- The Museum will be closed Sunday, April 9 in observance of Easter.

SEE/Change: Seven Miles to Farmington

How Paintings are Made

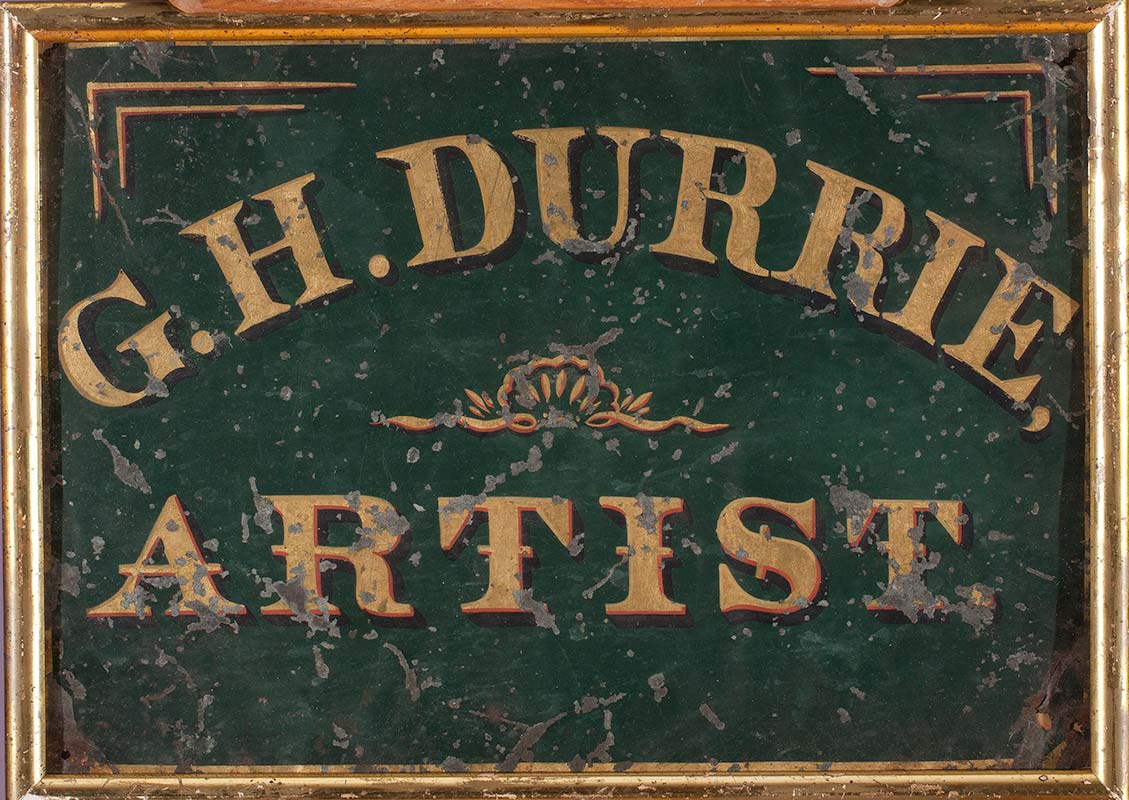

George Henry Durrie lived in the industrial era, therefore his paintings incorporate manufactured materials such as pre-mixed paint, primers, mediums, and varnishes that artists could buy rather than make themselves as they had in prior centuries. Although not all of Durries’ paintings have been analyzed by art conservators, those that have show that he used canvases he bought in New York City, from the firm of Raynolds, Devoe, & Pratt. In another instance, he bought canvas from Kelly, another New York supplier, on his way down to Virginia in November 1845.

Preparing the Canvas

Whether purchased in New York or through a local storekeeper in New Haven, Durrie bought the canvas fabric—woven of either cotton or linen—to which sizing and a ground layer had already been applied. Sizing, usually with rabbit-skin glue, coated the fabric to protect it from degradation caused by oil mixed with pigments, ensuring the paint would stick to the canvas. Following sizing, the ground layer, usually an off-white solution of chalk, would fill in any bumps or texture in the canvas.

Grounds created a smooth, durable surface on which to paint could be applied without the colors—mixed with oil—soaking into the canvas. The tone of the ground layer affects the appearance of colors layered on top, so artists thought carefully about even the parts of their paintings that would remain below the surface. In Seven Miles to Farmington, the ground layer appears to be pinkish-tan, perhaps to add depth to the many areas of white snow.

Stretching the Canvas

A good, supple ground layer was also crucial for artists like Durrie, who traveled. If properly prepared, these canvases could be rolled after painting for storage or shipment without damaging the picture. To create a taut surface for painting, canvas would be pulled around wooden bars called “stretchers” that were joined at the corners to form a square or rectangle, and then nailed to the edges.

When traveling in the South in 1846, Durrie recorded in his journal for April 30 receiving delivery of a box with six canvases, without stretchers. He may have ordered the exact number needed for pending commissions, or if he obtained a new commission, he could stretch an additional canvas from his supply. Otherwise, he presumably kept them unstretched for portability.

The Paint

Just as artists of the 1850s could buy prepared canvases and stretchers, they could also purchase pre-mixed paint in re-sealable metal tubes. This innovation gave paints greater portability, and allowed artists to broaden their palettes beyond a limited range of colors laboriously prepared in small quantities. For centuries, artists had worked with minerals and other natural materials to produce paint pigments. In the 1850s, new synthetic pigments were introduced that offered more intense colors or otherwise exceeded the longevity of natural pigments. It is unclear whether Durrie took advantage of these new paints, which were embraced by Hudson River School painters such as Frederic E. Church. The only mentions of paint in Durrie’s diary come in 1845, when bought a traditional lead white pigment in New Haven, and again when he says that he “bought some color” from the art supply store of Dechaux in New York City on his way to Virginia.

Binding Medium

To paint, artists would combine their pigments with a binding medium such as linseed oil to form a paste that could be spread with a brush. With the invention of machine-ground paint in tubes, some artists didn’t like the more uniform consistency and chose to dilute the paint with turpentine for greater transparency. Depending on the type and amount of oil used, artists could achieve lots of different effects, from thin transparent glazes to thick dabs of pure color that added texture to a surface. Oil paints dry slowly, meaning artists like Durrie could only work on their pictures a certain amount each day before letting them cure slightly overnight. Even with commercially-prepared materials, artists continued to experiment as they had for centuries. Because some of the ingredients and processes were new, these untested combinations could change the appearance and durability of paintings over time by cracking or darkening. In Durrie’s era, finished paintings that had dried sufficiently would receive a coat of varnish to makes the colors more vibrant and to protect the picture’s surface.

Framing the Finished Painting

When a painting was ready for display or sale, artists would frame the picture. An artist might reserve an elaborate frame for a special exhibition, but remove that from the picture before sale. Just as art materials were manufactured through industrial processes by the mid-nineteenth century, frames were also produced that way. While artists had once made or commissioned hand-carved wood frames, by the 1850s, they could buy frames with elaborate plaster decorations molded to resemble wood, then applied in sections to wooden supports and gilded to an attractive shine. Some of this applied plaster ornament might echo the subject of painting, representing vegetables, fruit, flowers, or shells like those depicted in a landscape or still-life composition. Seven Miles to Farmington has lost its original frame, but we do know that Durrie advertised his work for sale sporting frames by Samuel M. Bassett, a looking glass, portrait, and picture frame manufacturer in New Haven.

Selling the Painting

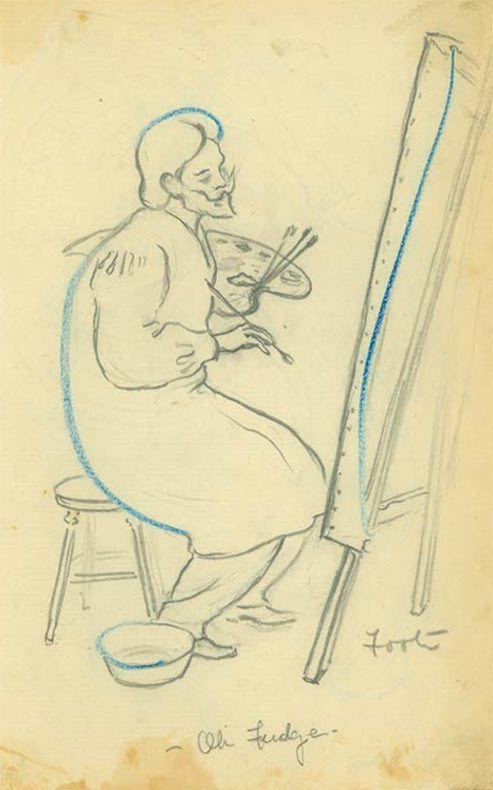

Durrie was also able to take advantage of the broader market for paintings that existed by the 1850s. While he traveled in pursuit of private commissions earlier in his career, his snowy landscape were painted in New Haven for sale through galleries in large cities like New York. The artist’s obituary recalls “We have lingered over these faithful delineations of country life greeting us from the window of our principle art emporiums on Broadway….” Customers could see and buy Durrie’s work at exhibitions or from the emerging category of stores similar to today’s art galleries. During his day, these “emporiums” sold prints and paintings, often along with mirrors and frames. While we don’t know the price paid by the first buyer of Seven Miles to Farmington, another Durrie picture called New England Winter Scene sold for $165 at a public auction of the artist’s work at New York’s Academy of Design in 1859—a significant sum in those days. At other times, Durrie sold his pictures at Durrie & Peck, his family’s stationary, book, and printing shop in New Haven, as well as through raffles tied to temporary exhibitions at fairs or orchestrated as promotions during his trips in search of commissions. Available records for Durrie’s public sales indicate that only his largest works went for prices in the range of $100 or more. Many of the compositions he offered for sale were smaller, and priced more inexpensively. While a customer might commission a large painting, the more casual buyer wanted something to “adorn their parlors,” as an advertisement for a May 1854 sale of Durrie’s work in New Haven encouraged. “Admirers of the fine arts” could rest assured that the “pictures will stand for ages as an evidence of a cultivated and refined taste.”

Have a question or comment regarding SEE/change? Enter your email and comment here.