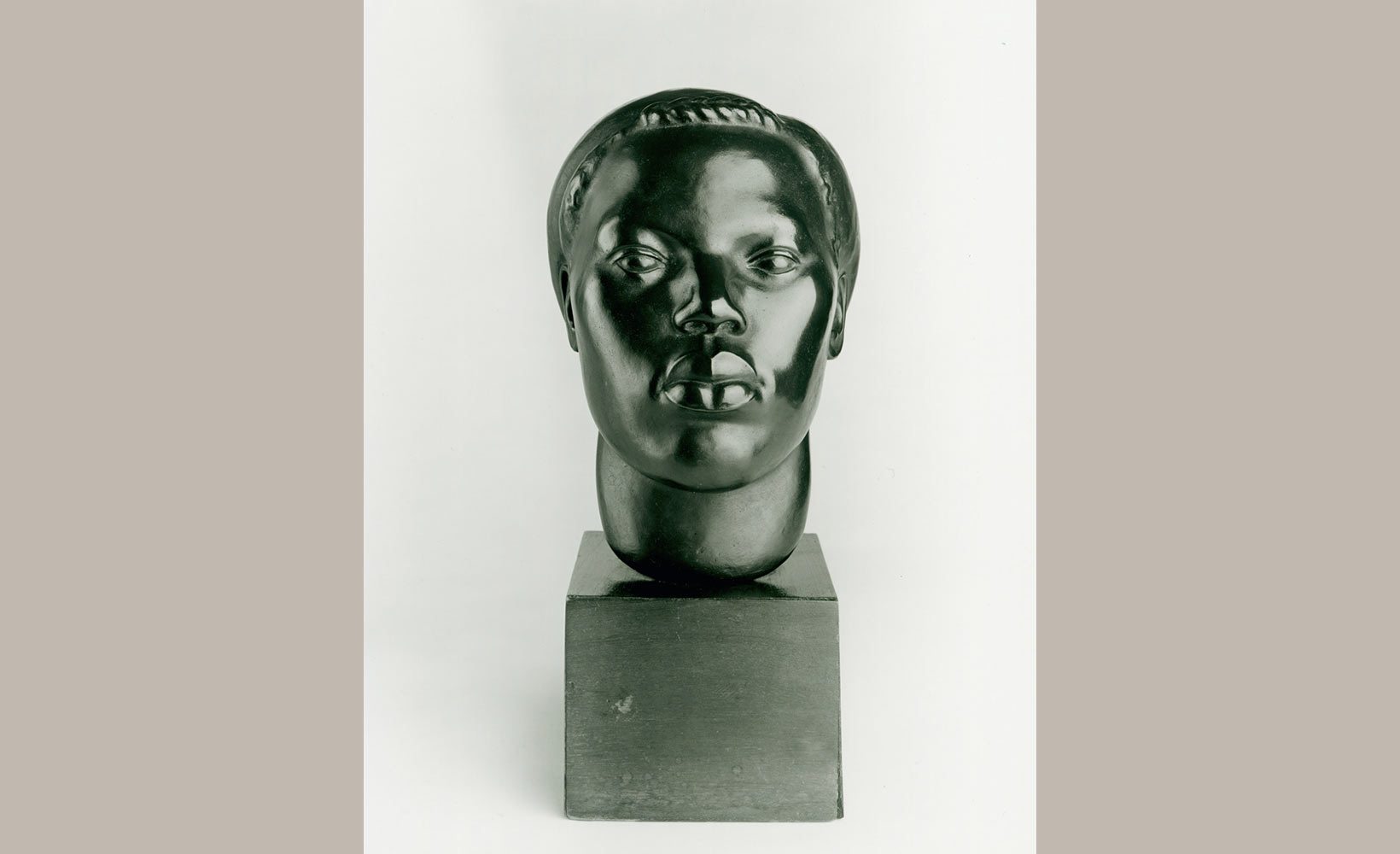

Portrait of Lincoln Kirstein (modeled 1943-44, carved 1945-49), a likeness of the founder of the New York City Ballet, reflects Knollenberg’s embrace of stone carving, a physical demanding medium not traditionally identified with women artists. Knollenberg imparts a graceful arc to the gray marble while also conjuring Kirstein’s creative intensity.

Many creative people were drawn to Knollenberg and she befriended artists, authors, and cultural leaders during her lifetime including Gaston Lachaise, Louis Bromfield, and Lincoln Kirstein. She and her husband, the American historian and Yale University Librarian Bernhard Knollenberg, lived in Chester, CT, from the late 1940s on. It was there that Mary Knollenberg became friends with a circle of artists that included the painter Sewell Sillman and the photographer Walker Evans, subjects of recent exhibitions at the Museum.

Knollenberg’s oeuvre is a small but choice example of mid-twentieth century sculpture and a testament to her role in transforming sculpture from a physical man’s game oriented toward public monuments into a means for women artists to explore their own vital questions. In this way, but without personal fanfare, Knollenberg made a significant contribution to American art.

Self-Portraits in Glass

Kari Russell-Pool

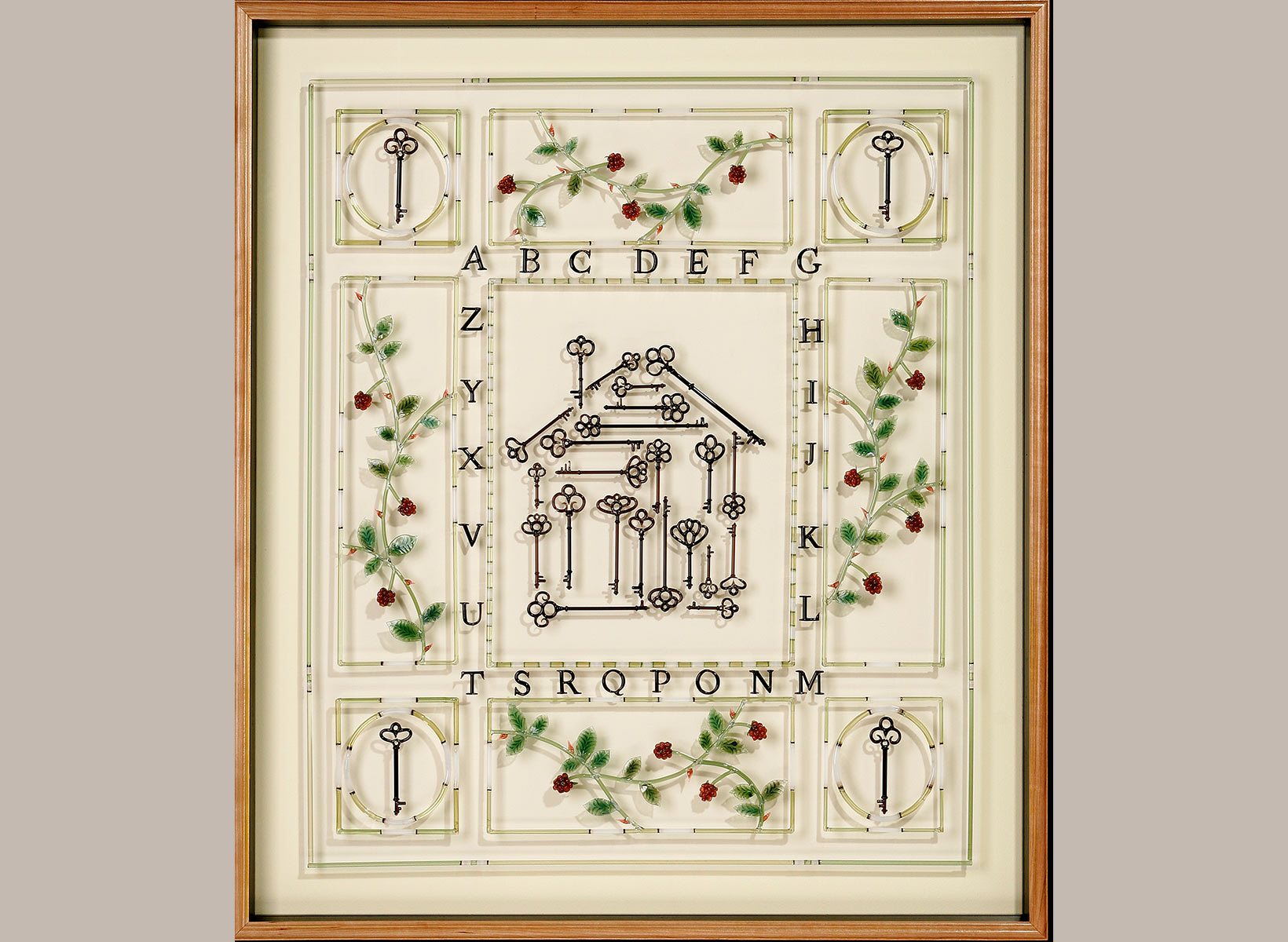

From her Essex, Connecticut, studio Kari Russell-Pool bends, molds, and fuses delicate rods of glass into extremely intricate sculptures. This exhibition highlights her introspective practice of mining both historic forms and daily life to explore the modern world in her art. Alongside a selection of 20 works resembling Greek amphoras, Victorian teapots, needlework samplers, birdcages, and sailor’s valentines, this exhibition debuts one of her first large-scale installations.

Born in 1967 and a graduate of the Cleveland Institute of Art, Russell-Pool uses the glass technique of flameworking, molding, melting, and manipulating small pieces of glass with a single, intense flame to build a large sculpture. With careful experimentation and exploration Russell-Pool has brought a fresh energy to that centuries-old practice by filling heirloom- inspired compositions with contemporary relevance. Every element of this process—from the mixing of colors to the hours of work over a torch flame—allows the artist a painterly level of control over her medium.

Using high heats and temperamental rods of glass, her virtuosic technique gives her pieces a delicate, tactile quality as she grapples with personal ideas.Her work interweaves historic forms and everyday objects with complex ideas to represent the different facets of her life as an artist, mother, thinker, wife, and daughter.

A work such as Homeland, 2006 self-consciously adopts compositions from historic American needlework samplers and story telling quilts, and uses them to highlight the vivid contradictions of the locks, weapons, and stories we use to create an impression of safety and security for our families during times of conflict.

Self Portraits in Glass will also introduce one of the artist’s first large-scale installations. “Kari Russell-Pool works in series, exploring a single motif in great depth through repetition and subtle evolution,” notes Florence Griswold Museum assistant curator Ben Colman. “Her recent series of glass cages began on a small scale, but the exhibit includes a never before seen life-sized installation. I’m thrilled to invite visitors to experience the beauty and intricacy of this new direction in her work.” Taken together, the pieces in the exhibition highlight Kari Russell-Pool’s introspective practice of looking at her own life and experiences to explore the modern world.